Prologue

Who Is This Book For?

You have all the best intentions but no clue how to make them a reality: You want to write clean code and you don’t want to end up with ugly and unmaintainable applications.

I was stuck in that same situation. I wanted to write my own apps and found my needs quickly surpassed the guidance of Apple’s documentation and sample codes. Both are a useful resource, but you won’t learn how to scale and create a complex application.

Typical questions include:

- How do you architect a complex application?

- How do you deal with large databases?

- How should you implement background services?

It’s a popular advice that you should not stuff everything into your view controllers to avoid suffering from massive view controller syndrome. But nobody show how that works in apps. Maintainable code is important for an app that grows, so how do you get there?

I focus on laying the foundation for an answer to the first question, how to architect Mac apps. I won’t tell you how to scale your database and how to split your app into multiple services in this book. (But check the website from time to time, because I’ve got something in the making!)

To read this book, you don’t need to be a Cocoa wiz. You don’t even need to be proficient with either Swift or Objective-C: I don’t use crazy stuff like method swizzling or operator overloading or anything that’s hard to grasp, really. When I wrote the first edition of this book in 2014, I just learned Swift myself. So there’s lots of explanation and sense-making along the way. Chances are you already know Swift better required to understand the book.

Here’s what I hope you will learn from this book:

- Your will learn to recognize the core of your application, the Domain, where the business rules belong. This is the very core of your application and it has no knowledge of UIKit, AppKit, whatever-kit – it’s all yours, custom made.

- Consequently, you will learn how to put your view controllers on a diet. We will consider them a mere user interface detail.

- Along the way, you’ll get comfortable with creating your own “POSO”s (Plain Old Swift Objects) that convey information and encapsulate behavior instead of desperately looking for canned solutions.

In short, the message of the book is: don’t look for help writing your app. Learn how to create a solid software architecture you are comfortable with instead, and plug in components from third parties where necessary.

Contributing to the Book Manuscript and Example Project

I believe in empowering people. As a consequence, I also believe in sharing information. That’s why I am open-sourcing the whole book plus example code. You can pay for the packaged product and support my writing, but the content will be freely available for every brave soul trying to make sense of Mac app development.

Your feedback is very welcome, and I appreciate pull requests on GitHub for both the manuscript and the example project: if you spot a typo or a code error, help me fix it! You can also open issues on GitHub to request additional “features:” more details, more explanations, more examples.

So feel free to contribute to this book and the overall project via GitHub:

You can read more about the book project on its dedicated website.

A huge thanks for providing feedback and fixing bugs goes to:

- Jorge D Ortiz Fuentes

- Stanislaw Pankevich

A Note on Reading the Example App Code

Developing an app is an iterative process. Looking at the code of a finished app often leaves you wondering: how did he get to this point?

Experimental code from the first commits won’t be available in the final version, of course, because I’ve surpassed the problems along the way. I leverage the version history of the example app to show the app at every stage of development so you can follow along. The git history becomes a tool to understand the development. Throughout the book, I include links to commits on GitHub so you can checkout the code at a particular stage in the narrative.

When you visit GitHub and download the code as a Zip file, though, you will see the final version. This final version will not reflect intermediate steps of the development process. Refer to the footnotes and the links to git commits if you find you need more context. I explain a lot of the refactorings and discuss most code changes in the book itself so you can follow along easily.

If you cannot understand what a section is about because there’s not enough code to illustrate what’s going on, simply open an issue on GitHub in the book manuscript repository and I’ll revise this in a future edition!

Motivation to Write This Book

I develop apps. My first big Mac application was the Word Counter. Back in 2014, I began to sell it. To actually make money from my own Mac software. And that made me nervous – because what if I introduce tons of bugs and can’t fix them? How do I write high-quality code so I can maintain the app for the next years? These questions drove my initial research that led to the field of software architecture.

For an update in late 2014, I experimented with Core Data to store a new kind of data. That became quite a challenge: using Core Data the way of the documentation and sample codes results in a mess. Core Data gets intermingled everywhere. This little book and the accompanying project document my explorations and a possible solution to decouple Core Data from the rest of the app.

Adding a New Feature to the Word Counter

Rewind to fall 2014: I want to add a new feature to the Word Counter.

Until now, the Word Counter observed key presses and counted words written per app. This is indented to show your overall productivity. But it can’t show progress, another essential metric. The ability to monitor files to track project progress was next on the roadmap.

That feature brings a lot of design changes along:

- Introduce

Projects and associatePaths with them. The domain has to know how to track progress for this new kind of data. - Add background-queue file monitoring capabilities.

- Design new user interface components so the user can manage projects and tracked files’ paths.

- Store daily

PathRecords to keep track of file changes over a long period of time. Without records, no history. Without history, no analysis. - Make the existing productivity history view aware of

Projectprogress.

For the simple productivity metrics, I store application-specific daily records in .plist files. They are easy to set up and get started. But they don’t scale very well. Each save results in a full replacement of the file. After 2 years of usages, for example, my record file clocks in at 3 MB. Someone who tracks even more apps and thus increases record history boilerplate will probably have a much bigger file. The hardware will suffer.

In the long run, I’d transition to SQLite or Core Data. The file monitoring module I am about to develop back in 2014 can use its own isolated persistence mechanism. I decide to use Core Data because it’s so convenient to use.

Isolating the file monitoring module is one thing. To develop the module with proper internal separation of concerns and to design objects is another. Core Data easily entangles your whole application if you pick the path of convenience. That’s usually not a path that scales well once you diverge from the standard way once. In this book, I write about my experience with another path, the path of pushing Core Data to the module or app boundaries and keep the innermost core clean and under control.

Challenges Untangling the Convenient Mess

Back in 2014, I didn’t have any experience displaying nested data using NSOutlineViews. I didn’t have a lot of experience with Core Data. All in all, most of the design decisions and their requirements were new to me.

Teaching myself some AppKit, I fiddled around with providing data to NSOutlineView via NSTreeController. Cocoa Bindings are super useful, but they’re not transparent. When it works, it works; but when it doesn’t, it’s hard to know why. Getting your hands dirty and acquiring hands-on knowledge is important, though, to get a feeling for the framework. Declarative or book knowledge will only get you so far. I managed to get a few use cases and basic interactions right, like appending projects to the list and adding paths to the projects. So an interface prototype without actual function wasn’t too hard to figure out.

Now add Core Data to the equation.

It’s super convenient to use Core Data because the framework takes care of a lot. If you want to manipulate persistent objects directly from your interface, you can ever wire NSObjectController subclasses like the above-mentioned NSTreeController to Core Data entities and skip all of the object creation boilerplate code. An NSTreeController can take care of displaying nested data in an NSOutlineView, adding items relative to the user’s current selection for example.

If you adhere to the limitations of an NSTreeController, that is. It is designed to operate on one type of (Core Data) entity. Unfortunately, users of the Word Counter will edit two kinds of objects, not one: Paths may only be nested below Projects, which in turn are strict root level objects. I have to enforce these rules myself, and I have to add objects to the tree from code on my own.

To tie Core Data entities (or NSManagedObject subclasses) to the user interface is so convenient because it skips all of the layers in between. No view controller, no custom domain objects. This means, in turn, to couple the user interface to the data representation. In other words, the user-facing windows are directly dependent on the database. This may be a clever short cut, but this might also be the reason why your app is getting hard to change and hard to test.

The data representation should stay an implementation detail. I may want to switch from Core Data to a SQLite library later on, just like I’m going to migrate my .plist files to something else in the future. The app has to be partitioned at least into “storing data” and “all the rest” to switch the “storing data” part. To blur all the boundaries is commonly referred to as Big Ball of Mud architecture (or rather “non-architecture”). Partitioning of the app into sub-modules improves clarity. And the convenient use of Core Data interferes with this objective.

In short, using Core Data in the most convenient way violates a lot of the principles I learned and loved to adhere to. Principles that helped me keep the Word Counter code base clean and maintainable. Principles I’m going to show you through the course of this book.

The basic architecture I want to advocate is sometimes called “Clean Architecture”, sometimes “Hexagonal”. There are differences between these two, but I won’t be academic about this. This little book will present you my interpretation on these things first and point you into the right direction to find out more afterwards.

The Example

This book is driven by example. Every pattern used will be put to practice in code.

The example project and this very book you read are the result of me trying to solve a problem in the domain of the Word Counter for Mac. This project is a model, so to speak, to explore solutions.

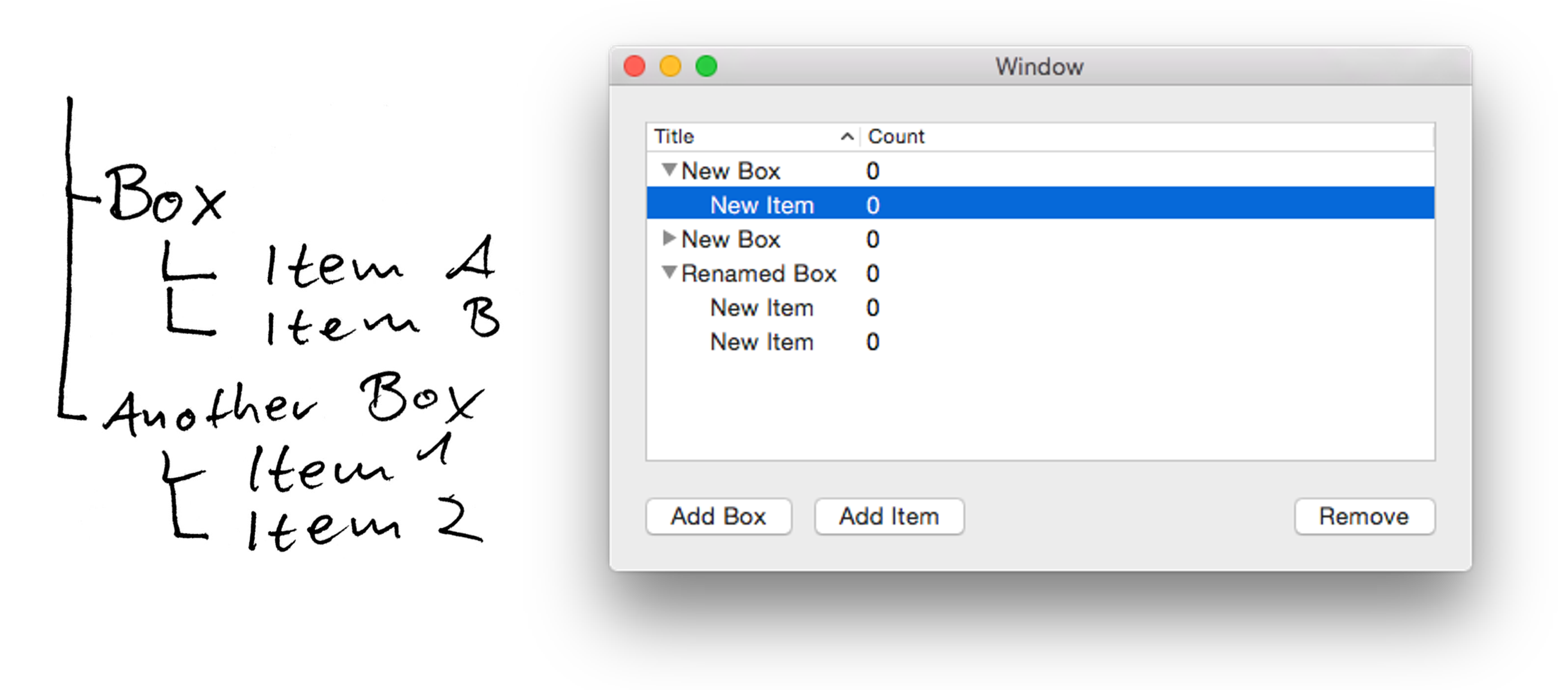

Let’s pretend we want to create an application to organize stuff. It manages items. Items reside inside boxes. Users may create boxes and put items inside them. Boxes may only contain items but no other boxes. Items may contain nothing else. It’s up to the user to decide what an item is, and she may label each box individually, too.

The resulting data can be represented as a very shallow tree structure. That’s why we want to display it as a tree view component, using an NSOutlineView.

Additionally, we decide to use Core Data for persistence.

The corner stones of the application are set. This is a stage of a lot of app visions when they are about to become a reality: not 100% concrete, not thoroughly designed, but you know the basic course of action. Then you get your hands dirty, explore, and learn. I don’t want to advocate a head-over-heels approach here. There’s a lot of useful planning you can do in advance that won’t prevent innovation later. But this book is not the book to teach you that; this book is aimed to take people from a vision and semi-concrete implementation plan to the next level.

Architecture Overview

Out there, you’ll find tons of software architecture approaches and dogmas. I already picked one for this book: a layered clean architecture. It enforces design decisions I found to be very healthy in the long run. With practice, you know where the solution to a problem should be located. And from this context you can derive how to implement something that works. I’ll show you how that works throughout the book. For now, I want to introduce the basic framework so we can think in the same terms.

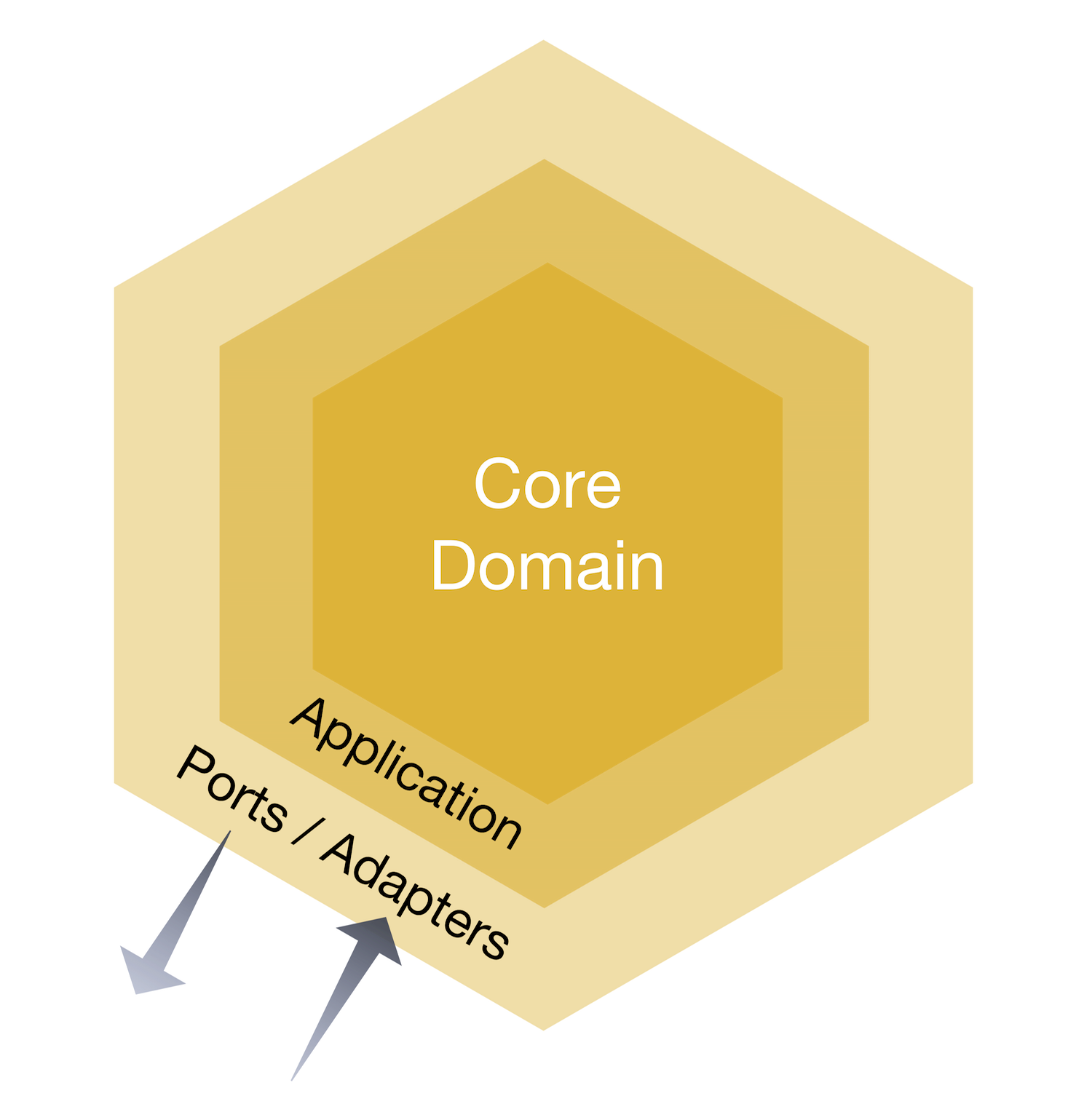

For the sake of this book and the rather simple example application, it suffices to think about the following layers, or nested circles:

- The Domain at the core of your application, dealing with business rules and actual algorithms.

- The so-called Application layer, where interaction with the Domain’s services take place.

- Infrastructure, hosting persistence mechanisms, and User Interface, living in the outermost layer where the app exposes so-called adapters to the rest of the world.

Domain

What’s the core of an app?

Is it the user-facing presentational elements? Is it server communication logic? Or is it your money-maker, maybe a unique feature or data crunching algorithm?

I buy into Domain Driven Design principles and say: the domain is at the core. It’s an abstract thing, really. It’s the realm of language; that’s where we can talk about “items” that are “organized into boxes.” Through setting the stage for the example of this book in the last section, I already created a rough sketch of the domain. This is the problem space. A model of the domain of boxes and items in code is part of the solution space. These are called “domain objects”, and they don’t know a thing about the Cocoa framework or Core Data.

Entities in the Domain

Box and Item are the core parts of this domain. They are Entities: objects that have identity over time. Entities are for example opposed to value objects, which are discardable representations. The integer 42 or the string “living-room” are value objects; their equality depends on their value alone. Two Entities with similar values should nevertheless be unequal. If your dog and my dog are both called “Fido”, they are still different dogs. Similarly, a user of this app should be able to change the title of two or more existing Boxes to “living-room” without changing their identity.

A Box is a specific kind of Entity. It’s an Aggregate of entities (including itself): it has label for its own and takes care of a collection of Items. An Item will only exist inside a Box, so access to it is depending on knowing its Box, first. Being an Aggregate is a strong claim about object dependencies and object access. In a naive approach, you’d query the database for boxes and items independently, combine them for display, and that’s it. The notion of Aggregates changes your job: you only request boxes and the items are included automatically.

To get Box Aggregates, a Repository with a collection-like interface is used. The BoxRepository specifies the interface to get all boxes, remove existing ones, or add new ones. And when it hydrates a Box object from the database, it hydrates the corresponding Items, too. Without a Repository, assembling an Aggregate would be very cumbersome. If you know the classic Gang of Four Design Patterns, you can think of a Repository in terms of a Factory which takes care of complex object creation.

Services of the Domain

In the domain of the Word Counter, for example, there reside a lot of other objects. Some deal with incoming Domain Events like “a word was typed”. There are Recorders which save these events. Bookkeepers hold on to a day’s active records. There’s a lot of other stuff revolving around the process of counting words.

In this example application, there won’t be much going on at the beginning. We will focus on storing and displaying data. That’ll be an example for application wire-framing. There’ll be one particular Domain Service that encapsulates a user intent: to provision new Boxes and Items. This equals creating new Entities. This Domain Service adds the Entities to the Repository so other objects can obtain them later on.

Services in general are objects without identity that encapsulate behavior. You may argue they shouldn’t even have state. They execute commands, but they shouldn’t answer queries. That’s as general a definition I can give without limiting its application too much.

Infrastructure

The domain itself doesn’t implement database access through repositories. It defines the interfaces or protocols, though. The concrete implementation resides elsewhere: in the Infrastructure layer. When the Domain Service reaches “outward” through the Repository interface, it sends data through the Domain’s “ports”. The concrete Core Data Repository implementation is an “adapter” to one of these ports.

A concrete Repository implementation can be a wrapper for an array, becoming an in-memory storage. It can be a wrapper around a .plist file writer, or any other data store mechanism, including Core Data. The Domain doesn’t care about the concrete implementation – that is a mere detail. The Domain only cares about the fulfillment of the contract; that’s why it has 100% control over the protocol definition.

All the Core Data code should be limited to this layer. Exposing the dependency on Core Data elsewhere makes the distinction between Domain and Infrastructure useless. To make the persistence mechanism an implementation detail gives you a lot of flexibility and keeps the rest of the app cleaned from knowledge of this detail. But all the planning and architecture won’t help if you blur the boundaries again and sprinkle Core Data here and there because it’d be more convenient.

Application

Your Domain contains all the business logic. It provides interfaces to clients through Aggregates and Services. A layer around this core functionality is called the Application layer, because it executes functionality of the Domain.

The Client of the Domain

The Domain contains a Service object to provision new Entities. But someone has to call the Domain Service. The application’s user is pressing a button, but how does the button-press translate to using the Domain Services? While we’re at it: where does the view controller come from, where is it created and which objects holds a strong reference to it?

This is where the Application layer comes into play. It contains Application Service objects which hold on to view controllers and Domain Services, for example. The Application layer is the client of the Domain’s functionality.

When the “Add Box” button is pressed, the view controller translates this interaction into a command for the Application layer, which in turn prepares everything to make the Domain provision a new Box instance. Boxes have to be reported to the user interface for display, too. That’s what the Application layer will deal with in use case-centered Service objects.

Glue-Code

You may have asked yourself how the Domain will know which Repository implementation to use in the actual program. The Application layer can take care of this when it initializes and uses the Domain’s services.

“Dependency Injection” is the fancy term for passing a concrete Repository implementation to an object that requires a certain protocol. It’s a trivial concept when you see it in action:

func jsonify(serializer: JSONSerializer) -> JSON {

serializer.add(self.title)

serializer.add(self.items.map { $0.title })

return serializer.json()

}

Instead of creating the JSONSerializer inside the method, the serializer is injected. Whenever the function that uses an objects also creates it, you’ll have a hard time testing its behavior – and that results in a harder time switching collaborating objects later, too.

Apart from this simple application of passing a collaborator around, Dependency Injection as a paradigm can be used to create object clusters, too. Instead of passing in the dependency with a method call, you pass it as a parameter of the initializer. You probably do things like that in your AppDelegete already to wire multiple objects together and pass them to view controllers or navigation controllers. You can use a Dependency Injection library to automate this setup task and configure the dependency network outside your code, but I always found these things to be way too cumbersome. (Then again, I never built huge enterprise software which may benefit from this kind of flexibility.) This book’s example app isn’t complex enough to warrant more than a global storage object for the main dependencies that are going to be used in the Application Services. The Repository implementations are set up on a Service Locator which is usually is a global singleton. I put the Service Locator inside the Infrastructure layer because it mostly consists of Infrastructure parts anyway.

Thus, Infrastructure deals with providing persistence mechanisms to be plugged them into the Domain. Actually calling the methods to set up Domain Services is a matter of the use case objects which I put into the Application layer.