Bash Scripts

We have learned the basics of how to operate the file system using the shell. It is time to apply our knowledge and come from the standalone commands to programs. These programs written in Bash are called scripts. We will learn how to write them.

Development Tools

You have used the interactive mode of Bash in the previous chapter. The workflow of this mode looks like this:

- You type a command in the terminal window.

- The Bash process loads your command in RAM.

- The interpreter executes the command.

- Bash removes your command from RAM.

If you want to write a program, RAM is not the appropriate place to store it. This is a temporary memory. Whenever you shut down the computer, RAM is cleared.

When you write a program, you should store it on the disk drive. The disk drive is long-term information storage. Then you need a special program to create and edit source code files. This program is called a source code editor.

Let’s consider source code editors that work well with Bash.

Source Code Editor

Potentially, you can write Bash scripts in any text editor. Even the standard Windows application called Notepad can work this way. However, text editors are inconvenient for writing the source code. Notepad does not have any features for doing that. Meanwhile, these features increase your productivity significantly.

Today you can find plenty of free and proprietary source code editors. Some of them are more widespread than others. The popularity of the editor does not mean that it fits you perfectly. You should try several programs and choose one that you like.

Here there is a list of three popular source code editors. You can start with them. If no one fits you, please look for alternatives on the Internet.

Notepad++ is a fast and minimalistic source code editor. It is available for free. You can use it on Windows only. If your OS is macOS or Linux, please consider other editors. The latest Notepad++ version is available on the official website.

Sublime Text is a proprietary cross-platform source code editor. Cross-platform means that the program runs on several OSes and hardware configurations. Sublime Text works well on Windows, Linux and macOS. You can use it for free without buying a license. Download the editor on the official website.

Visual Studio Code is a free cross-platform source code editor from Microsoft. It works on Windows, Linux and macOS. You do not need to buy a license for using the editor. Download it on the official website.

All three editors have the following features for working with source code:

- Syntax highlighting.

- Autocomplete.

- Support of commonly used character encodings.

It is possible to edit the source code without these features. However, they make it easier to read and edit the program. They also help you to get used to the Bash syntax.

Launching the Editor

There are several ways to run the source code editor. The first option is using the GUI of your OS. Launch the editor via the Start menu or the desktop icon. It is the same way you run any other program.

The second option is using the command-line interface. This approach is more convenient in some cases. Here is an example of when you would need it. You call the find utility for searching several files. You can pass the find output to the source code editor input and open all found files. It is possible because most modern editors support CLI.

There are three ways to run an application in Bash:

- By the name of the executable.

- By the absolute path.

- By the relative path.

The first approach is the most convenient. You need to add the installation path of the application to the PATH variable. Then Bash can find the program’s executable when you call it.

Let’s consider how to run the Notepad++ editor by the executable name. The program has the following installation path by default:

When you work in the MSYS2 environment, the Notepad++ installation path looks like this:

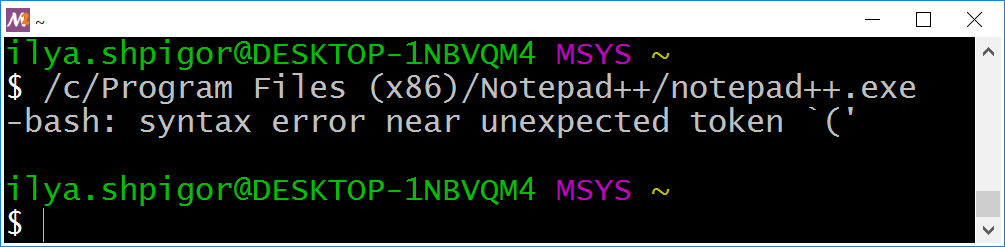

Try to run the editor using this absolute path. Figure 3-1 shows that it does not work. Bash reports about the syntax error in this case.

This command has several problems. We will investigate them one by one. The cd Bash built-in can give you the first hint about what is going wrong. Call cd this way:

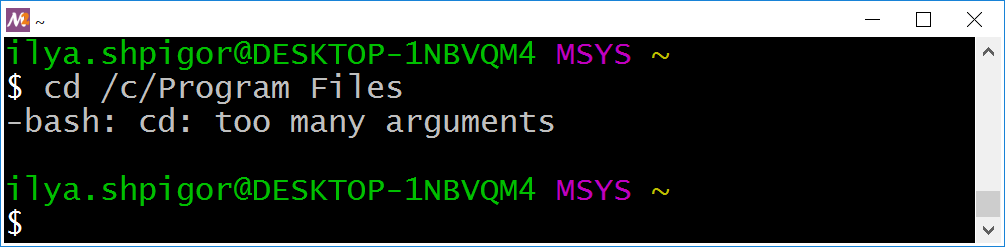

cd /c/Program Files

Figure 3-2 shows the result.

cd commandBash complains that you have passed too many parameters to cd. This command expects only one parameter, which is a path. It looks like you provided two paths instead of one here. This mistake happens because of the word splitting mechanism. Bash separated the path by the space into two parts: “/c/Program” and “Files”.

You have two option to suppress the word splitting mechanism:

1. Enclose the path in double quotes:

cd "/c/Program Files"

2. Escape all spaces using the backslash:

cd /c/Program\ Files

When you suppress word splitting, Bash executes the cd command properly.

Now try to navigate the /c/Program Files (x86) path. The following command does not work:

cd /c/Program Files (x86)

We found out that the issue happens because of word splitting. You can suppress it by escaping the spaces this way:

cd /c/Program\ Files\ (x86)

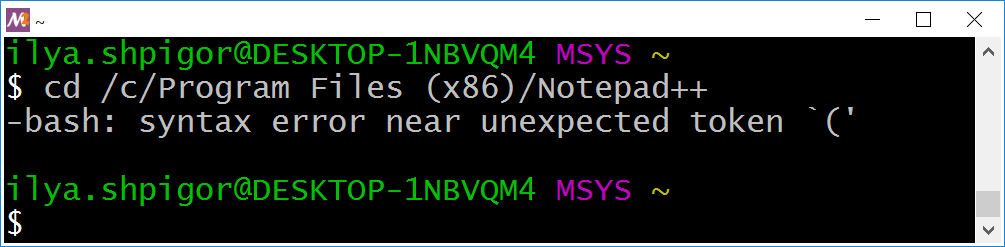

Figure 3-3 shows that this command still fails.

cd commandThis is the same error message as Bash has printed when launching Notepad++ in Figure 3-1. This problem happens because of the parentheses. They are part of the Bash syntax. It means that the shell treats them as a language construct. We met this problem when grouping conditions of the find utility. Escaping or double quotes solves this issue too. Here are possible solutions for our case:

1 cd /c/Program\ Files\ \(x86\)

2 cd "/c/Program Files (x86)"

Using double quotes is simpler than escaping. Apply them to launch the Notepad++ this way:

"/c/Program Files (x86)/Notepad++/notepad++.exe"

Now Bash launches the editor properly.

Launching Notepad++ by the absolute path is inconvenient. You should type a long command in this case. Launching the editor by the name of the executable is much better. Let’s change the PATH Bash variable for making that work.

Add the following line at the end of the ~/.bash_profile file:

PATH="/c/Program Files (x86)/Notepad++:${PATH}"

Restart the MSYS2 terminal. Now the following command launches Notepad++:

There is one more option to launch the editor from the shell. Instead of changing the PATH variable, you can declare an alias. The alias is a Bash mechanism. It replaces the command you typed with another one. This way, you can abbreviate long lines.

We have the following command for launching Notepad++:

"/c/Program Files (x86)/Notepad++/notepad++.exe"

Let’s declare the alias for this command. The alias Bash built-in does this job. Call it this way for our example:

alias notepad++="/c/Program\ Files\ \(x86\)/Notepad++/notepad++.exe"

This command declares the alias with the “notepad++” name. Now Bash replaces the “notepad++” command by the absolute path to the Notepad++ executable.

Using the alias has one problem. You should declare it whenever launching the terminal window. There is a way to automate this declaration. Just add our alias command at the end of the ~/.bashrc file. Bash executes this file at every terminal startup. Then you get declared alias in each new terminal window.

Now you can open the source code files in Notepad++ using the shell. Here is an example to open the test.txt file:

If the test.txt file does not exist, Notepad++ shows you the dialog to create it.

Background Mode

Suppose that you run a GUI application in the terminal window. Then you cannot use this window for typing the Bash commands. The GUI program controls it and prints the diagnostic messages there. The terminal window becomes available again when the application finishes.

You can run the GUI application in the background mode. Then the terminal window stays available, and you can use it normally.

Add the ampersand & at the end of a Bash command to launch it in the background mode. Here is an example:

&

After this command, you can type text in the terminal window. The only problem is the error messages from Notepad++. The editor still prints them here. They make it inconvenient to use this terminal window.

You can detach the running GUI application from the terminal window completely. Do it with the disown Bash built-in. Call disown with the -a option this way:

1 notepad++ test.txt &

2 disown -a

Now Notepad++ does not print any messages in the terminal. The disown call has one more effect. It allows you to close the terminal window and keep the editor working. Without the disown call, Notepad++ finishes when you close the terminal.

You can combine Notepad++ and disown calls into one command. It looks like this:

& disown -a

The -a option of the disown command detaches all programs that work in the background. If you skip this option, you should specify the process identifier (PID) of the program to detach. PID is a unique number that OS assigns to each new process.

Suppose that you want to call disown for the specific program. You should know its PID. Bash prints the PID of the background process when you launch it. Here is an example:

&

[1] 600

The second line has two numbers. The second number 600 is PID. The first number “[1]” is the job ID. You can use it to switch the background process to the foreground mode. The fg command does it this way:

fg %1

If you want to detach the Notepad++ process from our example, call disown this way:

disown 600

If you want to list all programs that work in the background, use the jobs Bash built-in. When you call it with the -l option, it prints both job IDs and PIDs. Use it this way:

jobs -l

This command lists all background processes that you have launched in the current terminal window.

You can call Notepad++ and detach it from the terminal in a single command. In this case, you should use the special Bash variable called $!. It stores the PID of the last launched command. Pass this PID to the disown call, and you are done. Here is an example of how to apply this approach:

& disown $!

Why Do We Need Scripts?

We learned how to write complex Bash commands using pipelines and logical operators. The pipeline combines several commands into one. You get a linear sequence algorithm this way. If you add logical operators there, you get the conditional algorithm. These operators allow you to handle special cases and choose a proper reaction for them.

The shell command that implements the conditional algorithm can be as complicated as a real program. What is the difference between them? Why do we need scripts that are Bash programs? Let’s figure out answers to these questions.

Backup Command

We need an example to consider Bash scripts features. Let’s write the command that creates a backup of your photos on the external hard drive. The command consists of two actions: archiving and copying.

Suppose that you store all your photos in the ~/photo directory. The mount point of the external drive is /d. Then the following command creates an archive of the photos on the external drive:

&& cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d

Here the logical AND connects the archiving and copying commands. Therefore, the cp call happens only when the bsdtar utility succeeds. This utility creates an archive called photo.tar.bz2. It contains all files of the ~/photo directory.

Suppose that you run the backup command automatically. For example, it launches every day by schedule. If some error happens, you do not have a chance to read its message. You need a log file to get this possibility. Here is an example of the bsdtar call that writes its status to the file:

1 bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 ~/photo &&

2 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

3 echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt

You can split a Bash command into multiple lines. There are two ways for doing that:

- Add the line break right after the logical operator (&& or ||).

- Add the line break after the backslash .

We applied the first option in the last bsdtar call. The second option looks like this:

1 bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 ~/photo \

2 && echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt \

3 || echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt

You would need the status of the cp call as well. Therefore, we should write it to the log file. Here is the command for that:

1 cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

2 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

3 echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

Now we can combine the bsdtar and cp calls into a single command. The logical AND should connect these calls. The straightforward solution looks like this:

&&

echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt &&

cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

Let’s check if this command works correctly. We can replace each command call with a Latin letter. Then we get a convenient form of the Boolean expression. The expression looks like this:

&& O1 || F1 && C && O2 || F2

The “B” and “C” letters represent the bsdtar and cp calls. “O1” is the echo call that prints “bsdtar - OK” line in the log file. “F1” is the echo call for printing “bsdtar - FAIL” line. Similarly, “O2” and “F2” are the commands for logging the cp result.

If the bsdtar call succeeds, the “B” operand of our expression equals “true”. Then Bash performs the sequence of the following steps:

- B

- O1

- C

- O2 or F2

If the bsdtar fails, the “B” operand equals false. Then Bash does the following steps:

- B

- F1

- C

- O2 or F2

It means that the shell calls the cp utility even when the archiving fails. It does not make sense.

Unfortunately, the bsdtar utility makes things even more confusing. It creates an empty archive if it cannot access the target directory or files. Then the cp utility copies the empty archive successfully. These operations lead to the following output in the log file:

1 bsdtar - FAILS

2 cp - OK

Such output confuses you. It does not clarify what went wrong.

Here is our expression again:

&& O1 || F1 && C && O2 || F2

Why does Bash call the cp utility when bsdtar fails? It happens because the echo command always succeeds. It returns zero code, which means “true”. Thus, the “O1”, “F1”, “O2” and “F2” operands of our expression are always “true”.

Let’s fix the issue caused by the echo call exit code. We should focus on the bsdtar call and corresponding echo commands. They match the following Boolean expression:

&& O1 || F1

We can enclose the “B” and “O1” operands in brackets this way:

(B && O1) || F1

It does not change the expression’s result.

We got a logical OR between the “(B && O1)” and “F1” operands. The “F1” operand always equals “true”. Therefore, the whole expression is always “true”. The value of “(B && O1)” does not matter. We want to get another behavior. If the “(B && O1)” operand equals “false”, the entire expression should be “false”.

One possible solution is inverting the “F1” operand. The logical NOT operator does that. We get the following expression this way:

Let’s check the behavior that we got. If the “B” command fails, Bash evaluates “F1”. It always equals “false” because of negation. Then Bash skips the “C” and “O2” commands. It happens because there is a logical AND between them and “F1”. Finally, Bash comes to the “F2” operand. The shell needs its value. Bash knows that the LHS operand of the logical OR equals “false”. Therefore, it needs to evaluate the RHS operand to deduce the result of the whole expression.

We can make the expression clearer with the following parentheses:

Now it is evident that Bash executes the “F2” action when the parenthesized expression equals “false”. Otherwise, it cannot deduce the final result.

The last command writes this output into the log file:

1 bsdtar - FAILS

2 cp - FAILS

This output looks better than the previous one. Now the cp utility does not copy an empty archive.

The current result still has room for improvement. Imagine that you extended the backup command. Then it contains 100 actions. If an error occurs at the 50th action, all the remaining operations print their failed results into the log file. Such output makes it complicated to find the problem. The better solution here is to terminate the command right after the first error occurred. Parentheses can help us to reach this behavior. Here is a possible grouping of the expression’s operands:

Let’s check what happens if the “B” operand is false. Then Bash executes the “F1” command. The negation inverts the “F1” result. Therefore, the entire LHS expression equals “false”. Here is the LHS expression:

Then the short-circuit evaluation happens. It prevents calculating the RHS operand of the logical AND. Then Bash skips all commands of the RHS expression. Here is the RHS expression:

We got the proper behavior of the backup command.

We can add one last improvement. The “F2” operand should be inverted. Then the whole expression equals “false” if the “C” command fails. Then the entire backup command fails if bsdtar or cp call fails. Inverting “F2” operand provides the proper non-zero exit status in the error case.

Here is the final version of our expression with all improvements:

Let’s come back to the real Bash code. The corrected backup command looks like this:

1 (bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 ~/photo &&

2 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

3 ! echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt) &&

4 (cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

5 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

6 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt)

We spent some time writing this command. However, another person would need much more time to read it and understand it correctly. It happens in programming often. This situation is a severe problem for big projects. Therefore, please train yourself to make your code clean and evident from the beginning. Code cleanliness is more important than a high speed of writing it.

Poor Technical Solution

Our backup command became long and complex after applying all improvements. Therefore, you should store it somewhere. Otherwise, you have to type the command in the terminal window each time. Typing is a bad idea because you can make a mistake or forget something.

Bash has an option to store frequently used commands. The history file saves everything you executed in the terminal. The file is unique for each user and has the ~ / .bash_history path. When you press the Ctrl+R keystroke in the terminal window, Bash calls the quick search over the history. You can quickly find the required command there.

Can you store the backup command permanently in the history file? This solution seems to be reliable and convenient. Please do not jump to conclusions. Let’s take a look at its possible problems.

First, the history file has a limited size. It saves 500 most recently executed commands by default. When this number exceeds, each new command overwrites the oldest one in the file. Therefore, you can lose the backup command accidentally.

You can think about increasing the capacity of the history file. Then the question arises. Which size would be enough? Whatever size you choose, there is a risk of exceeding it. This problem leads to the idea of making the history file unlimited. Then it saves all commands without overwriting anything.

It seems you find a way to store the backup command effectively. The history file with unlimited size does it. Could this decision lead to any problems?

Suppose you use Bash for a couple of years. All commands you executed during this time came to the .bash_history file. If you run the same command twice, it appears twice in the file. Therefore, the history size will reach hundreds of megabytes in two years. You do not need most of these commands. Only a small portion of them are significant for regular usage. It leads to inefficient use of your disk drive space.

You might argue that storing two hundred megabytes of the history file is not a problem for modern computers. Yes, it is true. However, there is another overhead that you missed. When you press Ctrl+R, Bash searches the command in the entire .bash_history file. The larger it is, the longer the search takes. Over time, you will wait several seconds, even using a powerful computer.

When the history file grows, the searching time increases. There are two reasons for that. First, Bash should process more lines in the history to find your request. Second, the file has many commands that have the same first letters. It leads you to type more letters after pressing Ctrl+R to find the right command. At some point, the history file search becomes inconvenient. That is the second problem with our solution.

What else could go wrong? Suppose that you got new photos. You placed them in the ~/Documents/summer_photo directory. Our backup command can handle the ~/photo path only. It cannot archive files from ~/Documents/summer_photo. Thus, you should write a new command for doing that. The complexity of extending features is the third problem of our solution.

You may have several backup commands for various purposes. The first one archives your photos. The second one archives your documents. It would be hard to combine them. You have to write the third command that includes all required actions.

We can conclude that a history file is a bad option for the long-term storage of commands. There is the same reason for all our problems. We misuse the history file mechanism. It was not intended for storing information permanently. As a result, we came up with a poor technical solution.

Everybody can come up with a poor technical solution. Professionals with extensive experience did such a mistake often. It happens for various reasons. The lack of knowledge played a role in our case. We got how Bash works in the shell mode. Then we applied this experience to the new task. The problem happened because we did not take into account all the requirements.

Here is the complete list of the requirements for our task:

- The backup command should have a long-term storage.

- It should be a way to call the command quickly.

- It should be a possibility to extend the command by new features.

- The command should be able to combine with other commands.

First, let’s evaluate our knowledge of Bash. They are not enough to meet all these requirements. All the mechanisms we know do not fit here. Can a Bash script help us? I propose to explore its features. Then we can check if it is suitable for our task.

Bash Script

Let’s create a Bash script that does our backup command. Here are the steps for doing that:

1. Open the source code editor and create a new file. If you have integrated Notepad++ into Bash, run the following command:

2. Copy the backup command into the file:

1 (bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 ~/photo &&

2 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

3 ! echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt) &&

4 (cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

5 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

6 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt)

- Save the file in the home directory with the

photo-backup.shname. - Close the editor.

Now you have the Bash script file. Call the Bash interpreter and pass the script name there in the first parameter. Here is an example of this command:

You have run your first script. Any script is a sequence of Bash commands. The file on the disk drive stores them. When Bash runs a script, it reads and executes the file commands one by one. Conditional and loop statements can change this order of execution.

It is inconvenient to call Bash interpreter explicitly when running the script. Instead, you can specify its relative or absolute path. This approach works if you do the following steps to prepare the script:

1. Allow any user to execute the script by the following command:

- Open the script in an editor.

- Add the following line at the beginning of the file:

#!/bin/bash

- Save the modified file.

- Close the editor.

Now you can run the script by its relative or absolute path. Do it in one of the following ways:

1 ./photo-backup.sh

2 ~/photo-backup.sh

Let’s consider our preparation steps for launching the script. The first thing that prevents it from running is permissions. When you create a new file, it gets the following permissions by default:

This line means that the owner and his group can read and modify the file. Everyone else can only read it. No one can execute the file.

The chmod utility changes the permissions of the specified file. If you call it with the +x option, the utility allows everyone to execute the file. It gets the following permissions in this case:

When you run the script, your shell tries to interpret its lines. You may switch your shell from Bash to another one. It can be the Csh for example. In this case, you cannot execute our script. It happens because Bash and Csh have different syntax. They use different language constructions for the same things. We wrote the script in the Bash language. Therefore, the Bash interpreter should execute it.

There is an option to specify the interpreter that should execute the script. To do that, add the shebang at the beginning of the script file. Shebang is a combination of the number sign and exclamation mark. It looks like this:

Add the absolute path to the interpreter after the shebang. It looks like this in our case:

#!/bin/bash

Now the Bash interpreter always executes the script. It happens even if you use another shell for typing commands.

The file utility prints the type of the specified file. If the script does not have the shebang, the utility defines it as a regular text file. Here is an example output:

If you add the shebang, the utility defines this file as the Bash script:

The Bash interpreter has the same path /bin/bash for most Linux systems. However, this path differs for some Unix systems (for example, FreeBSD). It can be a reason why your script does not work there. The following shebang solves this problem:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

Here we call the env utility. It searches the path of the Bash executable in the list of the PATH variable.

Commands Sequence

Listing 3-1 demonstrates the current version of our script.

1 #!/bin/bash

2 (bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 ~/photo &&

3 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

4 ! echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt) &&

5 (cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

6 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

7 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt)

The script contains one command, which is too long. This makes it hard to read and modify. You can split the command into two parts. Listing 3-2 shows how it looks like.

1 #!/bin/bash

2

3 bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 ~/photo &&

4 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

5 ! echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt

6

7 cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

8 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

9 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

Unfortunately, the behavior of the script has changed. Now the logical AND does not take place between the bsdtar and cp commands. Therefore, Bash always tries to copy files even if archiving has failed. This is wrong.

The script should stop if the bsdtar call fails. We can reach this behavior with the exit Bash built-in. It terminates the script when called. The command receives the exit code as the parameter. The script returns this code on termination.

Listing 3-3 shows the script with the exit call.

exit call1 #!/bin/bash

2

3 bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 ~/photo &&

4 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

5 (echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt ; exit 1)

6

7 cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

8 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

9 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

We changed the command that calls the bsdtar utility. It looked like this before:

It became like this after adding the exit call:

The “E” letter means the exit command here.

If bsdtar returns an error, Bash evaluates the RHS operand of the logical OR. It is equal to “(F1; E)”. We removed the negation of the echo command because its result is not necessary anymore. Bash calls exit after echo. We expect that this call terminates the script.

Unfortunately, the exit call does not terminate the script. It happens because parentheses create a child process. The child Bash process is called subshell. It executes the commands specified in parentheses. When they are done, Bash continues executing the parent process. The parent process is the one that spawned the subshell.

The exit call finishes the subshell in Listing 3-3. Bash calls the cp utility after that. To solve this problem, you should replace the parentheses with braces. Bash executes the commands in braces in the current process. The subshell is not spawned in this case.

Listing 3-4 shows the corrected version of the script.

exit call1 #!/bin/bash

2

3 bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 ~/photo &&

4 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

5 { echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt ; exit 1 ; }

6

7 cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

8 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

9 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

Notice the semicolon before the closing brace. It is mandatory here. Also, spaces after the opening brace and before the closing one are required.

Our problem has another solution. It is more elegant than calling the exit command. Suppose you want to terminate the script after the first failed command. The set Bash built-in can do that. It changes the parameters of the interpreter. Call the command with the -e option like this:

set -e

You can specify the same option when starting the Bash. Do it this way:

The -e option has several pitfalls. For example, it changes the behavior of the current Bash process only. The subshells it spawns work as usual.

Bash executes each command of a pipeline or logical operator in a separate subshell. Therefore, the -e option does not affect these commands. It means that the set command does not work well in our case.

Changing Parameters

Suppose you have moved your photos from the ~/photo directory to ~/Documents/Photo. If you want to support the new path in the backup script, you should change its code. Listing 3-5 shows how the new script looks like.

1 #!/bin/bash

2

3 bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 ~/Documents/Photo &&

4 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

5 { echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt ; exit 1 ; }

6

7 cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

8 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

9 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

Every time you move the photos from one directory to another, you have to change the script. It is inconvenient. A better solution would be to make a universal script that can handle any directory. Such a script should receive the path to photos as an input parameter.

When you run a Bash script, you can pass command-line parameters there. It works the same way as for any GNU utility. Specify the parameters separated by a space after the script name. Bash will pass them to the script. Here is an example:

This command runs our script with the ~/Documents/Photo input parameter. You can read it via the $1 variable in the script. If the script receives more parameters, read them via the variables $2, $3, $4, etc. These names match the numbers of the parameters. Variables of this type are called positional parameters.

There is a special positional parameter $0. It stores the path to the launched script. It equals ./photo-backup.sh in our example.

Let’s handle the input parameter in our script. Listing 3-6 shows how it looks like after the change.

1 #!/bin/bash

2

3 bsdtar -cjf ~/photo.tar.bz2 "$1" &&

4 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

5 { echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt ; exit 1 ; }

6

7 cp -f ~/photo.tar.bz2 /d &&

8 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

9 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

The $1 variable stores the path to the photos. We use it in the bsdtar call. There are double quotes around the variable name. They prevent the word splitting mechanism.

Suppose you want to archive photos from the ~/photo album path. Then you call the script this way:

"~/photo album"

Suppose that you skip quotes around the variable name when calling in the script. Then the bsdtar call looks like this:

&&

echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

{ echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt ; exit 1 ; }

In this case, the bsdtar utility receives the ~/photo album string in parts. It gets two parameters instead of one: ~/photo and album. These directories do not exist. Therefore, the script fails.

It is not enough to put parameters in quotes when calling a script. You should quote all occurrences of the corresponding variable name in the script. It happens because of the way how the Bash runs a program.

Suppose that you call a script from the shell. Then Bash spawns a child process to execute it. The child process does not receive quotes from the command line because Bash removes them. Therefore, you should add quotes again inside the script.

Now our backup script can handle the input parameter. What are the benefits of this solution? It provides you a universal script for making backups. The script can process any paths and types of input files: documents, photos, videos, source code, etc.

Adding the parameter processing to our script leads to one problem. Suppose you call it twice for making backups of photos and documents this way:

1 ./photo-backup.sh ~/photo

2 ./photo-backup.sh ~/Documents

The first command creates the ~/photo.tar.bz2 archive and copies it to the D disk. Then the second command does the same and overwrites the existing /d/photo.tar.bz2 file. This way, you lose the result of the first command.

To solve this problem, you should pick different names for the created archive. This way, you avoid filename conflicts. The simplest approach is to name the archive the same way as the target directory with the files to backup. Listing 3-7 shows how this solution looks like.

1 #!/bin/bash

2

3 bsdtar -cjf "$1".tar.bz2 "$1" &&

4 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

5 { echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt ; exit 1 ; }

6

7 cp -f "$1".tar.bz2 /d &&

8 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

9 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

Now the script picks a unique name for the archive. Call it this way, for example:

This command creates the ~/Documents.tar.bz2 archive and copies it to the D disk. In this case, the filename does not conflict with the photo archive called /d/photo.tar.bz2.

You can make one more improvement to the script. Call the mv utility instead of cp. It deletes the temporary archive in the home directory. Listing 3-8 shows the final version of the script.

1 #!/bin/bash

2

3 bsdtar -cjf "$1".tar.bz2 "$1" &&

4 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

5 { echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt ; exit 1 ; }

6

7 mv -f "$1".tar.bz2 /d &&

8 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

9 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

Now we get the universal backup script. Its old name photo-backup.sh does not fit anymore. The new version can copy any data. Let’s rename it to make-backup.sh.

Combination with Other Commands

At the moment, you can run our backup script by its absolute or relative path. If you integrate it into Bash, you can call it by the name. This is a convenient option when you use the script in pipelines or logical operators.

These are three ways to integrate some script into Bash:

- Add the script’s path to the

PATHvariable. Edit the~/.bash_profilefile for that. - Define the alias with an absolute path to the script. Do that in the

~/.bashrcfile. - Copy the script to the

/usr/local/bindirectory. ThePATHvariable contains this path by default. If there is no such directory in your MSYS2 environment, create it.

We have learned the first two ways when preparing your source code editor. The third way is very straightforward. You can do it on your own.

unalias make-backup.sh

Suppose that you have integrated the backup script with Bash in one of three ways. Then you can launch it by name like this:

You can combine the script with other commands using pipelines and logical operators. It works the same way as for any Bash built-in or GNU utility.

Here is an example. Suppose you need to backup all PDF documents of the ~/Documents directory. You can find them by the following find call:

"*.pdf"

Then you can apply our script to archive and copy each found file. Here is the command for that:

"*.pdf" -exec make-backup.sh {} \;

This command works well. It creates an archive of each PDF file and copies it to the D disk. However, this approach is inconvenient. It would be better to collect all PDF files into one archive. Let’s try the following command for that:

{} +

The command should pass all found files into the single make-backup.sh call. Unfortunately, it does not work as expected. It produces an archive with the first found PDF file only. Where are the rest of the documents? Let’s take a look at the bsdtar call inside the script. It looks like this:

"$1".tar.bz2 "$1"

The problem happens because we process the first positional parameter only. The $1 variables stores it. The bsdtar call ignores other parameters in variables $2, $3, etc. They contain the rest results of the find utility. This way, we cut off all results except the first one.

If you replace the $1 variable with $@, you solve the problem. Bash stores all script parameters in $@. The corrected bsdtar call looks like this:

"$1".tar.bz2 "$@"

The bsdtar utility now processes all script parameters. Note that the archive name still matches the first $1 parameter. It should be one word. Otherwise, bsdtar fails.

Listing 3-9 shows the corrected version of the backup script. It handles an arbitrary number of input parameters.

1 #!/bin/bash

2

3 bsdtar -cjf "$1".tar.bz2 "$@" &&

4 echo "bsdtar - OK" > results.txt ||

5 { echo "bsdtar - FAILS" > results.txt ; exit 1 ; }

6

7 mv -f "$1".tar.bz2 /d &&

8 echo "cp - OK" >> results.txt ||

9 ! echo "cp - FAILS" >> results.txt

Bash has an alternative variable for $@. It is called $*. If you put it in double quotes, Bash interprets its value as a single word. It interprets the $@ variable as a set of words in the same case.

Here is an example to explain the difference between the $@ and $* variables. Suppose you call the backup script this way:

"one two three"

In the script, Bash replaces the “$*” construct with the following word:

"one two three"

Here is the replacement for the “$@” construct:

"one" "two" "three"

Scripts Features

While solving the backup task, we considered the basic features of the Bash scripts. Let’s make a summary for them.

Here are the requirements for the backup task:

- The backup command should have a long-term storage.

- It should be a way to call the command quickly.

- It should be a possibility to extend the command by new features.

- The command should be able to combine with other commands.

The final version of the make-backup.sh script meets all these requirements. Here are the solutions for them:

- The hard disk stores the script file. It is long-term memory.

- The script is easy to integrate with Bash. Then you can call it quickly.

- The script is a sequence of commands. Each one starts on a new line. You can read and edit it easily. Thanks to parameterization, you can generalize the script for solving tasks of the same type.

- Due to integration with Bash, you can combine the script with other commands.

If your task requires any of these features, write a Bash script for that.

Variables and Parameters

We already met Bash variables several times in this book. You have learned the list of system paths in the PATH variable. Then you have used positional parameters in the backup script. It is time to get a good grasp on the topic.

Let’s start with the meaning of the “variable” term in programming. The variable is an area of memory where some value is stored. In most cases, this is short-term memory (RAM, CPU cache and registers).

The first generation of programming languages (for example, assembler) has minimal support of variables. When using such a language, you should refer to a variable by its address. If you want to read or write its value, you have to specify its memory address.

When working with memory addresses, you might get into trouble. Suppose you work on a computer with 32-bit processors. Then any memory address has a length of 4 bytes. It is the number from 0 to 4294967295. This number is twice larger for 64-bit processors. It is inconvenient to remember and operate with such big numbers. That is why modern programming languages allow you to replace a variable address with its name. A compiler or interpreter translates this name into a memory address automatically. These programs “remember” large numbers instead of you this way.

When should you apply variables? Our experience with PATH and positional parameters has shown that variables store some data. It is needed for one of the following purposes:

- Transfer information from one part of a program or system to another.

- Store the intermediate result of a calculation for later use.

- Save the current state of the program or system. This state may determine its future behavior.

- Set a constant value to be used repeatedly later.

A typical programming language has a special type of variable for each of these purposes. The Bash language follows this rule too.

Classification of variables

The Bash interpreter has two operation modes: interactive (shell) and non-interactive (scripting). Variables solve similar tasks in each mode. However, the contexts of these tasks are different. Therefore, there are more features to classify variables in Bash than in other languages.

Let’s simplify the terminology for convenience. It is not entirely correct, but it helps to avoid confusion. When we talk about scripts, we use the “variable” term. When we talk about shell and command-line arguments, we use the “parameter” term. These terms are often used synonymously.

There are four attributes for classifying variables in Bash. Table 3-1 explains them.

| Classification Attribute | Variable Types | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Declaration mechanism | User-defined variables | The user sets them. | filename="README.txt" ; echo "$filename" |

| Internal variables | The interpreter sets them. It needs them to work correctly. | echo "$PATH" |

|

| Special parameters | The interpreter sets them for the user. The user can read them but not write. | echo "$?" |

|

| Scope | Environment or global variables | They are available in any instance of the interpreter. The env utility lists them. |

echo "$PATH" |

| Local variables | They are available in a particular instance of the interpreter only. | filename="README.txt" ; echo "$filename" |

|

| Content type | String | It stores a string. | filename="README.txt" |

| Integer | It stores an integer. | declare -i number=10/2 ; echo "$number" |

|

| Indexed array | It stores a numbered list of lines. | cities=("London" "New York" "Berlin") ; echo "${cities[1]}" |

|

cities[0]="London" ; cities[1]="New York" ; cities[2]="Berlin" ; echo "${cities[1]}" |

|||

| Associative array | It is a data structure with elements that are key-value pairs. Each key and value are strings. | declare -A cities=( ["Alice"]="London" ["Bob"]="New York" ["Eve"]="Berlin" ) ; echo "${cities[Bob]}" |

|

| Changeability | Constants | The user cannot delete them. They store values that cannot be changed. | readonly CONSTANT="ABC" ; echo "$CONSTANT" |

declare -r CONSTANT="ABC" ; echo "$CONSTANT" |

|||

| Variables | The user can delete them. They store values that can be changed. | filename="README.txt" |

We will consider each type of variable in this section.

Declaration Mechanism

User-Defined Variables

The purpose of user-defined variables is obvious from their name. You declare them for your own purposes. Such variables usually store intermediate results of the script, its state and frequently used constants.

To declare the user-defined variable, specify its name, put an equal sign, and type its value.

Here is an example. Suppose that you want to declare a variable called filename. It stores the README.txt filename. The variable declaration looks like this:

filename="README.txt".

Spaces before and after the equal sign are not allowed. It works in other programming languages but not in Bash. For example, the following declaration causes an error:

filename = "README.txt"

Bash misinterprets this line. It assumes that you call the command with the filename name. Then you pass there two parameters: = and “README.txt”.

When declaring a variable, you can apply Latin letters, numbers and the underscore in its name. The name must not start with a number. Letter case is important. It means that filename and FILENAME are two different variables.

Suppose you have declared a variable filename. Then Bash allocates the memory area for that. It writes the README.txt string there. You can read this value back using the variable name. When you do that, Bash should understand your intention. If you put a dollar sign before the variable name, it would be a hint for Bash. Then it treats the word filename as the variable name.

When you reference the variable in a command or script, it looks like this:

$filename

Bash handles words with a dollar sign in a special way. When it encounters such a word, it runs the parameter expansion mechanism. The mechanism replaces all occurrences of a variable name by its value. Here is the example command:

$filename ~

The command looks like this after the parameter expansion:

Bash performs nine kinds of expansions before executing each command. They are done in a strict order. Please try to remember this order. If you miss it, you can get an error.

Here is an example of a mistake that happens because of expansions order. Suppose that you manipulate the “my file.txt” file in the script. For the sake of convenience, you put the filename into a variable. Its declaration looks like this:

filename="my file.txt"

Then you use the variable in the cp call. Here is the copying command:

$filename ~

Bash does word splitting after the parameter expansion. They are two different expansion mechanisms. When both of them are done, the cp call looks like this:

This command leads to the error. Bash passes two parameters to the cp utility: “my” and “file.txt”. These files do not exist.

Another error happens if the variable’s value contains a special character. For example, you declare and use the filename variable this way:

1 filename="*file.txt"

2 rm $filename

The rm utility deletes all files ending in file.txt. The globbing mechanism causes such behavior. It happens because Bash does globbing after the parameter expansion. Then it substitutes files of the current directory whose names match the “*file.txt” pattern. It leads to unexpected results. Here is an example of the rm call that you can get this way:

When referencing a variable, always apply double quotes. They prevent unwanted Bash expansions. The quotes solve problems of both our examples:

1 filename1="my file.txt"

2 cp "$filename1" ~

3

4 filename2="*file.txt"

5 rm "$filename2"

Thanks to the quotes, Bash inserts the variables’ values as they are:

1 cp "my file.txt" ~

2 rm "*file.txt"

We already know several Bash expansions. Table 3-2 gives the full picture. It shows the complete list of expansions and their order of execution.

| Order of Execution | Expansion | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brace Expansion | It generates a set of strings by the specified pattern with braces. | echo a{d,c,b}e |

| 2 | Tilde Expansion | Bash replaces the tilde by the value of the HOME variable. |

cd ~ |

| 3 | Parameter Expansion | Bash replaces parameters and variables by their values. | echo "$PATH" |

| 4 | Arithmetic Expansion | Bash replaces arithmetic expressions by their results. | echo $((4+3)) |

| 5 | Command Substitution | Bash replaces commands with their output. | echo $(< README.txt) |

| 6 | Process Substitution | Bash replaces commands with their output. Unlike Command Substitution, it is done asynchronously. The command’s input and output are bound to a temporary file. | diff <(sort file1.txt) <(sort file2.txt) |

| 7 | Word Splitting | Bash splits command-line arguments into words and passes them as separate parameters. | cp file1.txt file2.txt ~ |

| 8 | Filename Expansion (globbing) | Bash replaces patterns with filenames. | rm ~/delete/* |

| 9 | Quote Removal | Bash removes all unshielded characters , ' " that were not derived from one of the expansions. |

cp "my file.txt" ~ |

Let’s come back to the parameter expansion. When you put the dollar sign before a variable name, you use the short form of the expansion. Its full form looks this way:

${filename}

Use this form to avoid ambiguity. Ambiguity can happen when the text follows the variable name. Here is an example of such a case:

1 prefix="my"

2 name="file.txt"

3 cp "$prefix_$name" ~

Here Bash tries to find and insert the variable called “prefix_”. It happens because the interpreter appends the underscore to the variable name. You can solve this kind of problem if you apply the full form of the parameter expansion. Do it this way:

"${prefix}_${name}" ~

If you prefer to use the short form of the expansion, you have another option. Enclose each variable name in double quotes. Then Bash will not confuse them and nearby text. Here is an example:

"$prefix"_"$name" ~

The full form of the parameter expansion has several features. They help you to handle cases when a variable is undefined. For example, you can insert the specified value in this case. Here is an example:

"${directory:-~}"

Here Bash checks if the directory variable is defined and has a non-empty value. If it is, Bash performs a regular parameter expansion. Otherwise, it inserts the value that follows the minus character. It is the home directory path in our example.

Table 3-3 shows all variations of the parameter expansion.

| Variation | Description |

|---|---|

${parameter:-word} |

If the “parameter” variable is not declared or has an empty value, Bash inserts the specified “word” value instead. Otherwise, it inserts the variable’s value. |

${parameter:=word} |

If a variable is not declared or has an empty value, Bash assigns it the specified “word” value. Then it inserts this value. Otherwise, Bash inserts the variable’s value. You cannot override positional and special parameters this way. |

${parameter:?word} |

If the variable is not declared or has an empty value, Bash prints the specified “word” value in the error stream. Then, it terminates the script with a non-zero exit status. Otherwise, Bash inserts the variable’s value. |

${parameter:+word} |

If the variable is not declared or has an empty value, Bash skips the expansion. Otherwise, it inserts the specified “word” value. |

Internal Variables

You can declare variables for your own purposes. Bash also can do that. These variables are called internal or shell variables. You can change values for some of them.

Internal variables solve two tasks:

- They pass information from the shell to the applications it runs.

- They store the current state of the interpreter.

There are two groups of internal variables:

- Bourne Shell variables.

- Bash variables.

The first group came from Bourne Shell. Bash needs it for compatibility with the POSIX standard. Table 3-4 shows the frequently used variables of this group.

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

HOME |

The home directory of the current user. Bash uses this variable for tilde expansion and processing the cd call without parameters. |

IFS |

It contains a list of delimiter characters. The word splitting mechanism uses them to split the strings into words. The default delimiters are space, tab and a line break. |

PATH |

It contains the list of paths where Bash looks for utilities and programs. Colons separate the paths in the list. |

PS1 |

It is a command prompt. The prompt can include control characters. Bash replaces them with specific values (for example, the current user’s name). |

SHELLOPTS |

The list of shell options. They change the operating mode of the interpreter. Colons separate the options in the list. |

The second group of internal variables is Bash specific. Table 3-5 shows them. This list is incomplete. There are some more variables, but they are rarely used.

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

BASH |

The full path to the Bash executable file. This file corresponds to the current Bash process. |

BASHOPTS |

The list of Bash specific shell options. They change the operating mode of Bash. Colons separate the options in the list. |

BASH_VERSION |

The version of the running Bash interpreter. |

GROUPS |

The list of groups to which the current user belongs. |

HISTCMD |

The index of the current command in history. It shows you how many items are there. |

HISTFILE |

The path to the file that stores the command history. The default path is ~/.bash_history. |

HISTFILESIZE |

The maximum number of lines allowed in the command history. The default value is 500. |

HISTSIZE |

The maximum number of entries allowed in the command history. The default value is 500. |

HOSTNAME |

The computer name as a node of the network. Other hosts can reach your computer by this name. |

HOSTTYPE |

The string describing the hardware platform where Bash is running. |

LANG |

Locale settings for the user interface. They define the user’s language, region and special characters. Some settings are overridden by variables LC_ALL, LC_COLLATE, LC_CTYPE, LC_MESSAGES, LC_NUMERIC, LC_TYPE. |

MACHTYPE |

The string describing the system where Bash is running. It includes information from the HOSTTYPE and OSTYPE variables. |

OLDPWD |

The previous directory that the cd command has set. |

OSTYPE |

The string describing of the OS where Bash is running. |

POSIXLY_CORRECT |

If this variable is defined, Bash runs in the POSIX compatible mode. |

PWD |

The current directory that the cd command has set. |

RANDOM |

Each time you read this variable, Bash returns a random number between 0 and 32767. When you write the variable there, Bash assigns a new initializing number (seed) to the pseudorandom number generator. |

SECONDS |

The number of seconds elapsed since the current Bash process started. |

SHELL |

The path to the shell executable for the current user. Each user can use his own shell program. |

SHLVL |

The nesting level of the current Bash instance. This variable is incremented by one each time you start Bash from the shell or script. |

UID |

The ID number of the current user. |

The internal variables are divided into three groups depending on the allowed actions with them. These are the groups:

- Bash assigns a value to a variable at startup. It remains unchanged throughout the session. You can read it, but changing is prohibited. Examples:

BASHOPTS,GROUPS,SHELLOPTS,UID. - Bash assigns a default value to a variable at startup. Your actions or other events change this value. You can re-assign some values explicitly, but this can disrupt the interpreter. Examples:

HISTCMD,OLDPWD,PWD,SECONDS,SHLVL. - Bash assigns a default value to the variable at startup. You can change it. Examples:

HISTFILESIZE,HISTSIZE.

Special Parameters

Bash declares special parameters and assigns values to them. It handles them the same way as shell variables.

Special parameters pass information from the shell to the launched application and vice versa. A positional parameter is an example of this kind of Bash variable.

Table 3-6 shows frequently used special parameters.

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

$* |

The string with all positional parameters passed to the script. Parameters start with the $1 variable but not with $0. If you skip the double quotes ($*), Bash inserts each positional parameter as a separate word. With double quotes (“$*”), Bash handles it as one quoted string. The string contains all the parameters separated by the first character of the internal variable IFS. |

$@ |

The list of strings that contains all positional parameters passed to the script. Parameters start with the $1 variable. If you skip double quotes ($@), Bash handles each array’s element as an unquoted string. Word splitting happens in this case. With double quotes (“$@”), Bash handles each element as a quoted string without word splitting. |

$# |

The number of positional parameters passed to the script. |

$1, $2… |

They contain the value of the corresponding positional parameter. $1 matches the first parameter. $2 matches the second one, etc. These numbers are given in the decimal system. |

$? |

The exit status of the last executed command in the foreground mode. If you have executed a pipeline, the parameter stores the exit status of the last command in this pipeline. |

$- |

It contains options for the current interpreter instance. |

$$ |

The process ID of the current interpreter instance. If you read it in the subshell, Bash returns the PID of the parent process. |

$! |

The process ID of the last command launched in the background mode. |

$0 |

The name of the shell or script that is currently running. |

You cannot change special Bash parameters directly. For example, the following redeclaration of $1 does not work:

1="new value"

If you want to change positional parameters, use the set command. It redeclares all parameters at once. There is no option to change a single positional parameter only. Here is the general form of the set call:

set -- NEW_VALUE_OF_$1 NEW_VALUE_OF_$2 NEW_VALUE_OF_$3...

What to do if you need to change a single positional parameter? Here is an example. Suppose you call the script with four parameters like this:

You want to replace the third parameter arg3 with the new_arg3 value. The following set call does that:

set -- "${@:1:2}" "new_arg3" "${@:4}"

Let’s consider this command in detail. Bash replaces the first argument “$” with the first two elements of the $@ array. It leads that $1 and $2 parameters get their previous values. Then there is the new value for the parameter $3. Now it equals “new_arg3”. The “$” value comes at the end. Here Bash inserts all elements of the $@ array starting from $4. It means that all these parameters get their previous values.

All special parameters from Table 3-6 are available in the POSIX-compatible mode of Bash.

Scope

Environment Variables

Any software system has scopes that group variables. A scope is a part of a program or system where the variable name remains associated with its value. There you can convert the variable name into its address. Outside the scope, the same name can point to another variable.

A scope is called global if it spreads to the whole system. Here is an example. Suppose that the variable called filename is in the global scope. Then you can access it by its name from any part of the system.

Bash keeps all its internal variables in the global scope. They are called environment variables. It means that all internal variables are environment variables. You can declare your variable in the global scope too. Then it becomes a new environment variable.

Why does Bash store variables in the global scope? It happens because Unix has a special set of settings. They affect the behavior of the applications that you run. An example is locale settings. They dictate how each application should adapt its interface. Applications receive Unix settings through environment variables.

Suppose one process spawns a child process. The child process inherits all environment variables of the parent. This way, all utilities and applications launched from the shell inherit its environment variables. This mechanism allows all programs to receive global Unix settings.

The child process can change its environment variables. When it spawns another process, it inherits the changed variables. However, when the child changes its environment variables, it does not affect the corresponding variables of the parent process.

The export built-in command declares an environment variable. Here is an example of doing that:

export BROWSER_PATH="/opt/firefox/bin"

You can declare the variable and then add it to the global scope. Call the export command this way:

1 BROWSER_PATH="/opt/firefox/bin"

2 export BROWSER_PATH

Sometimes you need to declare the environment variables for the specific application only. List the variables and their values before the application call in this case. Here is an example:

MOZ_WEBRENDER=1 LANG="en_US.UTF-8" /opt/firefox/bin/firefox

This command launches the Firefox browser and passes it the MOZ_WEBRENDER and LANG variables. They can differ from the global Unix settings.

The last example works well in Bash. If you use another shell, you need another approach. Suppose that you use Bourne Shell. Then you can pass variables to the application using the env utility. Here is an example of doing that:

MOZ_WEBRENDER=1 LANG="en_US.UTF-8" /opt/firefox/bin/firefox

If you call the env utility without parameters, it prints all declared environment variables for the current interpreter process. Call it in your terminal this way:

The export Bash built-in and the env utility print the same thing when called without parameters. Use export instead of env. There are two reasons for that. First, the export sorts its output. Second, it adds double quotes to the values of all variables. They prevent you from making a mistake if some values have line breaks.

All names of environment variables contain uppercase letters only. Therefore, it is a good practice to name local variables in lower case. It prevents you from accidentally using one variable instead of another.

Local Variables

We have considered the user-defined variables. You can declare them in several ways. Depending on your choice, the new variable comes to the local scope or global scope (environment).

There are two ways to declare the global scope variable:

- Add the

exportcommand to the variable declaration. - Pass the variable to the program when launching it. You can do it with the

envutility when using a shell other than Bash.

If you do not apply any of these ways, your variable comes to the local scope. A variable of this kind is called a local variable. It is available in the current instance of the interpreter. A child process (except a subshell) does not inherit it.

Here is an example. Suppose that you declare the filename variable in the terminal window this way:

filename="README.txt"

Now you can print its value in the same terminal window. The following echo command does that:

echo "$filename"

The same echo command works well in a subshell. You can try it. Spawn the subshell by adding the parentheses around the Bash command. It looks like this:

(echo "$filename")

The child process does not get the local filename variable. Let’s check it. Start a child process by calling the Bash interpreter explicitly. Do it this way:

'echo "$filename"'

The -c parameter passes a command that the Bash child process executes. A similar Bash call occurs implicitly when you run a script from the shell.

We enclose the echo call in the single quotes when passing it to the bash command. The quotes disable all Bash expansions for the string inside. This behavior differs from the double quotes. They disable all expansions except the command substitution and parameter expansion. If we apply double quotes in our bash call, the parameter expansion happens. Then Bash inserts the variable’s value in the call. This way, we will get the following command:

"echo README.txt"

We are not interested in this command. Instead, we want to check how the child process reads the local variable. Therefore, the parent process should not insert its value into the bash call.

If you change a local variable in the subshell, its value stays the same in the parent process. The following commands confirm this rule:

1 filename="README.txt"

2 (filename="CHANGELOG.txt")

3 echo "$filename"

If you execute them, you get the “README.txt” output. It means that changing the local variable in the subshell does not affect the parent process.

When you declare a local variable, it comes to the shell’s variables list. The list includes all local and environment variables that are available in the current interpreter process. The set command prints this list when called without parameters. Here is an example of how to find the filename variable there:

set | grep filename=

The grep utility prints the following string with the filename value:

filename=README.txt

It means that the filename variable is in the list of shell variables.

Variable Content Type

Variable Types

It is common practice to use the static type system in compiled programming languages (such as C). When using this system, you decide how to store the variable in memory. You should specify the variable type when declaring it. Then the compiler allocates memory and picks one of the predefined formats to store this type of variable.

Here is an example of how the static type system works. Suppose you want to declare a variable called number. You should specify its type in the declaration. You choose the unsigned integer type, which has a size of two bytes. Then the compiler allocates exactly two bytes of memory for this variable.

When the application starts, you assign the 203 value to the variable. It is equal to 0xCB in hexadecimal. Then the variable looks this way in the memory:

00 CB

One byte is enough to store the 203 value. However, you forced the compiler to reserve two bytes for that. The unused byte stays zeroed. No one can use it in the scope of the number variable. If the variable has a global scope, the byte is reserved and unused while the application works.

Suppose that you have assigned the 14037 value to the variable. It is equal to 0x36D5 in hexadecimal. Then it looks like this in the memory:

36 D5

Now you want to store the 107981 (0x1A5CD) value in the variable. This number does not fit into two bytes. The variable’s size is defined in the declaration. The compiler cannot extend it automatically afterward. Therefore, it writes only part of the 107981 value into the variable. It looks like this in the memory:

The compiler discarded the first digit of the number. If you read the variable, you get 42445 (0xA5CD). It means that you lose the original 107981 value. You cannot recover it anymore. This problem is called integer overflow.

Here is another example of the static type system. Suppose you want to store the username in a variable called username. You declare this variable and assign it the string type. When doing that, you should specify the maximum length of the string. It can be ten characters, for example.

After declaring the variable, you write the “Alice” name there. If you use the C compiler, the string looks this way in memory:

41 6C 69 63 65 00 00 00 00 00

Six bytes are enough to store the string “Alice”. The first five bytes store characters. The last sixth byte stores the null character (00). It marks the end of the string. However, the compiler has reserved ten bytes for the variable. It fills the unused memory with zeros or random values.

Dynamic type system is an alternative to the static system. It uses another approach to choose how to store a variable in memory. This choice happens whenever you assign the new value to the variable. Together with the value, the variable gets new metadata. The metadata defines the variable type. They can change during the application work. Thus, the variable’s representation in memory changes too. Most interpreted programming languages use the dynamic type system (for example, Python).

Strictly speaking, Bash does not have the type system at all. It is not a language with a static or dynamic type system. Bash stores all scalar variables in memory as strings.

The scalar variable stores data of a primitive type. These data are the minimal building blocks to construct more complex composite types. The scalar variable is just a name for the memory address where its value is stored.

Here is an example of how Bash represents scalar variables in memory. Suppose you made the following variable declaration:

declare -i number=42

Bash stores the number variable in memory as the following string:

34 32 00

Any language with the type system needs one byte to store this integer. But Bash needs three bytes. The first two bytes store each character of the integer. The characters are 4 and 2. The third byte stores the null character.

The Bourne Shell language has the scalar variables only. Bash introduces two new composite types: indexed array and associative array.

The indexed array is a numbered set of strings. There each string corresponds to the sequence number. Bash stores such an array as a linked list in memory. A linked list is a data structure that consists of nodes. Each node contains data and the memory address of the next node. Node data are strings in this case.

The associative array is a more complicated thing. It is a set of elements. Each element consists of two strings. The first one is called “key”. The second is called “value”. When you want to access the array’s element, you should specify its key. It works the same as for the indexed array, where you specify the element’s index. The keys are unique. It means that the array cannot have two elements with the same keys. Bash stores associative array as a hash-table in memory.

Why are Bash “arrays” called arrays? Actually, they are linked lists and hash tables. A real array is the data structure whose elements are stored in memory one after another. Each element has a sequential number called an index or identifier. Bash “arrays” do not store their elements sequentially in memory. Thus, they are not arrays according to the definition.

Here is an example of how a real array stores its elements in memory. Suppose you have an array with numbers from five to nine. Each element takes one byte. Then the size of the array is five bytes. It looks this way in memory:

05 06 07 08 09

The indexing of arrays’ elements starts with zero. It means that the index of the first element equals 0. The second index equals 1 and so on. In our example, the first element with the 0 index equals integer 5. The second element equals 6. Elements follow each other in memory. Their indexes match the memory offset from the beginning of the array. Thus, the element with the third index has three bytes offset. Its value equals integer 8.

Let’s come back to the question about naming the Bash “arrays”. Only the authors of the language can answer it. However, we can guess. The name “array” gives you a hint of how to work with such a variable. When you have experience with another language, you know how to operate with a regular array. This way, you can start using Bash “arrays” immediately. You do not need to know how Bash stores these “arrays” internally.

Attributes

The Bash language does not have a type system. It stores all scalar variables in memory as strings. At the same time, Bash has arrays. They are composite types because an array is a combination of strings.

When you declare a variable in Bash, you should choose if it is scalar or composite. You make this choice by specifying metadata for the variable. Such metadata is called attributes. The attributes also define the constancy and scope of a variable.

The declare Bash built-in specifies the variable attributes. When you call it without parameters, declare prints all local and environment variables. The set command prints the same output.

The declare command has the -p option. The option adds variables attributes to the output data.

If you need information on a particular variable, pass its name to the declare command. Here is an example of the PATH variable:

declare -p PATH

The declare command also prints information about declared subroutines. They are called functions in Bash. A function is a program fragment or an independent block of code that performs a certain task.

Suppose you are interested in function declarations but not in variables. Then apply the -f option of the declare command. It filters out variables from the output. Here is the declare call in this case:

declare -f

You can specify the function name right after the -f option. Then the declare command prints information about it. Here is an example of the function quote:

declare -f quote

This command displays the declaration of the quote function. The function takes a string on the input and encloses it in single quotes. If the string already contains the single quotes, the function escapes them. You can call quote in the same way as any Bash built-in. Here is an example:

"this is a 'test' string"

The declare call without the -p option does not print a function declaration. It means that the following command outputs nothing:

declare quote

We have learned how to get information about already declared variables and functions using declare. Now let’s find out how this command sets attributes for new variables.

Table 3-7 shows the frequently used options of the declare command.

| Option | Definition |

|---|---|

-a |

The declared variable is an indexed array. |

-A |

The declared variable is an associative array. |

-g |

It declares a variable in the global scope of the script. The variable does not come to the environment. |

-i |

It declares an integer variable. When you assign it a value, Bash treats it as an arithmetic expression. |

-r |

It declares a constant. The constant cannot change its value after declaration. |

-x |

It declares an environment variable. |

Here are several examples of how to declare variables with attributes. First, let’s compare integer and string variables. Execute the following two commands in the terminal window:

1 declare -i sum=11+2

2 text=11+2

We declared two variables named sum and text. The sum variable has the integer attribute. Therefore, its value equals 13 that is the sum of 11 and 2. The text variable is equal to the “11+2” string.

Bash stores both variables as strings in memory. The -i option does not specify the variable’s type. Instead, it limits the allowed values of the variable.

Try to assign a string to the sum variable. You can do it in one of the following ways:

1 declare -i sum="test"

2 sum="test"

Each of these commands sets the sum value to zero. It happens because the variable has the integer attribute. Therefore, it cannot be equal to some string.

Suppose you have declared an integer variable. Then you do not need any Bash expansion for arithmetic operations on it. The following commands do correct calculations:

1 sum=sum+1 # 13 + 1 = 14

2 sum+=1 # 14 + 1 = 15

3 sum+=sum+1 # 15 + 15 + 1 = 31

Here the calculation results come after the hash symbol. Bash ignores everything after this symbol. Such lines are called comments.

Now execute the same commands with the string variable. You will get the following results:

1 text=text+1 # "text+1"

2 text+=1 # "text+1" + "1" = "text+11"

3 text+=text+1 # "text+11" + "text" + "1" = "text+11text+1"

Here Bash concatenates strings instead of doing arithmetic calculations. If you want to operate on integers instead, you should use the arithmetic expansion. Here is an example of this expansion:

1 text=11

2 text=$(($text + 2)) # 11 + 2 = 13

When you apply the -r option of the declare built-in, you get a constant. Such a call looks this way:

declare -r filename="README.txt"

Whenever you change or delete the value of the filename constant, Bash prints an error message. Therefore, both following commands fail:

1 filename="123.txt"

2 unset filename

The -x option of the declare command declares an environment variable. It provides the same result as if you apply the export built-in in the variable declaration. Thus, the following two commands are equivalent:

1 export BROWSER_PATH="/opt/firefox/bin"

2 declare -x BROWSER_PATH="/opt/firefox/bin"