General Information

This chapter explains the basics of how a computer works. It starts with describing operating systems and their history. Then the chapter considers families of modern operating systems and their features. The last section explains a computer program and its execution.

Operating Systems

History of OS Origin

Most computer users understand why an operating system (OS) is needed. Before launching a new application, you usually check its system requirements. These requirements specify the hardware and OS that you need to launch the application.

The system requirements bring us the idea that the OS is a software platform. The application requires this platform for correct working. But where did this requirement come from? Why can’t you just buy a computer and launch the application without any OS?

Our questions seem meaningless at first blush. But let’s consider them from the following point of view. Modern operating systems are multipurpose, and they offer users many features. Each specific user would not use most of these features. However, you cannot disable them. The OS utilizes the computer’s resources intensively for maintaining its features. As a result, the user has much fewer computation resources for his applications. This overhead leads to the computer’s slow work, hanging of the programs, and even rebooting the whole system.

Let’s turn to history to find out the origins of operating systems. The first commercial OS was called GM-NAA I/O. It appeared for the computer IBM 704 in 1956. All earlier computers have worked without any OS. Why didn’t they need it?

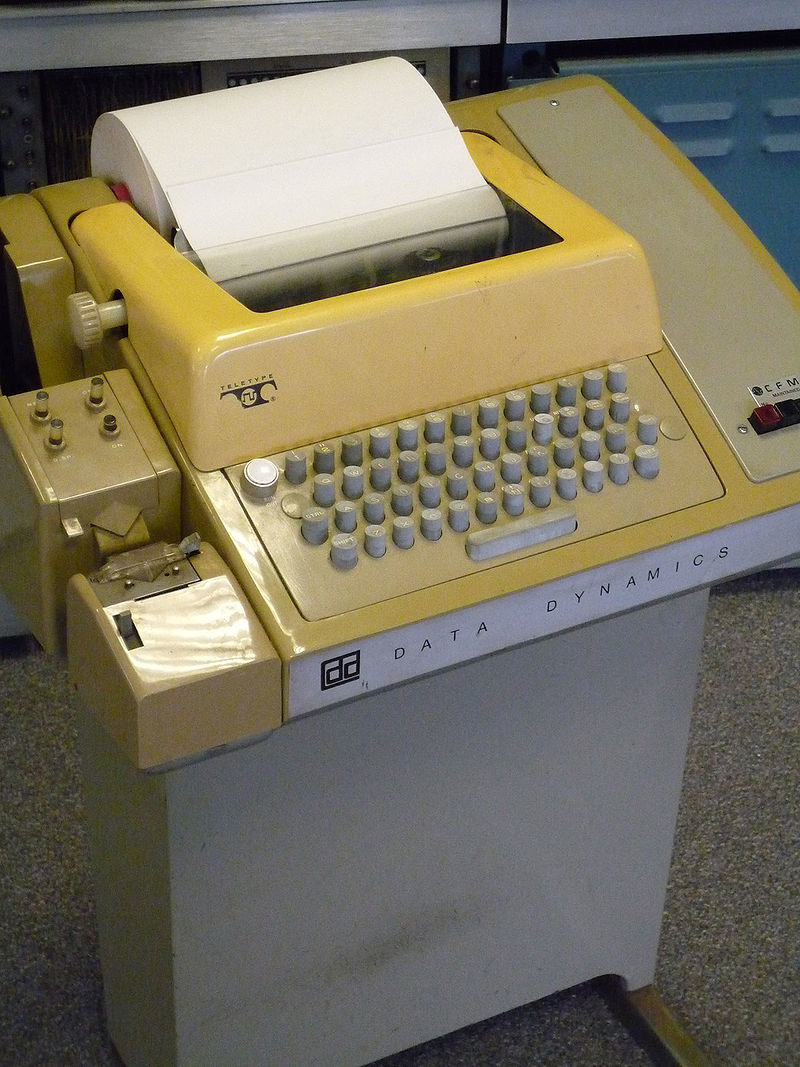

The main reason for having an OS is high computational speed. For example, let’s consider the first electromechanical computer. Herman Hollerith constructed it in 1890. This computer was called a tabulator. It does not require an OS and a program in the modern sense. The tabulator performs a limited set of arithmetic operations only. Its hardware design defines this set of operations.

The tabulator loads input data for computation from punched cards. These cards look like sheets of thick paper with punched holes. A human operator prepares these sheets manually and stacks them in special receivers. The sheets are threaded on the needles in the receivers. Then a short circuit happens in each punched hole. Each short circuit increases the mechanical counter, which is a rotating cylinder. The tabulator displays calculation results on dials that resemble watches.

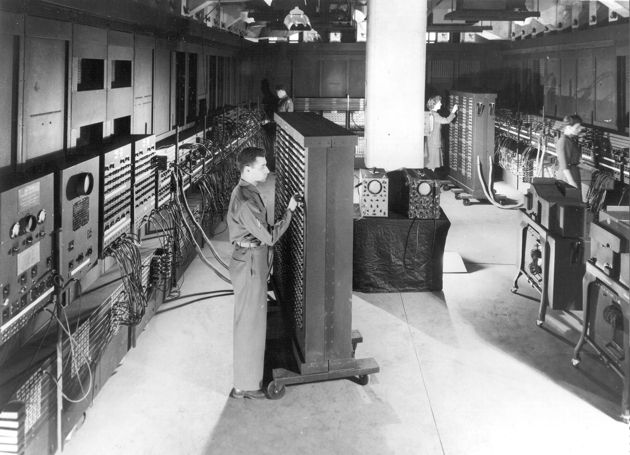

Figure 1-1 shows the tabulator that Hermann Hollerith has constructed.

By modern standards, the tabulator works very slowly. There are several reasons for this. The first one is you need a lot of manual work. At the beginning, you should prepare input data. There was no way to punch the cards automatically. Then you manually load punched cards into the receivers. Both operations require significant efforts and time.

The second reason for low computation speed is mechanical parts. The tabulator contains many of them: needles to read data, rotating cylinders as counters, dials to output the result. All these mechanics work slowly. It takes about one second to perform one elementary operation. No automation can accelerate these processes.

If you look at how the tabulator works, you find no place for OS there. OS just does not have any tasks to do on such a kind of computer.

Tabulators used rotating cylinders for performing calculations. The next generation of computers replaced the cylinders with relays. A relay is a electromechanical element that changes its state due to an electric current.

The German engineer Konrad Zuse designed one of the first relay computers called Z2 in 1939. Then he improved this computer in 1941 and called it Z3. These machines perform a single elementary operation in milliseconds. They are much faster than tabulators. This performance gain happens thanks to applying relays instead of rotating cylinders.

The increased computation speed is the first feature of Zuse’s computers. The second feature is the concept of a computer program. The idea of the universal machine, which follows the algorithm you choose, was fundamentally new at that time.

Z3 computer uses two input devices in parallel for supporting programs. The first one is a receiver for punched cards that resembles the tabulator’s receiver. It reads the program to execute from the card. The second input device is the keyboard. It allows the user to type input data for the program.

The computers with the feature of changing their algorithms became known as programmable or general-purpose.

The invention of programmable computers was a milestone in the development of computer science. Until this moment, machines were able to perform highly specialized tasks only. The construction of these machines was too expensive and unprofitable. This was a reason why commercial investors did not join the projects to design new computers. Only governments invested money there. However, this situation has changed since programmable computers came.

The next step in computer design is the construction of the ENIAC (see Figure 1-2) computer in 1946 by John Eckert and John Mauchly. ENIAC uses a new type of element for performing computations. Vacuum tubes replaced relays there. The tube is a purely electronic device. It does not have any mechanical component as the relay has. Therefore, when the electrical signal comes, the tube’s reaction time is much faster than the relay one. This change increased ENIAC performance by order of magnitude comparing to relay-based machines. The new computer performs single elementary operation in 200 microseconds instead of milliseconds.

Most computer engineers were skeptical about vacuum tubes in the 1940s. The tubes were known for their low reliability and high power consumption. Nobody believed that a tube-based machine could work at all. ENIAC contains around 18,000 vacuum tubes. They burn out often. However, the computer performed the calculations efficiently between the failures. ENIAC was the first successful case of applying vacuum tubes. This case convinced many engineers that such an approach works well.

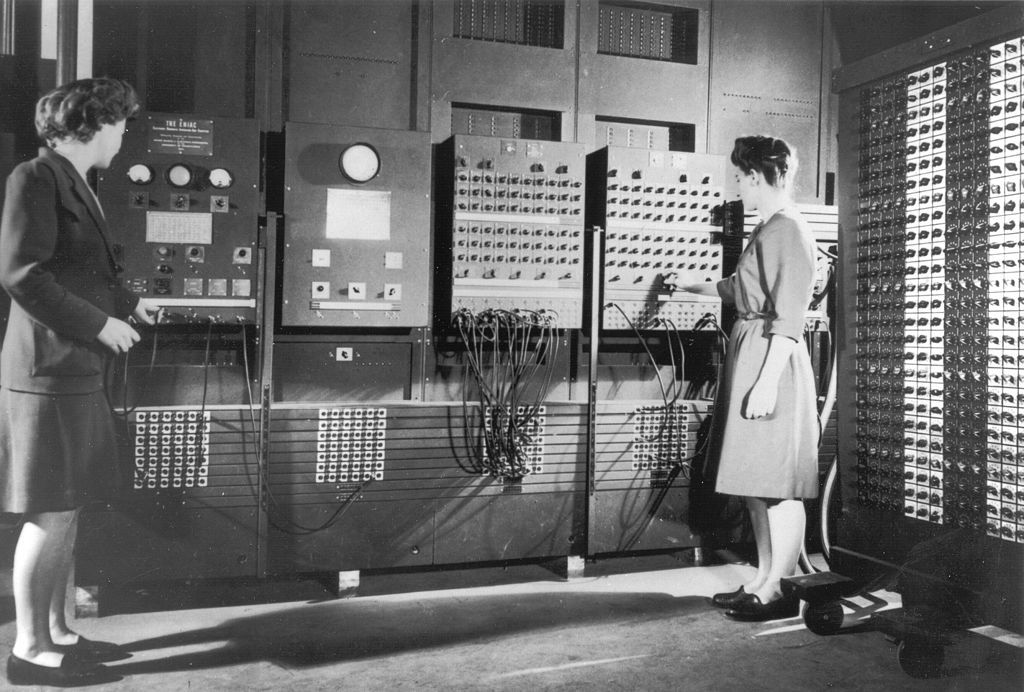

ENIAC is a programmable computer. You can set its algorithm using a combination of switches and jumpers on the control panels. This task requires considerable time and simultaneous work of several people. Figure 1-3 shows one of the panels for programming ENIAC.

ENIAC uses punched cards for reading input data and to output results. This is the same approach as previous models of computers have used. The new feature of ENIAC was storing intermediate results on the cards.

When the ENIAC should calculate a complex task, it can come to a leak of computation resources. However, you can split the task into several subtasks. Then the computer can solve each subtask separately. Storing the intermediate results on the cards helps you to move data from one subtask to another while you reprogram the computer.

Using ENIAC gave a new experience to engineers. It shows that all mechanical operations limit computer performance. These are the mechanical operations in ENIAC: manual reprogramming with switches and jumpers, reading and punching the cards. Each of these operations takes a significant time. Therefore, solving practical tasks with ENIAC is ineffective. The computer itself had an unprecedented performance at that time. However, it was idling most of the time and waiting for reprogramming or receiving input data. These findings initiated the development of new devices for both data input and output.

The next step in computer design is replacing vacuum tubes with transistors. It again increased the computation speed by an order of magnitude. Transistors came together with new input/output devices. It allowed to increase the loading of the computers and reprogram them more often.

When the epoch of transistors started, computers spread beyond government and military projects. Banks and corporations began to exploit machines too. It increases the number and variety of programs running on computers significantly.

Commercial usage of computers brings new requirements. When the computer works in a company, it should execute programs one after another without any delays. Otherwise, the machine does not justify the money spent on it.

New solutions were needed to meet new requirements. The most time-consuming task was switching between programs. Therefore, engineers of General Motors and North American Aviation came to an idea to automate it. They created the first commercial operating system GM-NAA I/O. The primary goal of the system was managing the execution of programs.

The heavy load of computers and the variety of their programs brought another new task. When the computer of that time loads a program, the program defines the hardware’s available features. For example, if the program includes a code to control an output device, you can use it. Otherwise, this device is unavailable.

Suppose that you are a company. You use a particular computer model all the time. The hardware always stays the same. Therefore, you do not change the code that controls your hardware. You just copy this code from one program to another. It takes extra efforts.

Copying hardware-specific code brought engineers to an idea of a special service program. The service program loads together with the user’s application and provides the hardware support. These service programs became part of the first-generation operating systems after a while.

Now it is time to come back to the question, why do you need an OS. We found out that applications could work without them in general. Such applications are still in use today. For example, they are utilities for memory checks and disk partitioning, antiviruses, recovery tools. However, developing such applications takes more time and efforts. They should include the code for supporting all required hardware.

OS usually provides the code for supporting hardware. Why would you not use it? Most modern developers choose this way. It reduces the amount of work and speeds up the release of the applications.

However, a modern OS is a vast complex system. It provides much more features than just hardware support. Let’s consider them too.

OS Features

Why did we start studying programming by considering the OS? OS features are the basis for the application. Let’s consider how it works.

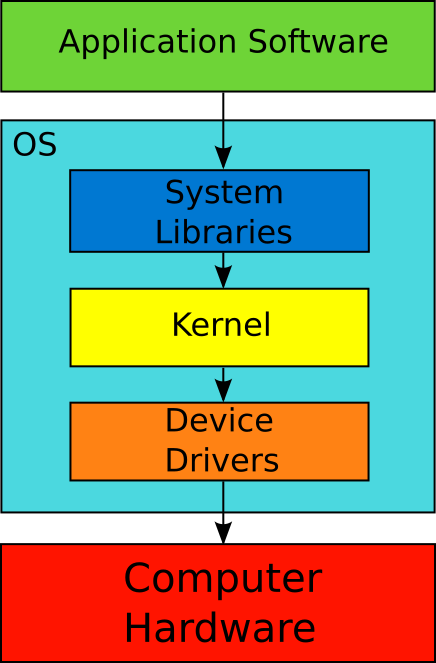

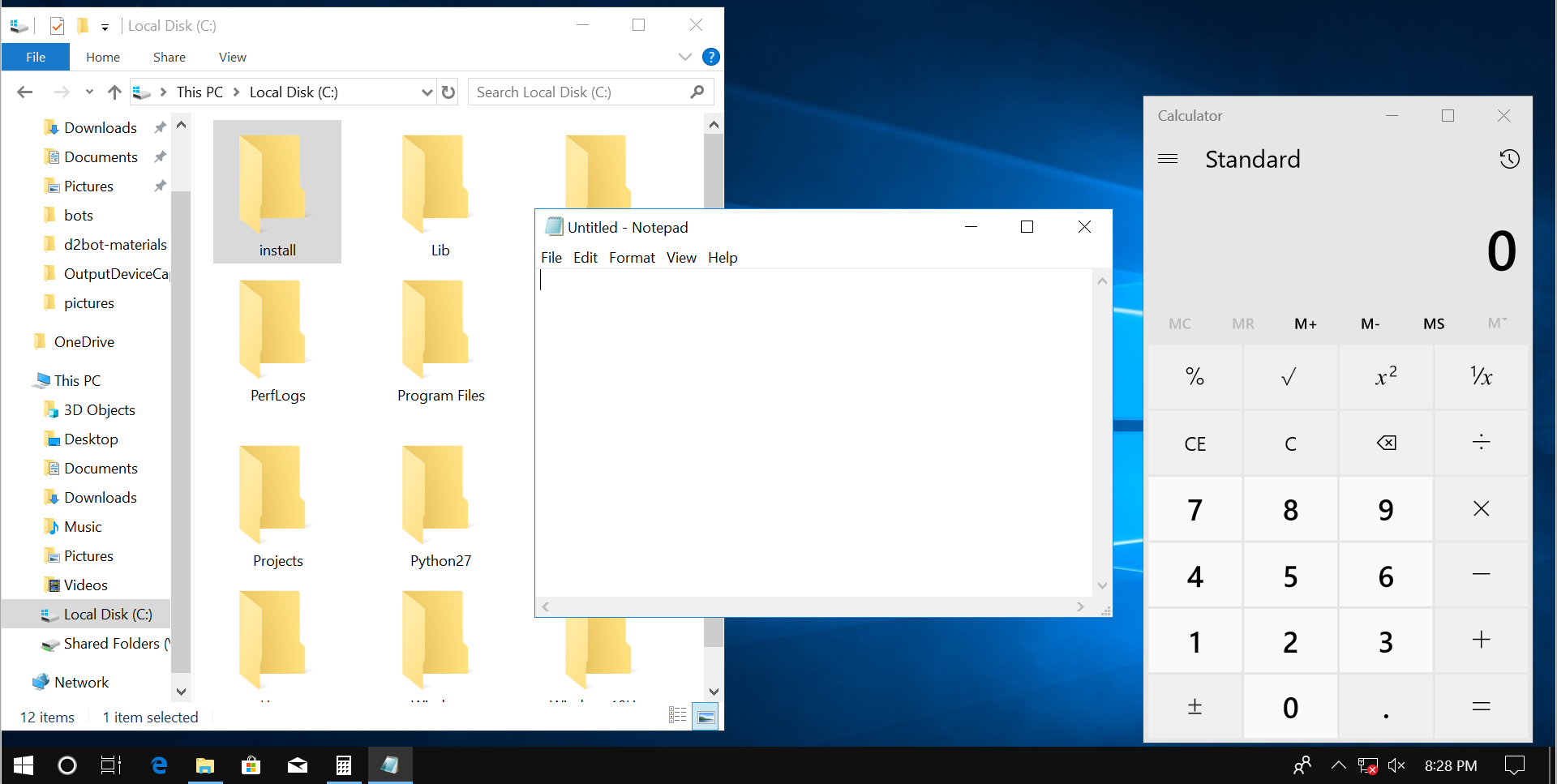

Figure 1-4 demonstrates the interaction between the OS, an application and hardware. Applications are programs that solve practical user tasks. Examples are text editor, calculator, browser. Hardware is all electronic and mechanical components of a computer. For example, these are keyboard, monitor, central processor, video card.

According to Figure 1-4, the application does not interact with hardware directly. The program does it through system libraries. The system libraries are part of the OS. There are rules to access the system libraries. Each application should follow them.

Application Programming Interface or API is the interface that the OS provides to an application to interact with system libraries. In general, the API term means a set of agreements for interacting components of the information system. These agreements become a well-known standard often. For example, the POSIX standard describes the portable API for a family of OSes. The standard guarantees the compatibility of the OS and applications.

OS kernel and device drivers are part of OS. They dictate which hardware features the application can access. When the application interacts with system libraries, the libraries request capabilities of kernel and drivers. If you need the hardware feature and OS does not support it, you cannot use it.

When the application accesses the system library, it calls a library’s function. A function is a program fragment or an independent block of code that performs a certain task. You can imagine the API as a list of all available functions that the application can call. Besides that, API describes the following aspects of the interaction between the OS and applications:

- What action does the OS perform when the application calls the specific system function?

- What data does the function receive as input?

- What data does the function return as a result?

Both the OS and application should follow the API agreements. It guarantees the compatibility of their current versions and future modifications. Such compatibility is impossible without a well-documented and standardized interface.

We have discovered that some applications work without an OS. They are called bare-metal software. This approach works well in some cases. However, the OS provides ready-made solutions for interaction with the computer’s hardware. Without these solutions, developers should take responsibility for managing hardware. It requires significant efforts. Imagine the variety of devices of a modern computer. The application should support all popular models of each device (for example, video cards). Without such support, the application would not work for all users.

Let’s consider the features that the OS provides via the API. We can treat the computer’s hardware as resources. The application uses these resources for performing calculations. The API reflects the list of hardware features that the program can use. Also, the API dictates the order of interaction between several applications and the hardware.

There is an example. Two programs cannot write data to the same area of the hard disk simultaneously. There are two reasons for that:

- A single magnetic head records data on the hard disk. The head can do one task at a time.

- One program can overwrite data of another program in the same memory area. It leads to losing data.

You should place all requests to write data on the disk in a queue because of these two problems. Then each request should be performed separately. The OS takes care of this task.

The kernel (see Figure 1-4) of the OS provides a mechanism for managing access to the hard drive. This mechanism is called file system. Similarly, the OS manages access to all peripheral and internal devices of the computer. Device drivers provide access to the hardware for OS and applications.

We have mentioned peripheral and internal devices. What is the difference between them? Peripherals are all devices that are responsible for inputting, outputting, and storing data permanently. Here are the examples:

- Keyboard

- Mouse

- Microphone

- Monitor

- Speakers

- Hard drive

Internal devices are responsible for processing data, i.e. for executing programs. These are internal devices:

- Central Processing Unit (CPU)

- Random-Access Memory (RAM)

- Video Card (graphics processing unit or GPU).

The OS provides access to the computer’s hardware. At the same time, the OS has something besides the hardware management to share with user’s applications. The system libraries have grown from the program modules to serve the devices. However, some libraries of modern OSes provide complex algorithms for processing data. Let’s consider an example.

There is the Windows OS component called Graphics Device Interface (GDI). It provides algorithms for manipulating graphic objects. GDI allows you to create a user interface for your application with minimal efforts. Then you can use the monitor to display this interface.

The system libraries with useful algorithms (like GDI) are software resources of the OS. These resources are already installed on your computer. You just need to know how to use them. Besides that, the OS also provides access to third-party libraries and their algorithms. You can install these libraries separately and use them in your applications.

The OS manages hardware and software resources. Also, it organizes the joint work of running programs. The OS performs several non-trivial tasks to launch an application. Then the OS tracks its work. If the application violates some agreements (like memory usage), the OS terminates it. We will consider launching and executing the program in detail in the next section.

If the OS is multi-user, it controls access to the data. It is an important security feature. This feature allows the user to access the following file system objects:

- Files and directories that the user owns.

- Files and directories that somebody has shared with the user.

It allows several persons to use the same computer safely.

Here is the summary. The modern OS has all following features:

- It provides and manages access to hardware resources of the computer.

- It provides its own software resources.

- It launches applications.

- It organizes the interaction of applications with each other.

- It controls access to users’ data.

You can guess that it is impossible to launch several applications in parallel without the OS. You are right. When you develop an application, you have no idea how a user will launch it. The user can launch your application together with another one. You cannot foresee this use case. However, the OS responds for launching all applications. It means that the OS has enough information to allocate computer resources properly.

Modern OSes

We have reviewed the OS features in general. Now we will consider modern operating systems. Today you can pick any OS and get very similar features. However, their developers follow different approaches. This leads to implementation difference that can be important for some users.

There is the software architecture term. It means the implementation aspects of the specific software and the solutions that led to them.

All modern OSes have two features that determine the way how users interact with them. These features are multitasking and the graphical user interface. Let’s take a closer look at them.

Multitasking

All modern OSes support multitasking. It means that they can execute multiple programs in parallel. The systems with this feature displaced OSes without it. Why does multitasking so important?

The challenge of efficient usage of computers came in the 1960s. Computers were expensive at that time. Only large companies and universities were able to buy them. These organizations counted every minute of working with their machines. They did not accept any idle time of the hardware because of its huge cost.

Early operating systems executed programs one after another without delays. This approach saves time for switching computer tasks. If you use such an OS, you should prepare several programs and their input data in advance. Then you should write them on the storage device (e.g., magnetic tape). You load the tape to the computer’s reading device. Afterward, the computer executes the programs sequentially and prints their results to an output device (e.g., a printer). This mode of operation is called batch processing.

Batch processing increased the efficiency of using computers in the 1960s. This approach has automated program loading. The human operators became unnecessary for this task. However, the computers still had the bottleneck. The computational power of processors was increasing significantly every year. The speed of peripherals has remained almost the same. It led to CPU idles all the time while waiting for input/output.

Why does CPU idle and wait for peripheral devices? Here is an example. Suppose that the computer from the 1960s runs programs one by one. It reads data from a magnetic tape and prints the results on the printer. The OS loads each program and executes its instructions. Then it loads the next one, and so on.

The problem happens when reading data and printing the results. The time for reading data on the magnetic tape is huge on the CPU scale. This time is enough for the processor to perform many calculations. However, it does not do that. The reason for that is the currently loaded program occupies all computer resources. The same CPU idle happens when printing the results. The printer is a slow electromechanical device.

The CPU idle led OS developers to the concept of multiprogramming. This concept implies that OS loads several programs into the computer memory at the same time. The first program works as long as all resources it needs are available. It stops executing once a required resource is busy. Then OS switches to another program.

Here is an example. Suppose that your application wants to read data from your hard disk. While the disk controller reads the data, it is busy. It cannot process the following requests from the program. Thus, the application waits for the controller. In this case, OS stops executing it and switches to the second program. The computer executes it to the end or until it has all the required resources. When the second program finishes or stops, OS switches tasks again.

Multiprogramming differs from multitasking that modern OSes have. Multiprogramming fits the batch processing mode very well. However, this load balancing concept is not suitable for interactive systems. An interactive system considers each user action as an event (for example, a keystroke). The system should process events immediately when they happen. Otherwise, the user cannot work with the system.

Here is an example of workflow with an interactive system. Suppose that you are typing text in the MS Office document. You press a key and expect to see this symbol on the screen. If the computer requires several seconds to process your keystroke and display the symbol, you cannot work like that. Most of the time, you will wait and check if the computer has processed your keystroke or not. This is inefficient.

Multiprogramming cannot handle events in the interactive system. It happens because you cannot predict when task switching happens next time. OS switches tasks when a program finishes or when it requires a busy resource. Suppose that your text editor is not an active program now. Then you do not know when it can process your keystroke. It can happen in a second or in several minutes. This is unacceptable for a good user interface.

The multitasking concept solves the task of processing events in interactive systems. There were several versions of multitasking before it comes to the current state. Modern OSes use displacing multitasking with pseudo-parallel tasks processing. The idea behind it is to allow the OS to choose an appropriate task for executing at the moment. The OS takes into account the priorities of the running programs. Therefore, a higher priority program receives hardware resources more often than a lower priority one. OS kernel provides this task-switching mechanism. It is called task scheduler.

Pseudo-parallel processing means that the computer executes one task only at any given time. The OS switches tasks so quickly that you can suppose the processing of several programs at once. This concept allows the OS to react immediately to any event. Even though every program and OS component uses hardware resources at strictly defined moments.

There are computers with multiple processors or with multi-core processors. Only these computers can execute several programs at once. The number of the running programs equals the number of cores of all processors approximately. The preemptive multitasking mechanism with constant task switching works on such systems well. It is a universal approach that balances the load regardless of the number of cores. This way, the computer responds to the user’s actions quickly. The number of processor cores does not matter.

User Interface

Modern OSes are able to solve a wide range of tasks. These tasks depend on the computer type where you run the OS. Here are the main types of computers:

- Personal computers (PC) and notebooks.

- Smartphones and tablets.

- Servers.

- Embedded systems.

We will consider OSes for PCs and notebooks only. Apart from multitasking, they provide graphic user interface (GUI). This interface means the way to interact with the system. You launch applications, configure computer devices and OS components via the user interface. Let’s take a look at its history and find how it has reached the current state.

Nobody works with commercial computers interactively before 1960. Digital Equipment Corporation implemented the interactive mode for their minicomputer PDP-1 in 1959. It was a fundamentally new approach. Before that, IBM computers dominated the market in the 1950s. They worked in batch processing mode only. This mode automated program loading and provided high performance for calculation tasks.

The idea of interactive work with the computer appeared first in the SAGE military project. The US Air Force was its customer. The goal of the project was to develop an automated air defense system to detect Soviet bombers.

When working on the SAGE project, engineers faced the problem. The user of the system should analyze data from radars in real-time. If he detects a threat, he should react as quickly as possible and command to intercept the bombers. However, the existed methods of interaction with the computer did not fit this task. They did not allow showing information to the user in real-time and receive his input at any moment.

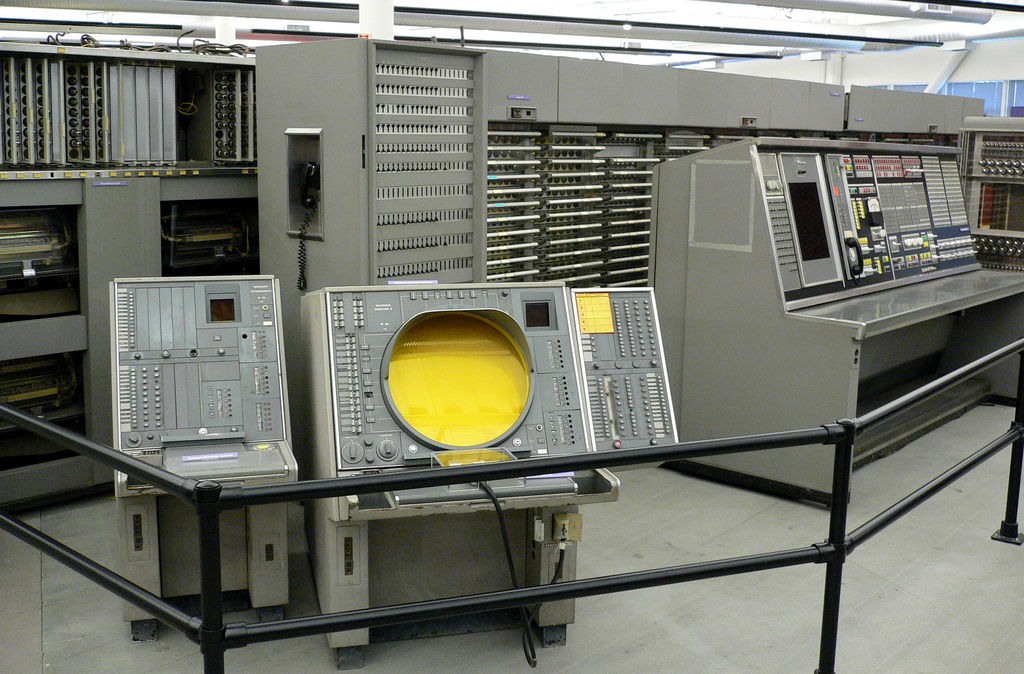

Engineers came to the idea of the interactive mode. They implemented it in the first interactive computer AN/FSQ-7 in 1955 (see Figure 1-5). The computer used the monitor with a cathode-ray tube to display information from radars. The light pen allowed the user to command the system.

The new way of interaction with computers became known in scientific circles. It gained popularity quickly. The existing batch processing mode coped with program execution well. However, this mode was inconvenient for development and debugging applications.

Suppose that you are writing a program for the computer with batch processing. You should prepare your code and write it to the storage device. When the device is ready, you put it in a queue. The computer’s operator takes devices from the queue and loads them to the computer one by one. Therefore, your task can wait in the queue for several hours. Now assume that an error happened in your program. In this case, you should fix it, prepare the new version of the program and write it to the device. You put it in the queue again and wait for hours. Because of this workflow, you need several days to make even a small program working.

The software development workflow differs when you use an interactive mode. You prepare your program and load it to the computer. Then it launches the program and shows you results. Immediately, you can analyze a possible error, fix it and relaunch the program. This workflow accelerates software development and debugging tasks significantly. Now you spend few hours on the task that requires days with batch processing mode.

The interactive mode brought new challenges for computer engineers. This mode requires a system that reacts to user actions immediately. A short reaction time required a new load-balancing mechanism. The multitasking concept became a solution for this issue.

There are alternative solutions for providing interactive mode. For example, there are interactive single-tasking OSes like MS-DOS. MS-DOS was the system for cheap PCs of the 1980s.

However, it was inadvisable to apply single-tasking in the 1960s when computers were too expensive. These computers executed many programs in parallel. Such a mode was called time-sharing. It allows sharing expensive hardware resources among several users. The single-tasking approach does not fit such a use case because it is not compatible with time-sharing.

When the first relatively cheap personal computers appeared in the 1980s, they used single-tasking OSes. Such systems require fewer hardware resources than their analogs with multitasking. Despite its simplicity, single-tasking OSes support interactive mode for the running program. This mode became especially attractive for PC users.

When interactive mode became more and more popular, computer engineers meet a new challenge. The existing devices for interacting with computers turned out to be inconvenient. Magnetic tapes and printers were widespread through the 1950s and early 1960s. They did not fit interactive mode absolutely.

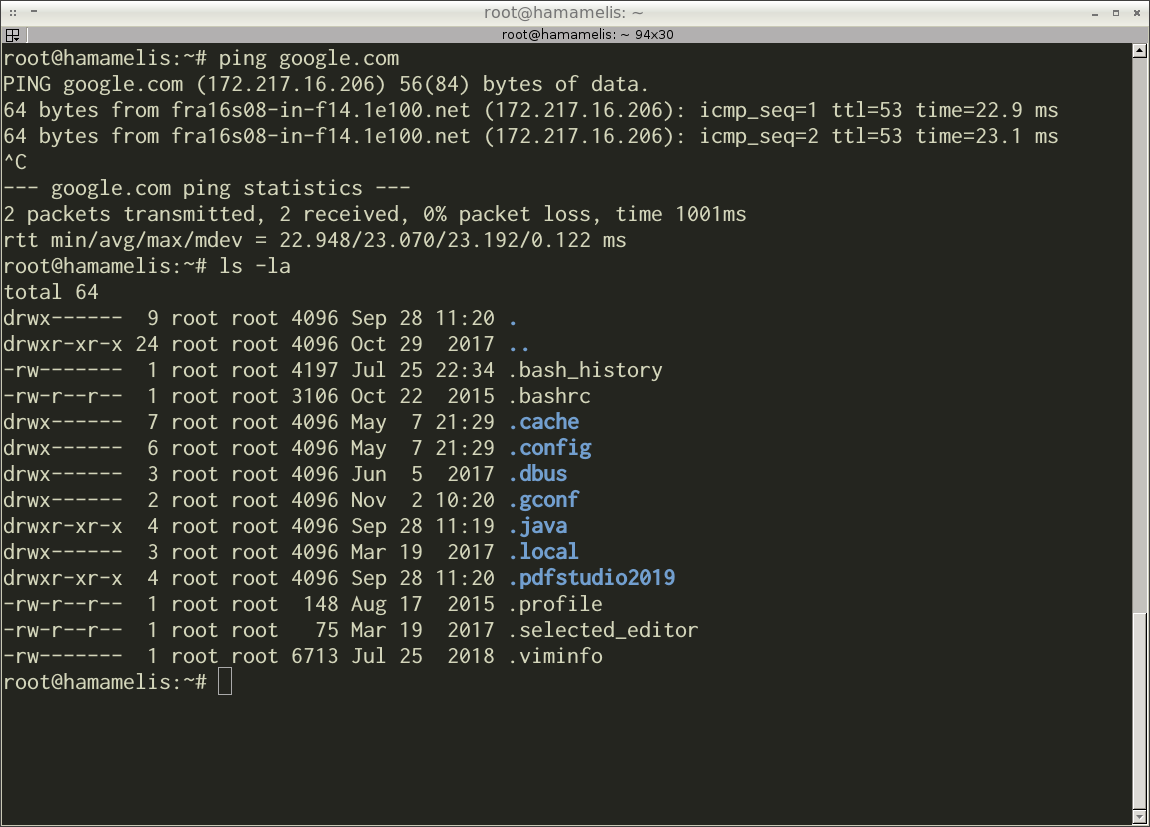

Teletype (TTY) became a prototype of a device for interactive work with a computer. The original idea behind this device was to connect two of them via wires. It allows users on both sides to send each other text messages. One user types the message on the keyboard. Then his device transmits the keystrokes to the receiver. When the teletype on the other side receives data, it prints the text on paper.

Figure 1-6 shows the Model 33 teletype. It was one of the most popular devices in the 1960s.

Computer engineers connected the teletype to the computer. This solution allowed the user to send text commands to the machine and receive results. Such a workflow became known as a command-line interface (CLI).

Teletype uses the printer as an output device. It works very slow and requires around 10 seconds to print a single line. The next step of developing the user interface was replacing the printer with the monitor. This increased the data output speed several times. The new device with a keyboard and monitor was called the terminal. It replaced teletypes in the 1970s.

Figure 1-7 shows a modern command-line interface. You can see the terminal emulator application there. This application emulates the terminal device for the sake of compatibility. It allows you to run programs that work with the real terminal only. The emulator application in Figure 1-7 is called Terminator. The Bash command-line interpreter is running in the Terminator window. The window displays the results of the ping and ls programs.

The command-line interface is still in demand today. It has several advantages over the graphical interface. For example, CLI does not require as many resources as GUI. CLI runs reliably on low-performance embedded computers as well as on powerful servers. If you use CLI to access the computer remotely, you can use a low bandwidth communication channel. The server will receive your commands in this case.

The command-line interface has some disadvantages. Learning to use CLI effectively is hard and takes time. You have to remember around a hundred commands. Each command has several modes that change its behavior. Therefore, you should keep in mind these modes too. It takes some time to remember at least a minimum set of commands for daily work.

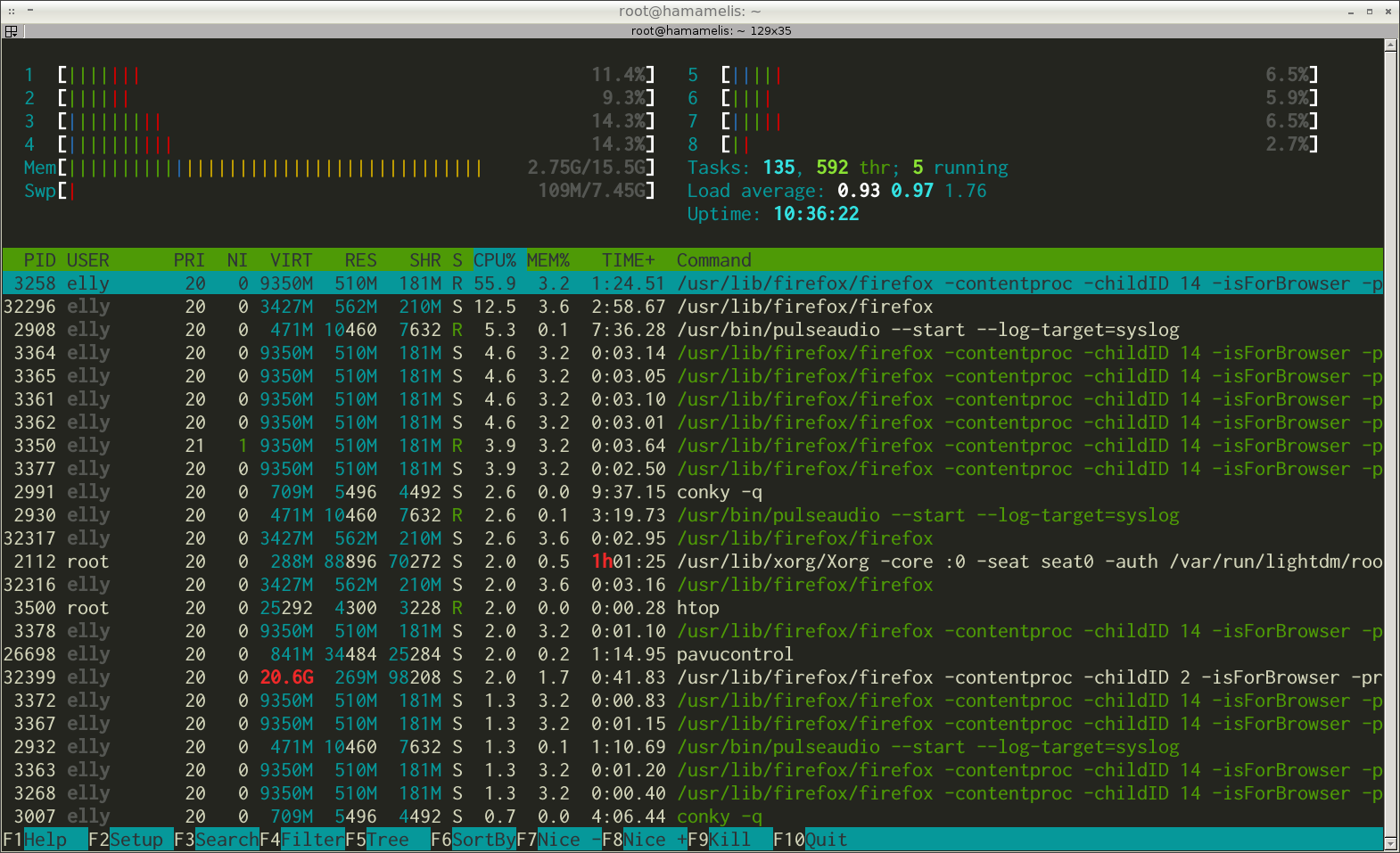

There is an option to make the command-line interface more user-friendly. You can give a hint to the user about available commands. It was done in the text-based interface (TUI). The interface uses box-drawing characters along with alphanumeric symbols. The box-drawing characters display the graphic primitives on the screen. Primitives are lines, rectangles, triangles, etc. They guide the user about the available actions he can do with the application.

Figure 1-8 shows a typical text-based interface. There is an output of system resource usage by the htop program.

The further performance gain of computers allowed OS developers to replace box-drawing characters with real graphic elements. There are examples of such elements: windows, icons, buttons, etc. It was a moment when the full-fledged graphical interface came. Modern OSes provide this kind of interface.

The first GUI appeared in the Xerox Alto minicomputer (see Figure 1-10). It was developed in the research center Xerox PARC in 1973. However, the graphical interface did not spread widely until the 1980s. It happens because GUI requires a lot of memory and high computer performance. PCs with such features were too expensive for ordinary users at that time.

Apple produced the first relatively cheap PC with GUI in 1983. It was called Lisa.

Figure 1-9 demonstrates the Windows GUI. You can see the desktop. There are windows of three applications there. The applications are Explorer, Notepad and Calculator. They work in parallel.

Families of OSes

There are three families of OSes that dominate the market today. Here are these families:

The term “family” means several OS versions that follow the same architectural solutions. Therefore, most functions in these versions are implemented in the same way.

The developers of the OS family follow the same architecture. They do not offer something fundamentally new in the upcoming versions of their product. Why?

Actually, changes in modern OSes happen gradually and slowly. The reason for this is a backward compatibility problem. This compatibility means that newer OS versions provide the features of older versions. Most existing programs require these features for their work. You can suppose that backward compatibility is an optional requirement. However, it is a severe limitation for software development. Let’s find out why it is.

Imagine that you wrote a program for Windows and sell it. Sometimes users meet errors in the program. You receive bug reports and fix them. Also, you add new features from time to time.

Your business goes well until the new Windows version comes. Let’s assume that Microsoft has changed its architecture completely. Therefore, your program does not work on the new OS version. This leads users of your program to the following choice:

- Update Windows and wait for the new version of your program that works there.

- Do not update Windows and continue to use your program.

If users need your program for daily work, they refuse the Windows update. Using the program is more important than getting new OS features.

We know that Microsoft has changed the Windows architecture completely. It means that you should rewrite your program from scratch. Now count all the time that you have spent fixing bugs and adding new features. You should repeat all this work as soon as possible. Most likely, you will give up this idea. Then your users should stay with the old Windows version.

Windows is a very popular and widespread OS. It means that there are many programs like yours. Their developers will come to the same decision as you. As a result, nobody updates to the new Windows version. This situation demonstrates the backward compatibility problem. This problem forces OS developers to be careful with changing their products. The best solution for them is to make a family of similar OSes.

There is a significant influence of user applications on OS development. For example, Windows and IBM computers owe their success to a table processor Lotus 1-2-3. You need both IBM PC and Windows to lunch Lotus 1-2-3. For the sake of Lotus 1-2-3, users bought both the computer and OS. The specific combination of the hardware and software is called the computing platform. The popular application, which brings the platform to the broad market, is called killer application.

The tabular processor VisiCalc was another killer application. It promoted the distribution of the Apple II computers. In the same way, free compilers for C, Fortran and Pascal languages help Unix OS to become popular in university circles.

There was the killer application behind each of the modern OS families. This application gave these OSes the initial success. Further distribution of the OS happened thanks to the network effect. This effect means that developers tend to choose the most widespread computing platforms for their new applications.

What are the differences between the OS families? Windows and Linux are remarkable because they do not depend on the hardware. It means that you can install them on any modern PC or laptop. macOS runs on Apple computers only. If you want to use macOS on different hardware, you would need the unofficial modified version of OS.

Hardware compatibility is an example of the design decision of the OS development. There are many such decisions. Together they define the features and design of each OS family.

There is one more important point for software development besides the OS design. OS dictates the infrastructure for the programmer. The infrastructure means development tools. Examples of these tools are IDE, compiler, build system. Tools together with OS API impose some design decisions for the applications. It leads to a specific culture for program development. Please keep in mind that you should develop applications differently for each OS. Take it into account when you design your programs.

Let’s consider the origins of software development cultures for Windows and Linux.

Windows

Windows is proprietary software. The source code of such software is unavailable for users. You cannot read or modify it as you want. In other words, there is no legal way to know about proprietary software more than its documentation tells you.

If you want to install Windows on your computer, you should buy it from Microsoft. However, manufacturers of computers pre-install Windows on their devices often. In this case, the final cost of the computer includes the price of the OS.

The target devices for Windows are relatively cheap PCs and laptops. Many people can buy such a device. Therefore, there is a huge market of potential users. Microsoft tends to keep its competitive edge in this market. The best way to reach it is to prevent appearing of Windows analogs with the same features from other companies. For reaching this goal, Microsoft takes care of protecting its intellectual property. The company does it in both technical and legal ways. An example of legal protection is the user agreement. It prohibits you to explore the internals of the OS.

The Windows OS family has a long history. Also, it is popular and widespread. It leads many developers to chose this OS as the target for their applications. However, the Microsoft company has developed the first Windows applications on its own. An example is the package of office programs Microsoft Office. Such applications became a standard to follow for other developers.

Microsoft followed the same principle when developing both Windows and applications for it. It is a secrecy principle:

- Source codes are not available to users.

- Data formats are undocumented.

- Third-party utilities do not have access to software features.

The goal of these decisions is to protect intellectual property.

Other software developers have followed the example of Microsoft. They stuck with the same philosophy of secrecy. As a result, their applications are self-contained and independent of each other. The formats of their data are encoded and undocumented.

If you are an experienced computer user, you immediately recognize a typical Windows application. It has a window with control elements like buttons, input fields, tabs, etc. You manipulate some data using these control elements. Examples of data are text, image, sound record, video. When you are done, you save your results on the hard disk. You can open it again in the same application. If you write your own Windows program, it will look and work similarly. This succession of solutions is called the development culture.

Linux

Linux has borrowed most of the ideas and solutions from the Unix. Both OSes follow the set of standards that is called POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface). POSIX defines interfaces between applications and the OS. Linux and Unix got the same design because they follow the same standard. We should have a look at the Unix origins to get this design.

The Unix appeared in the late 1960s. Two engineers from the Bell Labs company have developed it. Unix was a hobby project of Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie. In their daily work, they developed the Multics OS. It was a joint project of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), General Electric (GE) and Bell Labs. General Electric planned to use Multics for its new computer GE-645. Figure 1-11 demonstrates this machine.

The Multics developers have invented several innovative solutions. One of them was time-sharing. It allows several users to work with the computer at the same time. Multics uses the multitasking concept to share resources among all users.

Because of many innovations and high requirements, Multics turned out to be too complicated. The project consumed more time and money than it was planned. This was a reason why Bell Labs left the project.

The Multics project was interesting from a technical point of view. Therefore, many Bell Labs engineers wanted to continue working on it. Ken Thompson was one of them. He decided to create his own operating system for the computer GE-645. Thompson started to write the system kernel and duplicated some Multics mechanisms. However, General Electric demanded the return of its GE-645 soon. Bell Labs has received this computer on loan only. As a result, Thompson lost a hardware platform for his development.

When working on the Multics analog, Thompson had a pet project to create a computer game. It was called Space Travel. He launched the game on the past generation computer GE-635 from General Electric. It had the GECOS OS. GE-635 consisted of several modules. Each module was a cabinet with electronics. The overall computer cost was about $7500000. Bell Labs engineers actively used this machine. Therefore, Thompson was rarely able to work with it to develop his game.

The limited access to the GE-635 machine was a problem. Therefore, Thompson decided to port his game to a relatively inexpensive and rarely used computer PDP-7 (see Figure 1-12). Its cost was about $72000. When doing that, Thompson met one problem. Space Travel used the features of the GECOS OS. The software of PDP-7 did not provide such features. Thompson was joined by his colleague Dennis Ritchie. They implemented GECOS features for PDP-7 together. It was a set of libraries and subsystems. Over time, these modules were developed into a self-sufficient OS. It was called Unix.

Thompson and Ritchie were not going to sell Unix. Therefore, they never had a goal to protect their intellectual property. They developed Unix for their own needs. Afterward, they distributed it for free with the source code. Everyone could copy and use this OS. It was reasonable because the first Unix users were Bell Labs employees only.

Unix became popular among Bell Labs employees. Thompson and Ritchie presented the OS at the Symposium on Operating Systems Principles conference. Then they got a lot of requests for the system. However, Bell Labs belonged to AT&T company. Therefore, Bell Labs did not have the right to distribute any software on its own.

AT&T noticed the new perspective OS. The company started to sell its source code to universities for $20000. Thus, university circles got a chance to improve and develop Unix.

Linus Torvalds met Unix when he had studied at the University of Helsinki. Unix encouraged him to create his own OS called Linux. It was not a pet project for fun. Torvalds met a practical problem. He needed a Unix-compatible OS for his PC to do university tasks at home. Such OS was not available at that moment.

At the University of Helsinki, students performed study assignments using the MicroVAX computer running Unix. Many of them had PCs at home. However, there was no Unix version for PC. The only Unix alternative for students was Minix OS.

Andrew Tanenbaum developed Minix for IBM PCs with Intel 80268 processors in 1987. He created Minix for educational purposes only. This was a reason why he refused to apply changes to his OS for supporting modern PCs. Tanenbaum was afraid that his system becomes too complicated. Then he cannot use it for teaching students.

Torvalds had a goal to write a Unix-compatible OS for his new IBM computer with Intel 80386 processor. He used Minix OS for development but did not import any part of it to Linux. Like the Unix creators, Torvalds had no commercial interests and was not going to sell his software. He developed the OS for his own needs and wanted to share it with everyone. Linux became free in this way. Torvalds decided to distribute it with source code for free via the Internet. This decision made Linux well known and popular.

Torvalds developed the kernel of OS only. The kernel provides memory management, file system, peripherals drivers and processor time scheduler. However, users needed an interface to access the kernel’s features. It means that the Linux OS was not ready for use as it is.

The solution to the problem came from the GNU software project. Richard Stallman started this project at MIT in 1983. His idea was to develop the most necessary software for computers and make it free. The major products of the GNU project are the GCC compiler, glibc system library, system utilities and Bash shell. Torvalds included these products in his project and released the first Linux distribution in 1991.

The first versions of Linux did not have a graphical interface. The only way to interact with the system was a command-line shell. Some complex applications had a text interface, but they were the minority. Linux got a GUI in the middle of the 1990s. This interface was based on X Window System free software. X Window allowed developers to create graphical applications.

Unix and Linux evolved in very specific conditions. They differ from a typical cycle of commercial software development. These conditions made a unique development culture. Both systems developed in university circles. Computer science teachers and students used the OSes in daily work. They understood this software well. Therefore, they fixed software errors and added new features there willingly.

Let’s have a look at what is the Unix development culture. Unix users prefer to use highly specialized command-line utilities. You can find a tool almost for each specific task. Such tools are well written, tested many times and worked as efficiently as possible. However, all features of one utility are focused on one specific task. The utility is not universal software to cover most of your needs.

When you meet a complex task, there is no single utility to solve it. However, you can easily combine several utilities and solve your task this way. Such an interaction becomes available thanks to a clear data format. Most Unix utilities use the text data format. It is simple and self-explained. You can start working with it immediately.

The Linux development culture follows the Unix traditions. It differs from the standards that are adopted in Windows. Every application is monolithic and performs all its tasks by itself in the Windows world. The application does not rely on third-party utilities. The reason is the most software for Windows costs money and can be unavailable to the user. Therefore, each developer relies on himself. He cannot force the user to buy something extra to make the specific application working.

The software dependency looks different in Linux. Most of the utilities are free, interchangeable and accessible via the Internet. Therefore, it is natural that one program requires you to download and install a missing system component or another program.

The interaction of programs is crucial in Linux. Even monolithic graphical Linux applications usually provide a command-line interface. This way, they fit smoothly into the ecosystem. It leads that you can integrate them with other utilities and applications.

Suppose that you are solving a complex task in Linux. You should assemble a single computing process from a combination of highly specialized utilities. It means that you make a computation algorithm that can be complex by itself. Linux provides a tool for this specific task. The tool is called shell. Using the shell, you type commands and the system performs them. The first Unix shell appeared in 1979. It was called Bourne shell. Now it is deprecated. The Bash shell has replaced it in most Linux distributions. We will consider Bash in this book.

We have considered Linux and Windows cultures. You cannot give a preference to one or another. Comparing them causes endless disputes on the Internet. Each culture has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, the Window-style monolithic applications cope well the tasks that require intensive calculations. When you combine specialized Linux utilities for the same task, you get an overhead. The overhead happens because of launching many utilities and transferring data between them. This requires extra time. As a result, you wait longer to complete your task.

Today, we observe a synthesis of Windows and Linux cultures. Microsoft started to contribute to open-source projects: Linux kernel, the samba network protocol, PyTorch machine learning library, the Chromium web browser, etc. The company has released some of its projects with a free license: .NET Framework, PowerShell, VS Code IDE, etc.

On the other side, more and more commercial applications get ported to Linux: browsers, development tools, games, messengers, etc. However, their developers are not ready for changes that the Linux culture dictates. Such changes require too much time and effort. They also make it more challenging to maintain the product. Instead of one application, there are two: each platform has a different version. Therefore, developers port their applications without significant changes. As a result, you find more and more Windows-style applications on Linux.

One can argue about the pros and cons of this process. However, the more applications run on the specific OS, the more popular it becomes, thanks to the network effect.

Computer Program

We got acquainted with operating systems. They are responsible for starting and running computer programs. The program or application solves the user’s specific task. For example, a text editor allows you to write and edit documents.

A program is a set of elementary steps. They are called instructions. The computer performs these steps sequentially. It follows the strict order of actions and copes with complex tasks. Let’s consider how the computer launches and executes the program in detail.

Computer Memory

A hard disk stores all instructions of the program. If the program is relatively small and simple it fits a single file. Complex applications occupy several files.

Suppose that you have a single file program. When you launch it, the OS loads the file into the computer memory called RAM. Then the OS allocates a part of processor time for the new task. This way, the processor performs the program’s instructions at specified intervals.

The first step of launching a program is to load it into RAM. We should consider the computer memory internals to understand this step better.

The single unit of the computer memory is byte. The byte is the minimum amount of information that the processor can reference and load into its memory. However, the CPU can handle smaller amounts of data if you apply special techniques. You operate bits in this case. A bit is the smallest amount of information you cannot divide. You can imagine the bit as a single logical state. It has one of two possible values. There are several ways to interpret them:

- 0 or 1

- True or False

- Yes or No

- + or —

- On or Off.

Another way to imagine one bit is to compare it with a lamp switch. It has two possible states:

- The switch closes the circuit. Then the lamp is on.

- The switch opens the circuit. Then the lamp is off.

A byte is a memory block of eight bits. Here you can ask why do we need this packaging? CPU can operate a single bit, right? Then it should be able to refer to a specific bit in memory.

CPU cannot refer to a single bit. There are technical reasons for that. The primary task of the first computers was arithmetic calculations. For example, these computers calculated the ballistic tables. You should operate integers and fractional numbers to solve such a task. The computer does the same. However, a single bit is not enough to store a number in memory. Therefore, the computer needs memory blocks to store numbers. The bytes became such blocks.

Introducing bytes affected the architecture of processors. Engineers have expected that the CPU performs most operations over numbers. Therefore, they added a feature to load and process all bits of the number at once. This solution increased computers’ performance by order of magnitude. At the same time, loading of the single bit in the CPU happens rarely. Supporting this feature in hardware brings significant overhead. Therefore, engineers have excluded it from modern processors.

There is one more question. Why does a byte consist of eight bits? It was not always this way. The byte was equal to six bits in the first computers. Such a memory block was enough to encode all the English alphabet characters in upper case, numbers, punctuation marks and mathematical operations.

Six-bits encodings were insufficient for representing control and box-drawing characters. Therefore, these encodings were extended to seven bits in the early 1960s. The ASCII encoding appeared at that moment. It became the standard for encoding characters. ASCII defines characters for codes from 0 to 127. The maximum seven-bit number 127 limits this range.

Then IBM released the computer IBM System/360 in 1964. The size of a byte was eight bits in this computer. IBM chose this size for supporting old character encodings from the past projects. The IBM System/360 computer was popular and widespread. It led that eight-bit packaging became the industry standard.

Table 1-1 shows frequently used units of information besides bits and bytes.

| Title | Abbreviation | Number of bytes | Number of bits |

|---|---|---|---|

| kilobyte | KB | 1000 | 8000 |

| megabyte | MB | 1000000 | 8000000 |

| gigabyte | GB | 1000000000 | 8000000000 |

| terabyte | TB | 10000000000 | 8000000000000 |

Table 1-2 shows standard storage devices and their capacity. You can compare them using Table 1-1.

| Storage device | Capacity |

|---|---|

| Floppy disk 3.5” | 1.44 MB |

| Compact disk | 700 MB |

| DVD | up to 17 GB |

| USB flash drive | up to 2 TB |

| Hard disk drive | up to 16 TB |

| Solid State Drive | up to 100 TB |

We got acquainted with units of information. Now let’s get back to the execution of the program. Why does the OS load it into RAM? In theory, the processor can read the program instructions directly from the hard disk drive, right?

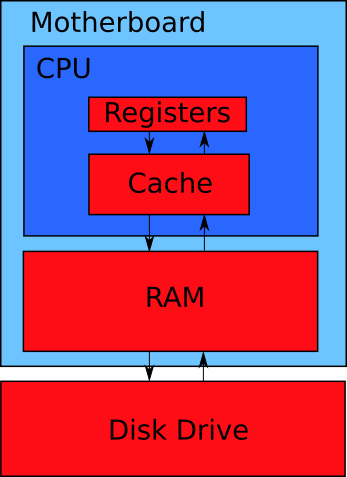

A modern computer has four levels of the memory hierarchy. Each level matches the red rectangle in Figure 1-13. Each rectangle match a separate device. The only exception is the CPU chip. It contains both registers and a memory cache. These are separate modules of the chip.

You see the arrows in Figure 1-13. They represent data flows. Data transfer occurs between adjacent memory levels.

Suppose that you want to process some data on the CPU. Then you should load these data to its registers. This is the only place where the processor can take data for calculations. If the CPU needs something from the disk drive, the following data transfers happen:

- Disk drive -> RAM

- RAM -> Processor cache

- Processor cache -> Processor registers

When the CPU writes data back to the disk, it happens in the reverse order of steps.

Data storage devices have the following parameters:

- Access speed defines the amount of data that you can read or write to the device per unit of time. Units of measure are bytes per second (Bps).

- Capacity is the maximum amount of data that a device can store. The units are bytes.

- Cost is a price of a device concerning its capacity. The units are dollars or cents per byte or bit.

- Access time is the time between the moment when the processor needs some data from the device and when it receives them. Units are clock signals of the CPU.

These parameters vary for devices on each level of the memory hierarchy. Table 1-3 shows the ratio of parameters for modern storage devices.

| Level | Device | Capacity | Access speed | Access time | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CPU registers | up to 1000 bytes | - | 1 tick | - |

| 2 | CPU cache | from one KB to several MB | from 700 to 100 GBps | from 2 to 100 cycles | - |

| 3 | RAM | dozens of GB | 10 GBps | up to 1000 clock cycles | $10-9/byte |

| 4 | Disk drive (hard drive or solid drive) | several TB | 2000 Mbps | up to 10000000 cycles | $10-12/byte |

Table 1-3 raises questions. You can read the data from the disk drive at high speed. Why is there no way to read these data to the CPU registers directly? Actually, you can do it, but it leads to a significant performance drawback.

The high speed of accessing a memory storage is not so crucial for performance in practice. The critical parameter here is the access time. It measures the idle time of the CPU until it receives the required data. You can measure this idle time in clock signals or cycles. Such a signal synchronizes all operations of the processor. The CPU requires roughly from 1 to 10 clock cycles to execute one instruction of the program.

High access time can cause serious performance issues. For example, suppose that the CPU reads the program instructions directly from the hard disk. The problem happens because CPU registers have a small capacity. There is no chance to load the whole program from the hard disk to the registers. Therefore, when the CPU did one part of the program, it should load the next one. This loading operation takes up to 10000000 clock cycles. It means that loading data from the disk takes a much longer time than processing them. The CPU spends most of the time idling. The memory hierarchy solves exactly this problem.

Let’s consider data flow between memory levels by example. Suppose that you launch a simple program. It reads a file from the hard disk and displays its contents on the screen. Reading data from the disk happens in several steps. The hardware does them.

The first step is reading data from the hard disk into the RAM according to Figure 1-13. The next step is loading data from RAM to the CPU cache. There is a sophisticated caching mechanism. It guesses the data from RAM that the CPU requires next. This mechanism reduces the access time to the data and decreases the idle time of the CPU.

When data comes to the CPU chip, it manages them on its own. The processor reads the required data from the cache to registers and manipulates them. The program instructions reach the CPU the same way as the data.

The program displays data on the screen in our example. It should call the corresponding API function for that. Then the system library changes the screen picture. The CPU does the actual work here. It loads the instructions of the system library and the video card driver. Then the CPU applies these instructions to the data in its registers. This way, the video card driver displays the data on the screen.

The required data may absent in the specific memory level. Here are few examples. Suppose that the CPU needs data to process them in the video driver code. If these data are in the CPU cache but not in the registers, the processor waits for 2-100 clock cycles to get them. If data are in the RAM, the CPU’s waiting time increases by order of magnitude up to 1000 cycles.

Our program can display both small and big files. Some big file does not fit the RAM. Then the RAM contains only part of it. The CPU can require the missing file part. In this case, the CPU idle time increases by four orders of magnitude up to 10000000 clock cycles. For comparison, the processor could execute about 1000000 program instructions instead of this idle time. This is really a lot.

Both CPU and disk drives use hardware caching mechanisms. The idea of caching for disk drives is to store some data in the small and fast access memory. It speeds up reading and writing blocks of data. There are caching mechanisms on the software level too. They are parts of the OS in most cases.

All caching mechanisms increase a computer’s performance significantly. When such a mechanism makes a mistake, it leads to the CPU idle. This mistake is called cache miss. Any cache miss is expensive from the performance point of view. Therefore, remember the memory hierarchy and caching mechanisms. Consider them when developing algorithms. Some algorithms and data structures cause more cache misses than others.

The storage devices with lower access times are placed closer to the CPU. Figure 1-14 demonstrates this principle. For example, registers and cache is the internal CPU memory. They are part of the processor’s chip.

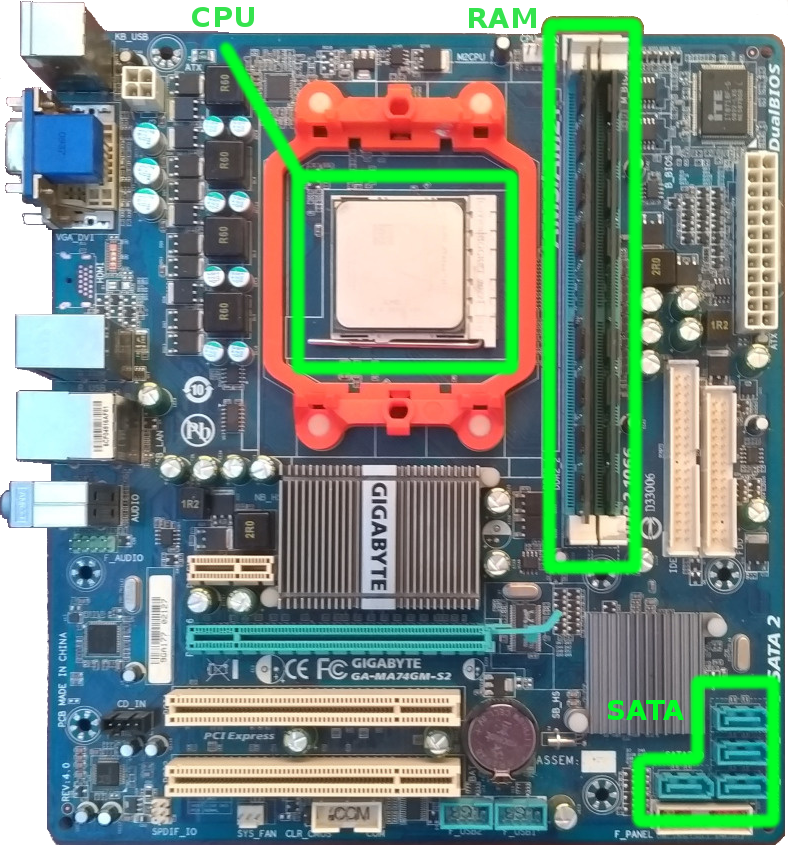

Both CPU and RAM are two chips that are plugged into the motherboard near each other. The high-frequency data bus connects them. This data bus provides low access time.

The motherboard is the printed circuit board that connects computer components. You can plug in some chips right into the motherboard. However, there are devices that you should connect via cables there. The disk drive is an example of such a device. It connects to the motherboard via a relatively slow interface. There are several standards for such an interface: ATA, SATA, SCSI, PCI Express.

The old motherboard models have an embed chip that transfers data between CPU and RAM. This chip is called northbridge. Thanks to improving technologies for chip manufacturing, the CPUs take northbridge’s functions since 2011.

The southbridge is another motherboard’s chip. It presents there nowadays. The southbridge transfers data between RAM and devices that are connected via slow interfaces like PCI, USB, SATA, etc.

Machine code

Suppose that the OS has loaded the contents of an executable file into RAM. This file contains both instructions and data of the program. Examples of data are text strings, box-drawing characters, predefined constants, etc.

Program instructions are written in machine code. This code consists of commands that processor performs one by one. A single instruction is an elementary operation on the data from the CPU registers.

The CPU has logical blocks for executing each type of instruction. The available blocks determine the operations that the CPU can perform. If the processor does not have an appropriate logical block to accomplish a specific instruction, it combines several blocks to do this job. The execution takes more clock cycles in this case.

When the OS has loaded the program instructions and its data into RAM, it allocates the CPU time slots for that. The program becomes a computing process or process since this moment. The process means the running program and the resources it uses. Examples of the resources are memory area and OS objects.

How do the program instructions look like? You can see them using the special program for reading and editing executable files. Such a program is called hex editor. The editor represents the program’s machine instructions in hexadecimal numeral system. The actual contents of the executable file is binary code. This code is a sequence of zeros and ones. The CPU receives program instructions and data in this format. The hex editor makes them easy to read for humans.

There are advanced programs to read machine code. They are called disassemblers. Disassembler translates the program instructions into assembly language. This language is more convenient for a human to read. You can get a better representation of the program using the disassembler than the hex editor.

If you take a specific number, it looks different in various numeral systems. The numeral system determines the symbols and their order to write a number. For example, binary allows 0 and 1 symbols only.

Table 1-4 shows matching of numbers in binary (BIN), decimal (DEC), and hexadecimal (HEX).

| Decimal | Hexadecimal | Binary |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0000 |

| 1 | 1 | 0001 |

| 2 | 2 | 0010 |

| 3 | 3 | 0011 |

| 4 | 4 | 0100 |

| 5 | 5 | 0101 |

| 6 | 6 | 0110 |

| 7 | 7 | 0111 |

| 8 | 8 | 1000 |

| 9 | 9 | 1001 |

| 10 | A | 1010 |

| 11 | B | 1011 |

| 12 | C | 1100 |

| 13 | D | 1101 |

| 14 | E | 1110 |

| 15 | F | 1111 |

Why do programmers use both binary and hexadecimal numeral systems? It is more convenient to use only one of them, right? We should know more about computer hardware to answer this question.

The binary numeral system and Boolean algebra are the basis of digital electronics. An electrical signal is the smallest portion of the information there. When you work with such signals, you need a way to encode them. Encoding means associating specific numbers with the signal states. The signal has two states only. It can present or absent. Therefore, the simplest way to encode the signal is to take the first two integers: zero and one. Then you use zero when there is no signal. Otherwise, you use the number one. Such encoding is very compact. You can use one bit to encode one signal.

The basic element of digital electronics is a logic gate. It converts electrical signals. You can implement the logic gate using various physical devices. Examples of such devices are an electromagnetic relay, vacuum tube and transistor. Each device has its own physics in the background. However, they work in the same way in terms of signal processing. This processing contains two steps:

- Receive one or more signals on the input.

- Transmit the resulting signal to the output.

The signal processing follows the rules of Boolean algebra. This algebra has an elementary operation for each type of logic gate. When you combine logic gates together, you can calculate the result using a Boolean expression. Combining logic gates provides a complex behavior. You need it if your digital device follows some non-trivial logic. For example, the CPU is a huge network of logic gates.

When you deal with digital electronics, you should apply the binary numeral system. This way, you convert signal states to logical values that Boolean algebra operates. Then you can calculate the resulting signals. The level of signals and logic gates is close to the computer hardware. You have to work on this level sometimes when programming. We can say that the hardware design dictates you to use the binary numeral system.

The binary numeral system is a language of hardware. Why do you need the hexadecimal system then? When you develop a program, you need decimal and binary systems only. Decimal is convenient for writing a general logic of the program. For example, you count repeating the same action in decimal.

You need the binary system when your program deals with computer hardware. For example, you send data to some device in binary format. There is one problem with binary. It is hard to write, read, memorize and pronounce the numbers in this system for humans. Conversion from decimal to binary takes effort. The hexadecimal system solves both problems of representing and converting numbers. It is a compact and convenient as the decimal system. At the same time, you can convert a number from hexadecimal to binary form easily.

Follow these steps to convert a number from binary to hexadecimal form:

- Split the number into groups of four digits. Start the splitting from the end of the number.

- If the last group is less than four digits, add zeros to the left side of the group.

- Use Table 1-4 to replace each four-digit group with one hexadecimal number.

Here is an example of converting the binary number 110010011010111:

1 110010011010111 = 110 0100 1101 0111 = 0110 0100 1101 0111 = 6 4 D 7 = 64D7

There are the answers for all exercises in the last section of the book. Check yourself there if you are unsure about your results.

Let’s come back to executing the program. The OS loads its executable file from the disk drive into RAM. Then the OS loads all libraries that the program requires. The special OS component does both these tasks. It is called loader. Thanks to preloading libraries, the CPU does not idle too much when the program accesses them. The instructions of the required library are already in RAM. Therefore, the CPU waits for a few hundred clock cycles to access them. When the loader finishes his job, the program becomes a process. The CPU executes it, starting from the first instruction.

Each machine code instruction is called opcode. The opcode dictates the CPU which logic gates it should apply for data in the specific registers. When the operation is done, the opcode specifies the register for storing the result. Opcodes have a binary format that is a natural language of the CPU.

While the program is running, its instructions, resources and required libraries occupy the RAM area. The OS clears this memory area when the program finishes. Then other applications can use it.

Source Code

Machine code is a low-level language for the representation of a program. This format is convenient for the processor. However, it is hard for a human to write a program in machine code. Software engineers developed the first programs this way. It was possible for early computers because of their simplicity. Modern computers are much more powerful and complex devices. Their programs are huge and have a lot of functions.

Computer engineers invented two types of special applications. They solve the problem of the machine code complexity. These applications are compilers and interpreters. They translate the program from a human-readable language into machine code. Compilers and interpreters solve this task differently.

Software developers use programming languages in their work nowadays. Compilers and interpreters take programs written in such languages and produce the corresponding machine instructions.

Humans use one of natural languages to communicate with each other. Programming languages are different from them. They are formal and very limited. Using a programming language, you can express only actions that a computer can perform. There are strict rules on how you should write these actions. For example, you can use a small set of words and combine them in specific orders. Source code is a text of the program you write in a programming language.

The compiler and interpreter process source code differently. The compiler reads the entire program text, generates machine instructions and saves them on a disk drive. The compiler does not execute the resulting program on its own. The interpreter reads the source code in parts, generates machine instructions and executes them immediately. The interpreter stores its results in RAM temporarily. When the program finishes, you lose these results.

Let’s consider how the compiler works step by step. Suppose that you have written the program. You saved its source code to a file on the hard disk. Then you run a compiler that fits the language you have used. Each programming language has the corresponding compiler or interpreter. The compiler reads your file, processes it and writes the resulting machine instructions in the executable file on a disk. Now you have two files: one with source code and one with machine instructions. Every time you change the source code file, you should generate the new executable file. You can run the executable file to launch your program.

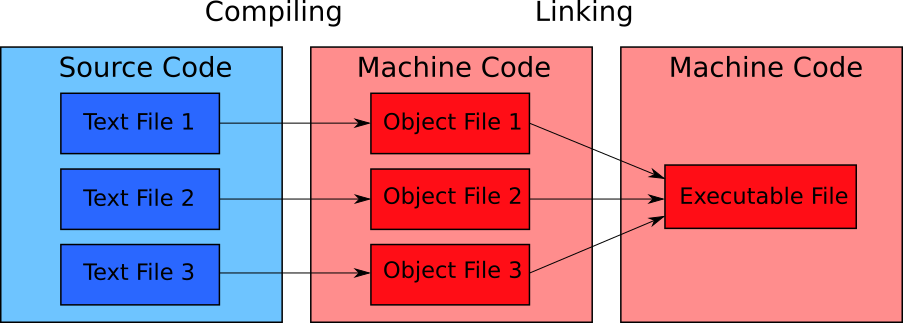

Figure 1-15 shows how the compiler processes a program written in C and C++ languages.

The compilation process consists of two steps. The compiler does the first step. The second step is called linking. The special program called linker performs it.

The compiler produces intermediate object files. The linker takes them and converts them to one executable file.

Why do you need two steps for compiling the source code? In theory, you can combine the compiler and linker into a single application. However, such a solution has several problems.

The limited RAM size causes the first problem. There is a common practice to split source code into several files. Each file matches a separate part of the program that solves the specific task. This way, you simplify your work with the source code. The compiler processes these files separately. It produces an object file for each source code file. They store the intermediate results of compilation.

If you combine the compiler and linker into one application, storing the intermediate results on the disk becomes a controversial decision. If you do it, you get the bottleneck because of slow disk operations. In theory, you can keep all data in RAM and get better performance. However, you cannot do it. When you deal with a big program, the compilation process consumes all your RAM and crashes.

Suppose that you have a combined compiler-linker that stores temporary files on the disk. In this case, storing temporary files brings the performance overhead. At the same time, you do not get any benefits from it. You avoided the RAM limitation this way. However, you can get the benefit by splitting the compiler and linker. Then you simplify both applications and make it cheaper to support them. The developers of compilers chose this way.

The second problem of the compiler-linker application is resolving dependencies. There are blocks of commands that call each other in the source code. Such references are called dependencies. Tracking them is the linker task.

When the compiler produces the object files, they contain machine code but not the source code. It is simpler for the linker to track dependencies in the machine code.

If you combine compiler and linker, you need extra passes through the whole program source code for resolving dependencies. The compiler needs much more time for a single pass over the source code than the linker for processing the machine code. Therefore, when you have the compiler and linker separated, you speed up the overall compilation process.

The program can call blocks of commands from the library. The linker process the library file together with the object files of your program in this case. The compiler cannot process the library. Its file contains machine code but not the source code. Therefore, the compiler does not understand it. Splitting the compilation into two steps resolves the task of using libraries too.

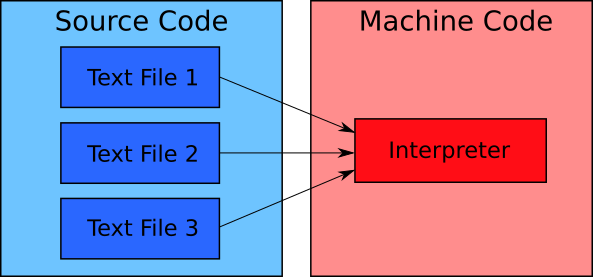

We have considered the basics of how the compiler works. Now suppose that you choose an interpreter instead to execute your program. You have the file with its source code on the disk drive. The file is ready for execution. When you run it, the OS loads the interpreter first. Then the interpreter reads your source code file into RAM and executes it line by line. The translation of source code commands to machine instructions happens in RAM. Some interpreters save files with an intermediate representation of the program to the disk drive. It speeds up the program execution if you restart it. However, you always need to run an interpreter first for executing your program.

Figure 1-16 shows the process of interpreting the program.

Figure 1-16 can give an idea that the interpreter works the same way as the compiler and linker combined into one application. The interpreter loads source code files into RAM and translates them into machine code. Why are there no problems with the RAM overflow and dependency resolution?

The interpreter avoids problems because it processes the source code differently than the compiler does. The interpreter processes and executes the program code line by line. Therefore, it does not store the machine code of the whole program in memory. The interpreter processes the parts of the source code file that it requires at the moment. When the interpreter executes them, it unloads these parts and frees the corresponding RAM area.

Interpreting the program looks more convenient for software development than compiling. However, it has some drawbacks.

First, all interpreters work slowly. It happens because every time you run the program, the interpreter should translate its source code to machine code. This process takes some time. You should wait for it. Another reason for the low performance of interpreters is disk operations. Loading the program’s source code from the disk drive into RAM causes the CPU to idle. It takes up to 10000000 clock cycles, according to Table 1-3.

Second, the interpreter itself is a complex program. It requires some portion of the computer’s hardware resources to launch and work. Therefore, the computer executes both interpreter and your program in parallel and shares resources among them. It is an extra overhead that reduces the performance of your program.

Interpreting the program is slow. Does it mean that compilation is better? The compiler generates an executable file with machine instructions. Therefore, you reach almost the program’s performance when you compile it or write machine instructions on your own. However, you pay for using the programming language at the compilation stage. A couple of seconds and a few megabytes of RAM are enough to compile a small program. When you compile a large project (for example, the Linux kernel), it takes several hours. If you change the source code, you should recompile the project and wait hours again.

Keep in mind the overhead of interpreters and compilers when choosing a programming language for your project. The interpreter is a good choice in the following cases:

- You want to develop a program quickly.

- You do not care about the program’s performance.

- You work on a small and relatively simple project.

The compiler would be better in the following cases:

- You work on a complex and large project.

- Your program should work as fast as possible.

- You want to speed up debugging of your program.

Both compilers and interpreters have an overhead. Does it make sense to discard a programming language and write a program in machine code? You do not waste your time waiting for compilation in this case. Your program works as fast as possible. These benefits sound reasonable. Please do not hurry with your conclusions.

One simple example helps you to realize all advantages of using a programming language. Listing 1-1 shows the source code written in C. This program prints the “Hello world!” text on the screen.

1 #include <stdio.h>2

3 int main(void)

4 {

5 printf("Hello world!\n");

6 }

Listing 1-2 shows the machine instructions of this program in the hexadecimal format.

1 BB 11 01 B9 0D 00 B4 0E 8A 07 43 CD 10 E2 F9