Problems acceptance testing can fix

The typical process described previously isn’t a panacea; it’s always worth considering what problems you’re actually facing before adopting any new process. Acceptance testing isn’t always appropriate so it’s worth considering your circumstances and what problems acceptance testing can fix.

Communication barriers

The typical process described in Part 1 can be useful in encouraging communication. There’s a formal vehicle (the acceptance test artifacts) that must be created and agreed and it puts checkpoints in place to emphasise the agreement (for example, using stickers as sign-off).

When not using this approach, if you find that requirements are being misunderstood or not delivered as the customer intended, forcing formal communication like this may be useful. It’s a technique that may help overcome underlying communication problems and if there’s already good communication, it can be used to document the dialogue.

It doesn’t mean that the story delivery lifecycle is a substitute for spontaneous and continued communication. It can be tempting to lean on formal mechanisms like this as the only communication mechanism but this can lead to its own problems (discussed in the Problems acceptance testing can cause) section.

The process is intended to encourage communication not to stifle it. You create artifacts that can be shared, referred back to and you demonstrate these executable artifacts to the stakeholders. It doesn’t preclude speaking to them whenever you feel like it. If you discover new insight, you’re free to adjust the acceptance criteria and tests; to go round the loop again.

Lack of shared memory

The acceptance tests document a shared (and agreed) understanding of features. As time goes on, its easy to forget how a particular feature is supposed to behave. If acceptance tests are in a customer friendly format, they form reference documentation that will always be accurate; a live record of the system’s behaviour.

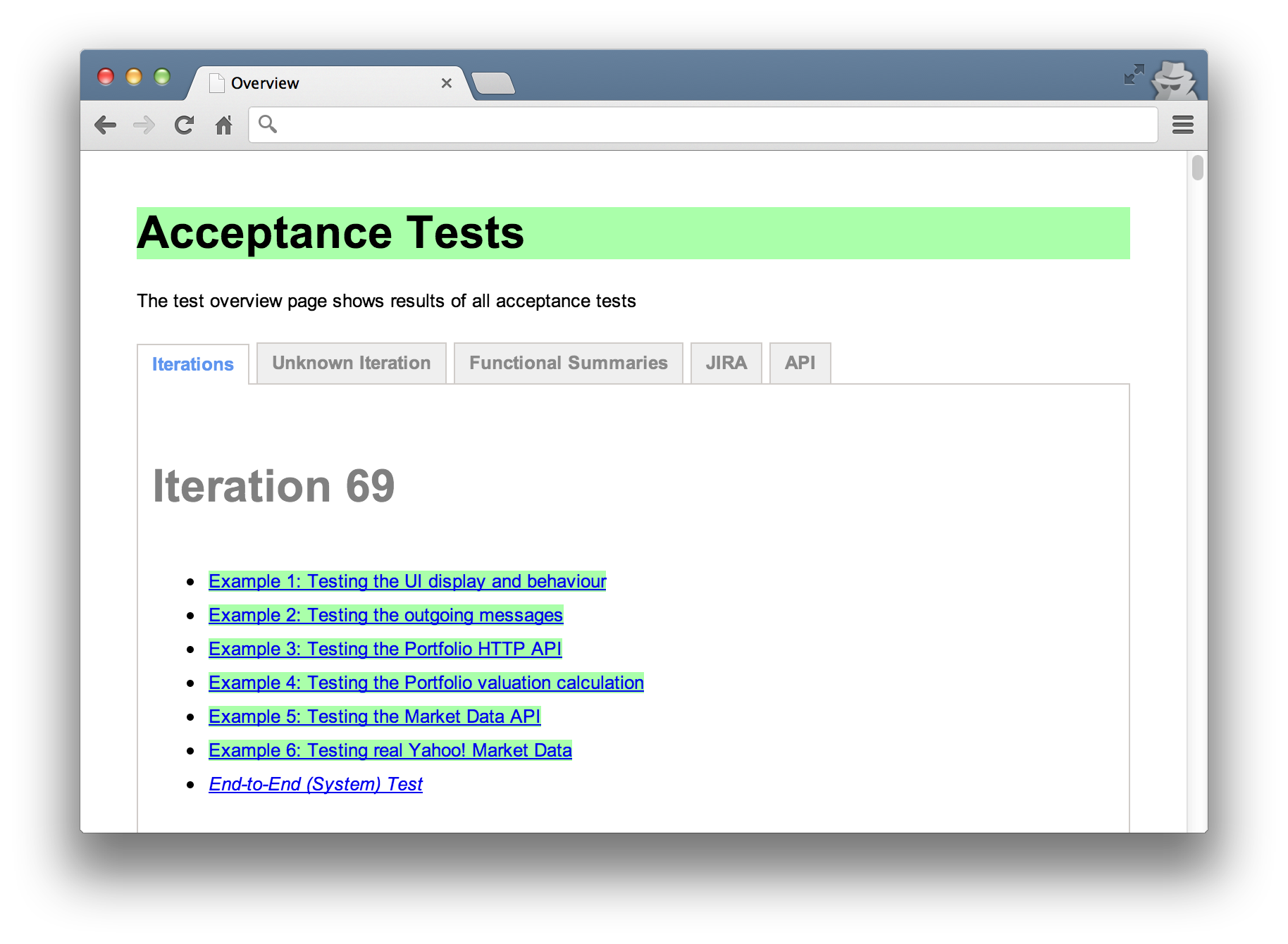

Tools like Yatspec, Concordion and Concordion.NET emphasise this aspect and can be used to create HTML documentation to share. You can organise this however you like. You might show features grouped by area, iteration and even use it to document a low level API.

An example of a Concordion HTML overview. Tests are grouped under tabs and users can drill down into the detail.

Lack of collective understanding of requirements

It’s very difficult to appreciate what a customer really wants from broken fragments of conversations or email trails. There’s a lot of room for ambiguity. By slowing down and carefully going over examples and collaboratively creating acceptance criteria, the hope is that any misunderstanding will come up early and be addressed. It’s often the case that specific questions about error and edge cases will surface and cause the customer to think harder about their requirements.

Writing acceptance criteria down in the form of tests isn’t the only tool available here. Conversation, previously generated documentation, spreadsheets, flow diagrams, gorilla diagramming, anything and everything all feed into the process. Acceptance tests just document the understanding.

Blurring the “what” with the “how”

When it comes to business goals it’s the “what” that’s important and not the “how”. At least, when it comes to making money, focusing on the goal is very different than focusing on the details of how to achieve it. If these ideas are blurred, all kinds of problems can arise.

Acceptance testing aims to help separate goals from implementation. Goals are defined as acceptance criteria and the development team are left to implement and prove that the criteria have been met in whatever way they feel is appropriate. The criteria describe the “what” and proving this is more important than “how”. In practice, technology choice can undermine this aspiration. For example, if a testing technology exposes too much detail about the system design or criteria are written in technical terms (rather than business terms), the business will acclimatise to the detail and may miss the high level objectives. Defining technically oriented stories (with little real value) can be another example of blurring the lines.

Ambiguous language

Often customers and developers have their own language for things. When there’s ambiguity in terminology, misunderstanding or confusion is bound to arise.

For example, in finance, the noun trade can mean very different things to different departments. The direction of a transaction, buy or sell can be inverted depending on what side of the fence you sit on. Getting this right in your system is obviously going to be important.

Not assuming anything and defining terms clearly in acceptance tests can be a good way to ensure some consistency. This takes discipline though and relies on people bringing up inconsistent use of terminology as it happens. Individuals may also need to be brave and ask the “obvious” questions.

Common language is formalised in an acceptance test, crystallising it’s definition. The goal here is to achieve an ubiquitous language.

Lack of structure and direction

Iterative development favours planning; iterations are planned ahead of time. The stories to deliver are fixed at the start of an iteration. Although the iterations are short, it still imposes rigidity. The balance is in offering the delivery team stability as well as being responsive to changes in business priorities.

By stability, I mean that the goal for the next week or so is well known and the team know where they’re heading and why. They’re free from process distraction. With it, scope creep and fire fighting can be kept to a minimum and the team is free to focus on multiple, small, achievable deliveries.

Having an established process like the story delivery lifecycle can give structure to delivery and contribute to sustainable pace. Such a process certainly offers clear boundaries and check points. Crossing them helps establish a rhythm or cadence and gives the team a chance to celebrate what they’ve achieved. People know where they stand.

Compare this to the prospect of working on a large multi-feature chunk of work with no clear goals and no end in sight. Morale and discipline suffer. Edward Deming talked about this when discussing the Seven Deadly Diseases to effective management. He described what he considered the most serious barriers to business. Specifically, a lack of structure and direction implies a lack of constancy of purpose to plan and so encourages short term thinking.

This point may well be more about decomposition than adopting an acceptance testing process. People just handle small tasks better. There is a personal psychology aspect but there’s also advantages for the business in dealing in small features. It reduces risk and allows for quicker change of direction.

Team engagement

The story delivery cycle can give the entire team (developers, testers and the business) the opportunity to understand the motivations and contribute to the planning and execution of solutions. Along with creating the rhythm or cadence already mentioned, it can help galvanise the team around small, frequent delivery milestones. Compare this to teams that actively encourage “shelf stacking”, where developers are spoon fed technical tasks with no real engagement and expected to simply stack the shelves without understanding why.