Code conventions used in this book

The recipes in this cookbook are written as Jupyter notebooks, and follow their structure: blocks of explanatory text, like the one you’re reading now, are mixed with cells containing Python code (inputs) and the results of executing it (outputs). The code and its output—if any—are marked by In [N] and Out [N], respectively, with N being the index of the cell. You can see an example in the computations below:

In [1]: def f(x, y):

return x + 2*y

In [2]: a = 4

b = 2

f(a, b)

Out[2]: 8

By default, Jupyter displays the result of the last instruction as the output of a cell, like it did above; however, print statements can display further results.

In [3]: print(a)

print(b)

print(f(b, a))

Out[3]: 4

2

10

Jupyter also knows a few specific data types, such as Pandas data frames, and displays them in a more readable way:

In [4]: import pandas as pd

pd.DataFrame({ 'foo': [1,2,3], 'bar': ['a','b','c'] })

Out[4]:

| foo | bar | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | a |

| 1 | 2 | b |

| 2 | 3 | c |

The index of the cells shows the order of their execution. Jupyter doesn’t constrain it; however, in all of the recipes of this book the cells were executed in sequential order as displayed. All cells are executed in the global Python scope; this means that, as we execute the code in the recipes, all variables, functions and classes defined in a cell are available to the ones that follow.

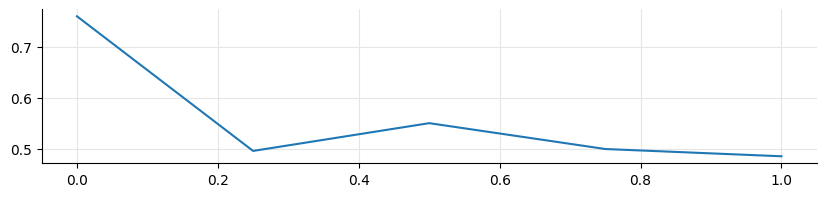

Notebooks can also include plots, as in the following cell:

In [5]: %matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import utils

f, ax = utils.plot(figsize=(10,2))

ax.plot([0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0], np.random.random(5))

Out[5]: [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7f615b41b3a0>]

As you might have noted, the cell above also printed a textual representation of the object returned from the plot, since it’s the result of the last instruction in the cell. To prevent this, cells in the recipes might have a semicolon at the end, as in the next cell. This is just a quirk of the Jupyter display system, and it doesn’t have any particular significance; I’m mentioning it here just so that you dont’t get confused by it.

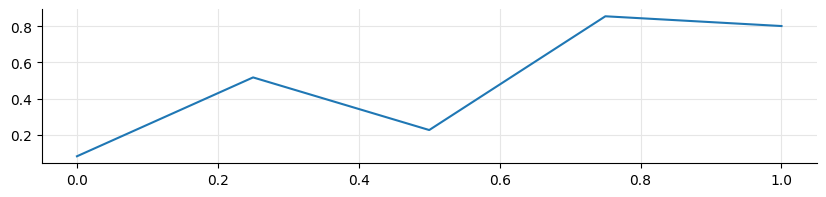

In [6]: f, ax = utils.plot(figsize=(10,2))

ax.plot([0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0], np.random.random(5));

Finally, the utils module that I imported above is a short module containing convenience functions, mostly related to plots, for the notebooks in this collection. It’s not necessary to understand its implementation to follow the recipes, and therefore we won’t cover it here; but if you’re interested and want to look at it, it’s included in the zip archive that you can download from Leanpub if you purchased the book.