Functional programming

In this section, we will examine a number of features which support functional programming and are available in Scala. As we will see, all of them are actively used by library designers and developers in real-world applications.

Algebraic data types

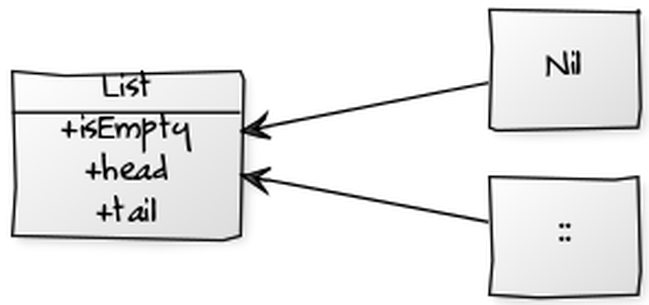

Even though it sounds like rocket science, algebraic data types (ADT) are actually pretty simple. An ADT is a type formed by combining other types. For example, List is an ADT, because it’s formed by combining two other types - empty list (represented by singleton object Nil) and non-empty list (represented by :: and pronounced cons):

The important thing here is that the list may be either empty or non-empty, i.e Nil and :: form disjoint sets. In addition to using the List object’s apply method, you can use the following approach to construct a new list:

val list = 1 :: 2 :: 3 :: Nil

The :: method is called prepend and it’s available on all lists including the empty one. In Scala, if a method’s name ends with a colon (:), the argument of this method (when the method invocation is written in the operator style, i.e, without dots and parentheses) must be placed on the left. With this little trick in mind, we can rewrite the previous example like so:

val list = Nil.::(3).::(2).::(1)

Basically, we start with the empty list Nil and then prepend the numbers so that the resulting list will be List(1, 2, 3).

In order to determine the type of the list, we could use the isInstanceOf method available on all types:

1 list.isInstanceOf[List[Any]] // true

2 list.isInstanceOf[Nil.type] // false

3 list.isInstanceOf[::[Int]] // true

As Martin Odersky usually puts it, the instanceOf method is made verbose intentionally to discourage people from using it too often. A more Scala-like approach is to use pattern matching.

Pattern matching

You can think of pattern matching as Java’s switch statement on steroids. The main differences are that pattern matching in Scala always returns a value and it is much more powerful.

1 list match {

2 case Nil => println("empty")

3 case ::(head, tail) => println("non-empty")

4 }

The first case block simply checks whether the list object is the Nil singleton object. The second one is more interesting, though. Not only does it check that the list has type ::, it also extracts head (the first element) and tail (all elements except the first one).

Scala also allows to use infix notation for destructuring constructor arguments, so the previous example can also be written as follows:

1 list match {

2 case Nil => println("empty")

3 case head :: tail => println("non-empty")

4 }

Since it’s not really our goal here, we’re not going to get into mechanics that make pattern matching possible. However, it’s worth mentioning that if you want your class to have similar capabilities, you must provide the unapply method on the companion object. Alternatively, you can simply turn your class into a case class, and then, the unapply method will be created automatically.

Case classes

Remember our Person class from the section about objects? Let’s revisit that code here:

1 class Person(val name: String) {

2 override def toString = "Person(" + name + ")"

3 }

4 object Person {

5 def apply(name: String): Person = new Person(name)

6 }

Here we’re creating a class, defining a field, overriding the toString method, defining a companion object. All of this could be achieved by the following line:

case class Person(name: String)

On top of the goodies mentioned above, this definition also does the following:

- overrides the

hashcodemethod used by some collections from the standard library - overrides the

equalsmethod, which makes two objects with the same set of values equal, sonew Person("Joe") == new Person("Joe")will returntrue - defines the

unapplymethod used in pattern matching

If we create an instance of the Person class, we can pattern match against it:

1 val person = Person("Joe")

2

3 person match {

4 case Person(name) => s"Hello $name"

5 case _ => "Not a person!"

6 }

The _ symbol defines a so-called catch-all case that will be chosen if all previous cases failed to match the expression.

The Person type also received well-behaved toString and equals methods:

1 val person = Person("Joe")

2 println(person)

3 // prints Person(Joe)

4

5 val personClone = Person("Joe")

6 println(personClone == person)

7 // prints true

As a result, many developers use case classes to quickly get hassle-free types with hashcode, equals and apply methods even if they don’t intend to use their classes in pattern matching.

Higher-order functions

Functions that accept other functions as their arguments are called higher-order functions. They are supported by virtually any modern programming language including JavaScript, Ruby, Python, PHP, Java, C# and so on. Since they are such a common concept, which is probably already familiar to you, we’re not going to spend much time discussing the theory behind higher-order functions. Instead, we will look at some Scala specifics.

Curly braces instead of parentheses

If your function accepts only one argument, then you are free to call your function using curly braces instead of parentheses:

It may not be that useful when the only argument is a String, but what if the function accepts another function as the argument? If we had to always use parentheses, there would be too many of them:

But since the invokeBlock method accepts only one argument, we can use the following syntax:

1 invokeBlock { () =>

2 println("Inside the block!")

3 }

The block spreads to several lines, and using curly braces makes the code actually look like a DSL (Domain-Specific Language).

map, filter, foreach

Let’s create a simple list that we will use to demonstrate common higher-order functions from the Collections API:

val list = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

Arguably, the most used method in the entire Collection API is map. It accepts a function that will be applied to each collection element, one by one. For example:

1 val squares = list.map { el => el * el }

2 println(squares)

3 // prints List(1, 4, 9, 16)

Here each element is multiplied by itself. Note that the original list stays untouched because instead of changing it, map returns a new list with updated values.

Another method is filter, which allows to keep only those elements that satisfy the condition:

1 val even = list.filter { el => el % 2 == 0 }

2 println(even)

3 // prints List(2, 4)

Here we created a new collection containing only even numbers.

If we don’t need a new collection, but instead we want to perform some action on each element, we can use foreach:

1 list.foreach { el => print(el) }

2 // prints 1234

Here we’re simply printing each element’s value.

flatMap

Suppose that we have two lists:

1 val list = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

2 val list2 = List("a", "b")

What if we wanted to combine each element of the first list with each element of the second list?

We could try to solve this task by nesting two maps:

1 val result = list.map { el1 =>

2 list2.map { el2 =>

3 el1 + el2

4 }

5 }

The resulting collection will have the following elements:

1 println(result)

2 // prints List(List(1a, 1b), List(2a, 2b), List(3a, 3b), List(4a, 4b))

The result has a type of List[List[String]], so we ended up with a list of lists. Not quite what we expected, right? The problem here is the external map. If you look at the Scala documentation, you will see that the map method accepts a function that takes one element and returns another element. On the other hand, we want to pass a function that takes an element and returns a list. Is there such a function defined on List? It turns out that yes, and it’s called flatMap. Using flatMap the problem can be solved easily:

1 val result = list.flatMap { el1 =>

2 list2.map { el2 =>

3 el1 + el2

4 }

5 }

The result is exactly what we needed:

1 println(result)

2 // List(1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, 3b, 4a, 4b)

Note that the result has a type of List[String], so it’s a flattened version of the list we received previously.

for comprehensions

In order to simplify writing expressions that use map, flatMap, filter and foreach, Scala provides so-called for comprehensions. Often for comprehensions make your code clearer and easier to understand.

Let’s rewrite the previous examples with for expressions:

1 for { el <- list } yield el * el // List(1, 4, 9, 16)

2 for { el <- list if el % 2 == 0 } yield el // List(2,4)

3 for { el <- list } println(el) // prints 1234

The yield keyword is used when the whole expression returns a value. With foreach, however, we are simply printing values on the screen, thus there’s no yield keyword.

The flatMap example translates into the following:

1 for {

2 el1 <- list

3 el2 <- list2

4 } yield el1 + el2

In my opinion, the last snippet can be easily understood even by people who don’t know what flatMap is and even that this function exists. Another interesting feature of this syntax is that it removes nesting: no matter how many lists we want to combine, we can put all of them into a single for expression.

For comprehensions are the central part of the Scala programming language. They are used in many situations, and you will see a lot of examples with the for keyword throughout this book.

Currying

A curried function is a function that has each of the parameters in its own pair of parentheses. The process of transforming a regular function into a curried one is called currying. A simple function that sums two integers

def sum(a: Int, b: Int): Int = a + b

can be transformed into the following curried function:

def sum(a: Int)(b: Int): Int = a + b

If the function is curried, it must be called with each argument in its own pair of parentheses:

1 val result = sum(2)(2)

2 println(result)

3 // prints 4

foldLeft

The foldLeft method from the Collections API is a curried method that takes two parameters. First parameter - the initial value - is used as the staring point of a computation, and the second parameter is a function that describes how to compute the next value using the previous one and the accumulator. It may sound terribly complicated, but in reality foldLeft is absolutely straightforward to use.

For example, we can use foldLeft to calculate the sum of elements in our list - List(1,2,3,4):

1 val sum = list.foldLeft(0) { (acc, next) =>

2 acc + next

3 }

4 println(sum)

5 // prints 10

Here we replaced parentheses around the second argument with curly braces to make it look like a proper function.

Laziness

By default, all values in Scala are initialized eagerly at the moment of declaration. This approach is widely known and in many programming languages there is no other way. In Scala, however, values can be initialized lazily, which means they remain uninitialized until the first use.

Let’s create a fictional service that we will use for demonstration:

1 class ConnectionService {

2 def connect = println("Connected")

3 }

The ConnectionService has only one method. Obviously, the service must be instantiated somewhere before it’s used. The following code reminds us that the order of initialization matters:

1 var service: ConnectionService = null

2 val serviceRef = service

3 service = new ConnectionService

4 serviceRef.connect

The code will fail at runtime with NullPointerException because when we declared the serviceRef, the service itself hadn’t been initialized. Ironically, when we first tried to use it, the service was up and running, so the problem was the order of initialization, not the service being uninitialized. If only we could postpone the initialization of serviceRef! It turns out that in Scala we can do exactly that by putting the lazy keyword in front of the val declaration (line 2).

2 lazy val serviceRef = service

In this case, the serviceRef is not initialized until serviceRef first referenced. By this time, the service is already up and running, so everything works fine.

Option

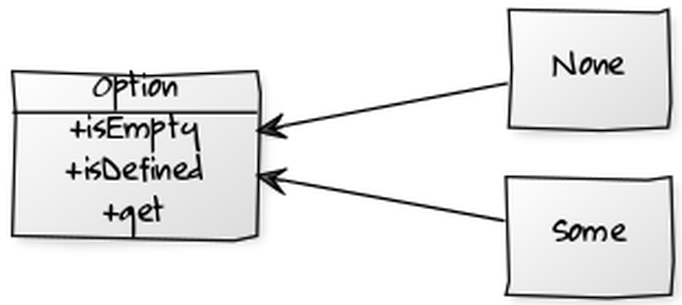

Option is a container that may or may not contain a value. It is another example of an algebraic data type, because it is formed by two subtypes: None and Some.

Options are a great way to show that a particular value may be absent. Essentially, this allows Scala developers to always avoid NullPointerExceptions if they play by the rules. Options are used everywhere in the standard library, in third-party libraries and they should be used in user code as well.

The safest way to create a value of type Option is to specify the type and then pass the value as the only argument:

1 val opt = Option[String]("Joe")

2 println(opt)

3 // prints Some(Joe)

This way, you can guarantee that the type will be Option[String] and you never end up with the null values inside. Even if you pass null, you will get None:

1 val opt = Option[String](null)

2 println(opt)

3 // prints None

In many situations, you can also pass a value in Some, but this approach doesn’t guarantee that the type will be what you expect:

1 val opt = Some(1)

2 // opt: Some[Int] = Some(1)

In the example above, we expected to get a more generic Option[Int] but instead, received a more narrow Some[Int]. Moreover, we may end up with nulls inside, which is a very dangerous situation and brings back the possibility of NullPointerExceptions:

1 val opt = Some(null)

2 // opt: Some[Null] = Some(null)

There are lots and lots of methods on the Option class, which makes Options such a pleasure to work with. Here are only some of them:

| method | description |

|---|---|

isDefined |

checks whether the value is present |

isEmpty |

checks whether the value is absent |

getOrElse |

returns the value if it’s there or the provided default value if it’s not |

get |

returns the value if it’s there or throws an exception if it is not; very rarely used |

map |

allows to transform one option into another |

foreach |

allows to use existing value without returning anything |

Let’s look at one concrete example to see how options are used. Suppose that we have a map that may contain information about the user.

Here we’re interested in two particular keys firstName and lastName and we want to use them to construct a value for full name.

1 val data = Map(

2 "firstName" -> "Joe",

3 "lastName" -> "Black"

4 )

5 // data: Map[String, String]

The apply method on Map returns the value associated with the requested key if the key is present. If it’s not, apply throws an exception. So, if we know for sure that this map contains both keys, constructing the full name is trivial:

val fullName = data("firstName") + " " + data("lastName")

If we don’t know what information is inside the map, then we need to use the get method, which returns an Option.

1 val maybeFirstName = data.get("firstName")

2 // maybeFirstName: Option[String]

3 val maybeLastName = data.get("lastName")

4 // maybeLastName: Option[String]

We cannot concatenate two Options as we would Strings, but we can obtain Strings by using the get method on Option:

1 val maybeFullName = if (maybeFirstName.isDefined &&

2 maybeLastName.isDefined) {

3 Some(maybeFirstName.get + " " + maybeLastName.get)

4 } else None

When working with Options in this way, we must first check whether the value actually exists and then use the get method. This approach, however, feel cumbersome, and we can definitely do better than that.

A slightly more Scala-like approach would involve pattern matching:

1 val maybeFullName = (maybeFirstName, maybeLastName) match {

2 case (Some(firstName), Some(lastName)) =>

3 Some(firstName + " " + lastName)

4 case _ => None

5 }

Here we’re grouping two values together by enclosing them in parentheses. Then we match the newly created pair against two case blocks. The first block works if both Options have type Some and therefore contain some values inside. The second catch-all case is used if either Option is actually None.

We can also achieve the same result by using map/flatMap combination:

1 val maybeFullName = maybeFirstName.flatMap { firstName =>

2 maybeLastName.map { lastName =>

3 firstName + " " + lastName

4 }

5 }

Doesn’t it look familiar? It certainly does! When we were working with lists, we found out that this construct can be written as a for comprehension:

1 val maybeFullName = for {

2 firstName <- maybeFirstName

3 lastName <- maybeLastName

4 } yield firstName + " " + lastName

5

6 println(maybeFullName)

7 // prints Some(Joe Black)

Great, isn’t it? This looks almost as straightforward as String concatenation. Please, memorize this construct, because as we will see later, it is used in Scala for doing a great deal of seemingly unrelated things like working with dangerous or asynchronous code.

Try

Let’s write a fictitious service that works roughly 60% of the time:

1 object DangerousService {

2 def queryNextNumber: Long = {

3 val source = Math.round(Math.random * 100)

4 if (source <= 60)

5 source

6 else throw new Exception("The generated number is too big!")

7 }

8 }

If we start working with this service directly without taking any precautions, sooner or later our program will blow up:

To work with dangerous code in Scala you can use try-catch-finally blocks. The syntax slightly differs from Java/C#, but the main idea is the same: you wrap dangerous code in the try block, and then, if an exception occurs, you can do something about it in the catch block.

1 val number = try {

2 DangerousService.queryNextNumber

3 } catch { case e: Exception =>

4 e.printStackTrace

5 60

6 }

The good news about try blocks in Scala is that they return a value, so you don’t need to define a var before the block and then assign it to some value inside (this approach is extremely common in Java). The bad news is that even if you come up with some reasonable value to return in case of emergency, this will essentially swallow the exception without letting anyone know what has happened. In theory, we could return an Option, but the problem here is that None will not be able to store information about the exception.

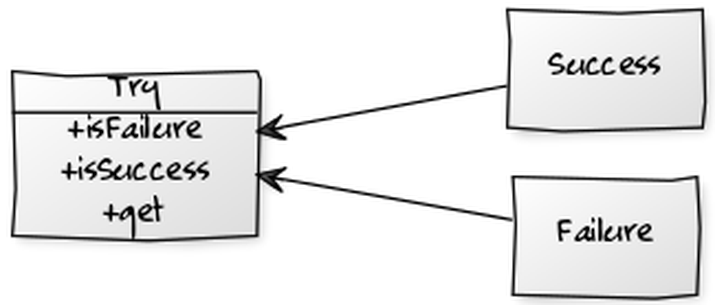

A better alternative is to use Try from the standard library. The Try type is an algebraic data type that is formed by two subtypes - Success and Failure.

The Try class provides many utility methods that make working with it very convenient:

| method | description |

|---|---|

isSuccess |

checks whether the value was successfully calculated |

isFailure |

checks whether the exception occurred |

get |

returns the value if it is a Success or throws an exception if it is a Failure; very rarely used |

toOption |

returns Some if it is a Success or None if it is a Failure

|

map |

allows to transform one Try into another |

foreach |

allows to use existing value without returning anything |

When working with Try, the dangerous code can be simply put in the Try constructor, which will catch all exceptions if any occur:

1 val number1T = Try { DangerousService.queryNextNumber }

2 val number2T = Try { DangerousService.queryNextNumber }

If we want to sum two values wrapped in Trys, we can use the already familiar flatMap/map combination:

1 val sumT = number1T.flatMap { number1 =>

2 number2T.map { number2 =>

3 number1 + number2

4 }

5 }

As always, we can write it as a for comprehension:

1 val sumT = for {

2 number1 <- number1T

3 number2 <- number2T

4 } yield number1 + number2

Note that a for comprehension yields the same container type (in our case Try) that was used initially. This happens because maps and flatMaps can merely transform the value inside the container, but they cannot change the type of the container itself. If, at some point, you need to convert a Try into something else, you will need to use utility methods but not maps or flatMaps.

Future

The final piece of the standard library that we are going to examine here is the Future class. Futures allow you to work with asynchronous code in a type-safe and straightforward manner without resorting to concurrent primitives like threads or semaphores.

Many methods defined on the Future class are curried and accept an implicit argument. For example, take a look at the map signature:

def map[S](f: (T) => S)(implicit executor: ExecutionContext): Future[S]

By defining the map method this way, the creators of the standard library basically allowed users to completely ignore the second parameter in most cases. Now we can simply declare (or import) an ExecutionContext and then work with Futures as if they were regular Scala containers like Options or Trys. In this case, necessary implicit resolution is happens behind the scenes and handled by the compiler.

The global ExecutionContext is already defined in the standard library and the only thing that’s left is to import it:

import scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.Implicits.global

Let’s add a pause to our service to make it slower and, therefore, simulate working with something very remote:

1 object DangerousAndSlowService {

2 def queryNextNumber: Long = {

3 Thread.sleep(2000)

4 val source = Math.round(Math.random * 100)

5 if (source <= 60)

6 source

7 else throw new Exception("The generated number is too big!")

8 }

9 }

If we try to use this service synchronously, our program, which uses this service, will be slowed down. In order to avoid it, we need to wrap our uses of the DangerousAndSlowService in a Future:

1 val number1F = Future { DangerousAndSlowService.queryNextNumber }

2 val number2F = Future { DangerousAndSlowService.queryNextNumber }

The important thing here is that both number1F and number2F will be initialized immediately. However, we will not be able to use the actual numbers until they are returned from the service.

The Future class provides many methods that you can use:

| method | description |

|---|---|

onComplete |

applies the provided callback when the Future completes, successfully or not |

onFailure |

applies the provided callback when the Future completes with an exception |

onSuccess |

applies the provided callback when the Future completes successfully |

mapTo |

casts the type of the Future to the given type |

map |

allows to transform one Future into another |

foreach |

allows to use existing value without returning anything |

In theory, it is possible to work with Futures relying solely on callbacks:

1 number1F.onSuccess { case number1 =>

2 number2F.onSuccess { case number2 =>

3 println(number1 + number2)

4 }

5 }

However, this approach makes code very complicated extremely quickly by introducing so-called callback hell. Besides, even after your callback is executed it’s usually not obvious how to communicate the result (or lack thereof) to the rest of the program.

A better solution is to utilize map and flatMap:

1 val sumF = number1F.flatMap { number1 =>

2 number2F.map { number2 =>

3 number1 + number2

4 }

5 }

And again, the same code could also be written as a for comprehension:

1 val sumF = for {

2 number1 <- number1F

3 number2 <- number2F

4 } yield number1 + number2

Usually, if you have only one container (Option, Try, Future, Seq and so on), it’s easier to simply use map. If you have several containers, for comprehensions will be a better choice.