Cheating

The patterns Copy-Replace, Stream-Split, and Join-Stream covered in the previous chapter are quite intense. Getting them to work on a running system is non-trivial. There will be times that they might need to be used. However, most of the time they can be avoided.

The patterns will work in any scenario. It does not matter whether it is a system that is doing 5000 transactions per second with TB of data or one doing seconds per transaction with 1 GB of data. They work in the same way.

There are, however, “cheats” that exist and which can be used in place of the more complicated patterns. Depending on the scenario, they may or may not apply, and the trade-offs associated with them may be better or worse than the those associated with the complexity of other patterns.

In this chapter, we will look at some of these “cheats” and consider where and when they might be applicable. Some relate to adding code complexity to avoid the need for versioning. Others look at different deployment options. If possible, you should generally favor a pattern from this chapter unless you are in a situation where you cannot use it for some reason.

Two Aggregates, One Stream

One of the most underrated patterns to avoid the need for a Stream-Split is to have two aggregates (states) being derived off of a single stream in the write model. It is strange that such a simple concept is often overlooked by teams who instead decide to go for the far more complex method of a Stream-Split. To be fair, the reason it gets overlooked is because many consider it to be hacky; it is breaking isolation, it is improper. At the end of the day, the job of a developer is to build working systems while mitgating risk. Code and architectural aesthetics lay a distant second.

There is nothing wrong with having two aggregates built off of the same stream.

Consider the previous example of the logistics company that has Engine currently modeled inside of Truck but then realizes that engines are actually taken out of trucks and placed into other trucks. Sometimes the truck is then discarded. This is a clear case of having two different life-cycles where a developer would really want to Stream-Split the Truck stream into a Truck stream and an Engine stream.

Another option is to not touch storage at all. Instead, only change the application model above it. In the application model, make Truck and Engine two separate things but allow them to be backed by the same stream. When loading an aggregate normally, events it does not understand are just ignored. So when Truck is replayed, Truck will listen to the events that it is interested in. When Engine is replayed, it will receive the events that it cares about.

Both instances will be able to be rebuilt from storage, and both instances can write to the stream. Ideally, they do not share any events in the stream but there are cases where they do. Try to keep things so that they do not share events. This will make it easier to do a Split-Stream operation later on, if wanted.

When writing, it is imperative that both use ExpectedVersion set to the last event they read. If they do not set ExpectedVersion, then there could be the other instance writing in an event that would disallow the event that they are currently writing. This is a classic example of operating on stale data. However, if they both use ExpectedVersion they will be assured the other instance has not updated the stream while a decision was made.

The setting of ExpectedVersion and having two aggregates can lead to more optimistic concurrency problems at runtime. If there is a lot of contention between the two aggregates, it may be best to Split-Stream. Under most circumstances, though, there is little contention either due to their separate life-cycles or due to a load overall system load.

Essentially what this pattern is doing is the exact same thing as a Split-Stream. It is just doing it dynamically at the application level as opposed to doing it at the storage level.

One Aggregate, Two Streams

A similar process can be applied to the problem of Join-Streams. When loading the aggregate, a join operation is used dynamically to combine two streams worth of events into a single stream that is then used for loading.

The join operation reads from both streams and orders events between them.

1 while(!stream1.IsEmpty() && !stream2.IsEmpty()) {

2 if(stream1.IsEmpty()) yield return stream2.Take();

3 if(stream2.IsEmpty()) yield return stream1.Take();

4 yield return Min(stream1,stream2);

5 }

This pseudocode will read from the two streams and provide a single stream with perfect ordering. It handles two streams but extrapolating this code to support N streams is not a difficult task. The aggregate or state is then built by consuming the single ordered stream generated.

The other side of the issue is handling the writing of an event. Which stream should it be written to? Most frameworks do not support the ability to specify a stream to write to, they are centered around stream per aggregate. If working without an existing framework or if you are writing your own it is a trivial issue. Instead of tracking Event, track something that wraps Event and also contains the stream that the Event applies to. Under most circumstances it will be stream per aggregate, but it supports the ability to have multiple streams backing an aggregate.

Another use case for having one aggregate backed by two streams is when faced with data privacy or retention policies. It is quite common that a system need to store information though some of it must be deleted after either a time period or a user request. This can be handled by creating two streams and having one aggregate running off of the join of the two streams. There could be User-000001-Public and User-000001-Private. User-000001 when loaded represents a join of these two streams. The User-000001-Private stream could have a policy associated to lose information or could be deleted leaving the public information in User-000001-Public.

Having multiple streams backing an aggregate is used much less often than multiple aggregates on the same stream. It feels more hacky and no frameworks that I know of support it. That said it can be a useful pattern when considered that the alternative would be to do a Join-Stream at the storage level.

Copy-Transform

Every pattern that has been looked at up until this point has focused on making a versioned change in the same environment. What if intead of working the same environment there were to be a new environment every time a change was made? This pattern has been heavily recommended in the great paper The Dark Side of Event Sourcing: Data Management.

One nice aspect of Event Sourced systems is that they are centered around the concept of a log. An Event Store is a distributed log. Because all operations are appended to this log many things become simple such as replication. To get all of the data out of an Event Store all that is needed is to start at the beginning of the log and read to the end of the log. To get near real-time data after this point just continue to follow the log as writes are appended to it.

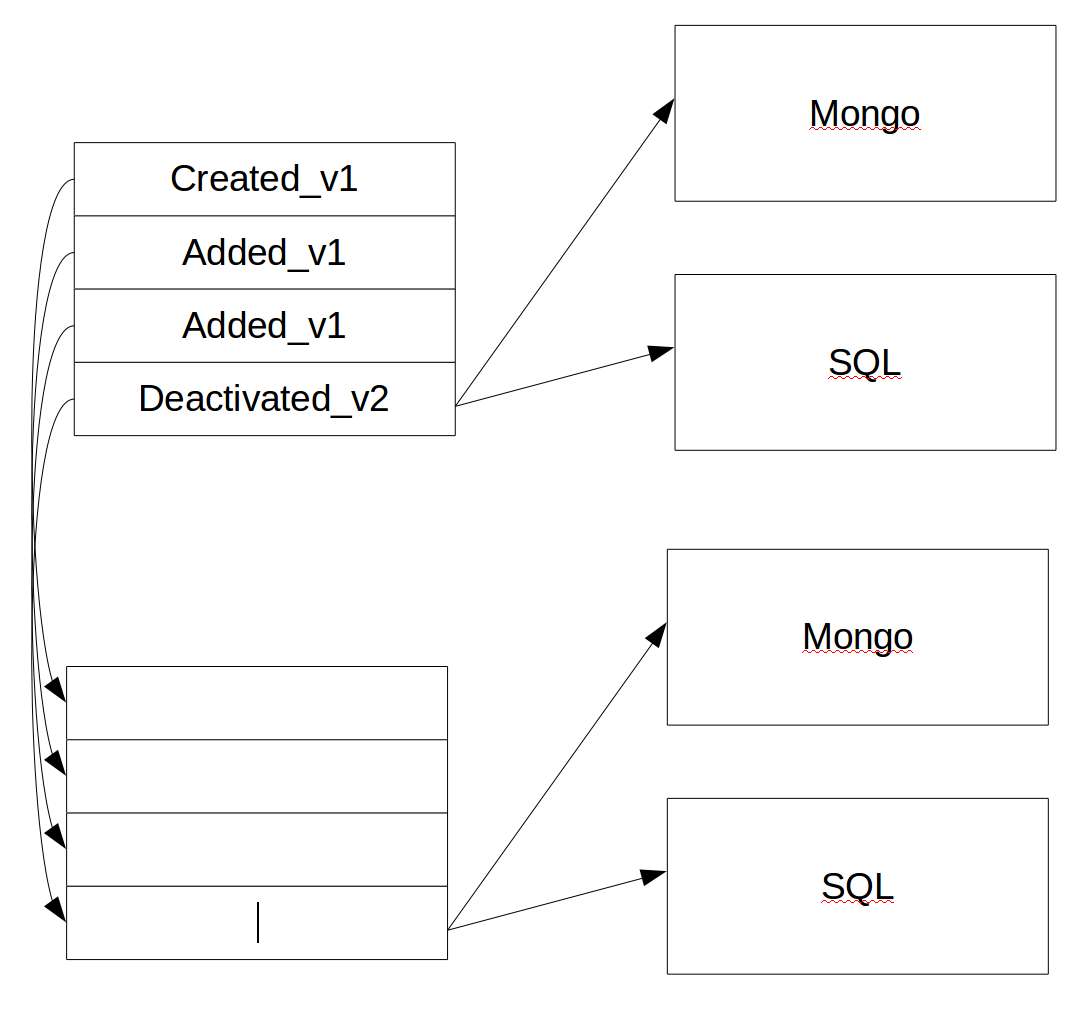

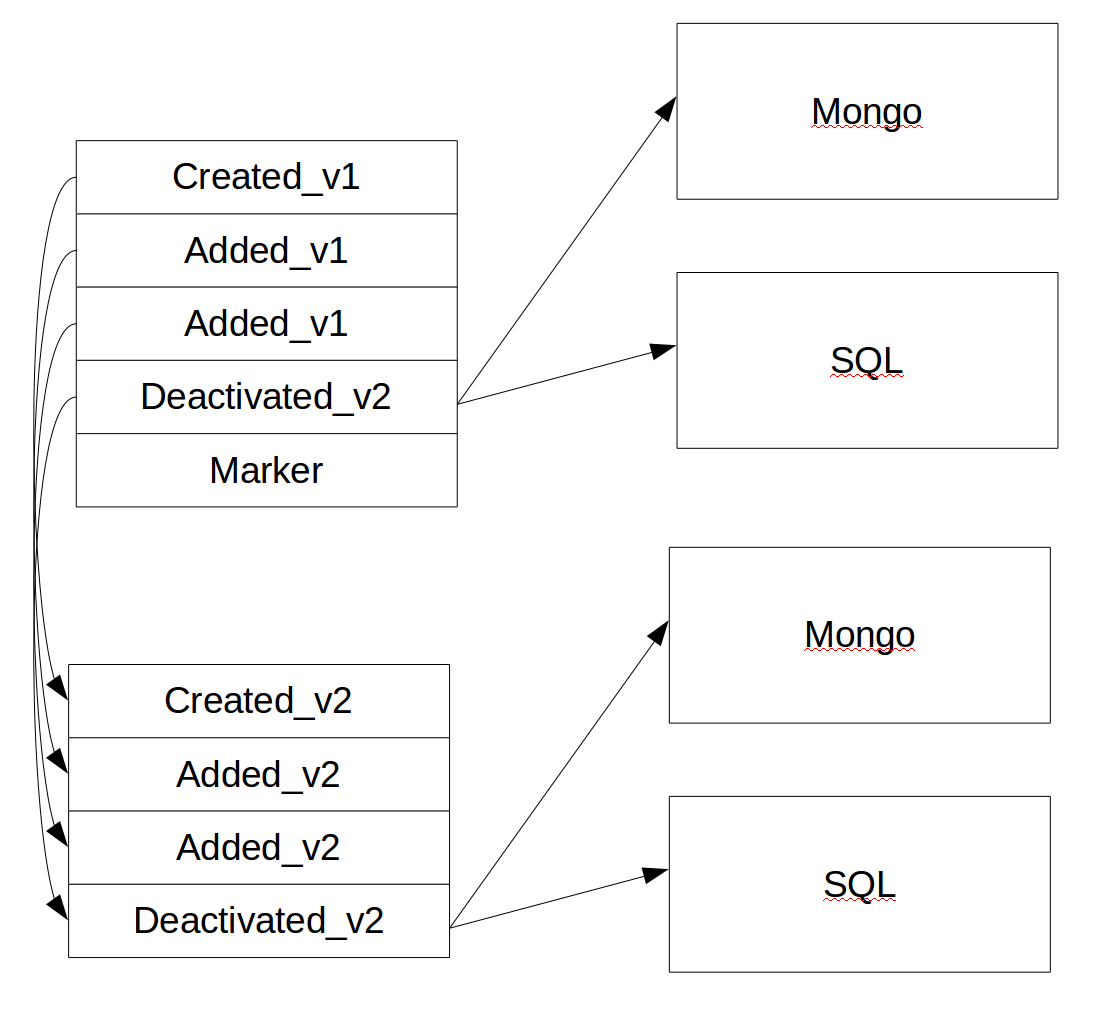

Figure 1 certainly seems much more complicated than the other patterns thus far. It is however in many ways simpler than them. Instead of migrating data in the Event Store for the new version of the application, the old system will be migrated to the new system. This migration process is the same process you would use if you were migrating a legacy system to a new system. Instead of versioning storage on each release treat each release as an entire new piece of software and migrate the old system to it.

Most developers have done a migration at some point in their career. One of the great things about doing a migration is that you don’t have to keep things the way those awful incompetent rascals before you did things; even if they were you. When doing a migration you can change however the old system worked into your new thing which is of course unicorns and rainbows, well until next year when you migrate off it again.

Instead of migrating system to system in Copy-Transform you migrate version to version. When doing this as in doing a Copy-Replace there is an opportunity to put a transformation in the process. Another way of thinking about Copy-Transform is Copy-Replace but on the entire Event Store not just on a stream.

In this transformation step, just like in Copy-Replace, anything can be done. Want to rename and event? Split one event into two? Join streams? The world is your oyster as you are writing a migration. The migration starts on the first event of the old system and goes forward until it is caught up. Only the old system is accepting writes so the migrated system can continue to follow it.

The new system not only has its own Event Store, it also has all of its own projections to read models hooked to it. It is an entire new system. As the data enters the Event Store it is then pushed out to the projections that update their read models. The Event Store may catch up before the projections. It is very important to monitor the projections so you know when they are caught up. Once they are caught up the system as a whole can do a BigFlip.

To do a BigFlip the new system will tell the Event Store of the old system that it should stop accepting writes, drain all the writes that happened before. Wait a short period of time. Then direct all traffic to the new system. This process generally takes only a few hundred milliseconds. After the new system has all load pointed to it and the old system is discardable.

A common practice is to issue a special command to the old system at this point that will write a marker event. This marker event can be used to identify when the new system has caught up with the old system and the load balancer, etc., can be updated to point all traffic at the new system. This is a better mechanism than waiting for a few seconds, as it signals exactly when the new system is caught up and avoids the possibility of losing events during the migration due to a race condition.

It is important to not that because this is a full migration all of the issues dealing with projections from Copy-Replace go away. Every projection is rebuilt from scratch as part of the migration.

Overall this is a nice way of handling an upgrade. It does however have a few limitations. If the dataset size is 50 GB the full Copy-Transform is not an issue. It might take an hour or three but this is reasonable. I personally know of an EventStore instance in production that is 10TB, “We released this morning it should be ready in a week or two.”. Another place it may not work well is when you have a scaled or distributed read side. If I have 100 geographically distributed read models it might be quite difficult to make this type of migration work seemlessly.

Another disadvantage of Copy-Transform is that it requires double the hardware. The new system is a full new system. This is however much less of an issue with modern cloud based architectures.

If you are not facing these limitations a Copy-Transform is a reasonable strategy. It removes most of the pain of trying to version a live running system by falling back to a BigFlip. Conceptually this is simpler that trying to upgrade a live running system. It is also a good option to consider

Versioning Bankrupty

Versioning Bankrupty is a specialized form of Copy-Transform. It was mentioned in the Basic Versioning chapter that everything you need to know about Event Sourcing you can learn by asking an accountant.

So how do accountants handle data over long periods of time?

They don’t.

Most accountants deal with a period called year end. At this time the books are closed, the accounts are all made to balance a new year is started. When starting a new year the accountant does not bring over all of the transactions from the previous year, they bring over the initial balances of the accounts for the new year.

One of the most common questions in regard to Event Sourced systems is “How do I migrate off of my old RDBMS system to an Event Sourced system?”. There are two common ways. The first is to try to reverse engineer the entire transaction history of given concepts from the old system to recreate a full event history in the new system. This can work quite well but runs into issues in that it can be a lot of work and that it may be impossible.

The second way of migrating is to bring over an “Initialized” event that initializing the aggregate/concept to a known starting point. As an example in the accounting example an AccountInitialized event would be brought over that included the initial balance of the account as well as any associated information like the name of the account holder.

In doing a system migration it is common to use both mechanisms chosen on an aggregate by aggregate basis. For some an “Initialized” event may be brought over and for others a history can be brought over. The choice between them is largely how much effort do I want to put in compared to what value is there in having the history.

Remember that a Copy-Transform is a migration! Just from one version of your system to the next

When migrating from your own system that is already Event Sourced it should be relatively easy to reverse engineer your history since it is well your history. In this circumstance there may be another reason to bring over “Initialized” events. They allow you to truncate your history at a given point! Imagine there is a mess that has been caused on a set of streams over time. You can summarize that mess and replace it with an “Initialized” event as part of your migration in Copy-Transform.

Businesses also often have time periods such as year end built into their domain. If you want to change the accounting system in a company it will almost certainly happen at year end, not at any other time during the year. This can also be a good time to execute a bankruptcy. To execute the bankrupty, run the migration then instead of deleting your old store and read models such as in Copy-Transform, keep them. Label them for that time period. They are now there for reporting purposes if needed.

I once worked at a company that did this to their accounting system every year regardless of if they were changing or not. In the accounting office there were 10 accounting systems. Nine were marked by their year and were read-only as only the current one could be changed. They even ran them on separate labeled machines such as “ACCT1994”. They declared bankruptcy every year even if they were not changing software and migrated into the new accounting system.

Versioning Bankruptcy can also be used as We-Have-Too-Much-Data Bankruptcy. If large amounts of data are coming into a system a yearly or shorter time frame where the old data is migrated to the new with “Initialized” events can allow for the archiving of the old data allowing for the current system to run with much smaller datasets.

On an algorithmic trading system I worked on we had a daily timeframe. The market open and closed daily. We would at the beginning of the day bring over all of our open positions, account information, and look up data. Data would come from the market for the day as well as our own data on positions etc. At the end we would go through an end of day process. One great feature of this is that a day’s log was totally self-contained and can be archived. Later to understand June 2, 2006 you can load only the log of June 2, 2006 and everything is needed.

There is also a downside to this style of archiving for either versioning or space needs. It can become quite difficult to analyze historical data outside of a single time period. Some systems tend to be based on periods, some based on continuous information. This pattern does not work well in continuous systems. Running a projection that covered two years worth of information from the accounting system was a real pain. With the algorithmic trading system, running a projection that spanned two weeks was a pain. As we did it on a regular basis, a solution was built for it. However, it was complex and took a good amount of time to implement.