Part 2: Sending Messages Inside of the App

I tried to prepare all of the app’s components so far in isolation and not worry much about the integration. In other words, running the app will show that things don’t seem to work. The basic structure is in place, but there’s virtually no action. That’s changing in this part.

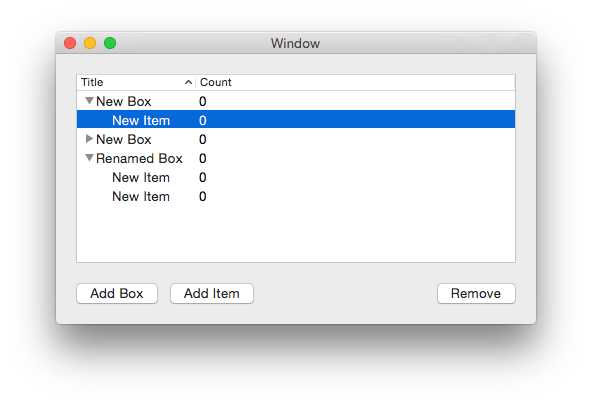

The app window is going to look like this:

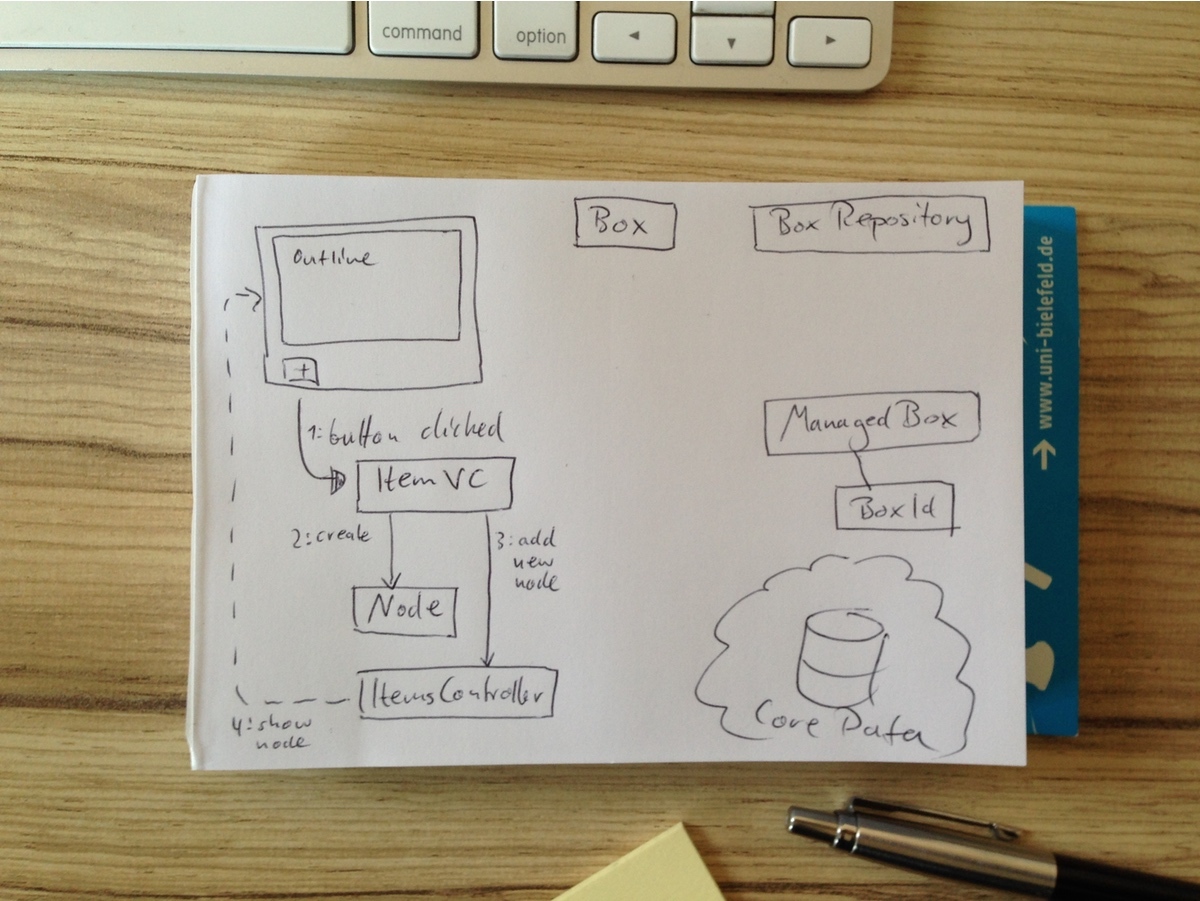

At the moment, the state of the app is the following:

- The user interface is operational but doesn’t persist data. The

ItemViewControllerreacts to button presses and creates node objects. - The Core Data part of infrastructure seems to work fine according to the tests but doesn’t receive any commands, yet.

- The domain is particularly boring. It has no behavior at all. Until now, the whole demo application is centered around getting user input to the data store. This will not change until the next part. It’s nonsensical to work this way of course when the domain should be the very key component of the application.

- There’s no event handling at all, as in “User adds a Box to the list”. There’s no layer between user interface and domain.

This part will focus on the integration and various methods of passing messages between components of the app. When I figured out the structure of the app in the last sections, now I worry more about designing the processing of information and performang actions. There are a few attractive options to consider:

- Cocoa’s classic delegate pattern to obtain objects (“data source”) and handle interactions (“delegate”)

- Ports & Adapters-style command-only interfaces, adhering to CQRS2

- Leveraging Domain Events (since there’s no domain worth speaking of, we’ll defer exploring that option to part 3)

We’ll look at all of these in detail.

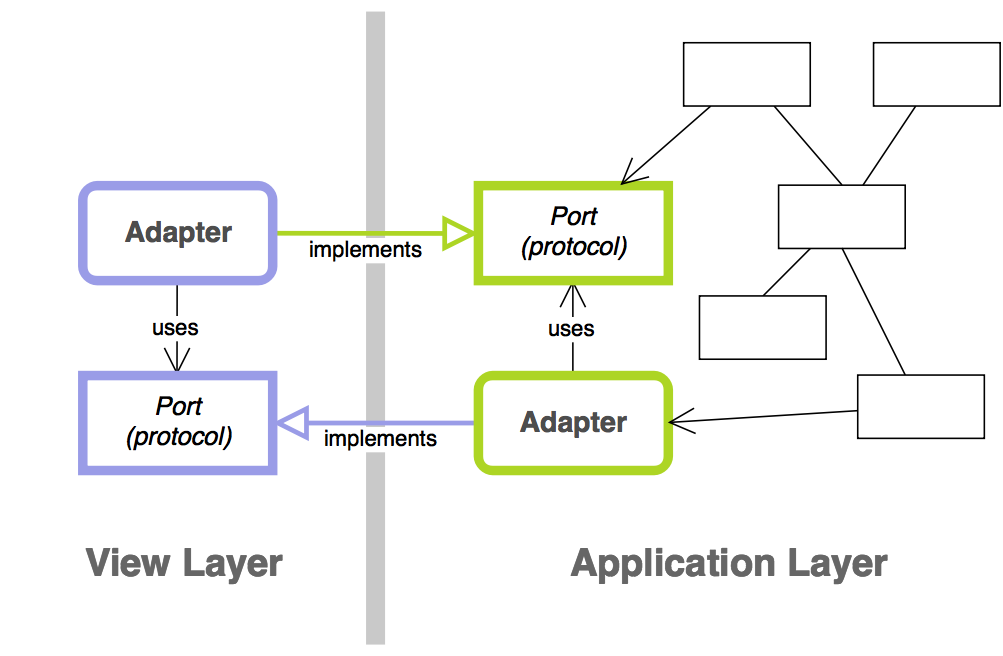

Ports and Adapters

Recall that the basic idea of this architectural style is this: separate queries from commands and isolate layers through ports and adapters. Ports are interfaces (protocols) declared in one layer, while Adapters are classes from other layers which satisfy a Port’s specification:

Instead of one adapter knowing about its collaborator on the other side of the boundary, each adapter only knows a protocol from its module. That marks a dependency. The actual implementation of that protocol is injected. This move is sometimes called “Dependency Inversion,” because you don’t go the naive route and depend on a component from another module but instead depend on a protocol from your own module that others satisfy. The “inversion,” then, is the inversion of arrow directions.

This is nothing new to the code, actually. For example, BoxRepository is a port of the domain to which CoreDataBoxRepository from infrastructure is an adapter. Similarly, the HandlesItemListEvents protocol from the user interface layer is implemented by an application service.

I want to refactor HandlesItemListEvents to pay more attention to command–query separation.

Concerns With the Naive Approach

Have a look at the event handling protocol again:

provisionNewBoxId() -> BoxId

In fact, this method is kind of a mix between typical data source and delegate method. It’s intent is a command, suitable for user interaction events. But it’s also meant to return an object like a factory or data source does.

It should be rephrased as such:

provisionBox()

newBoxId() -> BoxId

The two processes can’t be split up in the Application Service, though. With the current expectations in place, newBoxId() would have to return the last ID the service had provisioned. This way, everything will fall apart too easily once provisionBoxId() is called twice. Just think about concurrency. The contract to call both methods in succession only can’t be enforced, so better not rely on it.

Another alternative is to model it as such:

newBoxId() -> BoxId

provisionBox(_: BoxId)

The service will be an adapter to both domain and infrastructure this way. It’d work, but it’s not what I aim for.

To model the expectation of “provision first, obtain ID second” more explicitly, one could introduce a callback to write the ID to, like so:

provisionBox(andReportBoxId: (BoxId) -> Void)

I don’t like how that reads, though. And since there’s just a single window present, we can formalize this as another protocol from the point of view of BoxAndItemService.

My very first take:

1 protocol ConsumesBoxId: class {

2 func consume(boxId: BoxId)

3 }

4

5 class BoxAndItemService: HandlesItemListEvents {

6 // Output port:

7 var boxIdConsumer: ConsumesBoxId?

8

9 func provisionBox() {

10 let repository = ServiceLocator.boxRepository()

11 let boxId = repository.nextId()

12 storeNewBox(withId: boxId, into: repository)

13 reportToConsumer(boxId: boxId)

14 }

15

16 fileprivate func storeNewBox(withId boxId: BoxId,

17 into repository: BoxRepository) {

18

19 let box = Box(boxId: boxId, title: "New Box")

20 repository.addBox(box)

21 }

22

23 fileprivate func reportToConsumer(boxId: BoxId) {

24 // Thanks to optional chaining, a non-existing boxIdConsumer

25 // will simply do nothing here.

26 boxIdConsumer?.consume(boxId: boxId)

27 }

28 }

Instead of querying BoxAndItemService for an ID, the view controller can now command it to provision a new Box. The service won’t do anything else. Clicking the button will add a Box as it says on the label, but it won’t change the view. The design of these components is flexible and the service doesn’t know the consumer. It is not tied to a view component. You could say that it’s just a coincidence the ItemViewController in return receives the command to consume() a BoxId. This, in turn, will trigger adding a new node with the appropriate BoxId to the outline view.

Using Domain Services and Domain Events

What reportToConsumer(boxId:) does equals the intent of the well-known observer pattern. In Cocoa, we usually send notifications. This is more like calling a delegate because it’s a 1:1 relationship instead of the many-to-one observer pattern relationship:

func reportToConsumer(box: Box) {

boxConsumer?.consume(box)

}

But I notice the Application Service BoxAndItemService is now doing these things:

- it sets up the aggregate

Box - it adds the aggregate instance to its repository

- it notifies interested parties (limited to 1) of additions

Essentially, that’s the job of a Domain Service.

The domain has a few data containers, but no means to create Aggregates or manipulate data. The application layer, being client to the domain, shouldn’t replace domain logic. Posting “Box was created” events is the domain’s responsibility.

Using NotificationCenter as a domain event publisher, BoxAndItemService loses part of its concerns in favor of a Domain Service, ProvisioningService:

1 open class ProvisioningService {

2 let repository: BoxRepository

3

4 var eventPublisher: NotificationCenter {

5 return DomainEventPublisher.defaultCenter()

6 }

7

8 public init(repository: BoxRepository) {

9 self.repository = repository

10 }

11

12 open func provisionBox() {

13 let boxId = repository.nextId()

14 let box = Box(boxId: boxId, title: "New Box")

15

16 repository.addBox(box)

17

18 eventPublisher.post(

19 name: Events.boxProvisioned,

20 object: self,

21 userInfo: ["boxId" : boxId.identifier])

22 }

23

24 open func provisionItem(inBox box: Box) {

25 let itemId = repository.nextItemId()

26 let item = Item(itemId: itemId, title: "New Item")

27

28 box.addItem(item)

29

30 let userInfo = [

31 "boxId" : box.boxId,

32 "itemId" : itemId

33 ]

34 eventPublisher.post(

35 name: Events.boxItemProvisioned,

36 object: self,

37 userInfo: userInfo)

38 }

39

40 // (Mis)using enum as a namespace for notifications:

41 enum Events {

42 static let boxProvisioned =

43 Notification.Name(rawValue: "Box Provisioned")

44 static let boxItemProvisioned =

45 Notification.Name(rawValue: "Box Item Provisioned")

46 }

47 }

I’m not all that keen about the way NotificationCenters work. Dealing with the userInfo parameter is error-prone; both during consumption and creation you can have a typo in a key and end up with a runtime error or unexpected behavior.

I think provisionItem doesn’t read too well, but it’s not the worst method in human history, either. But getting the data out is getting bad:

let boxInfo = notification.userInfo?["boxId"] as! NSNumber

let boxId = BoxId(fromNumber: boxInfo)

It’s hard to read and complicated when compared to, say:

let boxId = boxCreatedEvent.boxId

To introduce another layer of abstraction is a good idea, especially since Swift’s structs make it really easy to create Domain Events. It will improve the code, although you’ll have to weigh the additional cost of developing and testing this very layer of abstraction. For the sake of this sample application, I prefer not to over-complicate things even more and stick to plain old notifications for now.

To replace the command–query-mixing methods from before, there needs to be an event handler which subscribes to Domain Events in the application layer and displays the additions in the view.

Before I expand the Domain with these event types, though, we’ll have a look at another refactoring in the Application layer.