Language fundamentals

In this section, I will demonstrate the basics of the Scala programming language. This includes things that are common to most programming languages as well as several features which are specific to Scala. I’m going to provide the output of the interpreter here, but feel free to start you own REPL session and try it yourself.

Defining values

There are three main keywords for defining everything in Scala:

| keyword | description |

|---|---|

val |

defines a constant (or value) |

var |

defines a variable, very rarely used |

def |

defines a method |

Defining a constant is usually as simple as typing

Notice that Scala guessed the type of the constant by analyzing its value. This feature is called type inference.

Sometimes you want to specify the type explicitly. If, in the example, above you want to end up with a value of type Short, simply type

Variables are rarely needed in Scala, but they are supported by the language and could be useful sometimes:

Just as with types, you may explicitly specify the type or allow the type inferrer to do its work.

When defining methods, it is required to specify argument types. Specifying the return type is recommended but optional:

It’s worth mentioning that the body doesn’t require curly braces and could be placed on the same line as the signature. At the same time, relying on the type inferrer for guessing the return type is not recommended for a number of reasons:

- If you rely on the type inferrer, it basically means that the return type of your function depends on its implementation, which is dangerous as implementation is often changed

- The readers of your code don’t want to spend time guessing the resulting type

These points are particularly important when you work on public APIs.

The return type can be specified after the parentheses:

The value that is returned from the method is the last expression of its body, so in Scala you don’t need to use the return keyword. Remember, however, that the assignment operator doesn’t return a value.

If you want to create a procedure-like method that doesn’t return anything and is only invoked for side effects, you should specify the return type as Unit. This is a Scala replacement for void (which, by the way, is not even a keyword in Scala):

It’s also possible to define a method without parentheses, in which case it is called a parameterless method:

This makes the invocation of such a method look like accessing a variable/constant and supports the uniform access principle. If you want to define your method like this, you should ensure that it doesn’t have side effects, otherwise it will be extremely confusing for users.

Functional types

It’s possible to define a function and assign it to a variable (or constant). For example, the greet method from the example above could also be defined in the following way:

As the REPL output shows, String => String is the type of our function. It can be read as a function from String to String. Again, you don’t have to type the return type, but if you want the type inferrer to do the work, you’ll have to specify the type of parameters:

Assigning methods to variables is also possible, but it requires a special syntax to tell the compiler that you want to reference the function rather than call it:

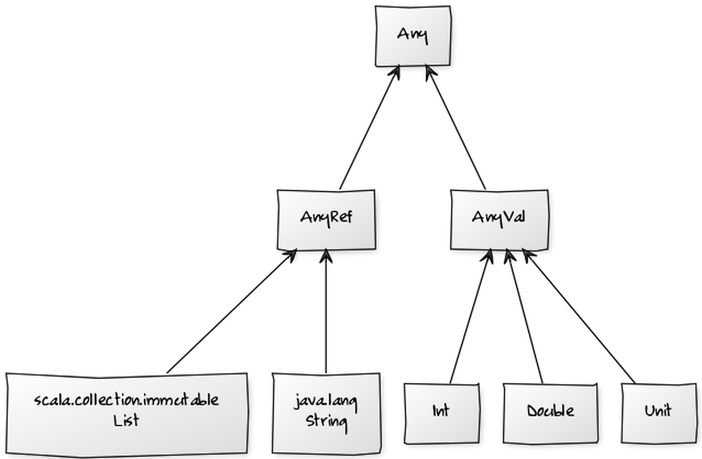

Type hierarchy

Since we are on the topic of types, let’s take a look at a very simplified type hierarchy:

Unlike Java, literally everything has its place here. Primitive types inherit from AnyVal, reference types (including user-defined classes) inherit from AnyRef. The absence of value has its own type Unit, which belongs to the primitives group. Even functions have their place in this hierarchy: for example, a function from String to String has type Function1[String, String]:

You can use isInstanceOf to check the type of a value:

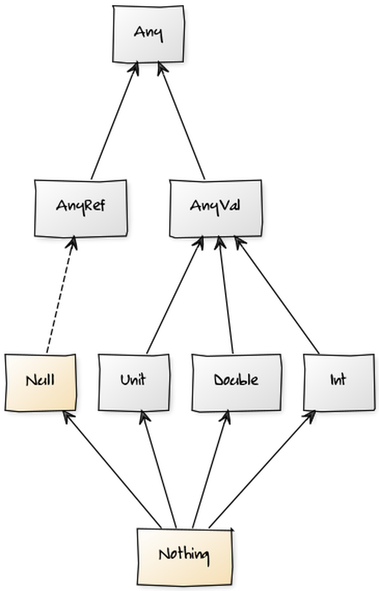

Scala also introduces the concept of so-called bottom types which implicitly inherit from all other types:

In the diagram above, Null implicitly inherits from all reference types (including user-defined ones, of course) and Nothing from all types including primitives and Null itself. You are unlikely to use bottom types directly in your programs, but they are useful to understand type inference. More on this later.

Collections

Unlike Java, Scala uses the same uniform syntax for creating and accessing collections. For example, you can use the following code to instantiate a new list and then get its first element:

For comparison, here is the same code that uses an array instead of a list:

For performance reasons, Scala will map the latter collection to a Java array. It happens behind the scenes and is completely transparent for a developer.

Another important point is that Scala collections always have a type. If the type wasn’t specified, it will be inferred by analyzing provided elements. In the example above we ended up with the list and array of Ints because the elements of these collections looked like integers. If we wanted to have, say, a list of Shorts, we would have to set the type explicitly like so:

If the type inferrer cannot determine the type of the collection, compilation will fail:

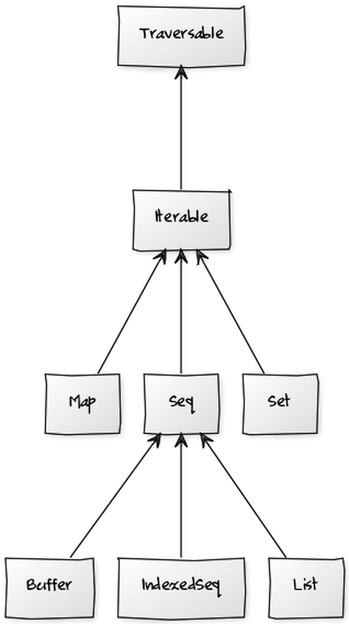

A greatly simplified Collections hierarchy is shown below:

It’s worth mentioning that most commonly used methods are already defined on very basic collection types. In practice, this means that when you need a collection, usually you can simply use Seq, and its API will probably be sufficient most of the time.

Collections also come in two flavours - mutable and immutable. Scala uses the immutable flavour by default, so when, in the previous example, we typed List, we actually ended up with an immutable List:

Immutable collections don’t have methods for altering the original collection, but they have methods that return new collections. For example, the :+ method returns a new list that contains all the elements of the original list and one new element:

Mutable collections can alter themselves. A great example of a mutable list is ListBuffer, which is often used to accumulate values and then build an immutable list from these values:

This is similar to using StringBuilder for constructing strings in Java.

Packages and imports

Scala classes are organized into packages similarly to Java or C#. For example, the ListBuffer type was defined in a package called scala.collection.mutable so in order to use it in your program you need to either always type a so-called fully qualified name (FQN for short) or import the class:

Just like in Java or C#, we can import all classes from a particular package using a wildcard. The difference is that Scala uses _ instead of *:

In addition to the imports defined by a developer, Scala automatically imports the following:

| import | description |

|---|---|

java.lang._ |

which includes String, Exception etc. |

scala._ |

which includes Option, Any, AnyRef, Array etc. |

scala.Predef |

which conveniently introduces aliases for commonly used types and functions such as List, Seq, println etc. |

Imports in Scala are not restricted to the beginning of the file and can appear inside functions or classes.

Defining classes

Users can define their own types using the omnipresent class keyword:

Needless to say, the Person class defined above is completely useless. You can create an instance of this class, but that’s about it:

Note that the REPL showed Person@794eeaf8 as a value of this instance. Why is that? Well, in Scala all user-defined classes implicitly extend AnyRef, which is the same as java.lang.Object. The java.lang.Object class defines a number of methods including toString:

def toString(): String

By convention, the toString method is used to create a String representation of the object, so it makes sense that REPL uses this method here. The base implementation of the toString method simply returns the name of the class followed by an object hashcode.

A slightly better version of this class can be defined as follows:

By putting name: String inside the parentheses we defined a constructor with a parameter of type String. Although it is possible to use name inside the class body, the class still doesn’t have a field to store it. Fortunately, it’s easily fixable:

Much better! Adding val in front of the parameter name defines an immutable field. Similarly var defines a mutable field. In any case, this field will be initialized with the value passed to the constructor when the object is instantiated. What’s interesting, the class defined above is roughly equivalent of the following Java code:

1 class Person {

2 private final String mName;

3 public Person(String name) {

4 mName = name;

5 }

6 public String name() {

7 return mName;

8 }

9 }

To define a method, simply use the def keyword inside a class:

1 class Person(val name: String) {

2 override def toString = "Person(" + name + ")"

3 def apply(): String = name

4 def sayHello(): String = "Hi! I'm " + name

5 }

In the example above we defined two methods - apply and sayHello and overrode (thus keyword override) existing method toString. Of these three, the simplest one is sayHello as it only prints a phrase to stdout:

Notice that REPL used our toString implementation to print information about the instance to stdout. As for the apply method, there are two ways to invoke it.

Yep, using parentheses on the instance of a class actually calls the apply method defined on this class. This approach is widely used in the standard library as well as in third-party libraries.

Defining objects

Scala doesn’t have the static keyword, but it does have syntax for defining singletons. If you need to define methods or values that can be accessed on a type rather than an instance, use the object keyword:

1 object RandomUtils {

2 def random100 = Math.round(Math.random * 100)

3 }

After RandomUtils is defined this way, you will be able to use method random100 without creating any instances of the class:

You can define the apply method on an object and then call it using the name of the object followed by parentheses. One common pattern is to define an object that has the same name as the original class and define the apply method with the same constructor parameters as the original class:

1 class Person(val name: String) {

2 override def toString = "Person(" + name + ")"

3 }

4 object Person {

5 def apply(name: String): Person = new Person(name)

6 }

Now you can use the apply method on the object to create instances of class Person:

Essentially, this eliminates the need for using the new keyword. Again, this approach is widely used in the standard library and in third-party libraries. In later chapters, I usually refer to this syntax as calling the constructor even though it is actually calling the apply method on a companion object.

Type parametrization

Classes can be parametrized, which makes them more generic and possibly more useful:

1 class Cell[T](val contents: T) {

2 def get: T = contents

3 }

We defined a class called Cell and specified one field contents. The type of this field is not yet known. Scala doesn’t allow raw types, so you cannot simply create a new Cell, you must create a Cell of something. Fortunately, the type inferrer can help with that:

Here we passed 1 as an argument, and it was enough for the type inferrer to decide on the type of this instance. We could also specify the type ourselves:

Collections syntax revisited

Now it’s becoming more and more clear that there is absolutely nothing in Scala syntax that is specific to collections. In fact, now we can explain what happens behind the scenes when we are creating and accessing Lists:

First, we can conclude that List is a parametrized class that has the apply method. This method accepts an index as an argument and returns the element that has this index. Second, there is also an object called List which has the apply method. This method probably calls the List constructor to instantiate the actual object. Finally, the toString method is overridden to return the word List and its elements in parentheses.

Functions and implicits

A parameter of a function can have a default value. If this is the case, users can call the function without providing the value for the argument:

Compiler sees that the argument is absent, but it also knows that there is a default value, so it takes this value and then invokes the function as usual.

We can go even further and declare the name parameter as implicit:

Here we’re not setting any default values in the function signature. As a result, in the absence of the argument, Scala will look for a value of type String marked as implicit and defined somewhere in scope. So, if we try to call this function immediately, it will not work:

However, after defining an implicit value with a type of String, it will:

This code works because there is exactly one value of type String marked as implicit and defined in the scope. If there were several implicit Strings, the compilation would fail due to ambiguity.

Implicits and companion objects

You can define your own implicit values or introduce already defined implicits into scope by means of imports. However, there is one more place where Scala will look for an implicit value when it needs one. This is the companion object of the parameter type. For example, when we are defining a new class called Person, we may decide to create a default value and put it into the companion object:

1 class Person(val name: String)

2

3 object Person {

4 implicit val person: Person = new Person("User")

5 }

Let’s also create a method with one parameter of type Person and mark it as implicit:

def sayHello(implicit person: Person): String = "Hello " + person.name

Even if we don’t create any instances of class Person in the scope, we will still be able to use the sayHello method without providing any arguments:

This works because companion objects are another place where the compiler looks for implicits. The point here is that the type of the method parameter is the same as the name of the companion object.

Of course, we can always pass a regular argument explicitly:

In this case, the explicitly passed parameter takes precedence over whatever implicit parameter was defined. Remember that the compiler only starts looking for implicits if it cannot validate code using regular arguments.

Loops and conditionals

Unlike Java with its if-statements, in Scala if-expressions always result in a value. In this respect, they are similar to Java’s ternary operator ?:.

Let’s define a function that uses the if expression to determine whether the argument is an even number:

1 def isEven(num: Int) = {

2 if (num % 2 == 0)

3 true

4 else

5 false

6 }

When this method is defined in REPL, the interpreter responds with isEven: (num: Int)Boolean. Even though we haven’t specified the return type, the type inferrer determined it as the type of the last (and only) expression, which is the if expression. How did it do that? Well, by analyzing the types of both branches:

| expression | type |

|---|---|

| if branch | Boolean |

| else branch | Boolean |

| whole expression | Boolean |

If an argument is an even number, the if branch is chosen and the result type has type Boolean. If an argument is an odd number, the else branch is chosen but result still has type Boolean. So, the whole expression has type Boolean regardless of the “winning” branch, no rocket science here.

But what if branch types are different, for example Int and Double? In this case the nearest common supertype will be chosen. For Int and Double this supertype will be AnyVal, so AnyVal will be the type of whole expression.

If you give it some thought, it makes sense, because the result type must be able to hold values of both branches. After all, we don’t know which one will be chosen until runtime.

Bottom types revisited

Now it’s time to recall two types which reside at the bottom of the Scala type hierarchy - Null and Nothing.

There is only one object of type Null - null and its meaning is the same as it was in Java or C#: the object is not initialized. Any reference object can be null, so it’s only logical that any reference type (i.e AnyRef) is a supertype of Null. This brings us to the following conclusion:

| expression | type |

|---|---|

| if branch | AnyRef |

| else branch | Null |

| whole expression | AnyRef |

In other words, if the else branch returns null, the if branch determines the result of the whole expression.

OK, what if the else branch never returns and instead, throws an exception? In this case, the type of the else branch is considered to be Nothing, and the whole expression will have the type of the if branch.

| expression | type |

|---|---|

| if branch | Any |

| else branch | Nothing |

| whole expression | Any |

There’s not much you can do with bottom types, but they are included in Scala hierarchy, and they make the rules that the type inferrer uses more clear.

while loops

The while loop is almost a carbon copy of its Java counterpart, so in Scala it looks like an outcast. Instead of returning a value, it’s called for a side effect. Moreover, it almost always utilizes a var for iterations:

1 var it = 5

2 while (it > 0) {

3 print(it)

4 it -= 1

5 }

6 // prints 54321

It feels almost awkward to use it in Scala, and, as a matter of fact, you almost never need to. We will look at some alternatives when we get to the Functional programming section, but for now, here is more Scala-like code that does essentially the same thing:

1.to(5).reverse.foreach { num => print(num) }

// prints 54321

String interpolation

String interpolation was one of the features introduced in Scala 2.10. It allows to execute Scala code inside string literals. In order to use it, simply put s in front of a string literal and $ in front of any variable or value you want to interpolate:

1 val name = "Joe"

2 val greeting = s"Hello $name"

3 println(greeting)

4 // prints Hello Joe

If an interpolated expression is more complex, e.g contains dots or operators, it needs to be taken in curly braces:

1 val person = new Person("Joe")

2 val greeting = s"Hello ${person.name}"

3 println(greeting)

4 // prints Hello Joe

If you need to spread your string literal across multiple lines or include a lot of special characters without escaping you can use triple-quote to create raw strings:

1 val json = """

2 {

3 firstName: "Joe",

4 lastName: "Black"

5 }

6 """

Note that the usual backslash escaping doesn’t work there:

1 val str = """First line\nStill first line"""

2 println(str)

3 // prints First line\nStill first line

This makes sense because the whole idea of raw string is to treat characters for what they are.

Traits

Traits in Scala are similar to mixins in Ruby in a sense that you can use them to add functionality to your classes. Traits can contain both abstract (not implemented) and concrete (implemented) members. If you mix in traits with abstract members, you must either implement them or mark your class as abstract, so the Java rule about implementing interfaces still holds.

Unlike Java interfaces, though, Scala traits can and often do have concrete methods.

Let’s look at a rather simplistic example:

1 trait A { def a(): Unit = println("a") }

2

3 trait B { def b(): Unit }

We defined two traits so that trait A has one concrete method, and trait B has one abstract method (the absence of a body that usually comes after the equals sign means exactly that). If we want to create a new class C that inherits functionality from both traits, we will have to implement the b method:

class C extends A with B { def b(): Unit = println("b") }

If we don’t implement b, we will have to make the C class abstract or get an error.