Chapter 2. S3’s Architecture

A Quick, Tounge-in-cheek, Overview

Whenever I start explaining S3’s architecture to someone, part of me wants to affect a thick, drawling accent and say “Well, there’s these buckets, see, and, well, you put stuff in them.” That’s about all there is to it: no nesting, no directories, nothing but buckets and and the objects you put in them.

Before you decide to skip the rest of this chapter, remember that the devil is in the details (you might say that programming is quite devilish, as it is all about details). Keep reading to learn all about the little things that are going to trip you up as you delve deeper in to S3.

Amazon S3 and REST

What is REST?

Amazon S3 has two APIs: the SOAP API and the REST API. The SOAP API is basically ignored in this book. Why is that? Well, it’s partly a personal decision. I love playing with and building REST APIs. SOAP APIs I try my best to stay away from. Second, I firmly believe that REST is both simpler to understand and simpler to implement. Finally, we are all used to using RESTful web services, whether we know it or not. There’s this technology called the World Wide Web that is built on it.

So, what is REST? It stands for “Representational State Transfer”, and it was first described by Roy Fielding in his PhD. thesis ([http://www.ics.uci.edu/~fielding/pubs/dissertation/top.htm][1]). There’s no need to plow through the whole thesis. Here’s REST in a nutshell.

REST is a Resource Oriented Architecture (ROA). A Resource Oriented Architecture constrains the number of verbs you are using, but leaves the number of nouns that you are acting on with those verbs unlimited. A RESTful web service constricts the verbs you are using to five: GET, POST, PUT, DELETE and HEAD. Each resource will respond to some or all of the RESTful verbs.

Each verb has a specific task, as shown in the following table

Table 2.1. The RESTful Verbs

| Verb | Action | Idempotent? |

|---|---|---|

| GET | Responds with information about the resource | Yes |

| POST | Creates a sub-resource of the resource being POSTed to | No |

| PUT | Creates or updates the resource being PUT to | Yes |

| DELETE | DELETES the resource | Yes |

| HEAD | Gets metadata about the resource | Yes |

Amazon S3 And REST

Every object and bucket on S3 has a resource. You might think of it as the URL or path to the object or bucket. For example, an object with a key of claire.jpg that is stored in the bucket with a name of spattenphotos will have a resource of /spattenphotos/claire.jpg. The spattenphotos bucket has a resource of /spattenphotos.

To create a new object, you make a PUT to the object’s resource. The object’s value will be the body of the request. Making a PUT to /spattenphotos/scott.jpg will create a new object in the spattenphotos bucket with a key of scott.jpg. If I wanted to delete that object, I would make a DELETE request to /spattenphotos/scott.jpg. To see the contents of the object, I make a GET request to it. To see its meta-data without having to download the whole object, I make a HEAD request. Objects don’t respond to POST requests.

Buckets act in the same way: I create a new bucket by making a PUT request to its resource. I delete it with a DELETE request. I find its contents with a GET request. Buckets don’t respond to either HEAD or POST requests.

You might be thinking that this is pretty limited. What if I want to, for example, change the permissions on a bucket? That’s where sub-resources come in. Both buckets and objects have an acl sub-resource which contains information about the permissions on an object. The acl sub-resource is created by tacking ?acl on to the end of the bucket or object’s resource. So, the spattenphotos bucket has its acl sub-resource at spattenphotos?acl. (ACL stands for Access Control List. See “Understanding access control policies” for more information on them.) You set the permissions on a bucket or object by making a PUT request to its acl sub-resource. You read its permissions by making a GET request to the acl sub-resource.

Buckets have another sub-resource, logging, that responds to GET and PUT requests. Objects have a torrent sub-resource that responds only to GET requests.

Getting sort of repetitive, isn’t it? Yep, and that’s the whole point. There’s no need to memorize a whole list of methods for each resource. This makes the coding simpler. Here’s a table of all of the resources available in S3, and what the RESTful verbs do to them. Notice that none of the resources in S3 respond to POSTs. That’s okay: there’s nothing that says they should, and it makes things simpler.

Table 2.2. REST and S3

| Resource | how it is constructed | GET | PUT | DELETE | HEAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bucket | /<bucket_name> |

Lists the bucket’s | Creates or | Deletes | N/A |

| objects | updates the bucket | the bucket | |||

| Object | /<bucket_name>/ |

Gets the | Creates or | Deletes | Gets the |

<object_key> |

object’s | updates the object | the object | object’s | |

| content | metadata | ||||

| ACL | /<bucket_name>?acl |

Gets the ACL | Creates or | N/A | N/A |

| sub-resource | or | updates the ACL | |||

/<bucket_name>/ |

|||||

<object_key>?acl |

|||||

| logging | /<bucket_name>? |

Gets the | Turns off logging | N/A | N/A |

| sub-resource | logging |

logging status | for that bucket | ||

| for the bucket | |||||

| torrent | /<bucket_name>/ |

Gets the BitTorrent | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| sub-resource | <object_key>?torrent |

.torrent file |

|||

| for the object |

Keep this table in mind as you read through the rest of this chapter. It should help you to understand what’s going on a bit more easily.

For more reading about RESTful architecture, I highly recommend Leonard Richardson and Sam Ruby’s RESTful Web Services.

Buckets

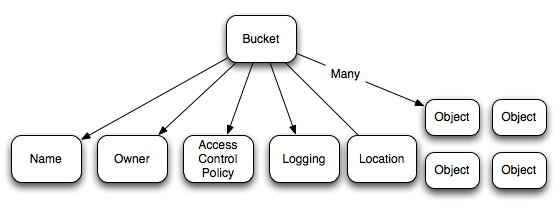

A bucket is a container for data objects. Besides the objects it contains, a bucket has a name, owner, Access Control Policy and a location.

Buckets cannot contain other buckets, so there is no nesting of buckets. Each AWS account can have up to 100 buckets. There is no limit on the number of objects that can be placed in a bucket.

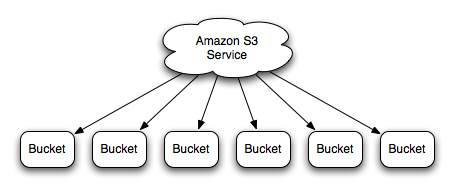

Figure 2.1. The Amazon S3 Service has many buckets

Figure 2.2. Each bucket has a name, an owner, an Access Control Policy, logging info, a location and many objects.

Bucket Names

When you create a bucket, you give it a name. Each bucket within S3 must have a unique name. If you try to create a bucket with a name that already exists, you will get a BucketAlreadyExists error. A bucket’s name cannot be changed after it is created. You can always, of course, make a new bucket and copy the contents of the old bucket in to it.

A bucket name must conform to a few rules. The following is lifted almost verbatim (with permission) from the Amazon S3 API documentation, currently found at http://docs.amazonwebservices.com/AmazonS3/2006-03-01/BucketRestrictions.html.

- Bucket names can only contain lowercase letters, numbers, periods (

.), underscores (_), and dashes (-). - Bucket names must start with a number or letter.

- Bucket names must be between 3 and 255 characters long.

- Bucket names cannot be in an IP address style (e.g.,

192.168.5.4).

As well, you will often want to use your bucket name as part of a URL, so here are a few other recommendations

- Bucket names should not contain underscores (

_). - Bucket names should be between 3 and 63 characters long.

- Bucket names should not end with a dash.

- Dashes cannot appear next to periods. For example, “my-.bucket.com” and “my.-bucket” are invalid.

- Bucket names should not contain upper-case characters.

Bucket URL

A bucket’s URL is given by

1 http://s3.amazonaws.com/<bucket_name>

Bucket Ownership

A bucket is owned by its creator, and that ownership cannot be transferred. You cannot create a bucket anonymously. If you want to give others access to a bucket that you own, then you need to edit the bucket’s access control policy.

Bucket Sub-resources

A bucket also has Access Control Policy and logging sub-resources.

The Access Control Policy sub-resource determines who can list or change items in the bucket. By default, only the owner of a bucket can view or change a bucket and its contents. You can change this by changing a bucket’s Access Control Policy (See “Access Control Policies”).

The logging sub-resource allows you to enable, disable and configure logging of requests made to a bucket. This is explained in “Enabling logging on a bucket”.

Creating and Deleting Buckets

You create a bucket by making a HTTP PUT request to the bucket’s URL. If you try to create a bucket that already exists and is owned by someone else, you will get a BucketAlreadyExists error. Re-creating a bucket that you own has no effect.

You delete a bucket by making a HTTP DELETE request to the bucket’s URL. A bucket cannot be deleted unless it is empty.

Listing a Bucket’s Contents

To list a bucket’s content, you make a HTTP GET request to the bucket’s URL. The response to your GET request will be an XML object telling you all of the bucket’s properties and listing all of the objects it contains. For more information, see “Listing All Objects in a Bucket”

A bucket can contain an unlimited number of objects. Listing the complete contents of a bucket can get unwieldy once the number of objects gets large. Also, Amazon will never return more than 1000 objects in a bucket listing. Luckily, there are a number of ways to filter the objects that are returned when you list a bucket’s contents. I won’t go in to detail here. Instead I will point to the recipes that explain how these methods are used.

Bucket filtering methods

max-keys- Sending this parameter in the query string will limit the number of objects returned in the bucket listing. By default,

max-keysis 1000. It can never be set to more than 1000.max-keyis used in conjunction withmarkerto paginate results. “Paginating the list of objects in a bucket” explains how to paginate the list of objects in a bucket. “Listing All Objects in a Bucket” explains how to make sure you get all of the objects in a bucket. prefix- If

prefixis set, only objects with keys that begin with that prefix will be listed (see “Listing only objects with keys starting with some prefix”).prefixis also used in conjunction withdelimiter(see below). marker- If

markeris set, only objects with keys that occur alpabetically aftermarkerwill be returned. This is used in conjunctions withmax-keysto paginate results in “Paginating the list of objects in a bucket”. delimiter- A

delimiteris always used in conjunction withprefix. It is used to help you move around in directory structures within your bucket. It’s use is best explained by example, so go check out “Listing objects in folders”.

S3 Objects

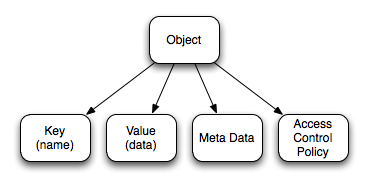

An S3 Bucket is just a container for S3 Objects. In many ways, an S3 Object is just a container for data. Amazon S3 has no knowledge of the contents of your objects. It just stores it as a bunch of bits. There are a few other attributes to an S3 Object, though.

Every S3 Object must belong to a bucket. It also has a key, owner, value, meta-data and an Access Control Policy.

Object Keys

An object’s key is its name. The name cannot be changed after it has been created and must be unique within a bucket. An Object’s key can be any sequence of between 0 and 1024 Unicode UTF-8 characters. This means that you can have a key with a name of length zero (the empty string, "").

Object Values

The value is the data that an object contains. The value is a sequence of bytes; Amazon S3 doesn’t really care what it is. The only limitation is that it must be less than 5 GB in size.

Object Metadata

An object can have two types of metadata: metadata supplied by S3 (system metadata), and metadata supplied by the user (user metadata). The metadata supplied by Amazon S3 are (at the time of writing) the following:

- Last-Modified

- The date and time the object was last modified

- ETag

- An MD5 Hash of the Object’s value. You can use this to determine if the Object’s value is the same as another chunk of data that you have access to. This is discussed in more detail in “Synchronizing a Directory”

- Content-Type

- The object’s MIME type. If you don’t provide a content type, it defaults to

binary/octet-stream(see http://docs.amazonwebservices.com/AmazonS3/2006-03-01/RESTObjectPUT.html). - Content-Length

- The length of the Object’s value, in bytes. This length does not include the key or the metadata.

You can also add your own, custom metadata to an object. For example, if you are storing a photograph on S3, you might want to store the date the photo was taken and the names of the people in the picture. See “Reading an object’s metadata” and “Adding metadata to an object” to learn how to set and read an Object’s user metadata.

Bit Torrents

Any object that is publicly readable may also be downloaded using a BitTorrent client. “Seeding a bit torrent” explains how this is done.

Access Control Policies

Both buckets and objects have Access Control Policies (ACP). An Access Control Policy defines who can do what to a given Bucket or Object. ACPs are built from a list of grants on that object or bucket. Each grant gives a specific user or group of users (the grantee) a permission on that bucket or object. Grants can only give access. An object or bucket without any grants on it is un-readable or writable. “Understanding access control policies” will get you started by explaining how ACLs work. After that, you might want to read about “Reading a bucket or object’s ACL”, “Granting public read access to a bucket or object using S3SH” or “Giving another user access to an object or bucket using S3SH”.

Logging Object Access

If you want to get some analytics on who is using the objects in one of your buckets, you can turn on logging for that bucket. “Determining logging status for a bucket” explains how to find out if logging is enabled for a bucket, and, if it is, what the logging settings are. “Enabling logging on a bucket” shows you how to turn logging on for a bucket, how to set what bucket the logs are sent to and how to prepare the bucket that is receiving the logs. “Allowing someone else to read logs in one of your buckets” shows you how to give someone else read access to your logs. “Logging multiple buckets to a single bucket” shows you how to collect all of your buckets’ logs into a single logging bucket, and how to set a prefix so you can tell which bucket the logs came from. “Parsing logs” and “Parsing log files to find out how many times an object has been accessed” discuss parsing logs and extracting data from them. Finally, if you don’t want to do any of this yourself, “Accessing your logs using S3stat” shows you how to use s3stat.com to parse your logs for you.