Don’t just say ‘we can’t’

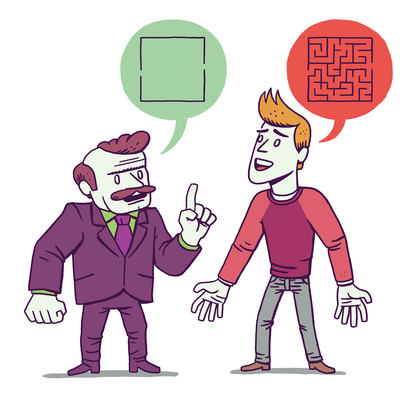

A statement of fact such as ‘we can’t do it’ tends to close down any further conversation. Often, this is not said deliberately to derail a process or meeting, rather the team or person has said it for one of two reasons:

- They are limited by their experience and knowledge.

- They might have made a judgement in their mind that the cost benefit analysis is not favourable.

In both cases, the outcome is verbalised as ‘we can’t’.

With infinite resources anything is possible. If we had access to the brightest minds in the world and enough time, we could achieve anything. Saying ‘we can’t’ and having unlimited resources are two extreme ends of the spectrum and things are not usually binary if we stop to consider them in more depth.

To exacerbate the problem, the other team members rarely argue against such a statement. This is because the person most likely to have an opinion on the feasibility of an idea is the most experienced one. Alternatively, the most dominant person in a team often makes such strong statements. In both cases, the others will be discouraged from challenging their judgement.

The outcome is that we just dismiss some solutions out of hand without discussing their underlying assumptions, and ultimately we miss out on potential improvements. So instead of just saying ‘we can’t’, spend some time exploring why. The results can be very revealing!

Explore the reasons for the initial reaction. Challenge the underlying, unspoken, assumptions. Quite often we find that teams unearth one or two of these underlying assumptions that they fundamentally disagree on. At this point, we have achieved a much more focused discussion.

Key benefits

Refusing to stop at ‘we can’t’ means we don’t prematurely rule potential improvements out due to false or unexplored assumptions and miss out on opportunities to explore improvement ideas.

Also significant is that asking ‘why’ helps the team to think of more possibilities and start to think more factually about what is involved in decision-making and what makes an idea a good investment of time (effort) and money. This will make them more capable of independent decision-making and problem-solving.

It also spreads knowledge across the team of the pros and cons of possible improvement ideas, bringing team alignment and hopefully autonomy.

Lastly we have applied collective reasoning: we have used the creativity and experience of the collective team to refine an improvement idea. This in itself improves the way the team functions.

How to make it work

Find some way of not allowing ‘we can’t’ to be a satisfactory final statement. A retrospective facilitator such as a scrum master can specifically look out for these ‘statements of fact’, but a better idea is to make it one of your team principles not to use the phrase ‘we can’t’.

It is quite often handy to ask these questions:

- If we had infinite time and money, would the response still be ‘we can’t’?

- Ask ‘based on what?’

- Repeatedly ask ‘why?’

As a start, imagine that you had infinite time and money – would the answer still be the same? We’ve found that posing the infinite resource question leads people to unravel the inbuilt assumptions about what makes the proposal difficult.

Another way to open up this dialogue is to ask ‘based on what?’ This question makes people analyse their thoughts, and hopefully challenge some of their own assumptions. Get team members to present their assumptions to the rest of the team, put them up on a board, prioritise them and then discuss whether they’re valid and what the cost of changing them might be.

A third useful question is ‘why’. Its use, increasingly popular in software delivery circles, is described by Taiichi Ohno in Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Toyota used a succession of ‘whys’ to drill down to the root cause when they were trying to solve problems. They found that five whys were probably sufficient to drive out the true root cause rather than the immediately obvious but possible superficial cause. We can apply a similar technique, one often used by children to annoy their parents when they tell them ‘no’. Keep asking ‘why’ until we flush out all the real reasons why people think that something is going to be difficult or impossible.

Funnily enough, it turns out that experts are human after all. They are constrained by their past experiences, not just the technology or domain, but also their past successes and failures. After exploring assumptions thoroughly, sometimes you hear something like ‘I don’t know, it’s just always been that way’, which is a red flag for a ‘please challenge me’ question. Remember, their reasons for rejecting something based on previous experience may no longer be valid, as technology and the tools are changing all the time.