Chapter 1: Introducing databases and PostgreSQL

How databases fit in

Imagine that you work in a small direct-response mail order company that takes orders from customers by phone. Each agent in the call center downstairs has a stack of paper order forms on his desk, and when he receives an order he writes down the product name(s), quantity ordered, and the customer’s address and payment information. He uses a calculator or computer to sum up the order total, and tells the customer how much they’ll be charged.

Periodically, a data entry worker visits the call center and picks up stacks of filled-in order forms. She enters each order’s details into a file on her desktop computer, perhaps a big Excel spreadsheet that she’s designed herself for this task. At the end of the day, when all the orders are entered, she sends the complete file to two other departments: fulfillment, which processes the customer’s credit card and packs and ships the orders, and accounting, which calculates each salesperson’s commission.

This is the kind of process that a small business might develop when it’s first getting started, and in fact, it’s exactly the process that I encountered when I was first learning about databases at a small company in Maine. Unfortunately, simple processes like this tend to get complicated as the company gets bigger, and can become impossible to maintain. Just a few of the challenges this company might face are:

- When the business grows to the point that multiple data entry workers are needed, they must coordinate their work somehow. Perhaps each worker creates her own file, and they must combine them at the end of the day. There are many opportunities for errors to enter the system.

- If a payment is declined, or if a customer returns an order, one of the old spreadsheets must be updated, but which one? The data is kept in the order it was entered, not alphabetized by customer, and if there are now multiple spreadsheets for each day of business, searching for the old order is a big challenge.

- As a result of the update made by fulfillment or customer service, multiple versions of the data exist. Accounting still has the old data, and they need to be notified of the change so they can correct the salesperson’s commission. Even if they’re sent the modified file, how do they know which row(s) are changed? And as more changes are made over time, who is responsible for keeping the official record?

- As the business grows, the order entry data may change. For example, product numbers or names may change, discounts or coupon codes may be introduced, or some kind of membership number may be offered to frequent customers. As the paper order forms change, the spreadsheets must also be modified. Consequently, today’s data files look different from last month’s and even more different from last year’s. As people change jobs and leave the company, can their replacements even read the older data?

As this small business becomes a medium-sized enterprise, the seeming convenience of using a spreadsheet can become a nightmare of data management. Before long, the data entry workers, accountants, and other departments may find they spend more time managing spreadsheets than doing their main jobs. And sooner or later, management may wish to use the historical order data for a new purpose, such as customer relationship management (CRM) or business intelligence (BI). What they’ll find is that the data is spread out over a huge number of files, with multiple versions of each file existing in different places, and older files having a different structure and meaning from newer files. What a mess!

A database

Imagine instead if there was a black box in the office into which all those order forms were fed. At any time, a person could ask the black box to retrieve any order record (or list of records) by time and date, by customer name, by product, or another attribute. Fulfillment could ask for the payments waiting to be processed, and it would get a printout of exactly that. Shipping could request invoices and mailing labels for orders ready to ship. Accounting could ask for the sum of order totals taken by each salesperson for a given time period. Moreover, changes could be filed in the black box and all subsequent requests would include the up-to-date, corrected information. The black box serves as the manager of, and the official system of record for, all the company’s order data.

That’s the big idea of a database. Instead of having every person or department or program keep its own copy of the data, a database serves as a system of record, a “single source of truth” that can always be accessed by everyone who needs it for their different purposes. A database stores some knowledge about the data’s structure and meaning, or metadata, so diverse users can know what they’re looking at. And most importantly, a database offers flexible but easy-to-use query methods so that users can request just the data they want, whether it’s a single record, a collection of data, or an aggregation into averages, counts, or sums.

A variety of databases

Databases come in many shapes and sizes and they serve a lot of different purposes. Most often, a database acts as a server, that is, a software program that is always on, waiting for requests and responding to them. It’s necessary for databases to always be on and available if people and other software systems are going to depend on them to store data. (Otherwise, those people and programs will have to store their own data locally, which defeats the purpose of a database – independent and shared data management.)

A database administrator (DBA) is therefore responsible for a key component of a business’s IT infrastructure. If the database goes down, a lot of other programs go down, so the DBA ought to learn best practices for managing security, keeping backups and recovering from disasters. Maintaining and upgrading a database has been compared to maintaining a sailing ship when it is out to sea. The DBA can’t just take the database out of service to work on it however he wants; the business must stay afloat.

Server-based databases vary widely in scale and scope. Some databases support a single application, such as a dynamic website, and these may run on the same physical computer as the application’s code. A larger database might run on a dedicated machine that multiple users access over the network; for example, a company may keep a database of customer relationship information which can be accessed by sales, marketing, and customer service systems.

Larger still are enterprise-scale databases that integrate a wide variety of subject areas. This category includes enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems that integrate several areas of business operations, and enterprise data warehouses (EDW) used for analysis and reporting of business performance. Enterprise-scale databases may run on mainframes or may be distributed over large clusters of dozens or hundreds of computers.

What you’ll learn from this book

This book will introduce you to relational databases, with data modeling and the SQL language first and foremost. It covers the scope of a typical first database course in an information systems or analytics program at the university level. It can be used as a textbook for an instructor-led course—instructors, please contact the author for an instructor’s guide, slides and materials—or used for self-guided study with or without the video lectures produced by the author (coming soon on Youtube and Leanpub).

My main goal in creating this book is to make data modeling and SQL understandable to the reader, so it may serve as a good low-cost supplement for students who are struggling with a theory-heavy textbook and having a hard time getting the point. Instead of starting with loads of theory up-front, I’ll take a more pragmatic approach based on relational data modeling “patterns” and examples.

This book will also provide a lot of practice using SQL, the structured query language common to all relational databases, because the most frequent feedback I’ve heard from my undergraduate students (and from companies that hire them) is that they need more practice with SQL.

The database of choice for this book is PostgreSQL (often nicknamed “Postgres”), an open-source database that has become quite popular with developers in recent years. Compared to some other popular databases like SQL Server and MySQL, there aren’t many good books about Postgres, so I hope this book will be valuable if only for its examples. Postgres makes a good choice for teaching because it is free software (both “free as in free speech” and “free as in free beer”), and because it runs on all the major platforms—Windows, Mac OS, and Linux—so you can follow this book no matter what kind of computer you have handy.

Rest assured that the lessons of this book are transferable to other relational databases. Each of the major brands has its own quirks and special features, but this book mainly covers the fundamentals that apply everywhere. As currently planned, one chapter (Chapter 7) will exhibit some of PostgreSQL’s distinctive features and capabilities.

Lab 1: your first PostgreSQL database

Up and running with Postgres

PostgreSQL is available for free at www.postgresql.org and is extremely well documented there. Installation instructions will vary depending on your platform, and should be pretty straightforward. You can probably accept all the default configuration options. Be sure to remember the password you set during installation. You’re up and running when you can enter the command psql at your system’s command line to log in to the local PostgreSQL server. You will recognize this by a readout of the psql version number, a statement about how to get help, and a change to the command prompt. At the time of this writing, it looks like this for me (on my Mac):

To quit psql, enter \q at the prompt. If the above doesn’t make any sense to you, don’t worry. Appendix A to this book includes my own tested instructions for installing Postgres on Windows, Mac, and Linux. You can also refer to the online documentation. Come back to this page when you’re up and running.

Relations are tables

Databases can be classified according to the types of abstractions they allow you to model your data with. In a relational database, data is modeled as a set of tables with structured rows and columns. Other data models are possible. In a document-oriented database such as MongoDB, data is modeled as documents with tree-like structures. In a graph database like Neo4J, data is structured as a network (a mathematical graph) with nodes and edges. Compared to those newer forms, the relational model is far more commonly seen and better understood, and is the most versatile. Relational databases have been tried and tested in business for nearly four decades, and are probably the best tool for the job in all but a few specialized cases.

The tables you find in a relational database are properly called relations. A relation is not just any table; it is a construct derived from set theory and adheres to the following constraints:

- Every row has the same columns.

- Column names must all be different.

- Each column is defined to contain just one specific type of data.

- Each row must be unique; usually we enforce this by adding a machine-generated ID number to each row, known as the primary key column.

- No inherent ordering of rows or columns, or other information about how to display the data, is stored in the table.

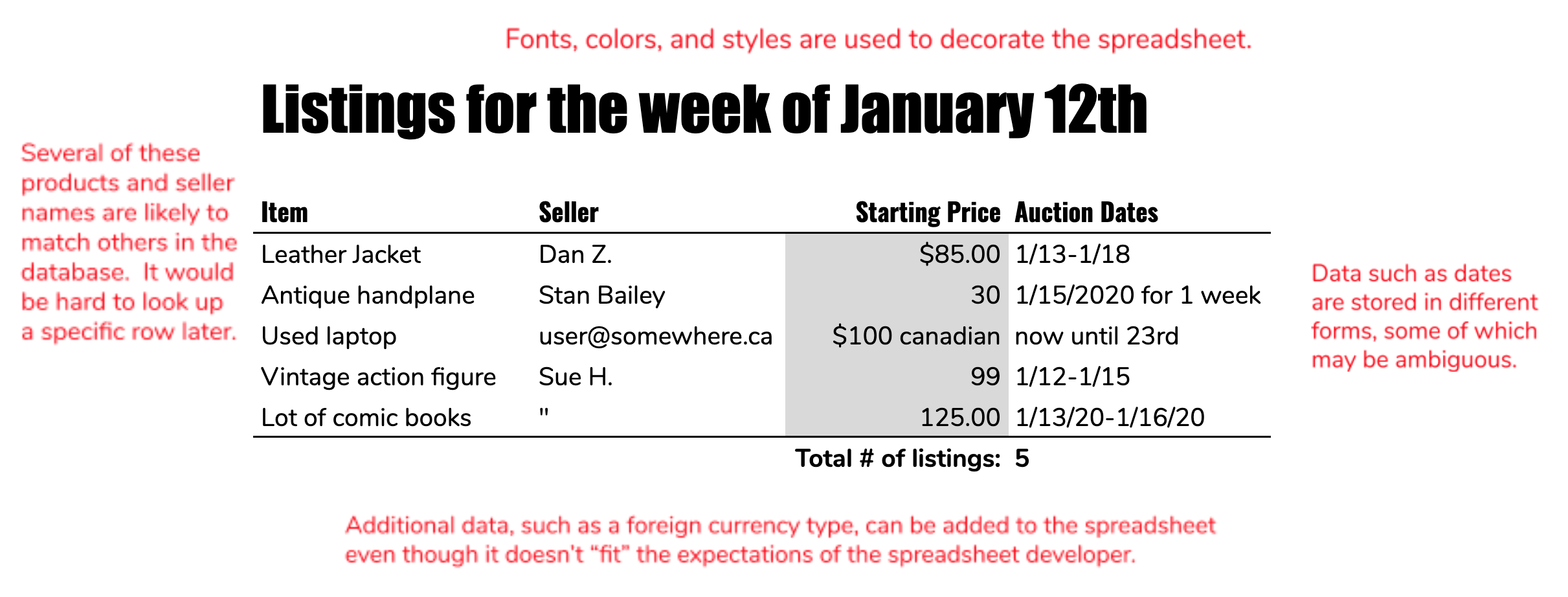

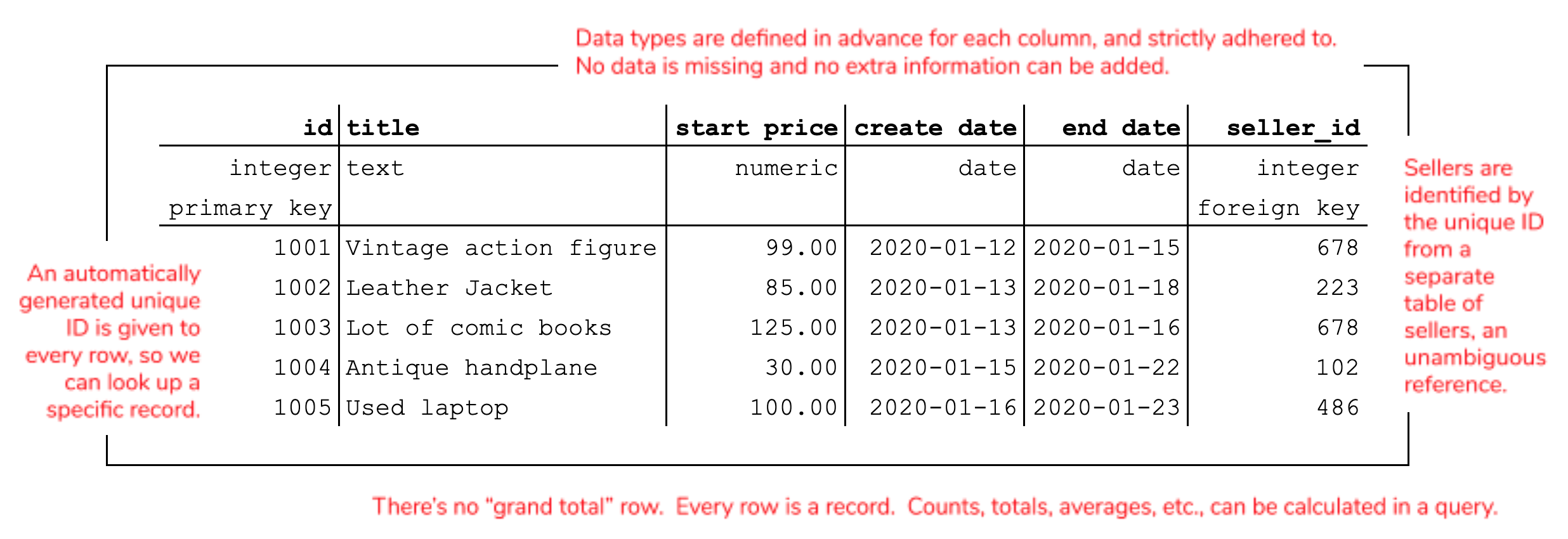

Consequently, a relation is a simpler and less flexible structure than a table you might create in a spreadsheet program like Microsoft Excel. Spreadsheets allow you to mix data types, to have rows with different numbers of columns, and to decorate your data with display logic like fonts, colors, and sizing. Figures 1-1 and 1-2 illustrate the comparison with an example of some listings data from an online auction site..

In a spreadsheet the user can be lax in data entry, for example listing a date as “today”, or entering a quotation mark (meaning “ditto”) instead of spelling something out. Data types unanticipated at the time the table was designed could be inserted freely; for example, a price in Canadian dollars might be given in a column that normally doesn’t specify currency type. Although these are convenient for data entry, they may lead to problems for computer systems that want to use the data (for example, accounting systems). The spreadsheet user can also decorate the data with fonts, styles, sizes and colors in order to make it more readable, and he can add extra information like a “grand total” row.

As seen in Figure 1-2, a database table (or relation) is much more strictly defined. Data types must be specified in advance for each column, guaranteeing uniformity. That means special cases must be anticipated before they occur. In this example, the database designer specified that a listing must have both start and end dates specified, to prevent any ambiguity, and that the price must be strictly numeric. In order to guarantee that each row is unique, and therefore can be looked up, the database user has added a primary key column and populated it with an auto-generated ID number. One use of such a key is as a “foreign key” – our listings table references a seller in another table by that table’s unique primary key column.

No other information is found in the rows of a relation except the data itself: not fonts and styles, and not even the sort order. Totals, averages, and the like wouldn’t be stored in the table either, because rows correspond only to individual data “records”. Aggregated values like totals and averages could be calculated in a query or perhaps stored in additional tables created specifically for the purpose.

Creating a PostgreSQL database

Let’s fire up PostgreSQL and create a table. (I probably won’t use the word “relation” much after this, except for a bit of theory in Chapter 2. Where I write “table”, you should be able to figure out what I mean.)

First, a note about the term “database”. As I have described it above, a database is a system that organizes and stores data and, importantly, makes it available to people who need to search or retrieve it. Others more precise than I will distinguish between the database, which is the organized data store, and the database management system (DBMS) which is a program like PostgreSQL that creates the data store and grants us access to it. When we call Postgres (or Oracle, or SQL Server, etc.) a database, we are using the term more generally to include both the data store and the DBMS, since they go together.

To understand how we interact with PostgreSQL, though, you need a third definition of the term. In PostgreSQL, a database is a logical subdivision of the data store. You may create any number of tables grouped into databases on the same server. (For the purposes of this book’s labs, your personal computer is acting as a PostgreSQL server.) Table names must be unique within a database, but not within a server. If several examples in this book include a table called “customers”, you can avoid a conflict by creating a new database for each lab.

What we’ll do in this first lab, then, is:

- Create a PostgreSQL database called “auctagon”

- Log in to that database with

psql - Create a table of Purchases

- Query the single-table database with SQL

Database creation

You can create a database from your operating system’s command line (i.e., before logging in to PostgreSQL with psql or another front-end tool), by using the command createdb. The basic structure of this command is createdb [OPTIONS] [DBNAME], and you can learn more by typing createdb --help at the command prompt. Thus, the following command creates a database called “auctagon”:

If necessary, you can also drop (i.e., delete) the new database from the commmand line, with:

For future reference, you can also create and delete databases using SQL once you’re logged in to psql: the CREATE DATABASE and DROP DATABASE commands, respectively. One way or another, create that database, which will be home to your first table.

Introducing psql

The command-line client for PostgreSQL is psql, and you launch it by entering psql on the command line. This will not open a new window, but rather you will see a brief welcome and the command prompt will be different from the operating system’s default prompt.

The change in the command prompt means you’re in a different environment. Here, you can enter SQL queries or some commands specific to psql. The first thing I’d recommend you do is type help, which introduces you to a few of the latter. Most psql commands begin with a backslash (\) and you can get a full listing of them by entering the command \?. If you need to quit, \q is the command for that. If you want to, take some time now to explore the lists of SQL queries and psql commands possible.

By default, when you start psql you’re connecting to the database with the same name as your PostgreSQL username. If you installed Postgres using Docker, or used an installer on Windows, that will probably be “postgres”. If you installed it on a Mac or Linux machine, the default database may have the same name as your computer login name. Any SQL commands you enter at the prompt will be executed on the default database’s tables, and that isn’t what we want. To switch over to the new database you created, use the \c command:

Notice that the prompt changes to tell you which database you’re working in.

Creating a table

To create a table in the “auctagon” database, we use the aptly-named SQL CREATE TABLE command. I will expand on its usage in Chapter 2, but the basic form of it is as follows:

As I mentioned, one of the special characteristics of a relation is that each column allows data only of a specified type. PostgreSQL offers a number of built-in data types, such as numeric, text, date, and more. I will discuss the choice of data type more in Chapters 2 and 8, but it need not delay an introductory example. There are many optional clauses available in the CREATE TABLE statement which can be discussed later or looked up in the documentation; the only one we need now is PRIMARY KEY, a flag which indicates that a particular column is going to contain unique values that may be used to look up specific rows later.

The command to create our table of Listings is as follows. You may type this in at the psql prompt, even if it spans several lines. The code won’t execute until the semicolon (;) is reached. Mind the cases: in PostgreSQL the SQL keywords (i.e. CREATE TABLE, PRIMARY KEY, and the data types) may be uppercase or lowercase, but you should only use lower case letters and underscores (_) for the table and column names. PostgreSQL isn’t very sensitive to whitespace, so you can enter this code all on one line, or spread out over several lines, with indentation and tabs if you want them.

If the command succeeded, you’ll see “CREATE TABLE” in the output. If there’s an error message instead, don’t worry, just try again. The most likely causes of errors are typos in the data types, the wrong number of commas, and uppercase letters in the table or column names. If the command worked but you defined the table incorrectly, the easiest solution is to start over by issuing the command DROP TABLE purchases; and creating the table anew.

You can confirm that the table exists with the psql command \dt, which displays a table of all the tables in the currently selected database:

That’s all there is to defining a table, at least an empty one. In order for us to demonstrate some SQL queries, though, we’ll need to store some data in the table with the SQL INSERT command. We’ll use the simplest form of this command, adding only one row at a time to the table, for example:

Take note that text data must be wrapped in quotation marks ('), and numbers must not.

Writing INSERT commands by hand will quickly become tiresome, and is not the usual mode of entering data into a real database. Typically the database will support software (such as a web app, or an enterprise system) that generates data insertion and update commands automatically. Another way we might load a lot of data quickly is to read in a file containing (presumably machine-generated) INSERT commands. In psql you can execute SQL commands from a file using the \i command.

I have provided a script file containing 300 lines of purchase data on the GitHub repository that supports this book. You may find the file AUCTagon1.sql at https://github.com/joeclark-phd/databasebook-postgres, in the “psql_scripts” folder. If I have downloaded this file to a Windows laptop and saved it in the directory C:/psql_scripts, the command looks like this:

Be sure to use the correct file path for your operating system and the location where you downloaded the script.

Regardless of how you insert data into the table, please add at least several records so that you can try some meaningful queries in the next section. If you are experiencing errors with INSERT commands, check that the number of values you’re inserting matches the number of columns in the table, that they’re in the right order, and that the order_id number is unique for each inserted row. If you run into problems, you can empty the table by entering the command DELETE FROM purchases; and start again.

Querying your data with SQL

SQL is the structured query language more or less common to all relational databases, and it really shines for its ability to extract just the data you want from a table or group of tables. What kinds of queries might you want to make of this data? You might want specific subsets of the data, such as all the orders for a particular product or in a particular state. Or you might want to aggregate the data, that is, sum or count or average them, perhaps in groups. Even with one simple table, there are quite a few ways to query it.

Let’s start with the basics. Your first query is the simplest: it just requests all the data.

That’s quite a lot of rows, so I’ll give you a trick to shorten the results. Affix “LIMIT <number>” to the end of the query to get only the first several rows:

The meaning of the “*” is “all columns”. It’s possible to request only certain columns, for example, let’s say you only want to know the title and starting price of each auction listing. Specify the desired columns in the “SELECT” clause:

An optional addition to the query is the “ORDER BY” clause, which (as you might guess) determines the sort order of the results. Since we are limiting the results to only 10 rows, this query would give you the ten lowest-priced auctions:

Most of the time you don’t want every row, but want to select a subset of the data. This is accomplished with the “WHERE” clause, certainly one of the most important clauses in a query. You may request a single row by its primary key, for example:

Or you may give criteria that qualify more than one row, if you want to see a specific subset. For example:

The criteria don’t have to be “equality” conditions, by the way. We can also use numerical inequalities; any row for which the inequality is “true” will be returned:

You can stitch together multiple conditions with “AND” and “OR” to make a more complex query. For example, if you want to find all auctions ending within a particular date range, you can use something like this:

Another condition you might use, for a primitive text search, is “LIKE”. The “%” character is a wildcard that matches any text. Thus, the following code returns all auctions that end with “Handplane”:

Substitute “ILIKE” for a case-insensitive match.

Aggregate queries

The queries above allow you to carve out subsets of the data by requesting only certain columns, certain rows, or both. In every example, though, the rows you get in the result are rows from the original table. Aggregate queries are those that generate data by combining the original rows via an aggregation function, usually SUM, COUNT, or AVG. Obviously the sum of two rows is one row, and is not identical to either of the original rows. The following query gives you the total dollar amount of all purchases in the table:

No matter how many rows were in the original table, the query above returns just one row. Say… how many rows are in the original table?

The COUNT function actually counts the number of non-null values in the specified column, not the number of unique values. If you used COUNT(seller_name) instead of COUNT(order_id) you’d get the same result. Even if you have five hundred listings from 25 sellers, the COUNT would be 500, not 25. If you have set up the table to allow nulls (empty or missing values) in the specified column, then you might get a result of less than 500. If you want to be sure to get exactly the total number of rows, simply use COUNT(*).

A grand total (or count, or average) is interesting, but a lot of the time what we want to do are compare subtotals (or counts, or averages) for various groupings of the data. To do this, we introduce a “GROUP BY” clause. If we want to know how many listings were made by each seller, we can group by the “seller_name” column and count up the rows in each group:

If you want to know which sellers are listing the biggest-ticket items, you might group by seller and take an average of the starting prices. There are a lot of sellers, though, so it’d helpful to sort the results with an “ORDER BY” clause. Since the average is the unnamed second column of the result set, that’ll be “ORDER BY 2”.

To get just the top ten, here’s a trick: sort the data in descending (“DESC”) order, and “LIMIT” the results to just the first ten rows.

In Chapter 2 and beyond you’ll learn a lot more SQL, such as how to create queries that “join” multiple tables, and how to write queries that employ nested sub-queries. Even in this example, though, you’ve seen several of the main parts of a SELECT query, including the “WHERE”, “GROUP BY”, and “ORDER BY” clauses, and aggregate queries. You have begun to see that even a simple one-table database may be queried in several different ways, and that doing this with short SQL queries may be much easier than trying to wrangle the data in Excel.

I recommend that you attempt the exercises and challenges at the end of this chapter to get more practice with the basics of relational databases, SQL, and PostgreSQL specifically.

Summary

A database serves as a respository for data and a system to manage it, a “single source of truth” that can mitigate problems organizations face when working with information—coordination, version control, and information security, to name a few. A database becomes a key piece of business infrastructure when numerous people and systems depend on it. Accordingly, the database typically operates as a server, a system that is always on, always ready to respond to requests from other systems. Database administrators are the professionals who engineer and maintain databases. There are many types of databases; this book focuses on the most popular and versatile type—the relational database. PostgreSQL is an increasingly popular, open-source, and cross-platform relational database that should serve us well as a platform for learning relational modeling and the SQL query language. These concepts are easy to transfer to other relational databases once you learn them

Definitions

- black box

- a term sometimes used to hypothesize a device by describing what it would do without addressing how it might actually work

- database

- (in common usage) a system that organizes and stores data and, importantly, makes it available to people and systems that need to search or retrieve it

- (more precisely) the structured data stored by such a system, which is created and accessed using a database management system (DBMS)

- (in PostgreSQL) a logical grouping of tables within a PostgreSQL server

- database administrator (DBA)

- a professional responsible for developing, securing, and maintaining the database(s) that an organization depends on

- database management system (DBMS)

- a software system used to create, manage, and query a database

- database server

- a database that operates as a server; PostgreSQL acts as a server even when installed on a personal computer

- display logic

- information or code that specifies how data is to be presented to a human user; unlike spreadsheets, database tables do not convey their own display logic

- document-oriented database

- a non-relational database type in which data is logically modeled as collections of “documents” with tree-like structures

- graph database

- a non-relational database type in which data is logically modeled as a network diagram (a mathematical graph) with nodes and edges

- metadata

- information about data’s structure and meaning; examples include column names and data types

- Postgres

- nickname for PostgreSQL

- PostgreSQL

- an advanced open-source RDBMS increasingly popular with software developers; freely available at www.postgresql.org

- primary key

- a column in a data table that is guaranteed to have a unique value for each row, and therefore allow us to retrieve a specific piece of data

- query

- (v) to request specified data from a database

- (n) a specification in code (e.g. SQL) of a request for data from a database

- relation

- a data “table” that conforms to a few criteria mentioned in this chapter and further detailed in Chapter 2

- relational database

- a database in which data is logically structured as a collection of relations (i.e. tables) and which conforms (more or less) to the principles proposed in E.F. Codd’s 1970 paper “A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks”

- relational database management system (RDBMS)

- a DBMS for a relational database; notable examples include PostgreSQL, MySQL, Oracle, SQL Server, DB2, and Access

- server

- a software or hardware system that is always on, waiting to respond to requests from users or other systems

- SQL

- the “structured query language”, a declarative language for querying an RDBMS; mostly standardized, there are minor differences in the SQL “dialect” used by different database brands

- table

- the commonly term for a relation in a database

New psql commands

- help

- display a list of the most basic

psqlcommands - \?

- list all

psqlcommands - \h

- list all SQL commands supported by PostgreSQL

- \c <database>

- switch to working in the specified database

- \dt

- list all tables in the current database

New SQL syntax

TBD

Challenges

- Look up and read an encyclopedia entry on databases. Did you learn anything that you think ought to have been included in this chapter? Email the author or leave feedback on Leanpub!

- Find and read the official PostgreSQL documentation on the “CREATE TABLE” command. What are some of the other rules or constraints you can place on a column? Name three, and speculate on when they would be useful.

- Look up the documentation on data types supported by PostgreSQL. There are a lot of them. Make a short list (or a cheat sheet) of the five or six data types you think you’d use most often.

- Try to find out on your own how to use the “ALTER TABLE” command to add a new column to an existing table. Specifically, add a “date” column to the “purchases” table used as an example in this chapter.

- PostgreSQL offers a graphical user interface (GUI) called pgAdmin, which may have been installed with it. Find this program on your computer or install it, and figure out how to log in to your PostgreSQL database(s) with it.

- On your own, figure out how to use pgAdmin to create a new table in the “auctagon” database. Make sure it has a primary key column (i.e., a unique ID number or code). Can you add some sample data to the table without having to use SQL “INSERT” commands?

- See if you can find out how to open a window within pgAdmin to execute arbitrary SQL commands. Run some of the example SQL queries from this chapter through that interface.

- Other graphical clients for PostgreSQL (besides pgAdmin) are available, some free (or free to students) and some commercial. Find and examine one or two of these alternatives. What do you think of them?

Exercises

TODO

Supplemental Lab 1: Creating FrienduLATER

A second case study that runs through this textbook is a database for a social networking application called FrienduLATER. In this lab, we’re starting with a single table that stores messages posted to a user’s “wall” or message board. You’ll want to be able to query for messages posted since the last time you logged in, in reverse chronological order, to query for messages from a specific subset of users, and perhaps to find out the number of unread messages and the last time a user was active. This lab and a video to accompany it are coming soon.

TODO

Think About It

- Not all databases are relational. How might you structure a database without using familiar tables, rows, and columns? What would be the advantages and disadvantages of such a data modeling approach?