Versioning Process Managers

Process Managers are a highly useful pattern in Event Sourced systems. There is however almost no information available via books, blogs, videos, etc on how to handle the versioning of Process Managers in a production system. This chapter will be focused on exploring Process Managers and in particular looking at how to handle multiple versions of processes in a production system.

Procees Managers

Process Managers though known by other names including Orchestrations represent a business process that spans more than a single transaction. They have a responsibility to either get the overall business process completed or to leave the system in a known termination state. If an error happens the Process Manager may or may not handle a rollback procedure.

Process Managers represent the handling of the overall business process. As example when an OrderPlaced event is received the system could start an OrderFulfillment Process Manager that will handle the overall process of fulfilling the order. If along the way there are issues that occur within the the system the Process Manager will either handle those errors automatically or detect that they have occurred and notify a customer service representative or system administrator who will manually deal with the errors.

These business processes are often quite valuable to the business overall. Oddly in many systems they are not actually modelled in any way but are instead in the minds of the users. While modelling explicit Process Managers is often a good idea, the versioning of a processes in an organization can at times be tricky.

Basic Versioning

The most simple and generally preferred method of handling versioning of business processes is to handle it in the same way that the organization itself tends to handle it.

When introducing a change to a business process in an organization it is rare to introduce it as a change. Instead organizations will tend to introduce a new business process. This new business process will affect all instances of the business process that occur after a given point in time which is used as a cut off date.

If for example a bank were to introduce a new process for the approving of mortgages they would introduce it as a new business process. An email would come from the group managing the process that as of March 13th all new mortgage applications would go through the new process. There will be mortgage applications that were received on March 12th that will continue to go through the old application process.

There is a reason that organizations tend to introduce changes to a process as a new process. In particular it can be difficult to change mortgage applications that were running on the old process to instead run on the new process. The old process and the new process may or may not be compatible and changing a mortgage running through the old application process may not be possible.

Once a Process Manager is running in production there will no longer be changes to that business process. The code of the Process Manager should be read-only. Any changes to the business process will result in a new Process Manager being shipped to production. This new Process Manager will also usually have a start time associated with it. All processes that start before noon on Tuesday will use the old Process Manager any that come after this point in time will use the new Process Manager.

There are many advantages to using this style of release. One of the largest gains is in terms of predictability. Changing processes as they are running is a dangerous operation. It is quite likely that the change will leave some instances of the Process Manager waiting on things that will never occur. Processes that end up waiting indefinitely on something that will never occur are also fondly called “zombies”.

Though not about versioning it is important when writing Process Managers to never wait infinitely on something. You can wait for Int64.MaxValue 3,372,036,854,775,807 seconds which is roughly 292,471,208,678 years but it is still not infinite. Ideally your timeouts should be much lower (days at most). This will allow an instance of a Process Manager that has gotten into an odd state to timeout and hopefully recover or notify somebody about the failure that has occurred.

If you can get to the point of having all changes to processes being released as new processes, versioning will not be a major issue. There is always a cutoff point and things before that will run on the old process, things after on the new process. There is no versioning needed in this case. Process Managers enable the ability to have multiple concurrent business processes as there is an instance of the Process Manager per thing that is being managed. It is a common pattern as well to have multiple business processes based on some attribute of the initial event (is this an order less than $5 or an order > $1m, each could have its own process).

While bringing in new Process Managers at a point in time and leaving the old processes running to conclusion is the ideal, it is not always possible. Most Process Managers run over a time span of seconds to days. For these types of processes you can usually use the cutoff strategy described. Organizations tend to use the same versioning structure discussed at an organizational level anyways so it is a good fit. What if the process was a multiple year process?

Upcasting State

When dealing with say a multiple year long process there are times where it is necessary to change not just what the future instances of the process will do but also the ones that are currently running. As the process duration becomes longer versioning becomes more important. This is a niche use case but one that it worth covering.

An example of this can be seen in a Process Manager that manages the balancing of funds in a trading plan. It could run for years, and there will be times when changes need to be made to existing instances of the process while they are running.

This changing of the process while it is running is a dangerous operation. As mentioned previously, a change can leave a running process in a state where it will never receive what it is waiting for. Another possibility is that due to the change the process may end up duplicating operations.

The duplication of operations and possible complications that can arise from it is easy to see with a simple example process. In a restaurant the business process could be either to have the customers pay before receiving their food or they could pay after receiving their food. If there was an order that was set to pay before it had its food, and the business process was changed to make the customer pay after they received their food it is quite possible that the process would attempt to have the customer pay twice.

While it is a niche situation that a Process Manager would be upgraded in place it is important to cover how to handle this case.

Direct to Storage

Many frameworks offer no explicit concept of changing the version of a running Process Manager. Instead the recommendation is to go to the database that is backing the Process Managers and update the state in the data store. This is a highly dangerous operation and should be avoided if at all possible.

At first it can seem to be a relatively simple thing to do. Issue an update statement against the backing storage and then all of the states are upgraded. How will this work when the system is running at the same time that the upgrade is taking place? What if a mistake is made? Ideally this backing storage should be a private detail of the framework not something you directly interact with.

New Version Migrates

In order to avoid the direct updating of underlying storage some frameworks offer an explicit method of handling an upgrade. The framework itself understands the concept of multiple versions of a Process Manager and can also understand when what was a v1 is now being upgrade to a v2. The frameworks generally offer a hook to the Process Manager at this point where the new version of the Process Manager can decide how to upgrade the old version of the state.

1 public class MyProcessManager_v1 : WithState<State_v1> {

2 private State_v1 state;

3 }

1 public class MyProcessManager_v2 : WithState<State_v2>, Upgrades<State_v1> {

2 private State_v2 state;

3

4 public State_v2 MigrateState(State_v1 state) {

5 return new State_v2();

6 }

7 }

The code example above is a common implementation of a state migration as supported by the underlying framework. When the new version is used for the first time, the framework will see that the old version (v1) used a State_v1 state. The framework will then call into the MigrateState method passing the old state to the new version to allow for a migration before it passes the message into the new version of the Process Manager.

It is important to note that since MigrateState is just a method the new version of the Process Manager may even decide to interact with other systems in order to migrate the state. A common example of this would be the old version only kept accountId but the new version requires accountNumber as well that it under normal running saves off of messages.

Another benefit is that since the migration is happening as part of the delivery of the message this mechanism can also be run while continuing to process messages. The system does not need to be shutdown during the migration process though it may operate in a degraded way depending upon the complexity and interactions of the migration method.

The migration method at least removes the problem of directly interacting with the private Process Manager state storage. Not all frameworks support this type of migration. In general even if your framework supports this type of migration you should probably avoid it as there is another more idiomatic way of handling the migration.

Take Over

As stated at the beginning of the chapter, it is best to let a Process Manager run to its end under the same version that it was started on. Changing a Process Manager while it is running is a tricky and dangerous operation. Explicit migration support from whatever framework you are using can help to mitigate some of the issues associated with the switching of versions but not all.

Of particular concern with the in place migration is that it can become very difficult to debug. When exactly did the migration occur, on which message? Some frameworks offer logging capabilities to show when it occured but not all. It is common to run into situations looking back where it is unclear which version of the Process Manager was running at which times. This is especially if you have messages that arrive close temporally to the release of the new version or if you have multiple servers and roll out the new version incrementally.

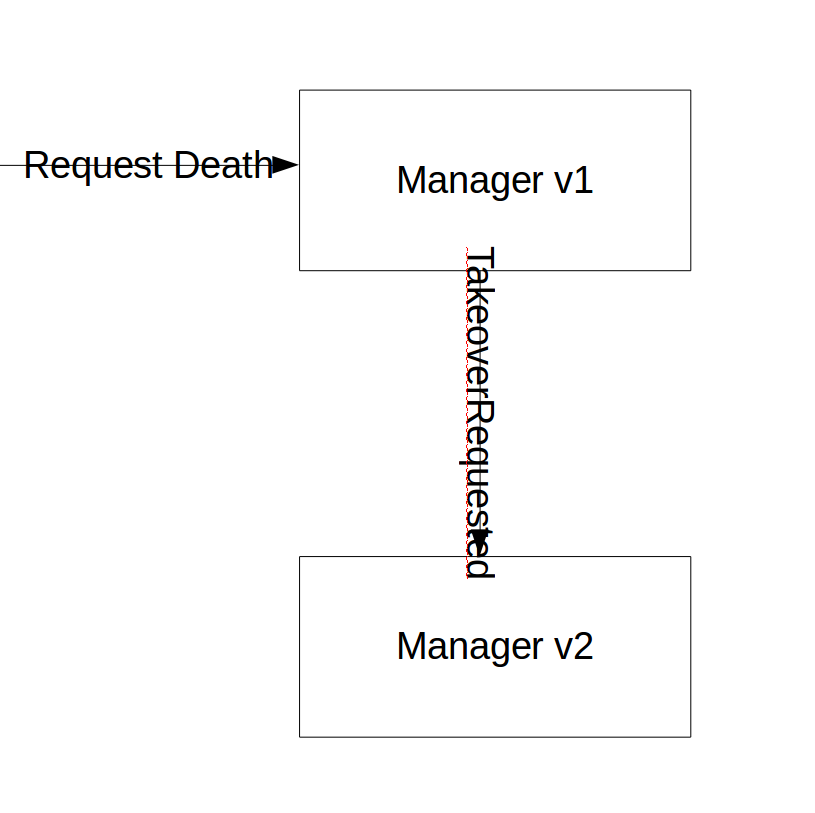

There is another option that can be used known as a Takeover or a Handoff that can help with both of these issues. Instead of upgrading in place the previous version of the Process Manager is told to end itself, it will then with its last dying breath raise a message “TakeoverRequested” that will start off the new version of the Process Manager.

Upon handling the “EndYourselfDueToTakeover” message the previous version of the Process Manager can do any clean up work that it wants based on its state. As example if it had previously taken a hold on a credit card as part of a sales process, it can release the hold. It leaves the process in a known end status. Once it is in a known end status it will then raise the “TakeoverRequested” message on the same Correlation Id. In raising this message it can put any relevant state that it has into this message. Once this message is raised, it is considered terminated.

The new version of the Process Manager will be associated to run on the “TakeoverRequested” message. It will then start up and enter into its workflow based upon the state in the take over message as opposed to its normal entry point.

This strategy keeps with the original goal of letting the original Process Manager run to the end of its life cycle. It will simply pass control to the new version. Another large benefit is that since the handover is done via a message on the same Correlation Id there is a record of exactly when the take over occured contained in the actual message stream and indexed by Correlation Id for debugging purposes.

Of all the choices looked at thus far the Takeover is the cleanest strategy. What is also nice about the Takeover strategy is that it does not require any explicit framework support to work. As such it is a framework agnostic strategy which can also help with removing coupling surface area from a framework.

Another point to consider especially for longer running processes is to break them apart into multiple Process Managers. If as example you have a single Process Manager that is responsible for everything from the time a mortgage application comes into the bank until it has been securitized and sold, versioning will be extremely difficult. Breaking this large process up into multiple related sub-processes will make versioning the sub-processes more simple as each is a smaller set of operations resulting in a smaller number of possible takeover scenarios ybiund that would be involved.

There are however another strategy that in some scenarios can make state management easier.

Event Sourced Process Managers

It being the book is about Versioning of Event Sourced systems, it is only natural to bring in the concept of Event Sourced Process Managers. Many frameworks such as Akka.Persistence use this mechanism by default. Many other systems are unable to support it as it requires the ability to replay previous messages.

As discussed previously when discussing models and state in general, one advantage of storing events as opposed to storing state is that state is transient

One major problem with any form of state migration shown is that the previous version of the Process Manager may have not saved enough information for the new version to be able to build up the state that it needs. An example of this could be that the previous version of the Process Manager never saved what the customer this order was for as it did not need it. The new version requires a credit/terrorism check on the customer before the order can be completed. When attempting to migrate the state this information does not exist.

There could be some process where the new Process Manager might go and talk to other services to try to determine this information but this can quickly become complex, and there may not be a service that has the information that is required. The information may only exist on the previous messages. A good example of this is an indentifier returned earlier from a third party that now needs to be sent back on a message in the future.

Event Sourced Process Managers can help in this situation. Instead of keeping state off in a state storage the Process Manager is rebuilt by replaying the messages it has previously seen. This gives all of the versioning benefits of working with transient state seen earlier in the book.

Interesting how the framework maintains Event Sourced Process Managers and how they are tested is very closely related. Tests for Event Sourced Process Managers are generally all structured in the same format.

1 public void TestSomethingOnMyProcessManager() {

2 //arrange

3 var fakePublisher = new FakePublisher();

4 var process = new MyProcessManager(fakePublisher);

5 process.Handle(new MyMessage1(...));

6 process.Handle(new MyMessage2(...));

7 process.Handle(new MyMessage2(...));

8 fakePublisher.Clear();

9 //act

10 process.Handle(new MyMessage4(...));

11 //assert

12 Assert.That(fakePublisher.OnlyContains<MyMessage>(x => x.Id == 17));

13 }

14

15 A> Note that Event Sourced Process Managers tend to only receive and raise even\

16 ts, they will not as example open up a HTTP connection and directly interact wi\

17 th something directly.

This test written in AAA style shows the pattern that is typically used to test an Event Sourced Process Manager. A Fake Publisher is used for the test. The Fake Publisher will basically take any messages that are published to it and put them into a list in memory that can later be asserted off of.

During the Arrange phase the Process Manager is built and messages are passed into it. It will publish any messages it wishes to the Fake Publisher. At the end of the Arrange phase the last line of code is always fakePublisher.Clear which will clear the Publisher of any messages generated during the Arrange phase. It is only wanted to Assert off the messages that occur during the Act phase not during the Arrange, these would have other tests associated with them.

The Act phase pushes in a single message and only ever a single message. There should only ever be a single line of code in the Act phase and it should be pushing a message into the Process Manager.

The Assert phase will then assert off of the messages that are in the Publisher. As the Publisher was cleared before the Act phase there will only be messages associated with the operation done in the Act phase. All assertions will be done on messages, there should not be an assert off the state of the Process Manager etc.

This same process can be applied to a Process Manager framework. Instead of loading up state then pushing a message into the Process Manager the framework builds the Process Manager and pipes its output to /dev/null replays all of the messages the Process Manager has seen previously into the Process Manager. Once the replay has occured the framework then connects the Process Manager to a real publisher (normally this is just handled by an if statement on the publisher). When the actual message is then pushed into the Process Manager any publishes that it does will be considered real publishes.

In other words the Process Manager is rebuilding its state on every message that it receives, much the same as an aggregate would rebuild its state off of an event stream in the domain model. For performance reasons it is not common to actually rebuild the full state on every message it receives. Instead the current state is cached (memoized) either in memory or in a persistent manner. The main difference is that the cached version is transient and only a performance optimization.

The state of the Process Manager can at any point be deleted and recreated. This is an especially useful attribute when discussing a new version of a Process Manager that needs to replace a currently running Process Manager. All that is required is to delete the currently cached version of state and let the new version of the Process Manager replay through the history to come to its concept of what the current state is.

This also handles the case of the previous version not having in its state things that will be needed by the new version of the process. In the previous case there was an identifier on a message that the old version did not care about but the new one does. When the new version gets replayed, it will see that message and be able to take whatever it wants out of it to apply to its own state.

Unfortunately everything is not puppies and rainbows. There is inherent complexity in bringing a new version of a Process Manager to continue from an old version of the Process Manager. The new version must be able to understand all the possible event streams that result from the previous version, or at least what it cares about. Often times this is not a huge problem but it depends how different the processes are between the two versions. This can result in a large amount of conditional logic for how to handle continuing on the new process where the old process had left off.

This versioning of Event Sourced Process Managers is often used in conjunction with the Takeover pattern. The old version is signaled that it is to terminate. It can still do anything that it wants as part of its termination and it then raises the “TakeoverRequested” message that will start the new version. The main difference with Event Sourced Process Managers and the pattern is that they do not send state when they ask the new version to Takeover.

Warning

When versioning Process Managers there are many options. The majority of this chapter however is focused on difficult edge conditions. Situations where a running process is changed while it is running should be avoided. All of the cases where a running process is changed while running are niche scenarios, they are included as the topic of the book is versioning. In most circumstances if you are trying to version running Process Managers, you are doing it wrong. Stop and think why it is needed, likely you have a modelling issue. Why does the business want to upgrade the processes in place? There are valid reasons but it is worth looking deeper.

Instead focus on releasing new processes in the same way the business does. When releasing a new version the new version takes future versions of the process. The currenty running versions stay on the old version. It is not a “new version” of the Process Manager but a new Process Manager. This method of versioning is far simpler, your hair and your sanity will thank you.