Thinking Functionally in PHP?

Introduction

That’s right! If you thought that PHP stood for PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor, you’re wrong. It stands for PHunctional Programming… OK I’m only kidding.

The PHP community has come a long way since the early starts of PHP mainly as a procedural, imperative language. Now, since PHP 5 you’ve become a Object-Oriented (OO) developer. You take advantage of abstract classes and interfaces to properly implement the guiding principles of polymorphism, inheritance, and encapsulation. All of this comes into play when building rich domain models utilizing all of the coolest design patterns. Having learned all this, have you been able to reduce the development effort of building large enterprise web applications? Certainly. But is complexity still an issue and bugs frequent? Is your application easy to unit test? How reusable is your code?

The PHP applications of yesterday are no match for the complex, dynamic, and distributed applications of today. It’s commonplace now that our users demand that their applications run in cloud environments, integrated with a network of third-party services, and expect SLAs to hold at above 99%. The new buzzword is microservices architectures. You’ll always be dealing with having to balance low cost with return of investment against our desire to build robust, maintainable architectures.

Naturally, as developers, we gravitate towards MVC frameworks that help us create an extensible and clean system design with scaffolding and plumbing for routing, templates, persistence models, services, dependency injection (DI), and built-in integration with database servers–Laravel is a good example of this and there are many others. Despite all of this, our business logic code is still becoming hard to reason about, and this is because we still use things like shared variables, mutable state, monolithic functions, side effects, and others. These seemingly small concerns, which we secretly know to be bad practices but do them anyways, are what functional programming encourages and challenges you to pay close attention to.

Object-oriented design certainly moves the needle in the right direction, but we need more. Perhaps you’ve been hearing about functional programming (FP) in recent years and how companies like Twitter move to Scala, WhatsApp written in Erlang. Also, language manufacturers are placing functional constructs into their languages. Hence, Java, JavaScript, F#, C#, Scala, Python, Ruby, all have some form of functional features because the industry is realizing that writing code functionally is opening the door to very clean and extensible architectures, as well as making their developers more productive. Companies like Netflix have bet their success on functional-reactive systems, which are built heavily on these ideas, so we’ll look at reactive solutions built only using PHP.

If you don’t know that PHP also supports writing functional code, then you downloaded the right book. FP is the programming paradigm you need. While based on very simple concepts, FP requires a shift in the way you think about a problem. This isn’t a new tool, a library, or an API, but a different approach to problem solving that will become intuitive once you’ve understood its basic principles, design patterns, and how they can be used against the most complex tasks. Also, it’s not an all or nothing solution. In later chapters, I’ll show you how FP can be used in conjunction with OO and unpack the meaning of “OO in the large, FP in the small.”

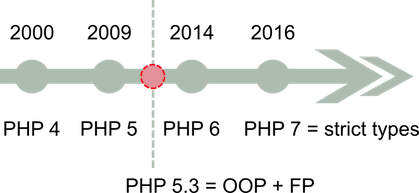

Which PHP version to use?

As I mentioned before, you can implement a functional style using PHP 5.3+. This is around the time that the Closure class was added to the language (more on this later). However, there are good reasons for upgrading to PHP 7. Aside from it being much faster, matching the runtime speed of Hack, and sometimes even better, the latest release adds strict typing and scalar type declarations.

Type declarations allow you to qualify any function parameter with its proper class or scalar type (boolean, integer, string, MyClass, etc). These were partially supported in PHP 5 as “type hints” but without scalar support. In PHP 7, you can also declare the type of a function’s return value.

Being a dynamic language, PHP will always attempt to coerce values of the wrong type into the expected scalar type, if appropriate. For instance, a function that expects an integer argument, when given a string, will coerce that value to an integer:

1 function increment($counter) {

2 return ++$counter;

3 }

4 increment("Ft. Lauderdale"); //-> Ft. Lauderdalf ????

Sometimes we want this flexibility, but when we overdo it this can lead to very confusing and hard to read code. What we’ll do in this book is use PHP’s strict typing mechanism which you can turn on by including this at the top of every file:

1 declare(strict_types=1);

Type declarations makes your code instantly self-documented, allows the compiler to perform certain clever optimizations, and lets modern IDEs better guide you using type inference. Types checks also ensure your code is correct by enforcing type constraints on your function calls. In PHP, a TypeError occurs when a function contract is violated:

1 increment("Ft. Lauderdale");

2

3 PHP Warning: Uncaught TypeError: Argument 1 passed to increment() must be of th\

4 e type integer, string given...

Armed with the proper tool, let’s discuss why learning to think functionally is important and how it can help you combat the complexities of PHP programs.

Hello FP

As I mentioned before, functional programming is not a framework or a tool, but a way of writing code; thinking functionally is radically different from thinking in object-oriented or imperative terms. So, how do you become functional? How do you begin to think this way? Functional programming is actually very intuitive once you’ve grasped its essence. Unlearning old habits is actually the hardest part and can be a huge paradigm shift for most people that come from a different background.

In simple terms, FP is a software development style that places a major emphasis on the use of functions. In this regard, you might consider it a procedural programming paradigm (based on procedures, subroutines, or functions), and at its core it is, but with very different philosophies. You might say, “well, I already use functions on a day-to-day basis at work; what’s the difference?” As I mentioned earlier, functional programming requires you to think a bit differently about how to approach the tasks you are facing. Your goal will be to abstract entire control flows and operations on data with functions in order to avoid side effects and reduce mutation of state in your application. By practicing FP, you’ll become an expert in certain PHP language constructs that are rarely used in other paradigms, like taking advantage of closures and higher-order functions, which were introduced back in PHP 5.3. Both of these concepts are key to building the functional primitives that you’ll be using in your code.

Without further ado, let’s start with a simple ‘Hello FP’ example. Creating a simple script is probably the easiest way to get PHP up and running, and that’s all you’ll need for this chapter. Fire up your PHP REPL [shell> php -a]. Because I want to focus more on building the theoretical foundations in this chapter, I’ll use very simple examples and simple functions. As you move through the book, we’ll tackle on more real-world examples that involve file systems, HTTP requests, databases, etc.

1 $file = fopen('ch01.txt', 'w');

2 fwrite($file, 'Hello FP!'); //-> writes 'Hello FP'

This program is very simple, but because everything is hard-coded you can’t use it to display messages dynamically. Say you wanted to change the message contents or where it will be written to; you will need to rewrite this entire expression. Consider wrapping this code with a function and making these change-points parameters, so that you write it once and use it with any configuration.

1 function toFile($filename, $message) {

2 $file = fopen($filename, 'w');

3 return fwrite($file, $message);

4 }

5

6 toFile('ch01.txt', 'Hello FP'); //-> writes 'Hello FP'

An improvement, indeed, but still not a completely reusable piece of code. Suppose your requirements change and now you need to repeat this message twice. Obviously, your reaction will be to change the business logic of toFile to support this:

1 function toFile($filename, $message) {

2 $file = fopen($filename, 'w');

3 return fwrite($file, $message. ' ' . $message);

4 }

5

6 toFile('ch01.txt', 'Hello FP'); //-> writes 'Hello FP Hello FP'

This simple thought process of creating parameterized functions to carry out simple tasks is a step in the right direction; however, it would be nice to minimize reaching into your core logic to support slight changes in requirements. We need to make our code more extensible. Thinking functionally involves treating parameters as not just simple scalar values but also as functions themselves that provide additional functionality; it also involves using functions or (callables) as just pieces of data that can be passed around anywhere. The end result is that we end up evaluating and combining lots of functions together that individually don’t add much value, but together solve entire programs. I’ll make a slight transformation to the function toFile:

1 function toFile($filename): callable {

2 return function ($message) use ($filename): int {

3 $file = fopen($filename, 'w');

4 return fwrite($file, $message);

5 };

6 }

At first, it won’t be intuitive why I made this change. Returning functions from other functions? Let me fast-forward a bit more and show you how I can use this function in its current form. Here’s a sneak peek at this same program using a functional approach.

1 $run = compose(toFile('ch01.txt'), $repeat(2), 'htmlentities');

2 $run('Functional PHP <i>Rocks!</i>');

3

4 //-> writes 'Functional PHP <i>Rocks!</i>

5 // Functional PHP <i>Rocks!</i>'

And just as I directed this input text to a file, I could have just as easily sent it to the console, to the database, or over the network. Without a doubt, this looks radically different than the original. I’ll highlight just a couple of things now. For starters, the file is not a scalar string anymore; it’s a function or callable called toFile. Also, notice how I was able to split the logic of IO from manipulating its contents. Visually, it feels as though we’re creating a bigger function from smaller ones. In traditional PHP applications, it’s rare to see functions used this way. We typically declare functions and invoke them directly. In FP, it’s common to pass around function references.

Above all, the important aspect about this code sample above is that it captures the process of decomposing a program into smaller pieces that are more reusable, reliable, and easier to understand; then they are combined to form an entire program that is easier to reason about as a whole. Thinking about each of these simple functions individually is very easy, and separating the concerns of business logic and file IO makes your programs easier to test. Every functional program follows this fundamental principle.

Now I just introduced a new concept compose, itself a function, to invoke a series of other functions together. I’ll explain what this means later on and how to use it to its fullest potential. Behind the scenes, it basically links each function in a chain-like manner by passing the return value of one as input to the next. In this case, the string “Functional PHP <i>Rocks!</i>” was passed into htmlentities which returns an HTML-escaped string, passed into $repeat(2), and finally its result passed into toFile. All you need to is make sure every function individually executes correctly. Because PHP 7 ensures that all of the types match, you can be confident this program will yield the right results. This is analogous to stacking legos together and will be central to the theme in this book: “The Art of Function Composition.”

So, why does functional code look this way? I like to think of it as basically parameterizing your code so that you can easily change it in a non-invasive manner—like adjusting an algorithm’s initial conditions. This visual quality is not accidental. When comparing the functional to the non-functional solution, you may have noticed that there is a radical difference in style. Both achieve the same purpose, yet look very different. This is due to functional programming’s inherent declarative style of development.

Declarative coding

Functional programming is foremost a declarative programming paradigm. This means they express a logical connection of operations without revealing how they’re implemented or how data actually flows through them. Chapter 3 shows you how to build these data flows using point-free coding.

As you know, the more popular models used today in PHP are procedural and object-oriented, both imperative paradigms. For instance, sites built using older versions of Wordpress or Moodle are heavily procedural; whereas, sites built using Laravel are completely OOP.

Imperative programming treats a computer program as merely a sequence of top-to-bottom statements that change the state of the system in order to compute a result. Let’s take a look at a simple imperative example. Suppose you need to square all of the numbers in an array. An imperative program follows these steps:

1 $array = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9];

2

3 for($i = 0; $i < count($array); $i++) {

4 $array[$i] = pow($array[$i], 2);

5 }

6

7 $array; //-> [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81]

Imperative programming tells the computer, in great detail, how to perform a certain task (looping through and applying the square formula to each number, in this case). This is the most common way of writing this code and most likely will be your first approach to tackling this problem.

Declarative programming, on the other hand, separates program description from evaluation. It focuses on the use of expressions to describe what the logic of a program is or what output would look like without necessarily specifying its control flow or state changes. Familiar examples of declarative code are seen in SQL statements:

1 SELECT * FROM Person

2 WHERE age > 60

3 ORDER BY age DESC;

Also, Regular Expressions. The following expression extracts the host name from a URL:

1 @^(?:http://)?([^/]+)@i

Also, CSS (and alt-CSS like LESS or SASS) files are also declarative:

1 body {

2 background: #f8f6f6;

3 color: #404040;

4 font-family: 'Lucida Grande', Verdana, sans-serif;

5 font-size: 13px;

6 font-weight: normal;

7 line-height: 20px;

8 }

In PHP, declarative code is achieved using higher-order functions that establish a certain vocabulary based on a few set of primitives like filter, map, reduce, zip, compose, curry, lift, etc. These are just some of the common terms used a lot with FP that you’ll learn about in this book. Once you employ this vocabulary to concoct the instructions (subroutines, functions, procedures, etc) that make up your program, the PHP runtime translates this higher level of abstraction into regular PHP code:

Shifting to a functional approach to tackle this same task, you only need to be concerned with applying the correct behavior at each element and cede control of looping to other parts of the system. I can let PHP’s array_map() do the work:

1 $square = function (int $num): int {

2 return pow($num, 2);

3 };

4 array_map($square, $array); //-> [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81]

The function array_map() also works with callables or functions just like the compose function shown earlier. Notice a trend? No? Consider this example. Suppose we also needed to add all of the values within the array. So, we need add function:

1 function add(float $a, float $b): float {

2 return $a + $b;

3 }

Now, without fiddling with the internals of the function, I use the adder to reduce the array into a single number:

1 array_reduce(array_map($square, $array), 'add'); //-> 285

Comparing this code to the imperative version, you see that you’ve freed yourself from the responsibility of properly managing a loop counter and array index access; put simply, the more code you have, the more places there are for bugs to occur. Also, standard loops are not reusable artifacts, only when they are abstracted within functions. Abstracting loops with functions will allow you to take advantage of PHP’s anonymous function syntax and closures.

Designing for immutability and statelessness

Functions like array_map() have other benefits: they are immutable, which means it doesn’t change the contents of the original array that’s passed to it.

Coding with immutable variables has many benefits such as:

- One of the main causes of bugs in software is when the state of an object inadvertently changes, or its reference becomes null. Immutable objects can be passed around to any function and their states will always remain the same. You can count on having the peace mind that state is only permitted to grow but never change. It eases the “cognitive load” (the amount of state to keep track of in your head) of any single component of your system.

- Immutable data structures are important in shared memory multithreaded applications. We won’t talk much about concurrent processing in this book because PHP processes run in isolation for the most part. Now, whether designing for parallelism or not, stateless objects is a widely used pattern seen in many common PHP deployments. For example, as a best practice, Symfony services (or service objects) should always be stateless. A service shouldn’t persist any state and provide a set of transient functions that take in the domain its working on, perform some kind of computation of business logic, and return the result.

Unfortunately, unlike Scala, F#, and others, PHP provides very poor support for immutable variables. You’re only options really are using the define function or const keyword. Here’s a quick comparison of the two:

-

constare defined at compile time, which means compilers can be clever about how to store them, but you can’t conditionally declare them (which is a good thing). The following fails in PHP 7:

1 if (<some condition>) {

2 const C1 = 'FOO';

3 }

4 else {

5 const C2 = 'BAR';

6 }

- Constants declared with ‘define’ are a bit more versatile and dynamic. Because the compiler won’t attempt to allocate space for them until it actually sees them. So you can do this:

1 if (<some condition>) {

2 define('C1', 'FOO');

3 }

4 else {

5 define('C2', 'BAR');

6 }

But you should always check if a constant has been defined with defined($name) before accessing its value using constant($name).

-

constproperly scopes constants into the namespace you’re class resides in.definewill scope constants globally by default, unless the namespace is explicitly added. -

constbehaves like any other variable declaration, which means it’s case sensitive and requires a valid variable name. Becausedefineis a function, you can use it to create constants with arbitrary expressions and also declare them to be case insensitive if you wish to do so.

All things considered, const is much better to use because it’s an actual keyword and not just a function call, which is what constants should be. Perhaps in the future, PHP moves in the direction of allowing this class-level only feature to be used anywhere to define an entity that can only be assigned once, whether it be a variable or function:

1 const $square = function (int $num): int {

2 return pow($num, 2);

3 };

Of course, as it is now, it’s unrealistic to expect that we declare all of our variables using define. But you can get close to achieving stateless programs, just like those Symfony services we spoke about earlier, using pure functions.

Pure functions fix side effects

Functional programming is based on the premise that you will build immutable programs based on pure functions as the building blocks of your business logic. A pure function has the following qualities:

- It depends only on the input provided and not on any hidden or external state that may change during its evaluation or between calls.

- It doesn’t inflict changes beyond its scope, like modifying a global object or a parameter passed by reference, after its run.

Intuitively, any function that does not meet these requirements would be qualified as “impure.” For example, while services are pure objects, repository or Data Access Objects (DAO) aren’t. This includes your Laravel Active Record objects, for example. Operations in DAOs always cause side effects because their sole purpose is to interact with an external resource, the database.

Programming with immutability can feel rather strange at first. After all, the whole point of imperative design, which is what we’re accustomed to, is to declare that variables are to mutate from one statement to the next (they are “variable” after all). PHP doesn’t make any distinctions between values (immutable variables) and standard variables–they’re all declared with the same “$” dollar sign. This is a very natural thing for us to do. Consider the following function that reads and modifies a global variable:

1 // resides somewhere in the global

2 // space (possibly in a different script)

3

4 $counter = 0;

5

6 ...

7

8 function increment(): int {

9 GLOBAL $counter;

10 return ++$counter;

11 }

You can also encounter side effects by accessing instance state through $this:

1 class Counter {

2 private $_counter;

3

4 public function __construct(int $init) {

5 $this->_counter = $init;

6 }

7

8 ...

9

10 public function increment(): int {

11 return ++$this->_counter;

12 }

13 }

Because we don’t have support for immutable variable modifiers, with a bit of discipline, we can still achieve the same goal. One thing we can do is stop using global variables and the GLOBAL mechanism in PHP. This is not only considered bad practice from a functional point of view, but also a bit frowned upon in modern PHP applications. A function like increment is impure as it reads/modifies an external variable $counter, which is not local to the function’s scope (it could actually live in a complete different file).

In addition, in the case of object methods, using $this is automatically accessing the methods’s external instance scope. While this isn’t nearly as bad as global scope, from a pure FP perspective, it’s also a side effect.

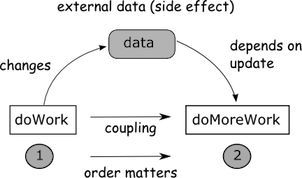

Generally speaking, functions have side effects when reading from or writing to external resources. Matters get worse, when this state is shared:

In this case, doWork and doMoreWork are very tightly coupled. This coupling means that you necessarily need to invoke doWork before calling doMoreWork, always in that order. Hence, you lose the autonomy of these functions and make them harder to unit test in isolation. Side effects create a temporal coupling or dependency, which means the execution of one can determine the outcome of the next. The result of doMoreWork is reliant on doWork. In functional programming, functions should behave like reusable artifacts that can be evaluated in any order and continue to yield correct results.

Not all side effects are this obvious. Some of them are embedded into language level functions. Frankly, you should be wary of functions that use parameter references &, such as:

1 bool sort ( array &$array [, int $sort_flags = SORT_REGULAR ] )

Instead of returning a new sorted array, it sorts the array in place and returns a (arguably useless) boolean result:

1 $original = ['z', 'a', 'g'];

2 sort($original);

3 $original; //-> ['a', 'g', 'z'];

Here are some other forms:

- Changing a variable, property or data structure globally

- Changing the original value of a function’s argument

- Processing user input

- Throwing an exception, unless it’s caught within the same function

- Printing to the screen or logging

- Querying the DOM of an HTML page and browser cookies

- Writing to/reading from files and databases

So, now you need to ask yourself: What practical value would you get from a program that couldn’t do any of these things? Indeed, pure functions can be very hard to use in a world full of dynamic behavior and mutation– the real world. But, to benefit from functional programming you don’t need to avoid all of these; FP just provides a framework to help you manage/reduce side effects by separating the pure code from the impure. Impure code produces externally visible side effects like the ones listed above, and in this book you’ll learn ways to deal with this.

For instance, I can easily refactor increment to accept the current counter:

1 function increment(int $counter): int {

2 return ++$counter;

3 }

This pure function is now not only immutable but also has a clear contract that describes clearly the information it needs to carry out its task, making it simpler to understand and use. This is a simple example, of course, but this level of reasoning can be taken to functions of any complexity. Generally, the goal is to create functions that do one thing and combine them together instead of creating large monolithic functions.

Referential Transparency

We can take the notion of purity a step further. In functional programming, we redefine what it means to create a function. In a sense we go back to basics, to the maths, and treat functions as nothing more than a mapping of types. In this case, its input types (arguments) to its output type (return value). We’ll use a pseudo Haskell notation throughout the book when document a function’s signature. For example, f :: A -> B is a function f that takes an object of A and returns an object of type B. So, increment becomes:

1 increment :: int -> int

Essentially the arrow notation is used to define any callable. A function like toFile, which returns a function from another function, is defined as:

1 toFile :: string -> string -> int

Functions in mathematics are predictable, constant, and work exactly like this. You can imagine that A and B are sets that represent the domain and the codomain of a function, respectively. For instance, the type int is analogous to the set of all integers Z. Functions that return the same values given the same input always, resembling this mathematical property, are known as referentially transparent (RT). A RT function can always be directly substituted or replaced for its computed value into any expression without altering its meaning. In other words, these are all equivalent:

1 add(square(increment(4)), increment(16)) =~ add(square(5), 17) =~ add(25, 17) =~\

2 25 + 17 = 42

This means that you can use the value 42 in place of any of these expressions. This conclusion can only be reached when there are no side effects in your code. Using RT functions we derive the following corollary. Because there are no side effects, a function’s return value is directly derived from its input. Consequently, void functions A -> () as well as zero-arg functions () -> A will typically perform side effects.

This makes your code not only easier to test, but also allows you to reason about entire programs much easier. Referential transparency (also known as equational correctness) is inherited from math, but functions in programming languages behave nothing like mathematical functions; so achieving referential transparency is strictly on us, especially in a non-pure functional language such as PHP. The benefit of doing is is that when your individual functions are predictable, the sum of the parts is predictable and, hence, much easier to reason about, maintain, and debug, and especially test.

Later on, you’ll learn that functional programs are inherently testable, because referential transparency surfaces another principle of good tests, idempotency. An idempotent unit test is a fancy term to describe a unit test that’s repeatable and consistent, so that for a given set of input you’re guaranteed to compute the same output, always. This “contract” will then be documented as part of your test code; in essence, you get self-documenting code.

By now you realize why pure functions are the pillar of FP, but we have one more concept to introduce. If pure functions are the pillars, then composition is the base or the glue that makes up the entire system.

A look into functional decomposition

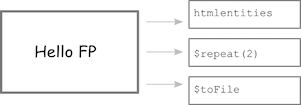

At the core, functional programming is effectively the interplay between decomposition (breaking programs into small pieces) and composition (glueing the pieces back together). It is this duality that makes functional programs modular and so effective. As I mentioned previously, the unit of modularity, or “unit of work” is the function itself. Thinking functionally typically begins with decomposition or learning to break up a particular task into logical subtasks (functions). Because the modularity boundary is the function, we can identify three components in the “Hello FP” program earlier:

Modularization in functional programming is closely related to the Singularity principle (one of the SOLID design principles), which states that functions should have a single purpose. The idea is that you learn to decompose programs into the simplest reusable units of composition. In FP, your functions should abide by this motto:

Loosely coupled + highly cohesive = No side effects + single purpose

Purity and referential transparency will encourage you to think this way because in order to glue simple functions together they must agree on their types of inputs and outputs as well as arity or number of arguments. You can see how using PHP 7’s strict typing helps in this regard, because it helps you paint the flow of your program’s execution as it hops from one function to the next. In short, they must agree on their exposed contracts, which is very similar to the Coding to Interfaces OO design principle. From referential transparency, we learn that a function’s complexity is sometimes directly related to the number of arguments it receives. A practical observation and not a formal concept indicates that the lower the number of function parameters, the simpler the function tends to be.

This process is essentially what compose does. Also called a function combinator (for obvious reasons), compose can glue together functions in a loosely decoupled way by binding one function’s output to the next one’s input. This is essentially the same coding to interfaces but at a much lower level of granularity.

To sum up, what is functional programming?

With all of this so far, we can pack the fundamental FP principles into the following statement:

“Functional programming refers to the declarative evaluation of pure functions to create immutable programs by avoiding externally observable side effects.”

Hope you’ve enjoyed this brief introduction of some of the topics covered in this book. In the next chapters we’ll learn what enables PHP to be used functionally. In particular, you’ll learn about higher-order, first-class functions, and closures, and some practical examples of using each technique. This will set the stage for developing data flows in chapter 3. So stay tuned!