Higher-order PHP

I mentioned in chapter 1 that functional programming is not a new framework, library, or design pattern. Rather, it’s a way of thinking that offers an alternative to the way in which you design your code. However, paradigms by themselves are just abstract concepts that need the right host language to become a reality. And, yes! PHP is that language. In this chapter, we’ll take a look at two important features of PHP that make functional possible: higher-order functions and closures. Both of these are instrumental in building all of the techniques you’ll learn about in this book. The goal of this chapter is to teach you how to use functions in a very different way–the functional way.

PHP’s first-class, higher-order functions

A higher-order function is defined as one that can accept other functions as arguments or return another function. This is in direct relationship with another term you might’ve heard before, that is first-class functions. Both are intimately related, as the ability of a language artifact to be passed in as an argument or returned from a functions hinges on it being considered just another object. This also means, of course, that functions can be assigned to variables. Let’s take a look at a few examples:

Functions in PHP can be manipulated just like objects. In fact, if you were to check the type of a function, you’ll find out that they are instances of the class Closure:

1 var_dump(function () { });

2

3 //-> class Closure#1 (0) {

4

5 }

If functions behave like objects, it’s logical to think we can assign them to variables.

Assigning to a variable

This means that you should be able to treat a function just like any other type of object. Which means that they can be assigned to variables. Consider a simple string concatenation function:

1 $concat2 = function (string $s1, string $s2): string {

2 return $s1. ' '. $s2;

3 };

4

5 $concat2('Hello', 'World'); //-> 'Hello World'

Behind the scenes this code takes the anonymous function (RHS) and assigns it to the variable $concat2 (LHS). Alternatively, you can check for the presence of a function variable using is_callable():

1 is_callable($concat2) // 1

Returned from a function

Functions can also be returned from other functions. This is an extremely useful technique for creating families of functions. It’s also the main part of implementing argument currying, which you’ll learn about in later chapters. Consider a simple concatWith function:

1 function concatWith(string $a): callable {

2 return function (string $b) use ($a): string {

3 return $a . $b;

4 };

5 }

6

7 $helloWith = concatWith('Hello');

8 $helloWith('World'); //-> 'Hello World'

As a parameter

Supplying functions as parameters allows you to administer specialized behavior on top of another function. Suppose I create a simple function that takes a callable and applies it over its other parameters:

1 function apply(callable $operator, $a, $b) {

2 return $operator($a, $b);

3 }

Through the callable, I can inject any behavior I want:

1 $add = function (float $a, float $b): float {

2 return $a + $b;

3 };

4

5 $divide = function (float $a, float $b): float {

6 return $a / $b;

7 };

8

9 apply($add, 5, 5); //-> 10

10

11 apply($divide, 5, 5); //-> 10

Consider a version of apply that’s a bit more useful and expressive:

1 function apply(callable $operator): callable {

2 return function($a, $b) use ($operator) {

3 return $operator($a, $b);

4 };

5 }

This function is very explicit in what it’s purpose is, and how I can use it to derive other types of functions from it. Let’s go over some simple examples:

1 apply($add)(5, 5); //-> 10

2

3 apply($divide)(5, 5); //-> 1

4

5 // New function adder

6 $adder = apply($add);

7 $divider = apply($divide);

8

9 $adder(5,5); //-> 10

10 $divider(5,5); //-> 1

I mentioned earlier that higher-order functions allow you to supply specialized behavior via function arguments. Let’s see this in action. What would happen if I call apply($divide)(5, 0)? Correct, a division by zero error:

1 Warning: Division by zero in .../code/src/ch02/ch02.php ...

To fix this, I’ll create a function called safeDivide that supplies extra null-check logic. This function is a lot more resilient, returning PHP’s NAN constant back to the caller instead of an exception.

1 function safeDivide(float $a, float $b): float {

2 return empty($b) ? NAN : $a / $b;

3 }

4

5 apply($safeDivide)(5, 0); //-> NAN

The other reason why I prefer this approach is that checking for NAN requires a lot less effort and it’s much cleaner than having to try and catch exceptions:

1 try {

2 $result = apply($safeDivide)(5, 0);

3 ...

4 return $result;

5 }

6 catch(Exception $e) {

7 Log::error($e->getMessage());

8 }

I think this is a much cleaner API design:

1 $result = apply($safeDivide)(5, 0);

2 if(!is_nan($result)) {

3 ...

4 return $result;

5 }

6 else {

7 Log::warning('Math class occurred! Division by zero!');

8 }

This approach avoids throwing an exception altogether. Recall from chapter 1 that throwing exceptions is not only a side effect, as it causes the program stack to unwind and logs written, but also doesn’t respect the Locality Principle of code. In particular, it fails to obey spatial locality, which states that related statements that should be executed sequentially shall be placed near each other. This has more application on CPU architecture, but can also be applied to code design.

Before I leave this topic of passing functions as arguments, it’s important to mention that you may pass any user-defined function variable as an argument, as well as most native to PHP, but not the ones that are part of the language such as: echo, print, unset(), isset(), empty(), include, require, require_once, and others. In these cases, your best bet is to wrap them using your own.

To recap, higher-order functions are possible in PHP because, as of PHP 5.3, they are actually Closure instances behind the scenes. Before this version, this was just considered an internal design decision, but now you can reliably take advantage of it to approach problems very differently. In this book, you’ll learn to master higher-order functions.

Furthermore, because functions are true instances, as of PHP 5.4 you can actually invoke methods on them which gives you more control of an anonymous function after it’s been created (as you might expect, Closure instances all implement the magic method __invoke(), which is important for consistency reasons with other classes).

Heck, even plain objects are invokable

Aside from having true first-class, higher-order functions, PHP takes it to the next level with invocable objects. Now, this isn’t really a functional concept whatsoever, but used correctly it could be a pretty powerful technique. In fact, PHP’s anonymous function syntax under the hood gets compiled to a class with an __invoke() method on it.

Now, the reason why this isn’t really a functional technique per se, is that functional programming tends to impose a clear separation of behavior and state. To put it another way, doing away with the use of this. One reason for doing this is that $this keyword is a gateway for side effects. Consider this simple Counter class:

1 class Counter {

2 private $_value;

3

4 public function __construct($init) {

5 $this->_value = $init;

6 }

7

8 public function increment(): int {

9 return $this->_value++;

10 }

11 }

12

13 $c = new Counter(0);

14 $c->increment(); //-> 1

15 $c->increment(); //-> 2

16 $c->increment(); //-> 3

The increment function is theoretically considered not pure (or impure) because it’s reaching for data in its outer scope (the instance scope). Fortunately, this class encapsulates this state pretty well and doesn’t expose any mutation methods as in the form of a setter. So, from a practical standpoint, this object is predictable and constant. We can go ahead and make this object invocable by adding the magic __invoke() method to it:

1 public function __invoke() {

2 return $this->increment()

3 }

4

5 $increment = new Counter(100);

6 increment(); //-> 101

7 increment(); //-> 102

8 increment(); //-> 103

In practical functional programming, there are many design patterns that revolve around wrapping values into objects and using functions to manipulate them. But for the most part, we’ll prefer to separate the behavior from the state. One way of doing this to keep things semantically meaningful is to prefer static functions that declare arguments for any data they need to carry out their job:

1 class Counter {

2 ...

3 public static function increment(int $val): int {

4 return $val + 1;

5 }

6 }

7

8 Counter::increment(100); //-> 101

Using containers improve your APIs

Earlier you learned that returning NAN in the event that divide was called with a zero denominator led to a better API design because it freed your users from having to wrap their code in try/catch blocks. This is always a good thing because exceptions should be thrown only when there’s no recovery path. However, we can do better. Working with numbers and NAN doesn’t really get you anywhere; for example, adding anything to NAN (ex. 1 + NAN) returns NAN, and rightfully so. So, instead of burdening your users to place is_nan checks after each function call, why not consolidate this logic in one place? We can use containers to do this.

We cans use wrappers to control access to certain variables and provide additional behavior. Looking at it from an OOP design patterns point of view, you can compare this to a Fluent Object pattern. To start with, consider this simple Container class:

1 class Container {

2 private $_value;

3

4 private function __construct($value) {

5 $this->_value = $value;

6 }

7

8 // Unit function

9 public static function of($val) {

10 return new static($val);

11 }

12

13 // Map function

14 public function map(callable $f) {

15 return static::of(call_user_func($f, $this->_value));

16 }

17

18 // Print out the container

19 public function __toString(): string {

20 return "Container[ {$this->_value} ]";

21 }

22

23 // Deference container

24 public function __invoke() {

25 return $this->_value;

26 }

27 }

Containers wrap data and provide a mechanism to transform it in a controlled manner via a mapping function. This is in many ways analogous to the way you can map functions over an array using array_map():

1 array_map('htmlspecialchars', ['</ HELLO >']); //-> [</ HELLO >]

This container behaves exactly the same:

1 function container_map(callable $f, Container $c): Container {

2 return $c->map($f);

3 }

I can call it with container_map, or I can use it directly. For instance, I can apply a series of transformations on a string fluently like this:

1 $c = Container::of('</ Hello FP >')->map('htmlspecialchars')->map('strtolower');

2

3 $c; //-> Container[ </ hello fp > ]

Notice how this looks much cleaner and easier to parse against nesting these function calls one inside the other. Personally, I rather see code in a flattened out and linear model than something like:

1 strtolower(htmlspecialchars('</ Hello FP >')); //-> </ hello fp >

I also added some PHP magic with __invoke() that can be used to dereference the container upon invocation as such:

1 $c = Container::of('Hello FP')->map($repeat(2))->map(strlen);

2 $c(); //-> 16

So, what’s the use for this pattern? Earlier I mentioned that throwing exceptions, or for that matter, the imperative try/catch mechanism has side effects. Let’s circle back to that for a moment. Arguably, try/catch is also not very declarative and belongs in the same category as for loops and conditional statements. Containerizing values is an important design pattern in FP because it allows you to consolidate the logic of applying a function chain (sequence) of transformations to some value immutably and side effect free; it’s immutable because it’s always returning new instances of the container.

This can be used to implement error handling. Consider this scenario:

1 $c = Container::of([1,2,3])->map(array_reverse);

2 print_r($c()) //-> [3, 2, 1]

But if instead of a valid array, a null value was passed in, you will see:

1 Warning: array_reverse() expects parameter 1 to be array, null given

One way to get around this is to make sure all functions you use (PHP or your own) are “safe,” or do some level of null-checking. Consider the implementation for a SafeContainer:

1 class SafeContainer extends Container {

2 // Performs null checks

3 public function map(callable $f): SafeContainer {

4 if(!empty($this->_value)) {

5 return static::of(call_user_func($f, $this->_value));

6 }

7 return static::of();

8 }

9 }

With this I don’t have to worry about the error checking to clutter all of my business logic; it’s all consolidated in one place. Let’s see it in action:

1 $c = SafeContainer::of(null)->map(array_reverse);

2 print_r($c()); //-> Container[null]

The best part about this is that your function chains look exactly the same, there’s nothing extra on your part, so you can continue to map as many functions as you need and any errors will be propagated through the entire chain behind the scenes.

Now let’s mix it up and use containers with higher-order functions. Here’s an example:

1 $c = Container::of('</ Hello FP >')->map(htmlspecialchars)->map(strtolower);

2

3 //-> Container[ </ hello fp > ]

Just for completeness sake, here’s a container called SafeNumber to tackle our division-by-zero problem earlier:

1 class SafeNumber extends Container {

2 public function map(callable $f): SafeNumber {

3 if(!isset($this->_value) || is_nan($this->_value)) {

4 return static::of(); // empty container }

5 else {

6 return static::of(call_user_func($f, $this->_value));

7 }

8 }

9 }

It looks very simple, but the effect of this wrapper type is incredible; most things in functional programming are very basic but with tremendous impact and reach. I’ll refactor safeDivide earlier to return a SafeNumber:

1 function safeDivide($a, $b): SafeNumber {

2 return SafeNumber::of(empty($b) ? NAN : $a / $b);

3 }

One thing I like about this function is how honest it is about its return type. It’s essentially notifying the caller that something might go wrong, and that it’s safe to protect the result. Also, it removes the burden of having to NAN-check any functions that are invoked with this value. I’ll show the cases of calling safeDivide with a valid as well as an invalid denominator:

1 function square(int $a): int {

2 return $a * $a;

3 }

4

5 function increment(int $a): int {

6 return $a + 1;

7 }

8

9 // valid case

10 apply(safeDivide2)(5, 1)->map(square)->map(increment); //-> Container [26]

11

12 // error case

13 apply(safeDivide2)(5, 0)->map(square)->map(increment)); //-> Container[ null ]

SafeNumber abstracts out the details of dealing with an invalid number, so that we’re left alone to worry about bigger, more important problems.

In chapter 1, I briefly mentioned that behind the scenes, all functions are instances of the Closure class. This is what enables me to map them to containers. This is important to understand, so let’s take another look at this class.

Closures

After PHP 5.4+, all functions in PHP are objects created from the Closure class. But why do we call it this way and not the more intuitive Function type (like JavaScript)? The goal behind this class is to represent anonymous functions where a closure is formed around the function as it’s being inlined into, say, a callable argument. For instance, I could use an anonymous function to perform the safe divide (I would recommend you do this only when the function is unique to the problem you’re solving and you don’t anticipate reusing it somewhere else):

1 apply2(

2 function (float $a, float $b): SafeNumber {

3 return SafeNumber::of(empty($b) ? NAN : $a / $b);

4 })

5 (7, 2); //-> Container [3.5]

They are also used extensively in modern MVC frameworks, like Laravel:

1 Route::get('/item/{id}', function ($id) {

2 return Item::findById($id);

3 });

But this doesn’t apply exclusively to the anonymous case, all functions create a closure. Unfortunately, at this point PHP doesn’t have support for “lambda expressions,” syntactically simpler anonymous functions, but there’s currently an open proposal that I hope will be included soon. Check out this RFC here for more information.

With lambda expressions and omitting type declarations, the code above would look pretty slick:

1 apply2(function ($a, $b) => SafeNumber::of(empty($b) ? NAN : $a / $b))(7, 2);

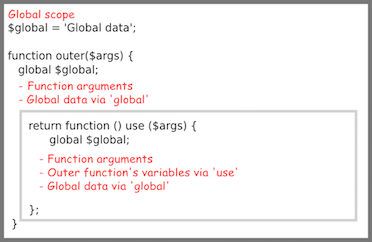

Similarly, lambda functions would also be implemented to form a closure around it. Let’s understand what this means. A closure is defined as the lexical scope created around a function declaration, anonymous or otherwise. This gives function knowledge of the state of the variables lexically declared around it. The term lexical refers to the actual placement of the variable in the code. Here’s a diagram that explains what a function inherits:

The data structure used to encapsulate the state that makes up a function’s closure is the [Closure class](http://php.net/manual/en/class.closure.php) class, hence the name. Here’s the definition for it:

1 class Closure {

2 private __construct ( void )

3 public static Closure bind ( Closure $closure , object $newthis [, mixed $new\

4 scope = "static" ] )

5 public Closure bindTo ( object $newthis [, mixed $newscope = "static" ] )

6 public mixed call ( object $newthis [, mixed $... ] )

7 }

Recall the function concatWith used earlier, and look closely at the inner function:

1 function concatWith(string $a): callable {

2 return function (string $b) use ($a): string {

3 return $a . $b;

4 };

5 }

PHP’s closure mechanism has an advantage over that of JavaScript’s in that, instead of simply capturing all of the state around an anonymous function declaration, you can explicitly declare which variables the it’s permitted to access via the use keyword.

This is incredibly powerful and allows you to have more control over side effects. Under the hood, the variables passed into use are used to instantiate its closure.

Here are some examples that reveal PHP’s internal closure object. The add function can be invoked as globally using Closure::call:

1 $add->call(new class {}, 2, 3); //-> 5

The use of PHP 7’s anonymous class here is to set the owning class of this function (in case $this is used) to something concrete. Since I don’t use $this, I can provide a meaningless object to receive $this.

You can also dynamically bind functions to object scopes using Closure::bindTo. This allows you to easily mixin additional behavior of an existing object. As example, let’s create a function that allows us to validate the contents inside a container before mapping an operation to it. In functional programming, conditional validation is applied using an operator called filter, just like array_filter is used to remove unnecessary elements. But instead of adding filter to all containers, I can mixin a properly scoped closure (in some ways this is similar to using Traits):

1 function addTo($a) {

2 return function ($b) use ($a) {

3 return $a + $b;

4 };

5 }

6

7 $filter = function (callable $f): Container {

8 return Container::of(call_user_func($f, $this->_value) ? $this->_value : 0);

9 };

10

11 $wrappedInput = Container::of(2);

12

13 $validatableContainer = $filter->bindTo($wrappedInput, Container);

14

15 $validatableContainer('is_numeric')->map(addTo(40)); //-> 42

Now consider what happens when the input is invalid according to our filter predicate:

1 $wrappedInput = Container::of('abc);

2 $validatableContainer('is_numeric')->map(addTo(40)); //-> 40

Now that you’ve learned about higher-order functions (and then some more), we’re ready to begin creating functional programs. In chapter 3 we’ll learn about function composition and point-free programs, as well as how to break problems apart into manageable, testable units.

Lastly, if you have an OOP background, here’s a nice table to keep handy that compares both paradigms which will make the rest of the material easier to digest.

Functional vs Object-Oriented Summary Table

| Traits | Functional | Object-oriented |

|---|---|---|

| Unit of composition | Functions | Objects (classes) |

| Programming style | Declarative | Mostly imperative |

| Data and Behavior | Loosely coupled into pure, standalone functions | Tightly coupled in classes with methods |

| State Management | Treats objects as immutable values (minimize state changes) | Favors mutation of objects (state) via methods |

| Control flow | Higher-order functions and recursion | Loops and conditionals |

| Tread-safety | Enables concurrent programming | Difficult to achieve |