2 What Are Microservices?

The idea behind Microservices is not new. A very similar approach is also followed by the UNIX philosophy, which is based on three ideas:

- A program should fulfill only one task, and it should do it well.

- Programs should be able to work together.

- Besides, the programs should use a universal interface. In UNIX these are text streams.

The realization of these ideas leads to the creation of reusable programs, which are in the end a kind of component.

Microservices serve to divide large systems. Consequently, Microservices represent a modularization concept. There is a large number of such concepts, but Microservices are different. They can be brought into production independently of each other. Changes to an individual Microservice only require that this Microservices has to be brought into production. In the case of other modularization concepts all modules have to be delivered together. Thus, a modification to an individual module necessitates that the entire application with all its modules has to be deployed again.

Microservice = Virtual Machine

Microservices cannot be implemented via the modularization concepts of programming languages. These concepts usually require that all modules have to be delivered together in one program. Instead Microservices have to be implemented as virtual machines, as more light-weight alternatives such as Docker containers or as individual processes. Thereby they can all easily be brought into production individually.

This results in a number of additional advantages: For instance, Microservices are not bound to a certain technology. They can be implemented in any programming language or on any platform. Moreover, Microservices can of course also bring along their own supporting services such as databases or other infrastructure.

Besides, Microservices should possess their own separate data storage i.e. a separate database or at least a separate schema in a common database. Consequently, each Microservice is in charge of its own data. In fact, experience teaches that the shared use of database schemas renders changes to the data structures practically impossible. Since this interferes profoundly with software changeability, this kind of coupling should be prevented.

Communication Between Microservices

Microservices have to be able to communicate with each other. This can be achieved in different manners:

- The Microservices can replicate data. This does not just mean to copy the data without changing the schema. In that case changes to the scheme are impossible because multiple Microservices use the same schema. However, when one Microservice processes orders and another analyzes the data of the orders, the data formats can be different and also access to the data is different: The analysis Microservice will primarily read data, for order processing reading and writing are rather equal. Classical data warehouses also employ replication for analyzing large amounts of data.

- When Microservices possess an HTML UI, they can easily use links to other Microservices. Besides, it is possible that a Microservice integrates the HTML code of other Microservices in its own web page.

- Finally, the Microservices can communicate with each other by protocols like REST or messaging via the network.

In a Microservice-based system it has to be defined which communication variants are used to ensure that the Microservices can in fact be reached with these technologies.

2.1 Size

The term “Microservice” focuses on the size of Microservices. This makes sense for distinguishing Microservices from other definitions of “services”. Nevertheless, it is not so easy to indicate the concrete size of Microservices.

Defining the unit poses already a problem: Lines of Code (LoC) are not a good unit. In the end, the actual number of Lines of Code of a program does not only depend on its formatting, but also on the programming language. In fact, it does not seem to make much sense to evaluate an architectural approach based on such metrics. Ultimately, the size of a system can hardly be given in absolute terms, but only in relation to the represented business processes and their complexity.

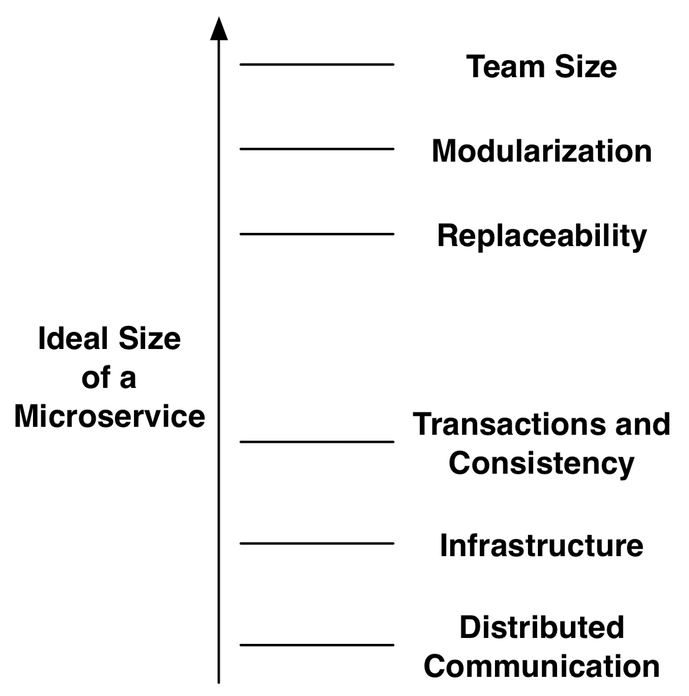

Therefore, it makes much more sense to define the size of Microservices with the aid of upper and lower limits. In general, it holds true that smaller is better for Microservices:

- A Microservice should be developed by one team. Therefore, a Microservice should never be so large that more than one team is necessary to develop it further.

- Microservices represent a modularization approach. Developers should be able to understand individual modules – therefore modules and thus Microservices have to be so small that an individual developer is still able to comprehend them.

- Finally, a Microservice should be replaceable. When a Microservice cannot be maintained anymore or for instance a more powerful technology is supposed to be used, the Microservice can be replaced by a new implementation. Microservices represent therefore the only software architecture approach which takes a future replacement of the system or at least of system parts already into consideration during development.

This leaves the question why not to just build the Microservices as small as possible. In the end, the advantages reinforce each other when the Microservices are especially small. However, there are different reasons why Microservices cannot be tiny without creating also a number of problems:

- Distributed communication between Microservices via the network is expensive. When Microservices are large, the communication occurs rather locally within a Microservice and is therefore faster and more reliable.

- It is difficult to move code across Microservice boundaries. The code has to be transferred into another system. When this system uses a different technology or programming language, rewriting the code in a different language might be the only option for moving a functionality from one Microservice into another. Of course, it is always possible to turn the respective functionalities into a new Microservice, which can be accessed by the other Microservices. In contrast, within a Microservice refactoring is quite easy with the aid of the usual mechanisms e.g. automated refactoring in the IDE.

- A transaction within a Microservice is easy to implement. Beyond the boundaries of an individual Microservice this is not trivial anymore since distributed transactions become necessary. Therefore the best is to decide for a Microservice size which allows that a transaction can be entirely processed in one Microservice.

- The same holds true for the consistency of data: When for instance the account balance is supposed to be consistent with the result of earnings and expenses, this can quite easily be implemented in one Microservice, but is hardly feasible across Microservices. Therefore, Microservices should be large enough to ensure that data which have to be consistent are handled in the same Microservice.

- Each Microservice has to be brought into production independently and therefore needs its own environment. This uses up hardware resources and means in addition that the effort for system administration increases. When there are larger and therefore fewer Microservices, this expenditure becomes smaller.

To a certain degree the size of a Microservice depends on the infrastructure: When the infrastructure is very simple, it can support a multitude of Microservices and therefore also very small Microservices are possible. In such a case the advantages of a Microservice-based architecture are accordingly larger. Already relatively simple measures can help to reduce the infrastructure expenditure: When there are templates for Microservices or other possibilities to create Microservices easily and to more uniformly administrate them, this can already reduce expenditure and thereby enable the use of smaller Microservices.

Nanoservices

Certain technological approaches can further reduce the size of a service. Instead of delivering Microservice as virtual machines or Docker containers, the services can be deployed on Amazon Lambda. It allows the deployment of individual functions written in Java, Node.js or Python. Each function is automatically monitored. In addition, each call to a function is billed. Functions can be called using REST or due to events e.g. data written to Amazon S3 or DynamoDB. Using such an infrastructure makes it possible to create services that just consist of a few Lines of Code each because the overhead for deployment and operations is so low.

A similar approach can be implemented using a Java EE application server. Java EE defines different deployment formats and allows to run multiple applications on an application server. The services communicate for instance via REST or messaging just like Microservices. However, in such a scenario the services are not so well isolated from each other anymore: When an application in an application server uses up a lot of memory, this will also affect the other applications on the application server.

Another alternative are OSGi bundles. This approach also defines a module system based on Java. However, in contrast to Java EE this approach allows method calls between bundles so that communication via REST or messaging is not necessarily required.

Unfortunately, both approaches are problematic when it comes to independent deployment: In practice, Java EE application servers and also OSGi runtime environments have often to be started again when new modules are deployed. Therefore, a deployment affects also other modules.

On the other hand, the expenditure for infrastructure and communication is lower since OSGi allows for instance to use local method calls. This enables the use of smaller services.

To clearly distinguish these services from Microservices it is sensible to use an alternative term like “Nanoservices” for this approach. Ultimately these services offer neither the isolation of Microservices nor their independent deployment.

2.2 Bounded Context and Domain-Driven Design

It is one of the main objectives of Microservices to limit changes and new features to one Microservice. Such changes can comprise the UI – therefore a Microservice should also provide a UI. However, also in another area modifications should occur within the same Microservice – namely in regards to data.

A service which implements an order process should ideally also be able to query and modify the data for an order. Microservices have their own data storage and can therefore store data in the way that best suits them. However, an order process requires more than just the data of the order. Also the data concerning the customer or the items are relevant for the order process.

Here, Domain-driven Design ((DDD)1) is helpful. Domain-driven Design serves to analyze a domain. The essential basis is Ubiquitous Language. This is like other components of Domain-driven Design also a pattern and therefore here set in italics. Ubiquitous Language denotes the concept that everybody who participates in the software should use the same terms. Technical terms like order, bill etc. should be directly echoed in the software. Often enterprises have their own specific language – this language should then also be implemented in the software.

The domain model can consist of different elements:

- Entity is an object with its own identity. In an E-commerce application the customer or the item could be Entities. Entities are typically stored in a database.

- Value Objects do not have their own identity. An example is an address which only makes sense in the context of a specific customer and therefore does not possess an identity.

- Aggregates are composite domain objects. They enable a simpler handling of invariants and other conditions. For instance, an order can be an Aggregate of order lines. This allows for instance to ensure that the order of a new customer does not surpass a certain limit. The invariant has to be fulfilled via a calculation of values from the order lines so that the order as Aggregate can ensure these conditions.

- Services contain business logic. DDD focuses on the modeling of business logic as Entities, Value Objects and Aggregates. However, logic which accesses multiple of these objects cannot be modelled in one of these objects. For this purpose there are Services.

- Repositories serve to access the entirety of all Entities of a type. Typically, some kind of persistence, for example in a database, is what is used to implement a Repository.

The implementation of a domain model from these components and also the idea of Ubiquitous Language facilitate the design and development of object-oriented systems. However, it is not immediately clear which relevance DDD might have for Microservices.

Bounded Context

Domain-driven Design does not only provide a guideline for how a domain model can be implemented, but also for the relationships between domain models. Having multiple domain models initially appears unusual. After all, concepts like customer and order are central for the entire enterprise. Therefore, it seems attractive to implement exactly one domain model and to carefully consider all aspects of the model. This should make it easy to implement the software systems in the enterprise based on these elements.

However, Bounded Context states that such a general model cannot be implemented. Let’s take the customer of the E-commerce shop as an example: The delivery address of this customer is relevant in the context of the delivery process. During the order process, on the other hand, the specific preferences of the customer matter, and for billing the options for paying, for which the customer has deposited data, are most important – for example his/her credit card number or information for a direct debit.

Theoretically it might be possible to collect all this information in a general customer profile. However, this profile would then be extremely complex. Besides, in practice it would not be possible to handle it: When the data regarding one context change, the model needs to be changed and this will then concern all components which use the customer data model – and these can be numerous. In addition, the analysis needed to arrive at such a customer model would be so complex that it would be hard to achieve in practice.

Bounded Context and Microservices

Therefore a domain model is only sensible in a certain context – i.e. in a Bounded Context. For Microservices it makes the most sense to design them in a way that each Microservice corresponds to a Bounded Context. This provides an orientation for the domain architecture of Microservices. This design is especially important since a good domain architecture enables independent work on features. When the domain architecture ensures that each feature is implemented in an individual Microservice, the implementation of features can be uncoupled. Since Microservices can even be brought into production independently of each other, features cannot only be developed separately, but also rolled out individually.

The independent development of features also profits from the distribution in Bounded Contexts: When a Microservice is also in charge of a certain part of the data, the Microservice can introduce features without causing changes to other Microservices.

When for example in an E-commerce system a payment option via PayPal is supposed to be introduced, this requires only changes to the Microservice for billing thanks to Bounded Context. There the UI elements and the new logic are implemented. As the Microservice for billing administrates the data for the Bounded Context, only the PayPal data have to be added to the data of the Microservice. Changes to a separate Microservice, which administrates the data, are not necessary. Therefore, the Bounded Context is also an advantage in regards to changeability.

Relationships Between Bounded Contexts

In his book Eric Evans describes different manners how Bounded Contexts can work together. In the case of Shared Kernel for instance a shared Bounded Context can be used in which the shared data are stored. A radical alternative option is Separated Ways: Here, both Bounded Contexts use completely independent models. Anticorruption Layer uncouples two domain models. Thereby it is for instance possible to prevent that an old and hard to understand data model from a mainframe has to be used in the remainder of the system. With the aid of an Anticorruption Layer the data are transferred into a new, easily understandable representation.

Of course, depending on the model used for the relationships between the Bounded Contexts more or less communication between the teams working on the Microservices will be necessary.

In general, it is therefore conceivable that a domain model also comprises multiple Microservices. Maybe it is sensible in the example of the E-commerce system that the modeling of the basic data of a customer is implemented in one Microservice and only specific data are stored in the other Microservices – following the concept of Shared Kernel. However, in such a case more coordination between Microservices might be necessary which can interfere with their separate development.

2.3 Conway’s Law

Conway’s Law was coined by the American computer scientist Melvin Edward Conway and states:

The reason behind Conway’s Law is that each organizational unit designs a certain part of the architecture. If two parts of the architecture are supposed to have an interface, coordination is required regarding this interface – and therefore a communication relationship between the organizational units which are responsible for the respective parts.

The Law as a Limit for Architecture

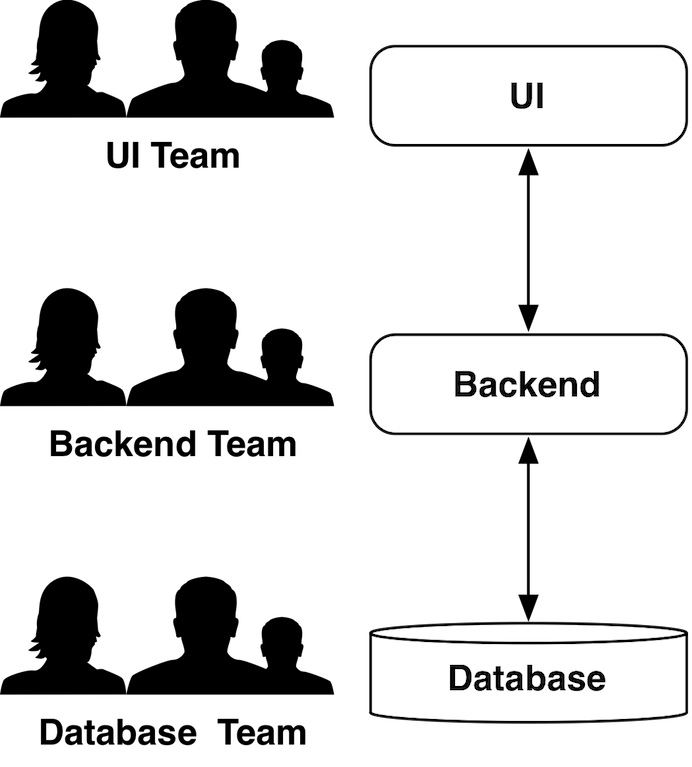

An example for the effects of the Law: An organization forms one team of experts each for the web UI, the logic in the backend and for the database (compare Fig. 2). This organization has advantages: The technical exchange between experts is relatively simple and holiday replacements are easy to organize. Therefore, the idea to have employees with similar qualification work together in one team is not very far fetched.

However, according to Conway’s Law the three teams will create artifacts in the architecture. A database layer, a backend layer and a UI layer will be created.

This architecture entails a number of disadvantages:

- To implement a feature, the customer has to talk with all three teams. He/she has to explain the requirements for the new feature to each of the three teams. When the customer does not have detailed knowledge about the system architecture, the teams will have to discuss with him/her how the functionalities can be implemented in the different layers.

- The teams have to coordinate their work for instance in regards to interfaces.

- In addition, it has to be ensured that each team delivers its part of the work in time. The backend can hardly implement new features without changes to the database. Likewise, the UI cannot be implemented without changes to the backend.

- The dependencies and the resulting need for communication slow down the implementation of the feature. The database team can only deliver the changes at the end of its sprint. As the work of the backend team is based on the changes introduced by the database team, it has to wait until the other team is done. Likewise, the UI team has to wait for the backend team to finish. Therefore, it might take three sprints until the entire implementation is completed. Of course, optimizations are possible. However, a completely parallel implementation is practically impossible.

The way the teams were created results therefore in an architecture which interferes with a faster implementation of features. This problem is often not perceived, as the relationship between organization and architecture is frequently not considered.

Conway’s Law as Enabler

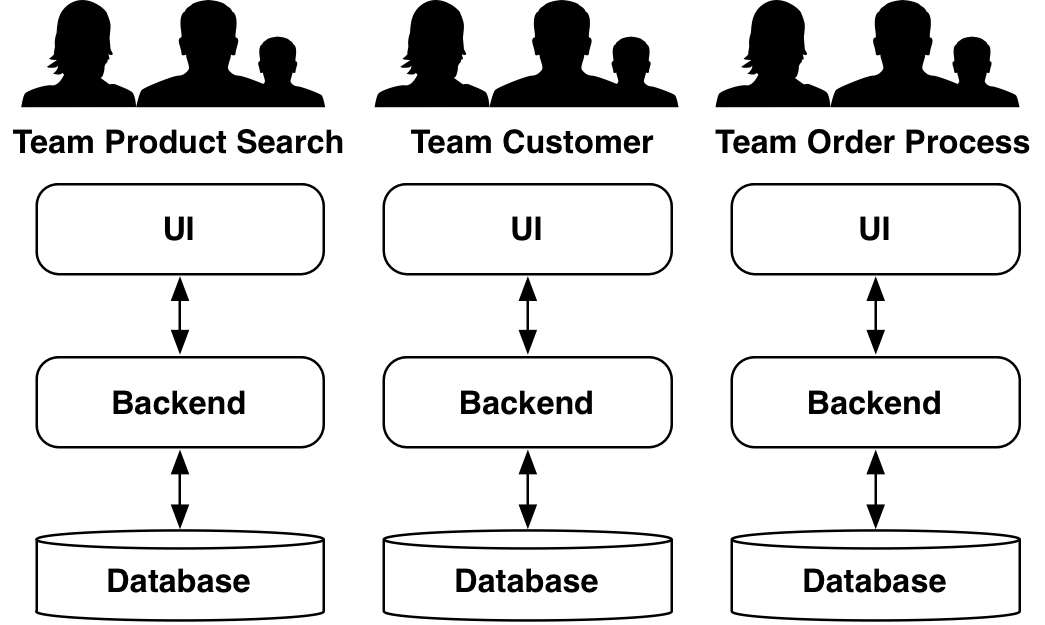

However, it is also possible to deal very differently with Conway’s Law. It is the explicit aim of Microservices to implement a domain architecture where each Microservice implements a meaningful part of the architecture e.g. a Bounded Context. That facilitates and parallelizes the work on domain aspects. Therefore, there is another way to handle Conway’s Law in the context of Microservices: Instead of letting the architecture be a result of the organization, the architecture drives the organization. The organization gets structured in the way that best supports the architecture.

Fig. 3 shows a possible architecture for a Microservice-based system: There is one component each for product search, the handling of customers and the order process. For each Microservice there is a team which implements this Microservice. Thereby the domain-based distribution into Microservices is not only implemented at the level of architecture, but also at the organizational level. This supports the architecture: Transgressing the architecture gets difficult because according to Conway’s Law the organization enforces a domain-based architecture.

Nevertheless, the different technical artifacts have to be implemented in the Microservices. Accordingly, the required technical skills have to be present in the different teams. Within a team the coordination of experts is profoundly easier than across teams. For this reason, requirements which have to be implemented across different technical artifacts are now easier to implement.

Organizational Compromises

In practice, even in a system structured as described with a supporting organization there are nevertheless still challenges to deal with. In the end, features are supposed to be implemented in the system. These features are sometimes not limited to one Microservice, but require changes to multiple Microservices. Besides, sometimes more changes have to be introduced into a Microservice than one team can handle. In practice, it has proven best to have one team in charge of a Microservice, but to allow also other teams to modify the Microservice. When a feature requires changes to multiple Microservices, one team can introduce all these changes without having to let changes be prioritized by another team. Besides, multiple teams can work on one Microservice in order to implement a greater number of features. Nevertheless, the team assigned to the Microservice is still in charge. In particular, it has to review all modifications to guide its development.

One Microservice per Team?

By the way, it is not really necessary that one team only implements one Microservice. A team can definitely also implement multiple Microservices. However, it is important that a team has a precisely defined responsibility in the domain architecture. In addition, one domain aspect should be implemented in as few Microservices as possible. It can definitely be desirable to implement smaller Microservices so that one team is in charge of more than one Microservice.

2.4 Conclusion

The discussion in section 2.1 about the size of Microservices focuses rather on the technical structure of the system for defining Microservices. For the distribution according to Bounded Context (section 2.2) the domain architecture is the most important aspect. Conway’s Law (section 2.3) states that Microservices also have effects on the organization. Only together these aspects give a faithful picture of Microservices. Which of these aspects is the most important depends on the use context of the Microservice-based architectures.