Typical process overview

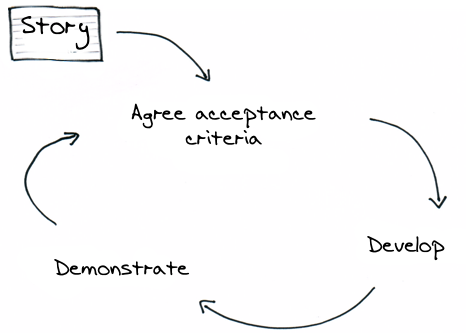

The story delivery lifecycle

A typical agile process used by many teams today revolves around the following steps often referred to as the story delivery lifecycle. The steps act as a guide to ensuring you’re working on incremental value, to highligh problems or misunderstanding early and give you the chance to adjust.

| Story delivery lifecycle |

|---|

| 1. Pick a story |

| 2. Agree acceptance criteria |

| 3. Develop functionality |

| 4. Demonstrate and sign off |

| 6. Repeat |

Let’s go through these steps in more detail.

Pick a story

Picking the next story to play should be as simple as taking the next highest priority story from the list of options. Creating the option list or backlog is a little more interesting. Ideally, there should be ongoing work to identify concepts that, if realised, would help achieve business goals (cash). In the corporate environment, it’s typically the responsibility of the business analysts to come up with candidate features for a project.

It would usually fall to the iteration planning of a Scrum process to move a set of stories from the backlog to the planned iteration. The team would then attempt to deliver these stories when starting the iteration. In a Kanban process, the backlog becomes the pool of candidate stories that are drawn from at any given time; it becomes the input queue for subsequent activities (such as agreeing acceptance criteria). In both cases, it helps if when picking up a story to work on, there is a good understanding of the business objective it realises. In other words, what’s the real value this story would deliver.

The next step is to express this value in the form of acceptance criteria.

Agree acceptance criteria

It may be that the story you pick up lacks sufficient detail to answer the question “how do we know it’s done?”. To figure this out, you define the acceptance criteria and in doing so, better understand what’s really needed. You might explore example scenarios, edge cases and outcomes to help. The idea here is to describe the requirements not in terms of a series of instructions to follow (a traditional test script) but as an english description of the business goals. When you can prove these have been met, you know the story is done.

When you describe the high level business scenarios like this, you implicitly create a specification accessible to business and technical staff. You’re not concerned with the details of how things will be implemented. It’s a chance to focus on the business intent and make sure everyone involved understands what’s expected, the terminology and the business context.

This is best done with the business or customer. Get together and make sure everyone has a common understanding of what’s needed. Expect lots of discussion about the specifics and come up with concrete examples and scenarios. What questions, if answered, will convince the customer that the system is behaving as they specified?

Once you’ve written the criteria down, the next step is to formally agree them with interested parties. We’ll brush over how best to physically record the criteria but aim to have them in a format that will help you later when it comes to converting them into executable tests. You might record these on a Wiki, HTML pages stored with the source code or just on the back of the story card. The point is that after this step, everyone involved has agreed that the list of criteria is a reasonable effort at documenting the intent. It’s not set in stone but it captures the current understanding.

Remember that all this is done before writing any production code.

Tick off these items as you go through the agree acceptance criteria phase.

- Business analysis has been undertaken

- Developers understand the business background, context and goals for a story

- There is no ambiguity about business terms and everyone agrees on their definition

- Acceptance criteria have been discussed and documented

- Agreement has been reached on the acceptance criteria

Develop

As well as implementing the underlying features, the developers should be converting acceptance criteria into runnable tests during this phase. It may be that tests are written early in the development phase, before any real work has gone on and they’ll continue fail until the story is completed. Or, it may be that the majority of development is undertaken before work on implementing the acceptance tests start.

Which approach you choose has interesting affects on developer testing. For example, if the coarse grained acceptance test is left until the end, you might focus on unit tests and use TDD to drive out design. TDD in this sense is a tool to aid design. When it comes to implementing the acceptance test, there’ll be very little left unknown. It can be a bit like test-confirm where you back fill the details to get a green test.

In contrast, when developers start with failing acceptance tests, the focus shifts. Acceptance tests are used to drive out coarse grained behaviour like unit tests drive out low level design choices. The acceptance tests themselves may change more frequently with more discussion with the customer taking place. The emphasis is on requirements (the story) and in this sense, the tests become more of a tool to help build requirements. This ATDD approach puts acceptance tests in the position that TDD puts unit tests in; at the beginning.

There’s an argument in claiming that unit tests may not even be needed with sufficient acceptance tests in place. The meaning of “sufficient” here is open for debate. If the edge cases that unit tests would have picked up are unlikely to materialise and if the cost of fixing these once in production is low, then why test upfront? Especially, if this upfront cost affects the time to delivery (and by extension your profits). To put the argument in the extreme, you could say that you’re not really doing ATDD if you’re still writing unit tests.

Unit tests give confidence in the low level but if the overall system behaviour doesn’t deliver the business proposition, you still won’t be making any money. The right answer to the wrong question is still the wrong answer. Acceptance tests should demonstrate the business proposition and so have monetary value whereas unit tests have design value.

Your team’s experiences and preferences will influence which approach you choose. Sometimes, the two compliment each other, other times they get in each others way and duplicate effort. Judicious testing takes care and practice.

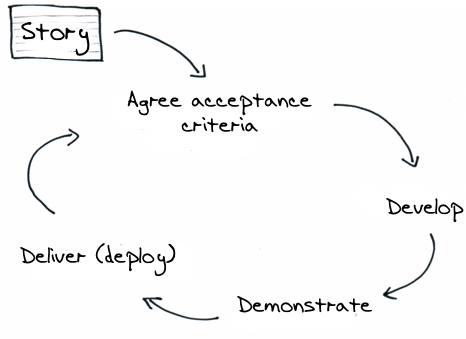

Demonstrate

This step is about proving to customers that their requirements have been realised. It’s about giving them confidence. You can do this in whatever way works best for your team. A common approach is to run through a manual demo and walk through the passing acceptance tests huddled around a desk.

After the demo, if everyone agrees the implementation does what’s expected, the story can be marked as done and you can go round the cycle again with the next story. If there is disagreement or if new issues come up, it’s ok to go round the loop again with the same story. Agree, develop, demo and deliver.

If you discover incremental improvements could be made, you might create a new story and go round the loop with that. This is different from going through the cycle again with the same story which would be more iterative. Think of it like incrementally adding value rather than iteratively building value piece by piece before finally releasing. It’s like tweaking an already selling product in order to sell more (incremental improvement) as apposed to building a product out until the point it can start to sell (iterating).

A note on manual testing

If you’re lucky, there’s plenty of people on hand willing to perform some exploratory testing. This doesn’t have to wait until the end of an iteration, it can start as soon as a story is stable enough to test. Usually this would be when the story is finished and acceptance tests are passing. It’s useful to have a stable deployment environment for this.

Acceptance testing doesn’t negate the need for manual, exploratory style testing. Lisa Crispin calls this kind of testing critiquing the product. Some critiquing can be achieved using acceptance testing whilst more may require a manual approach or specialist tools. We’ll look more at this later when we talk about Brian Marick’s testing matrix and Crispin’s elaboration.

To some degree, acceptance test suites address the need for regression testing. That is to say that derivation of behaviour hasn’t been introduced if the acceptance tests still pass.

Deliver

When a story is finished, you may go round the loop again with a new story or choose to deliver the functionality directly to your production environment. This often gets less emphasis because it usually happens when multiple stories are batched up and deployed together, for example, at the end of an iteration. It’s actually a crucial step though as its only after this point that potential story value can be realised.

It can be incorporated into the story delivery lifecycle when continuous delivery ideas are applied with the aim to deploy individual stories as they’re ready. It’s a fairly sophisticated position to take and requires careful crafting of stories so that they add demonstrable value. It also implies a well groomed and automated build and deployment procedure.

The expanded story delivery lifecycle