Copy and Replace

Copy and replace (or Copy-Replace) is a pattern that can solve many types of versioning problems in an Event Sourced system. Have two events that need to be merged into one, or one event that needs to be split into two? This will do. You can even use it to update an event.

Travelling around talking with varying teams, I have found a huge number of them have given up on most of the other versioning strategies and just use Copy-Replace. If nothing else, it is clear the pattern has become quite popular over the last few years.

Simple Copy-Replace

Copy and replace is a relatively easy pattern to get started with. It can technically fix any issue you could ever encounter in a stream. Have 27 events and want 3? No problem. If using the versioned typed strategies, you can even use a Copy-Replace to upgrade all of those events to the latest version while avoiding the need to upcast events to the latest version.

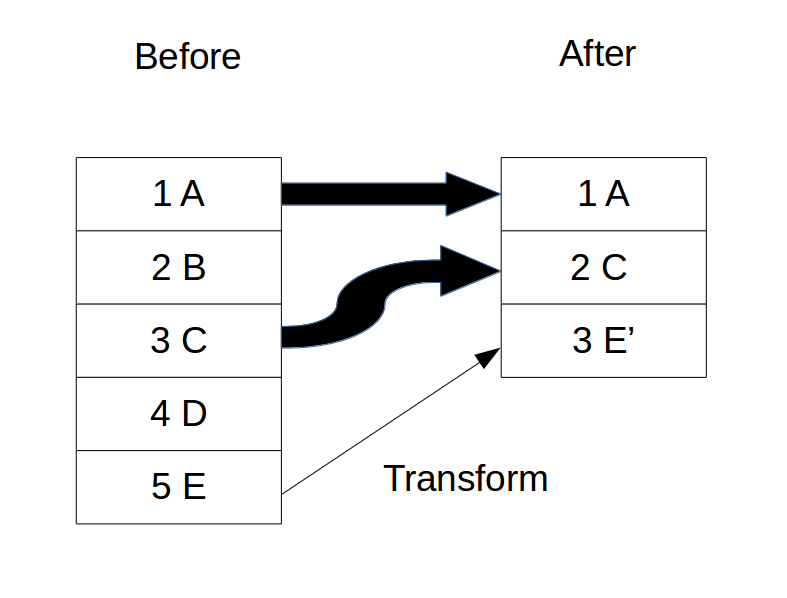

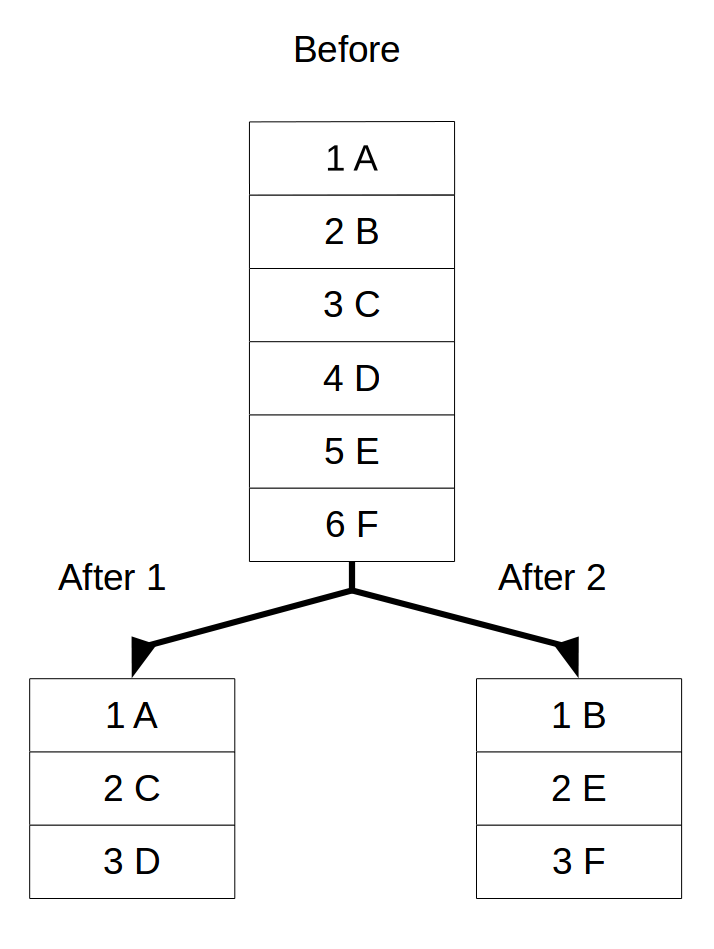

The general idea is to read the events out of the old stream and write them to a new one. You can forgo reading them all at once into memory (though for some types of transformations you may want to) and, instead, go one or a few at a time with a buffer. This can be seen in Figure 1.

Once you have this operation in place, it is possible to add a transformation step in the middle. For example, to get rid of events, they would just not be copied. To transform events from one version to another, they could be upcast. Any merging and splitting of events can be done easily. Any transformation can sit in the middle.

In Figure 1, the Before stream contains 5 events, A,B,C,D,E, which are read up and written back into the After stream as need be. When the transformation is complete, the After stream contains events A,C, and E’, which is a transformation of the E event. The B and D events were not important, so they were not copied.

After the entire stream has been read through and the new stream created, the original stream is then deleted.

In Place Copy-Replace

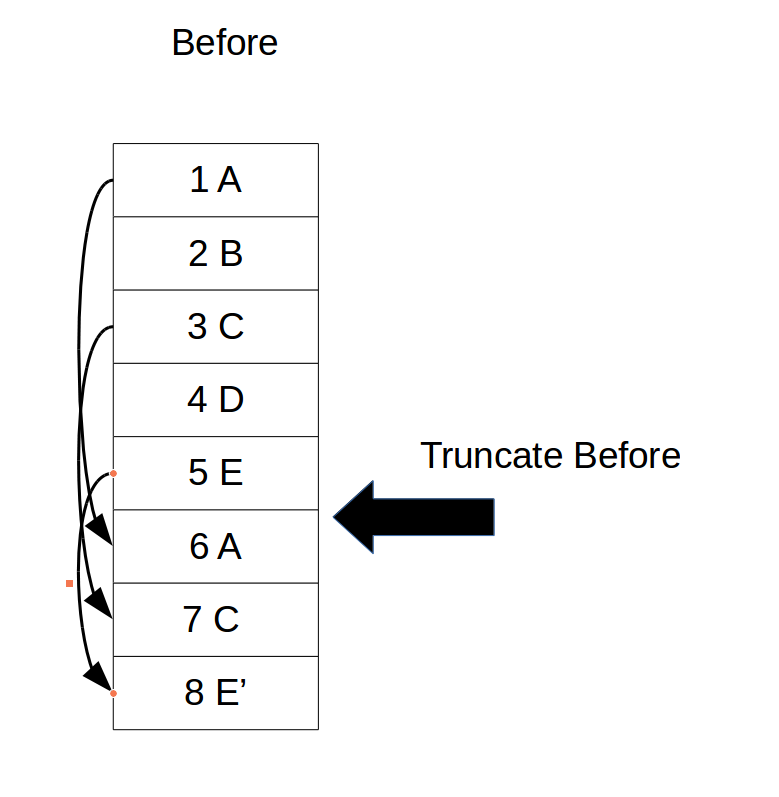

Some Event Stores also support a “truncate before” operation, which deletes all events prior to event X. If this operation is supported, there is a slight variation of this pattern shown in Figure 2.

The only difference between this pattern and the original copy and replace one is that it is being done on the same stream. Instead of writing to a new stream, the events are appended back to the end of the same stream. All that’s necessary to make this work is to remember the first event that was written as part of the “new” stream and to ensure reading stops at that point. In Figure 2, for instance, the first event written is event 6, so you would stop reading at event 5. The delete operation is then either to use a “truncate before” or to update a pointer telling you where the beginning of the stream is.

Simple>

Both of these patterns are quite easy to implement — dangerously so. It is also quite easy to become dependent on them. As these operations can handle any possible case, it may start to seem best to just use them all the time and forget about all the other versioning approaches discussed. Why fuss over compensating actions when you can just remove the original offending event from existence?

It is not so simple.

While it may seem very simple, there are many ramifications to such types of operations.

Copy-Replace is the nuclear-option of versioning.

Consumers

What happens to consumers when When this operation is performed? Whether projections or other consumers, these may, for example, charge a credit card. Imagine that event A in Figure 2 is OrderPlaced, which should trigger an email to be sent.

Admiteddly, I am likely to blame for the current popularity of Copy-Replace. In my blog post, Why can’t I update an event, I wrote:

Occasionally there might be a valid reason why an event actually needs to be updated, I am not sure what they are but I imagine there must be some that exist. There are a few ways this can actually be done.

The generally accepted way of handling the scenario while staying within the no-update constraints to create an entire new stream, copy all the events from the old stream (manipulating as they are copied). Then delete the old stream. This may seem like a PITA but remember all of the discussion above (especially about updating subscribers!).

In retrospect, I did not speak enough to the practical downsides of the approach.

One option is to make sure you include the same identifier on the new event as the one you are copying. This works well for some cases, but what happens if there is an event split? Certainly you can’t assign the same identifier to both of the split events. Falling back on idempotency is good in most cases, but not all.

Consider, for one, the transformation that occurred in Figure 1. The Before stream contained 5 events, A,B,C,D,E, and the After stream contained 3 events, A,C,E’. If a consumer is idempotent, it will receive E’, but what if the data in E’ is materially different to the data in E? Can it really be considered idempotency when two completely different events have the same identifier but potentially drastically different information in them? Perhaps the team handling the matter is disciplined enough to decide whether or not to use the same identifier in varying cases. But quite possibly they are not.

The worst issues around Copy-Replace are still being avoided by assuming the Copy-Replace is executed in an offline manner. An administrator stops incoming transactions, runs the Copy-Replace, re-runs all projections for read models, and finally brings the system back up. As discussed in the introduction, however, this is unacceptable for most modern systems. It might be fine for a five-minute migration, but what happens when dealing with a three-hour one?

With a System Live

Once you decide to perform any form of Copy-Replace on a running system, things really start to get fun. When a Copy-Replace is run under such circumstances, the old events are transformed and appended to the log as new events. This implies that things such as projections will see them as new events.

How will projections to varying read models be notified that events B and D no longer exist? If they are idempotent and realize that event E’ is the same as E, what will they do about the different data in E’? How will they update their models to match the changes that occurred within the event store?

Next month, a decision is made to replay a read model. As a test, we capture the current read model, R1, at position P in the log. We then replay the projection for the same read model, R2, to position P. Does R1 = R2? R1 and R2 have seen different versions of history and are quite likely to be different, seeing as, after the Copy-Replace is applied, R1 no longer represents the events that are in the Event Store. Can we allow anyone to query R1 to make decisions after a Copy-Replace has been done? Provided the system is down, you could replay all projections then bring the system back up, which would remove this issue.

What happens if, in the old version of the software, a command is being processed, reads from the stream, attempts to write to the stream and is notified it is deleted? In other words, in the time it took to process the command, the Copy-Replace occurred, and now the stream is gone.

Suddenly, Copy-Replace doesn’t seem so simple.

There are some strategies that can be employed here. But not all work in all scenarios. And not all scenarios are solvable. Again, Copy-Replace is the nuclear option of versioning.

The first requirement is that both the old and new versions of the software be able to understand both the new and old versions of the stream. This sometimes happens automatically, depending on the type of transformation being applied via the Copy-Replace. If it does not, then an intermediate version must be released so the old version will understand the replacement stream. If not, when switched to the replacement stream, the old version of software will no longer work.

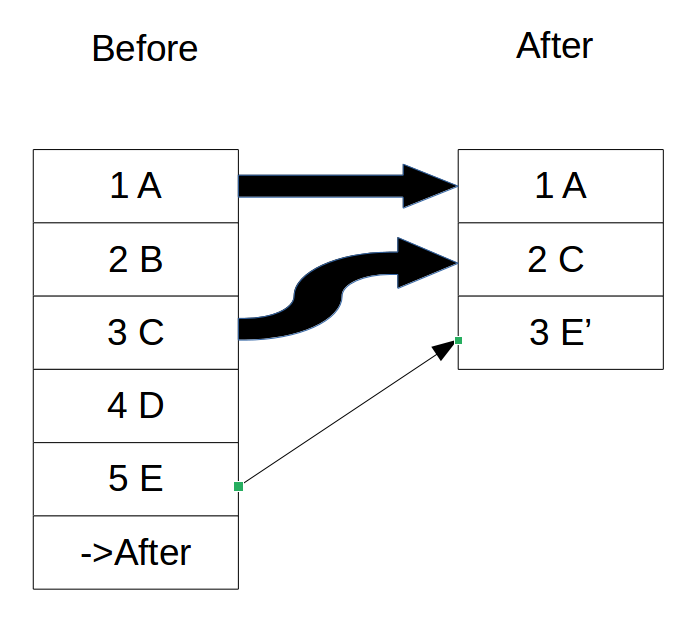

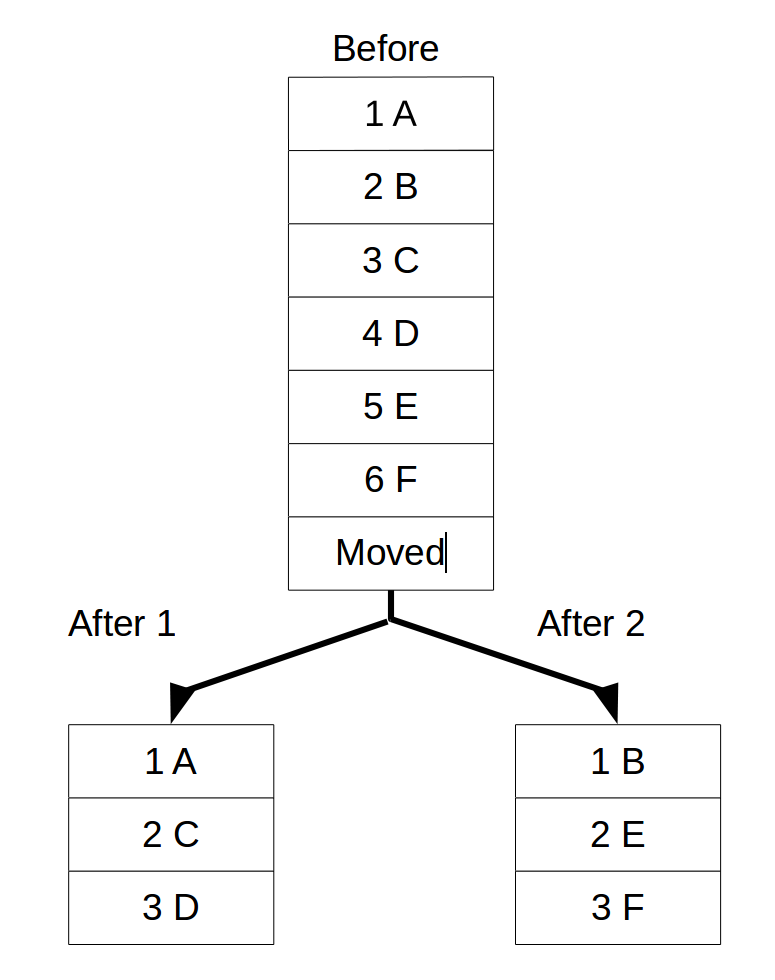

A small change will then be made to the original Copy-Replace instead of deleting the stream after. Write an event at the end of the stream saying this stream has been migrated. While seemingly a small detail, this event removes the need for the old version of the software to understand the new naming scheme that the streams will be migrated to (or perhaps they are just GUID’s). Essentially, this event will act as a pointer. A single generic event can be used for this StreamMovedTo { where : ‘…’}.

Figure 3 shows the general process discussed. The Copy-Replace will run asynchronously while the system is running. During the migration process, the producer will, when loading/writing to the stream, first check the last event in it. If it is a StreamMovedTo event, it will follow that link and use the new stream. If it is not, it will remember the version number of the event it read and use it as ExpectedVersion (even if you are using ExpectedVersion.Any normally on this write!). Using the ExpectedVersion here prevents the race condition of the stream from being migrated during the processing time.

This process will handle problems arising on the producer/write side, but, as discussed, the producer problems are not the big problems during this process. Since the events are being re-appended to the log, projections / read models are receiving these events as if they are new events.

Meanwhile, varying types of transformations may be occuring. Some transformations are reasonably safe (Upgrade Version of Event, Add New Event), some are slightly dangerous (Split Event, Merge Events) but can be worked around, and some are very dangerous (Delete Event, Update event).

To be fair, what many companies do here is just let the read models go out of sync briefly and then rebuild/replace asynchronously. If this is done a short period of time after the problem arises, the damage can often be limited and/or turned into a customer service issue. This is easier than trying to deal with the technical problem.

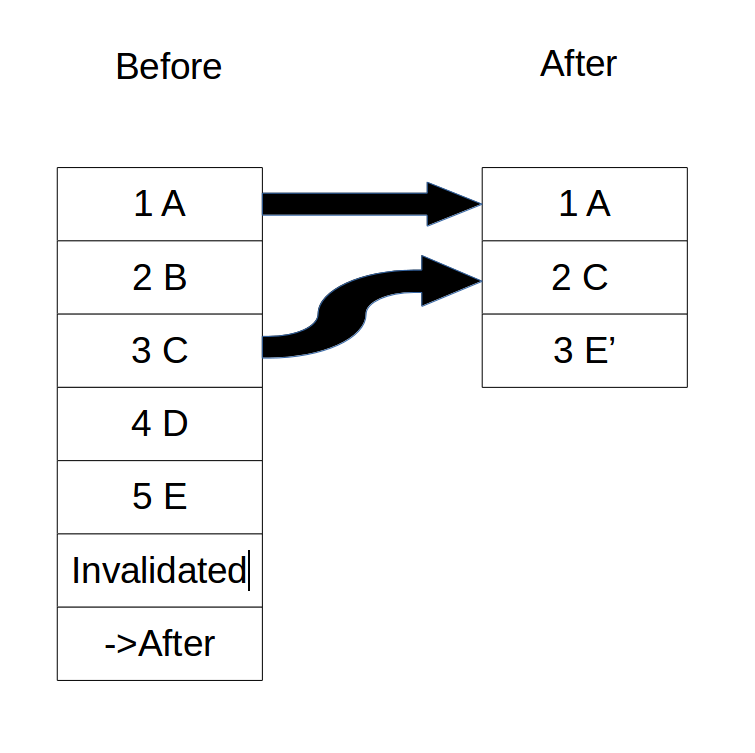

If you must deal with this, however, you need a way to signal all projections that the old stream is now garbage and is going to be rebuilt. This is done by writing another event to the Before stream — an Invalidated event.

A projection will now first receive an Invalidated for the stream. It is now the projection’s job to do any amount of clean up required to invalidate any information it has previously received for this stream. It is important to note that, although this is being brushed off, the logic for invalidation is often non-trivial and may even require storing more data than would otherwise be stored with the projection (no one said this would be easy).

After receiving the Invalidated event, the projection will then receive the entire new stream and simply process it same as it would any other new data. While seemingly simple and hassle-free, do not underestimate the amount of work and testing that goes into properly supporting an Invalidated event. For some projections, such as a list of customers, it is easy; just delete by ID. For others, it can become quite difficult, and you may be better off eating the inconsistency as discussed.

Still, Copy-Replace can be a powerful tool. It allows for many things you couldn’t do otherwise, including updating an event, but its power has a real cost in terms of complexity. It and its relatives are like the chemicals that go into cancer treatment: they may save you from one thing, but kill you in the process.

Thus far, though, we’ve only considered what happens if you completely, irreparably screw up within the boundaries of a stream. But what happens when you get your stream boundaries completely wrong and need to either split or merge multiple streams?

Stream Boundaries are Wrong

One of the worst situations people eventually run into with an Event Sourced system is that they modeled their streams incorrectly. This can happen for a variety of reasons. Among the most common is the requirements of the system having changed over time. While developers like to think of the system they are working on and the system they started with as one and the same, the required changes a system undergoes over time eventually make it an entirely different one at the end.

Other times, developers make mistakes in analysis. Something that seems one way at the beginning becomes different as deeper knowledge is gained. A quintessential example of this is in the logistics domain. The system manages the maintenance of trucks. Originally, Engine was modeled as part of a Truck. Later, as the system matures and brings in more use cases, the realization dawns that Engines are taken out of trucks and put into other trucks. Trucks and engines do not share a life cycle and should be in different streams, yet somehow find themselves in the same one.

Needing to split is not unique to Event Sourced systems. Document-based systems have an almost identical problem with this scenario. The existing documents need to be split to produce two documents.

Much like dealing with Copy-Replace, Split-Stream involves reading up from the first stream and writing down to two new ones. For example, you could read up from vehicle-1 and then write back to two new streams, vehicle-1-new and engine-7.

You could even do a transformation in the middle, just like with Copy-Replace, but do not do this. Applying a transformation comes with all the same problems as doing a transformation with Copy-Replace. How does a consumer handle the new events it will see? If you can simply avoid all transformations, then you can completely rely on idempotency in this case. If all you have done is move the events to different streams, they will remain the same events.

One place to be careful with a Split-Stream, though, is if the two new streams will share some events. In such a case, the same event gets written to both. This may or may not cause problems with idempotency, depending on the Event Store.

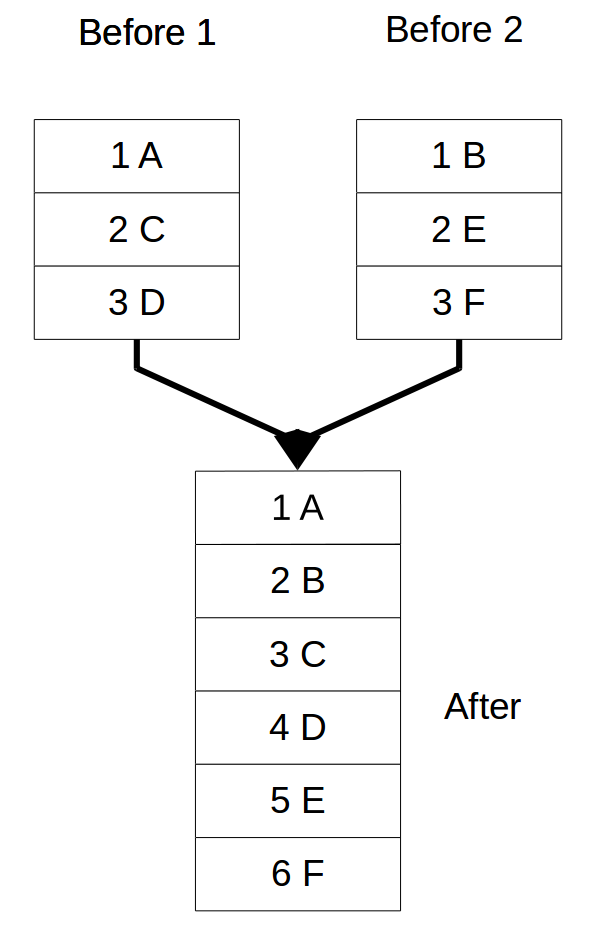

There is also a closely related problem, known as Join-Stream. It is the exact opposite of Split-Stream. Essentially, there are two current streams where one is desired. Obviously, it will be handled in an almost identical way.

Both of these are relatively easy to implement when stopping the system while they run. As they are only copying the same events and not translating, consumers simply need to be idempotent and everything will work without an issue. Alas, the luxury of being able to take the system down for a data migration is a rare one.

Changing Stream Boundaries on a Running System

Both Split-Stream and Join-Stream have similar problems of being run on a live system as Copy-Replace. They are simpler providing you do not introduce a transformation as part of the operation. If you want to transform, do it in two stages and your Split-Stream and Join-Stream will remain simple. That is, be sure to keep composition in mind.

In the exact same manner that the Copy-Replace required that both versions of software support both models, both Split-Stream and Join-Stream require both versions of software to support them too. If the current version does not support both models, you will need to do an intermediate release to ensure it does.

The strategy for determining which bit of logic to use is also similar to the Copy-Replace. For Split-Stream, first try to read the last event from the single stream. If it is not a StreamMovedTo event, then continue to read the stream as normal; otherwise, follow the appropriate link in the StreamMovedTo (note there are multiple ones here). For Join-Stream, the operation is almost identical (see Figure 5). Go to the original stream, check the last event if it is a StreamMovedTo, then follow the link; otherwise, continue with that stream.

As is also the case with Copy-Replace, it is very important to use ExpectedVersion when writing back to the stream. This is because the stream you are working on may get migrated while you are working on it. ExpectedVersion should be set to the last event read from the stream. If this step is forgotten, you may write an event to a stream after it is migrated and lose it in the process.

When dealing with Split-Stream and Join-Stream, it is very common to leave the original stream at least for a period of time. This is in case there was a problem with the operation or an auditor might want to make sure events were not added or lost along the way. It is also common to add a MigratedFrom {stream} event at the beginning of the migrated streams.

As long as the rule above about not performing a tranform while you are doing a split or join operation is respected, projections and other consumers will only need to be idempotent. Idempotency will catch all of the repeated events properly and you won’t need to worry about other edge cases, such as with Copy-Replace.

GetEventStore supports a slightly modified version of these patterns through its use of links. A link is a special type of event that acts as a pointer to another event. Using links, the process is a bit different, as well as better suited to auditing. Instead of copying the information on the Split-Stream or Join-Stream, you use links.

To start, block access to the original stream(s). This can be done by taking away write privileges. Next, write links to the stream(s) just as you would with a Copy-Replace. The new streams point back to the events in the original stream(s), but when you read from them they show up as if they were in the new stream(s). When an auditor looks at the system, they can see the original data and that the Split-Stream or Join-Stream occured. Also, since links are being appended, consumers will see them as links and not take action based upon them.

This chapter contains answers for what are probably the most complex problems in this book. Using these patterns, you can migrate 1M streams, including a selective split operation, on a 5TB database while your system is processing 2000 requests/second. This is likely not, however, your use case. In those others cases, there are other situational strategies for allowing the system to avoid downtime, not to mention these often horrifically complex scenarios.