The Story of Developing a Clean App by Example

Part 1: Bootstrapping – Setting Up the Project, Core Data, and Unit Tests

Swift is still pretty new. Since it’s so new, it’s likely you haven’t had a chance to use it seriously. After all, investing in a hip new language is pretty risky: it takes time and might not lead you anywhere.

With Swift, it’s a safe bet to stay a Cocoa developer in the future. Apple pushes the language forward, so there’s a lot of momentum already. Swift is not in the same situation Java was in during the late 1990’s.

Initially, you may not know if errors happen because you can’t use Swift properly, or if it’s an actual implementation problem. I guess having existing code to port makes it easier to take Swift for a test drive. Without that luxury, you’ll have to learn faster.

That’s why we’re going to start with a natural approach to learning Swift and getting an application up and running.

This part of the book is not about designing and crafting the application in a “clean” manner. There’s no up-front design. This part is about understanding the new ecosystem of Swift and how it integrates with Xcode and existing Cocoa frameworks. It’s an exploratory part: I think you’ll be able to follow along with the resistance I encountered and how I thought and coded my way out of dead-ends better in this style.

I dedicate this part to making the switch to Swift and getting everything to run, including:

- Get Core Data and related tests running

- Prepare the user interface in its own layer

- Have tests in place for the app’s domain

In the second part, I’ll cover the actual application’s functionality. We’ll be going to explore a lot of architectural patterns in-depth there.

This part is mostly made up of longer notes or journal entries. They aren’t meant to tell a coherent story. They are meant to provide a view over my shoulder, include details and background information so you can follow along easily.

Think of this part as a log book to follow the path to adopting Swift. You may want to skim most of this part if you’re comfortable with Swift, XCTest, and Core Data already.

Functional Testing Helps Transition to Adding Real Features

I’m pretty confident the view does what it should do. It’s all just basic stuff, although it took enough trial & error to reach this point. (I am talking about you, explicit Cocoa Bindings which break the view’s behavior!)

I am curious if the app will work, though. This is only natural. Developers want to have a running prototype as early as possible. I’m no exception. Unit tests can help to get feedback that algorithms work. But you won’t know if the app executes and performs anything at all until you run it. There are two steps I could take at this point to quench my curiosity.

First, I could use more unit tests to verify that view model updates result in NSOutlineView updates. These updates should also be visible when I run the app, but the unit tests won’t give visual feedback. Still, I would verify that the controller logic works. Since the data doesn’t change in the background but depend on me clicking on widgets, I’m eager to see Cocoa Bindings in action. Then again, I’ve already witnessed Cocoa Bindings in another project. It felt like magic when the label updated to a new value that the component received after a couple of idle time automatically. Key-Value Observing is doing a lot of the hard work here. I can assure you that the Cocoa Bindings are set up correctly; in fact, the binding tests verify that the setup is working. Seeing the changes in the running app equals a manual integration test – that is testing Apple’s internal frameworks to do their job properly. That doesn’t make any sense. I would like to see it in action, but it won’t provide any useful information.

Second, I could add functional tests to the test harness. And this is what I’ll do: in a fashion you usually find with Behavior-Driven Development (as opposed to Test-Driven Development, where you start at the innermost unit level), I’ll add a failing test which will need the whole app to work together in order to pass. It’s a test which is going to be failing for quite a while. It’s an automated integration test that exercises various layers of the app at once.

In the past I wrote failing functional tests for web applications only because they would drive out the REST API or user interaction pretty well. I haven’t tried this for iOS or Mac applications, yet. So let’s do this.

If you work by yourself, I think it’s okay to check in your code with a failing test as long as it’s guiding development. Don’t check in failing unit tests just because you can’t figure out how to fix the problem immediately. Everything goes as long as you don’t push the changes to a remote repository. Until that point, you can always alter the commit history.

Having a failing functional test at all may not be okay with your team mates, though. After all, your versioning system should always be in a valid state, ready to build and to pass continuous deployment. Better not check in the failing test itself, then, or work on a local branch exclusively until you rebase your commit history when your feature is ready.

The bad thing about functional tests or integration tests is this: if all you had were functional tests, you’d have to write a ton of them. With every condition, with every fork in the path of execution, the amount of functional tests to write grows by a factor of 2. Functional tests grow exponentially. That’s bad.

So don’t rely too much on them. Unit tests are the way to go.

And make sure you watch J. B. Rainsberger’s “Integrated Tests are a Scam” some day soon. It’s really worth it.

That being said, let’s create a functional test to learn how things work together and guide development.

First Attempt at Capturing the Expected Outcome

I want to go from user interface actions all down to Core Data. That’s a first step. This is the test I came up with:

1 func testAddFirstBox_CreatesBoxRecord() {

2 // Precondition

3 XCTAssertEqual(repository.count(), 0, "repo starts empty")

4

5 // When

6 viewController.addBox(self)

7

8 // Then

9 XCTAssertEqual(repository.count(), 1, "stores box record")

10 XCTAssertEqual(allBoxes().first?.title, "New Box")

11 }

There’s room for improvement: I expect that there’s a record with a given BoxId afterwards, and that the view model contains a BoxNode with the same identifier. This is how the view, domain, and Core Data stay in sync. But the naive attempt at querying the NSTreeController is hideous:

viewController.itemsController.arrangedObjects.childNodes!!.first.boxId

I rather defer such tests until later to avoid these train wreck-calls and stick with the basic test from above that at least indicates the count() did change, even though I don’t know if the correct entity was inserted at this point.

Making Optionals-based Tests Useful

On a side note, I think Swift’s optionals are making some tests weird. With modern Swift, optional chaining and XCTAssertEqual play together nicely:

XCTAssertEqual(allBoxes().first?.title, "New Box")

Sometimes, you need to unwrap an optional, though. Force-unwrapping nil results in a runtime error which we want to avoid during tests because it interrupts execution of the whole test suite. A failure is preferable.

if let box = allBoxes().first {

XCTAssertEqual(box.title, "New Box")

} else {

XTCFail("expected 1 or more boxes")

}

Imagine allBoxes() returned an optional; then the complexity of the test would increase a lot:

if let boxes = allBoxes() {

if let box: ManagedBox = allBoxes().first {

XCTAssertEqual(box.title, "New Box")

} else {

XCTFail("no boxes found")

}

} else {

XCTFail("boxes request invalid")

}

When you work with collections, instead of nil, return an empty array. This makes the result much more predictable for the client. Here’s the updated version:

1 func allBoxes() -> [ManagedBox] {

2 let request = NSFetchRequest(entityName: ManagedBox.entityName())

3 let results: [AnyObject]

4

5 do {

6 try results = context.fetch(request)

7 } catch {

8 XCTFail("fetching all boxes failed")

9 return []

10 }

11

12 guard let boxes = results as? [ManagedBox] else {

13 return []

14 }

15

16 return boxes

17 }

If optional chaining doesn’t work for you for some reason, make it a two-step assertion instead:

let box: ManagedBox = allBoxes().first

XCTAssertNotNil(box)

if let box = box {

XCTAssertEqual(box.title, "New Box")

}

If the value is nil, the first assertion will fail and the test case will be marked as a failing test. You can come back to it and fix it. No breaking runtime errors required!

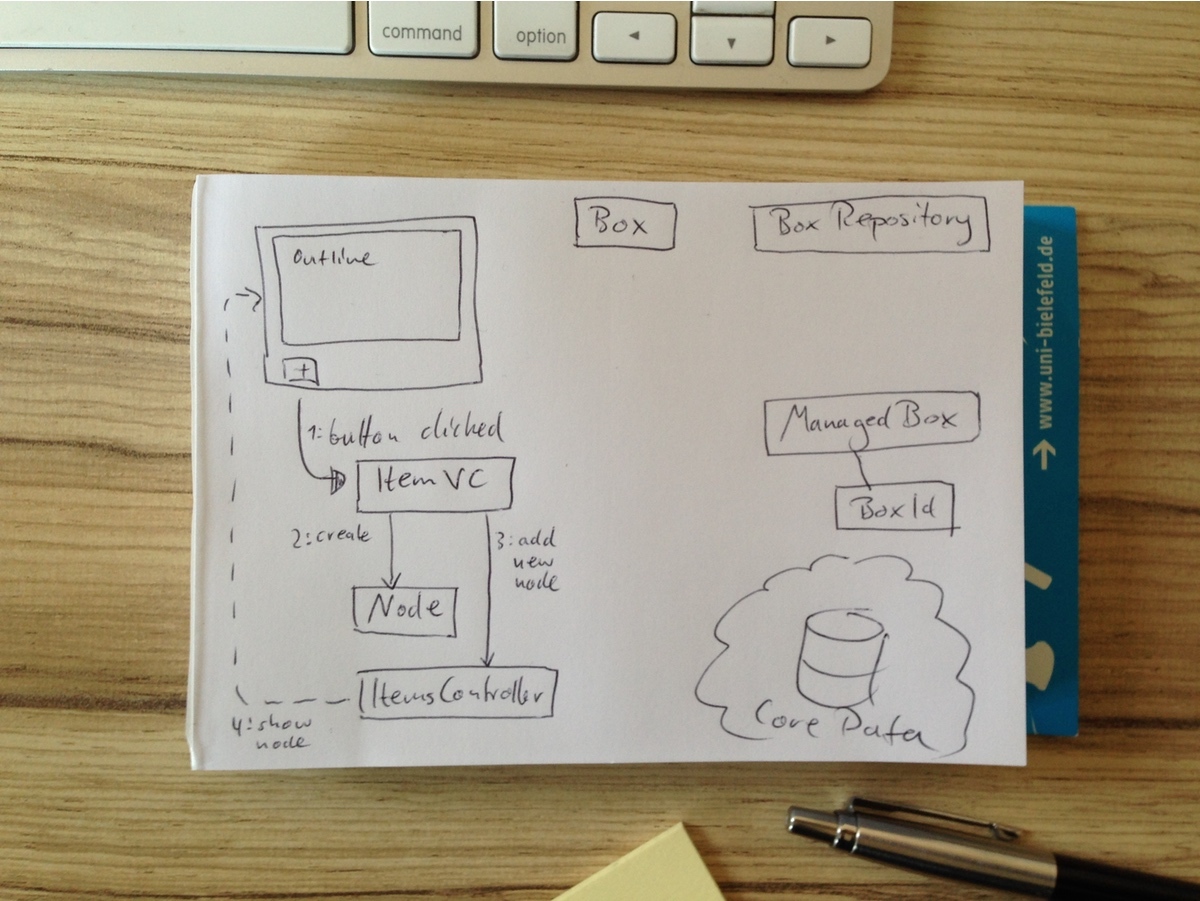

Wire-Framing the Path to “Green”

Now this integration test fails, of course. In broad strokes, this is what’s left to do to connect the dots and make it pass:

- I have to make a repository available to the view. I’ll do this via Application Services.

- I have to add an actual Application Service layer. Remember, this is the client of the domain.

- The Application Service will issue saving

Boxes andItems without knowing about Core Data. - I need a service provider of sorts. Something somewhere has to tell the rest of the application that

CoreDataBoxRepository(from Infrastructure) is the default implementation of theBoxRepositoryprotocol (from the Domain). The process of setting this up takes place in the application delegate, but there’s a globalServiceLocatorsingleton missing to do the actual look-up. - I may need to replace the

ServiceLocator’s objects with test doubles.

The ServiceLocator can look like this:

1 open class ServiceLocator {

2 open static let sharedInstance = ServiceLocator()

3

4 // MARK: Configuration

5

6 fileprivate var managedObjectContext: NSManagedObjectContext?

7

8 public func setManagedObjectContext(_ managedObjectContext: NSManagedObj\

9 ectContext) {

10 precondition(self.managedObjectContext == nil,

11 "managedObjectContext can be set up only once")

12

13 self.managedObjectContext = managedObjectContext

14 }

15

16 // MARK: Dependencies

17

18 public class func boxRepository() -> BoxRepository {

19 return sharedInstance.boxRepository()

20 }

21

22 // Override this during tests:

23 open func boxRepository() -> BoxRepository {

24 guard let managedObjectContext = self.managedObjectContext

25 else { preconditionFailure("managedObjectContext must be set up"\

26 ) }

27

28 return CoreDataBoxRepository(managedObjectContext: managedObjectCont\

29 ext)

30 }

31 }

It’s not very sophisticated, but it is enough to decouple the layers. An Application Service could now perform insertions like this:

1 public func provisionBox() -> BoxId {

2 let repository = ServiceLocator.boxRepository()

3 let boxId = repository.nextId()

4 let box = Box(boxId: boxId, title: "A Default Title")

5

6 repository.addBox(box)

7

8 return boxId

9 }

This is not a command-only method because it returns a value. Instead of returning the new ID so the view can add it to the node, the service will be responsible for actually adding the node to the view. That’d be the first major refactoring.1

It’s about time to leave the early set-up phase and enter Part II, where I’m going to deal with all these details and add the missing functionality.

Part 2: Sending Messages Inside of the App

I tried to prepare all of the app’s components so far in isolation and not worry much about the integration. In other words, running the app will show that things don’t seem to work. The basic structure is in place, but there’s virtually no action. That’s changing in this part.

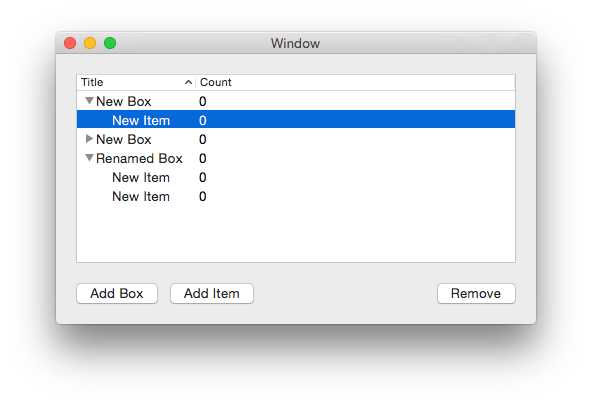

The app window is going to look like this:

At the moment, the state of the app is the following:

- The user interface is operational but doesn’t persist data. The

ItemViewControllerreacts to button presses and creates node objects. - The Core Data part of infrastructure seems to work fine according to the tests but doesn’t receive any commands, yet.

- The domain is particularly boring. It has no behavior at all. Until now, the whole demo application is centered around getting user input to the data store. This will not change until the next part. It’s nonsensical to work this way of course when the domain should be the very key component of the application.

- There’s no event handling at all, as in “User adds a Box to the list”. There’s no layer between user interface and domain.

This part will focus on the integration and various methods of passing messages between components of the app. When I figured out the structure of the app in the last sections, now I worry more about designing the processing of information and performang actions. There are a few attractive options to consider:

- Cocoa’s classic delegate pattern to obtain objects (“data source”) and handle interactions (“delegate”)

- Ports & Adapters-style command-only interfaces, adhering to CQRS2

- Leveraging Domain Events (since there’s no domain worth speaking of, we’ll defer exploring that option to part 3)

We’ll look at all of these in detail.

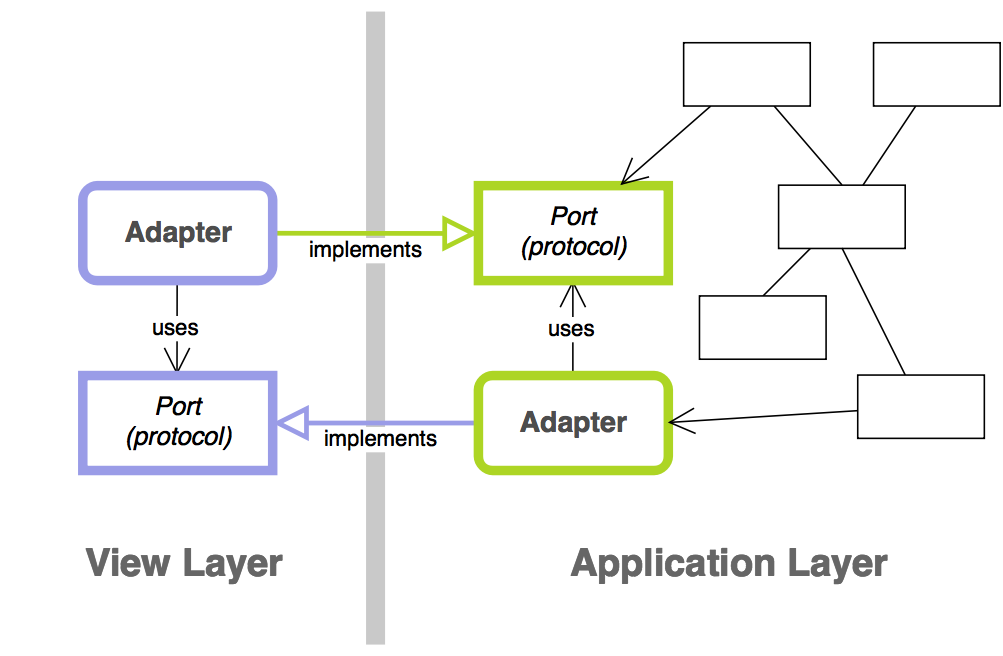

Ports and Adapters

Recall that the basic idea of this architectural style is this: separate queries from commands and isolate layers through ports and adapters. Ports are interfaces (protocols) declared in one layer, while Adapters are classes from other layers which satisfy a Port’s specification:

Instead of one adapter knowing about its collaborator on the other side of the boundary, each adapter only knows a protocol from its module. That marks a dependency. The actual implementation of that protocol is injected. This move is sometimes called “Dependency Inversion,” because you don’t go the naive route and depend on a component from another module but instead depend on a protocol from your own module that others satisfy. The “inversion,” then, is the inversion of arrow directions.

This is nothing new to the code, actually. For example, BoxRepository is a port of the domain to which CoreDataBoxRepository from infrastructure is an adapter. Similarly, the HandlesItemListEvents protocol from the user interface layer is implemented by an application service.

I want to refactor HandlesItemListEvents to pay more attention to command–query separation.

Concerns With the Naive Approach

Have a look at the event handling protocol again:

provisionNewBoxId() -> BoxId

In fact, this method is kind of a mix between typical data source and delegate method. It’s intent is a command, suitable for user interaction events. But it’s also meant to return an object like a factory or data source does.

It should be rephrased as such:

provisionBox()

newBoxId() -> BoxId

The two processes can’t be split up in the Application Service, though. With the current expectations in place, newBoxId() would have to return the last ID the service had provisioned. This way, everything will fall apart too easily once provisionBoxId() is called twice. Just think about concurrency. The contract to call both methods in succession only can’t be enforced, so better not rely on it.

Another alternative is to model it as such:

newBoxId() -> BoxId

provisionBox(_: BoxId)

The service will be an adapter to both domain and infrastructure this way. It’d work, but it’s not what I aim for.

To model the expectation of “provision first, obtain ID second” more explicitly, one could introduce a callback to write the ID to, like so:

provisionBox(andReportBoxId: (BoxId) -> Void)

I don’t like how that reads, though. And since there’s just a single window present, we can formalize this as another protocol from the point of view of BoxAndItemService.

My very first take:

1 protocol ConsumesBoxId: class {

2 func consume(boxId: BoxId)

3 }

4

5 class BoxAndItemService: HandlesItemListEvents {

6 // Output port:

7 var boxIdConsumer: ConsumesBoxId?

8

9 func provisionBox() {

10 let repository = ServiceLocator.boxRepository()

11 let boxId = repository.nextId()

12 storeNewBox(withId: boxId, into: repository)

13 reportToConsumer(boxId: boxId)

14 }

15

16 fileprivate func storeNewBox(withId boxId: BoxId,

17 into repository: BoxRepository) {

18

19 let box = Box(boxId: boxId, title: "New Box")

20 repository.addBox(box)

21 }

22

23 fileprivate func reportToConsumer(boxId: BoxId) {

24 // Thanks to optional chaining, a non-existing boxIdConsumer

25 // will simply do nothing here.

26 boxIdConsumer?.consume(boxId: boxId)

27 }

28 }

Instead of querying BoxAndItemService for an ID, the view controller can now command it to provision a new Box. The service won’t do anything else. Clicking the button will add a Box as it says on the label, but it won’t change the view. The design of these components is flexible and the service doesn’t know the consumer. It is not tied to a view component. You could say that it’s just a coincidence the ItemViewController in return receives the command to consume() a BoxId. This, in turn, will trigger adding a new node with the appropriate BoxId to the outline view.

Using Domain Services and Domain Events

What reportToConsumer(boxId:) does equals the intent of the well-known observer pattern. In Cocoa, we usually send notifications. This is more like calling a delegate because it’s a 1:1 relationship instead of the many-to-one observer pattern relationship:

func reportToConsumer(box: Box) {

boxConsumer?.consume(box)

}

But I notice the Application Service BoxAndItemService is now doing these things:

- it sets up the aggregate

Box - it adds the aggregate instance to its repository

- it notifies interested parties (limited to 1) of additions

Essentially, that’s the job of a Domain Service.

The domain has a few data containers, but no means to create Aggregates or manipulate data. The application layer, being client to the domain, shouldn’t replace domain logic. Posting “Box was created” events is the domain’s responsibility.

Using NotificationCenter as a domain event publisher, BoxAndItemService loses part of its concerns in favor of a Domain Service, ProvisioningService:

1 open class ProvisioningService {

2 let repository: BoxRepository

3

4 var eventPublisher: NotificationCenter {

5 return DomainEventPublisher.defaultCenter()

6 }

7

8 public init(repository: BoxRepository) {

9 self.repository = repository

10 }

11

12 open func provisionBox() {

13 let boxId = repository.nextId()

14 let box = Box(boxId: boxId, title: "New Box")

15

16 repository.addBox(box)

17

18 eventPublisher.post(

19 name: Events.boxProvisioned,

20 object: self,

21 userInfo: ["boxId" : boxId.identifier])

22 }

23

24 open func provisionItem(inBox box: Box) {

25 let itemId = repository.nextItemId()

26 let item = Item(itemId: itemId, title: "New Item")

27

28 box.addItem(item)

29

30 let userInfo = [

31 "boxId" : box.boxId,

32 "itemId" : itemId

33 ]

34 eventPublisher.post(

35 name: Events.boxItemProvisioned,

36 object: self,

37 userInfo: userInfo)

38 }

39

40 // (Mis)using enum as a namespace for notifications:

41 enum Events {

42 static let boxProvisioned =

43 Notification.Name(rawValue: "Box Provisioned")

44 static let boxItemProvisioned =

45 Notification.Name(rawValue: "Box Item Provisioned")

46 }

47 }

I’m not all that keen about the way NotificationCenters work. Dealing with the userInfo parameter is error-prone; both during consumption and creation you can have a typo in a key and end up with a runtime error or unexpected behavior.

I think provisionItem doesn’t read too well, but it’s not the worst method in human history, either. But getting the data out is getting bad:

let boxInfo = notification.userInfo?["boxId"] as! NSNumber

let boxId = BoxId(fromNumber: boxInfo)

It’s hard to read and complicated when compared to, say:

let boxId = boxCreatedEvent.boxId

To introduce another layer of abstraction is a good idea, especially since Swift’s structs make it really easy to create Domain Events. It will improve the code, although you’ll have to weigh the additional cost of developing and testing this very layer of abstraction. For the sake of this sample application, I prefer not to over-complicate things even more and stick to plain old notifications for now.

To replace the command–query-mixing methods from before, there needs to be an event handler which subscribes to Domain Events in the application layer and displays the additions in the view.

Before I expand the Domain with these event types, though, we’ll have a look at another refactoring in the Application layer.

Part 3: Putting a Domain in Place

For the most part of this exercise, the Domain consisted of two Entities: Box and Item. It wasn’t a domain model worth talking about. There were data containers without any behavior at all. There were no business rules except managing Items in Boxes.

This changed a bit when I realized I had mixed Domain Service and Application Service into a single object. The resulting ProvisioningService in the domain creates Entities, adds them to the repository, and notifies interested parties of the event.

Notifications are useful for auto-updating the view as I mentioned in the last part already. They are useful for populating an event store, too: persist the events themselves instead of Entity snapshots to replay changes and thus synchronize events across multiple clients, for example. This is called Event Sourcing and replaces traditional database models to persist Entity states. Digging into this goes way beyond the scope of this book, but I’m eager to try it in the future (hint, hint).

Introducing Events in Place of Notifications

In the last part, I ended up using NotificationCenter to send events. Notifications are easy to use and Foundation provides objects that are well-known. I don’t like how working with a notification’s userInfo dictionary gets in the way in Swift, though. Objective-C was very lenient when you used dictionaries. That introduced a new source of bugs, but if you enjoy dynamic typing, it worked very well. Swift seems to favor new paradigms that enforce strong typing.

Swift Is Sticking Your Head Right at the Problem

In Objective-C, I’d send and access the “Box was created” event info like this:

// Sending

NSDictionary *userInfo = @[@"boxId": @(boxId.identifier)];

[notificationCenter postNotificationName:kBoxProvisioned,

object:self,

userInfo:userInfo];

// Receiving

int64_t identifier = notification.userInfo["boxId"].longLongValue;

[BoxId boxIdWithIdentifier:identifier];

Swift 3 allows sending notifications with with number value types directly. We don’t have to wrap them in NSNumber anymore. Still, the force-unwrapping and the forced cast make me nervous in Swift because they point out a brittle piece of code:

// Sending

let userInfo = ["boxId" : boxId.identifier]

notificationCenter.post(name: kBoxProvisioned,

object: self, userInfo: userInfo)

// Receiving

let boxInfo = notification.userInfo!["boxId"] as! NSNumber

let identifier = boxInfo.int64Value

let boxId = BoxId(identifier: identifier)

I settled for sending IDs only because putting ID and title makes things complicated for the “Item was created” event. There, I’d have to use nested dictionaries. A JSON representation would look like this:

{

box: {

id: ...

}

item: {

id: ...

title: "the title"

}

}

Accessing nested dictionaries in Swift is even worse, though, so I settled with supplying two IDs only. On the downside, every client now has to fetch data from the repository to do anything with the event. That’s nuts.

The relative pain I experience with Swift here highlights the problems Objective-C simply assumed we’d take care of: there could be no userInfo at all, there could be no value for a given key, and there could be a different kind of value than you expect.

It’s always a bad idea to simply assume that the event publisher provided valid data in dictionaries. Force-unwrapping and force-casting will accidentally break sooner or later. What if you change dictionary keys in the sending code but forgot to update all client sites? Defining constants remedies the problem a bit. But the structure of a dictionary is always opaque, and if you change it, you have to change multiple places in your code. It’s a good code heuristic to look for changes that propagate through your code base. If you have to touch more than 1 place to perform a change, that’s an indicator of worse than optimal encapsulation: these co-variant parts in your app depend on one another but don’t show their dependency explicitly.

So you have to perform sanity checks to catch invalid events anyway, in Objective-C just as much as in Swift.

Using real event objects will work wonders. Serializing them into dictionaries and de-serializing userInfo into events will encapsulate the sanity checks and provide usable interfaces tailored to each event’s use. There’s only one place you need to worry about if you want to change the nature of an event.

Event Value Types

An event should be a value type, and thus a struct. It assembles a userInfo dictionary. For NotificationCenter convenience, it also assembles a Notification object:

1 // Provide a typealias for brevity and readability

2 public typealias UserInfo = [AnyHashable : Any]

3

4 public struct BoxProvisionedEvent: DomainEvent {

5

6 public static let eventName = Notification.Name(

7 rawValue: "Box Provisioned Event")

8

9 public let boxId: BoxId

10 public let title: String

11

12 public init(boxId: BoxId, title: String) {

13 self.boxId = boxId

14 self.title = title

15 }

16

17 public init(userInfo: UserInfo) {

18 let boxIdentfier = userInfo["id"] as! IntegerId

19 let title = userInfo["title"] as! String

20 self.init(boxId: BoxId(boxIdentfier), title: title)

21 }

22

23 public func userInfo() -> UserInfo {

24 return [

25 "id" : boxId.identifier,

26 "title" : title

27 ]

28 }

29 }

The underlying protocol is really simple:

1 public protocol DomainEvent {

2 static var eventName: Notification.Name { get }

3

4 init(userInfo: UserInfo)

5 func userInfo() -> UserInfo

6 }

When publishing an event, these properties can be used to convert to a Notification. I used to use a free notification(_:) function for that:

func notification<T: DomainEvent>(event: T) -> Notification {

return Notification(name: T.eventName, object: nil,

userInfo: event.userInfo())

}

Now with protocol extensions, the conversion can be coupled more closely to the DomainEvent protocol, getting rid of the free function:

extension DomainEvent {

public func notification() -> Notification {

return Notification(

name: type(of: self).eventName,

object: nil,

userInfo: self.userInfo())

}

func post(notificationCenter: NotificationCenter) {

notificationCenter.post(self.notification())

}

}

See the convenience method post(notificationCenter:)? That can come in handy when testing the actual sending of an event if you override it in the tests.

Now BoxProvisionedEvent wraps the Notification in something more meaningful to the rest of the app. It also provides convenient accessors to its data, the ID and title of the newly created box. That’s good for slimming-down the subscriber: no need to query the repository for additional data.

There’s a DomainEventPublisher which takes care of the actual event dispatch. We’ll have a look at that in a moment. With all these changes in place, the DisplayBoxesAndItems Application Service now does no more than this:

1 class DisplayBoxesAndItems {

2 var publisher: DomainEventPublisher! {

3 return DomainEventPublisher.sharedInstance

4 }

5

6 // ...

7

8 func subscribe() {

9 let mainQueue = OperationQueue.mainQueue()

10

11 boxProvisioningObserver = publisher.subscribe(

12 BoxProvisionedEvent.self, queue: mainQueue) {

13 [weak self] (event: BoxProvisionedEvent!) in

14

15 let boxData = BoxData(boxId: event.boxId, title: event.title)

16 self?.consumeBox(boxData)

17 }

18

19 // ...

20 }

21

22 func consumeBox(boxData: BoxData) {

23 consumer?.consume(boxData)

24 }

25

26 // ...

27 }

The subscribe method is interesting. Thanks to Swift generics, I can specify an event type using TheClassName.self (the equivalent to [TheClassName class] in Objective-C) and pipe it through to the specified block to easily access the values.

The conversion of Notification to the appropriate domain event takes place in the DomainEventPublisher:

1 func subscribe<T: DomainEvent>(

2 _ eventKind: T.Type,

3 queue: OperationQueue,

4 usingBlock block: (T) -> Void)

5 -> DomainEventSubscription {

6

7 let eventName: String = T.eventName

8 let observer = notificationCenter.addObserver(forName: eventName,

9 object: nil, queue: queue) {

10 notification in

11

12 let userInfo = notification.userInfo!

13 let event: T = T(userInfo: userInfo)

14 block(event)

15 }

16

17 return DomainEventSubscription(observer: observer, eventPublisher: self)

18 }

It takes some getting used to Swift to read this well. I’ll walk you through it.

Let’s stick to the client code from above and see what subscribing to BoxProvisionedEvents does:

- The type of the

eventKindargument should the type (not instance!) of a descendant ofDomainEvent. That’s whatBoxProvisionedEvent.selfis. You don’t pass in an actual event, but it’s class (or “type”). Interestingly, this value is of no use but to setT, the generics type placeholder. - The

block(line 3) yields an event object of typeT(which becomes an instance ofBoxProvisionedEvent, for example) - The

eventName(line 4) will be, in this example case,Box Provisioned Event.DomainEvents have a property calledeventNameto return a string which becomes the notification name. - The actual observer is a wrapper around the

blockspecified by the client. The wrapper creates an event of typeT. AllDomainEvents must provide the deserializing initializerinit(userInfo: [Hashable : Any]), and so doesT.

When a BoxProvisioned event is published, it is transformed into a Notification. The notification is posted as usual. The wrapper around the client’s subscribing block receives the notification, de-serializes a BoxProvisioned event again, and provides this to the client.

DomainEventSubscription is a wrapper around the observer instances NotificationCenter produces. This wrapper unsubscribes upon deinit automatically, so all you have to do is store it in an attribute which gets nilled-out at some point.

It took some trial and error to get there, but it works pretty well.3