5. HTTP Parameter Pollution

Description

HTTP Parameter Pollution, or HPP, refers to manipulating how a website treats parameters it receives during HTTP requests. The vulnerability occurs when parameters are injected and trusted by the vulnerable website, leading to unexpected behavior. This can happen on the back-end, server-side, where the servers of the site you’re visiting are processing information invisible to you, or on the client-side, where you can see the effect in your client, which is usually your browser.

Server-Side HPP

When you make a request to a website, the site’s servers process the request and return a response, like we covered in Chapter 1. In some cases, the servers won’t just return a web page, but will also run some code based on information given to it through the URL it’s sent. This code only runs on the servers, so it’s essentially invisible to you—you can see the information you send and the results you get back, but the process in between is a black box. In server-side HPP, you send the servers unexpected information in an attempt to make the server-side code return unexpected results. Because you can’t see how the server’s code functions, server-side HPP is dependent on you identifying potentially vulnerable parameters and experimenting with them.

A server-side example of HPP could happen if your bank initiated transfers through its website that were processed on its servers by accepting URL parameters. Say that you could transfer money by filling values in the three URL parameters from, to, and amount, which would specify the account number to transfer money from, the account to transfer to, and the amount to transfer, in that order. A URL with these parameters that transfers $5,000 from account number 12345 to account 67890 might look like:

https://www.bank.com/transfer?from=12345&to=67890&amount=5000

It’s possible the bank could make the assumption that they are only going to receive one from parameter. But what happens if you submit two, like the following:

https://www.bank.com/transfer?from=12345&to=67890&amount=5000&from=ABCDEF

This URL is initially structured the same as our first example, but appends an extra from parameter that specifies another sending account ABCDEF. As you may have guessed, if the application is vulnerable to HPP an attacker might be able to execute a transfer from an account they don’t own if the bank trusted the last from parameter it received. Instead of transferring $5,000 from account 12345 to 67890, the server-side code would use the second parameter and send money from account ABCDEF to 67890.

Both HPP server-side and client-side vulnerabilities depend on how the server behaves when receiving multiple parameters with the same name. For example, PHP/Apache use the last occurrence, Apache Tomcat uses the first occurrence, ASP/IIS use all occurrences, and so on. As a result, there is no single guaranteed process for handling multiple parameter submissions with the same name and finding HPP will take some experimentation to confirm how the site you’re testing works.

While our example so far uses parameters that are obvious, sometimes HPP vulnerabilities occur as a result of hidden, server-side behavior from code that isn’t directly visible to you. For example, let’s say our bank decided to revise the way it was processing transfers and changed its back-end code to not include a from parameter in the URL, but instead take an array that holds multiple values in it.

This time, our bank will take two parameters for the account to transfer to and the amount to transfer. The account to transfer from will just be a given. An example link might look like the following:

https://www.bank.com/transfer?to=67890&amount=5000

Normally the server-side code will be a mystery to us, but fortunately we stole their source code and know that their (overtly terrible for the sake of this example) server-side Ruby code looks like:

This code creates two functions, prepare_transfer and transfer_money. The prepare_transfer function takes an array called params which contains the to and amount parameters from the URL. The array would be [67890,5000] where the array values are sandwiched between brackets and each value is separated by a comma. The first line of the function adds the user account information that was defined earlier in the code to the end of the array so we end up with the array [67890,5000,12345] in params and then params is passed to transfer_money.

You’ll notice that unlike parameters, Ruby arrays don’t have names associated with their values, so the code is dependent on the array always containing each value in order where the account to transfer to is first, the amount to transfer to is next, and the account to transfer from follows the other two values. In transfer_money, this becomes evident as the function assigns each array value to a variable. Array locations are numbered starting from 0, so params[0] accesses the value at the first location in the array, which is 67890 in this case, and assigns it to the variable to. The other values are also assigned to variables in the next two lines and then the variable names are passed to the transfer function, which is not shown in this code snippet, but takes the values and actually transfers the money.

Ideally, the URL parameters would always be formatted in the way the code expects. However, an attacker could change the outcome of this logic by passing in a from value to the params, as with the following URL:

https://www.bank.com/transfer?to=67890&amount=5000&from=ABCDEF

In this case, the from parameter is also included in the params array passed to the prepare_transfer function, so the arrays values would be [67890,5000,ABCDEF] and adding the user account would actually result in [67890,5000,ABCDEF,12345]. As a result, in the transfer_money function called in prepare_transfer, the from variable would take the third parameter expecting the user.account value 12345, but would actually reference the attacker-passed value ABCDEF.

Client-Side HPP

On the other hand, HPP client-side vulnerabilities involve the ability to inject parameters into a URL, which are subsequently reflected back on the page to the user.

Luca Carettoni and Stefano di Paola, two researchers who presented on this vulnerability type in 2009, included an example of this behavior in their presentation using the theoretical URL http://host/page.php?par=123%26action=edit and the following server-side code:

<? $val=htmlspecialchars($_GET['par'],ENT_QUOTES); ?>

<a href="/page.php?action=view&par='.<?=$val?>.'">View Me!</a>

Here, the code generates a new URL based on the user-entered URL. The generated URL includes an action parameter and a par parameter, the second of which is determined by the user’s URL. In the theoretical URL, an attacker passes the value 123%26action=edit as the value for par in the URL. %26 is the URL encoded value for &, which means that when the URL is parsed, the %26 is interpreted as &. This adds an additional parameter to the generated href link without adding an explicit action parameter. Had they used 123&action=edit instead, this would have been interpreted as two separate parameters so par would equal 123 and the parameter action would equal edit. But since the site is only looking for and using the parameter par in its code to generate the new URL, the action parameter would be dropped. In order to work around this, the %26 is used so that action isn’t initially recognized as a separate parameter, so par’s value becomes 123%26action=edit.

Now, par (with the encoded & as %26) would be passed to the function htmlspecialchars. This function converts special characters, such as %26 to their HTML encoded values resulting in %26 becoming &. The converted value is then stored in $val. Then, a new link is generated by appending $val to the href value at. So the generated link becomes:

<a href="/page.php?action=view&par=123&action=edit">

In doing so, an attacker has managed to add the additional action=edit to the href URL, which could lead to a vulnerability depending on how the server handles receiving two action parameters.

Examples

1. HackerOne Social Sharing Buttons

Difficulty: Low

Url: https://hackerone.com/blog/introducing-signal-and-impact

Report Link: https://hackerone.com/reports/105953

Date Reported: December 18, 2015

Bounty Paid: $500

Description:

HackerOne blog posts include links to share content on popular social media sites like Twitter, Facebook, and so on. These links will create content for the user to post on social media that link back to the original blog post. The links to create the posts include parameters that redirect to the blog post link when another user clicks the shared post.

A vulnerability was discovered where a hacker could tack on another URL parameter when visiting a blog post, which would be reflected in the shared social media link, thereby resulting in the shared post linking to somewhere other than the intended blog. The example used in the vulnerability report involved visiting the URL:

https://hackerone.com/blog/introducing-signal

and then adding

&u=https://vk.com/durov

to the end of it. On the blog page, when a link to share on Facebook was rendered by HackerOne the link would become:

https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=https://hackerone.com/blog/introducing-signal?&u=https://vk.com/durov

If this maliciously updated link were clicked by HackerOne visitors trying to share content through the social media links, the last u parameter would be given precedence over the first and subsequently used in the Facebook post. This would lead to Facebook users clicking the link and being directed to https://vk.com/durov instead of HackerOne.

Additionally, when posting to Twitter, HackerOne included default Tweet text which would promote the post. This could also be manipulated by including &text= in the url:

https://hackerone.com/blog/introducing-signal?&u=https://vk.com/durov&text=another_site:https://vk.com/durov

Once a user clicked this link, they would get a Tweet popup which had the text another_site: https://vk.com/durov instead of text which promoted the HackerOne blog.

2. Twitter Unsubscribe Notifications

Difficulty: Low

Url: twitter.com

Report Link: blog.mert.ninja/twitter-hpp-vulnerability

Date Reported: August 23, 2015

Bounty Paid: $700

Description:

In August 2015, hacker Mert Tasci noticed an interesting URL when unsubscribing from receiving Twitter notifications:

https://twitter.com/i/u?iid=F6542&uid=1134885524&nid=22+26

(I’ve shortened this a bit for the book). Did you notice the parameter UID? This happens to be your Twitter account user ID. Noticing that, he did what I assume most of us hackers would do, he tried changing the UID to that of another user and…nothing. Twitter returned an error.

Determined to continue where others may have given up, Mert tried adding a second UID parameter so the URL looked like (again I shortened this):

https://twitter.com/i/u?iid=F6542&uid=2321301342&uid=1134885524&nid=22+26

And…SUCCESS! He managed to unsubscribe another user from their email notifications. Turns out, Twitter was vulnerable to HPP unsubscribing users.

3. Twitter Web Intents

Difficulty: Low

Url: twitter.com

Report Link: Parameter Tampering Attack on Twitter Web Intents

Date Reported: November 2015

Bounty Paid: Undisclosed

Description:

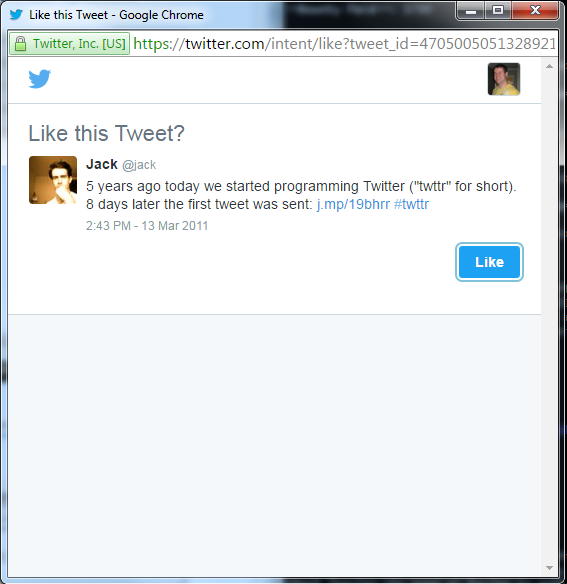

Twitter Web Intents provide pop-up flows for working with Twitter user’s tweets, replies, retweets, likes, and follows in the context of non-Twitter sites. They make it possible for users to interact with Twitter content without leaving the page or having to authorize a new app just for the interaction. Here’s an example of what one of these pop-ups looks like:

Testing this out, hacker Eric Rafaloff found that all four intent types, following a user, liking a tweet, retweeting, and tweeting, were vulnerable to HPP. Twitter would create each intent via a GET request with URL parameters like the following:

https://twitter.com/intent/intentType?paramter_name=paramterValue

This URL would include intentType and one or more parameter name/value pairs, for example a Twitter username and Tweet id. Twitter would use these parameters to create the pop-up intent to display the user to follow or tweet to like. Eric found that if he created a URL with two screen_name parameters for a follow intent, instead of the expected singular screen_name, like:

https://twitter.com/intent/follow?screen_name=twitter&screen_name=ericrtest3

Twitter would handle the request by giving precedence to the second screen_name value ericrtest3 over the first twitter value when generating a follow button, so a user attempting to follow the Twitter’s official account could be tricked into following Eric’s test account. Visiting the URL created by Eric would result in the following HTML form being generated by Twitter’s back-end code with the two screen_name parameters:

<form class="follow" id="follow_btn_form" action="/intent/follow?screen_name=ericrte\

st3" method="post">

<input type="hidden" name="authenticity_token" value="...">

<input type="hidden" name="screen_name" value="twitter">

<input type="hidden" name="profile_id" value="783214">

<button class="button" type="submit" >

<b></b><strong>Follow</strong>

</button>

</form>

Twitter would pull in the information from the first screen_name parameter, which is associated with the official Twitter account so that a victim would see the correct profile of the user they intended to follow, because the URL’s first screen_name parameter is used to populate the two input values. But, clicking the button, they’d end up following ericrtest3 because the action in the form tag would instead use the second screen_name parameter’s value in the action param of the form tag, passed to the original URL:

https://twitter.com/intent/follow?screen_name=twitter&screen_name=ericrtest3

Similarly, when presenting intents for liking, Eric found he could include a screen_name parameter despite it having no relevance to liking the tweet. For example, he could create the URL:

https://twitter.com/intent/like?tweet_id=6616252302978211845&screen_name=ericrtest3

A normal like intent would only need the tweet_id parameter, however, Eric injected the screen_name parameter to the end of the URL. Liking this tweet would result in a victim being presented with the correct owner profile to like the Tweet, but the follow button presented alongside the correct Tweet and the correct profile of the tweeter would be for the unrelated user ericrtest3.

Summary

The risk posed by HTTP Parameter Pollution is really dependent on the actions performed by a site’s back-end and where the polluted parameters are being used.

Discovering these types of vulnerabilities really depends on experimentation more so than other vulnerabilities because the back-end actions of a website may be a black box to a hacker, which means that, you’ll probably have very little insight into what actions a back-end server takes after receiving your input.

Through trial and error, you may be able to discover situations these types of vulnerabilities. Social media links are usually a good first step but remember to keep digging and think of HPP when you might be testing for parameter substitutions like UIDs.