Chapter 7: Who’s Afraid of The Big Bad Waterfall?

Let’s take a break from the numbers game for a chapter or two, and examine some qualitative rather than quantitative claims. They’re fun too! And we’ll get back to “harder” topics quite soon. We are, however, still looking at how strong opinions can form around a topic, quite independently of any evidence that exists on the topic.

As software professionals, we should be interested in knowing at least the basics of our own history, for just the same reasons that as citizens we are expected to know about our national history and about world history: so that we will be able to make informed decisions and know who to trust, who to listen to; so that we are not deceived by lies. Untrue histories generally have an agenda - “someone trying to sell you something”, as the saying goes.

Quite a bit of the current debate on software engineering relies on opinions regarding the “creation myth” of the discipline: the so-called waterfall model of sequential software development, also known as the SDLC (Software Development Life Cycle).

Unfortunately, most of these opinions are wildly inaccurate.

The standard story

An article by Robert Martin provides (along with some other interpretations that I’ll come back to) what is now the nearly universal explanation of how conceptions of the SDLC became pervasive in the discourse of software engineering:

In 1970 a software engineer named Dr. Winston W. Royce wrote a seminal paper entitled Managing the Development of Large Software Systems. This paper described the software process that Royce felt was appropriate for large-scale systems. As a designer for the Aerospace industry, he was uniquely qualified. […] Royce’s paper was an instant hit. It was cited in many other papers, including several very important process documents in the early ’70s. One of the most influential of these was DOD2167, the document that described the software development process for the American Department of Defense. Royce was acclaimed, and became known as the father of the DOD process.

You can find further confirmation of the “seminal” character of Royce’s paper on Wikipedia:

The first formal description of the waterfall model is often cited as a 1970 article by Winston W. Royce, though Royce did not use the term “waterfall” in this article.

For many, the standard story is the whole story; over the ensuing decades, even though many variants on the “waterfall” life cycle were proposed that all have their uses in one context or another, the waterfall still remains one of the major foundations of software engineering. It’s the model to learn as a basis for learning other variants, and as such is taught quite seriously at many universities. It is a constant fallback of enterprise software development efforts, a norm against which other models are judged.

In any case, the following are widely, in fact almost universally, agreed upon:

- Dr. Winston Royce “invented” the waterfall model in 1970

- The nascent software engineering community welcomed the break from “artisanal” practice of the past

- The model was instantly enthusiastically adopted as a sequential, non-overlapping phases model

- Having become an industry norm, the model was taken up by the US DoD

- Variants of the model were developed later and used where appropriate

Alternate endings

There are at least two “modern” endings to the mythical story, told by different people according to whether they agree with the tenets of the Agile movement; for the Agilists,

- Tragically, this was all a misunderstanding, based on careless reading of Royce

- Royce was actually advocating an “iterative and incremental” approach in his paper (!)

Whereas for people who disagree with Agilists,

- “waterfall” is recent coinage and has been used only as a straw-man term

- formal lifecycles are not actually as inflexible and risky as “waterfall” is made out to be

- Royce’s paper wasn’t actually advocating a rigid sequential approach

The article by Robert Martin cited above is representative of the first group, which I’m tempted to characterize as “agile revisionists”; for instance he writes:

[Royce] began the paper by setting up a straw-man process to knock down. He described this naïve process as “grandiose”. He depicted it with a simple diagram on an early page of his paper. Then the paper methodically tears this “grandiose” process apart. […] Apparently the authors of DOD2167 did not actually read Royce’s paper; because they adopted the “grandiose”, naïve process that Royce’s paper had derided. To his great chagrin, Dr. Winston W. Royce became known as the father of the waterfall.

Larman and Basili, in their “Brief History” of iterative and incremental development, offer support this interpretation with a quote by Walker Royce - the son of Winston Royce: “He was always a proponent of iterative, incremental, evolutionary development.”

The second group is well represented by the following excerpts from a 2003 Web essay, titled “There’s no such thing as the Waterfall Approach (and there never was)”:

I don’t recall when I first saw that term, but I’m sure it was in a pejorative sense. I’m unaware of any article or paper that ever put forth the “waterfall methodology” as a positive or recommended approach to system development. In fact, “waterfall” is a straw-man term, coined and used by those trying to promote some new methodology by contrasting it with a silly alleged traditional approach that no competent methodology expert ever favored. […] Phase disciplines, when practiced with sensible judgment and flexibility, are a good thing with no offsetting downside. They are essential to the success of large projects. Bogus attacks on the non-existent “waterfall approach” can obscure a new methodology’s failure to support long-established sensible practice.

Just the facts

In fact, both modern interpretations are demonstrably wrong. Not only that - but all the elements of the standard myth turn out to be false or at least substantially at odds with the historical record.

First, what was Royce actually saying in that 1970 paper? Many who echo the “agile revisionist” quote a part of that paper where he says that the unmodified sequential approach “is risky and invites failure”.

However, as we all know, with selective quotation we can make anyone say anything we want. The full sentence was “I believe in this concept, but the implementation described above is risky and invites failure.” In other words, Royce is cautioning against simplistic interpretations, but not condemning the basic idea; a few paragraph further Royce adds this, which for some reason is much more rarely quoted:

I believe the illustrated approach to be fundamentally sound. The remainder of this discussion presents five additional features that must be added to this basic approach to eliminate most of the development risks.

From a close reading of Royce’s paper, “the illustrated approach” refers to Figure 3; that is, the picture showing a “cascading” series of activities, but allowing that iteration occurs between succeeding phases (the analysis phase may undergo rework on the basis of errors uncovered in the design phase, for instance; or the design may undergo rework as a result of errors in the coding phase). The “risky and invites failure” comment can be inferred, from its placement in the text, to refer to Figure 2 - which showed the same cascade of activities but no feedback loops at all.

Regarding the “five additional features”, again many people give in to the temptation to mention only one, that supports their reinterpretation of Royce: the recommendation to “Do It Twice”, i.e. flush out technical risk by building a prototype; and this is only #3 of the five. For completeness, the remaining four recommended features are:

- add what we would now call an “architecture phase” at the start of the process (#1)

- err on the side of too much documentation (#2)

- make sure to “plan, control and monitor” the testing process (#4)

- have the customer formally involved to sign off on various deliverables (#5)

Finally, Royce’s “iterative” recommendations stop short of allowing at any point that the first two “requirements” phases of the cycle can be included within an iterative loop: the “Do It Twice” recommendation is confined to the design and implementation stages.

No paper is an island

Anyone with an interest in so-called “development processes” should read the Royce paper carefully at least a couple times in their careers, but the really interesting part comes when we remember that in any discipline with an academic tradition, papers don’t exist in isolation.

Fortunately, with the help of today’s Web serious bibliographic research is within everyone’s reach. For instance, we can use Google Scholar to understand the real history of Royce’s paper within the larger context of the software engineering discipline. Scholar gives us in particular a list of the citations of Royce’s paper, which can be narrowed by date.

Did Royce’s 1970 paper “invent” or “formally define for the first time” the concept of the software development life cycle, or the notion of a succession of stages?

The answer is no: the first papers cited that mention (and draw a diagram of) a sequential or stagewise model of software development go back at least to 1956. The identification of Royce’s paper as the origin of the waterfall is largely arbitrary. Royce’s paper was however the origin of the most common picture of the waterfall - with its instantly recognizable downward cascade of boxes (and the loops showing iteration between phases, which some later authors omit). But as I’ll explain presently, that was probably not Royce’s fault at all - though it wasn’t due to careless reading either.

Was Royce’s paper “an instant hit”? The answer is no.

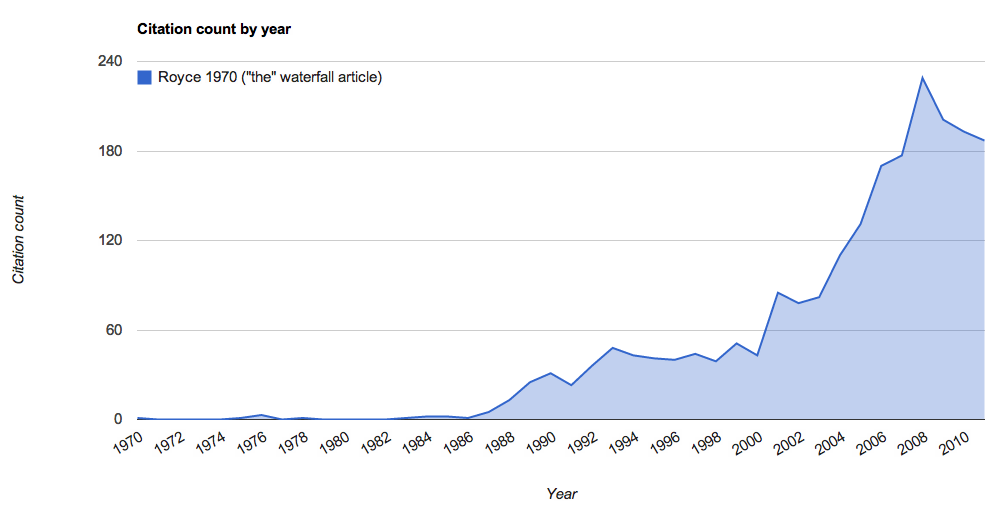

Taking a step back, let’s look at a graphical representation of how often Royce’s paper is cited in the software engineering literature:

We can see that the 1970 paper in fact remained almost totally unknown until 1987.

What the chart doesn’t show is a peculiar property of these early citations: just about every single one of them is by an author at TRW, a US defense contractor who employed several of the authors involved in the early years of the software engineering discipline, including Barry Boehm, known for an exceptional number of contributions to the field.

It turns out that Boehm (who cannot be accused of having read Royce “carelessly”) used Royce’s well-known diagram (Figure 3, the one with feedback loop between successive phases that Royce characterized as “fundamentally sound”) in a 1976 paper modestly titled “Software Engineering”.

In that paper, Boehm didn’t give credit to Royce for the picture (though he cites an unrelated paper of Royce’s). Rather, that diagram was used, with only the briefest of explanation, to provide a structure for the rest of the paper, which examined phase by phase the recent advances in software engineering. Several early authors in fact refer to the diagram as “Boehm’s waterfall”, rather than “Royce’s waterfall”.

Here is a quote from a paper by two of Boehm’s colleagues at TRW the same year:

The evolution of approaches for the development of software systems has generally paralleled the evolution of ideas for the implementation of code. Over the last ten years more structure and discipline have been adopted, and practicioners have concluded that a top-down approach is superior to the bottom-up approach of the past. The Military Standard set MIL-STD 490/483 recognized this newer approach […] The same top-down approach to a series of requirements statements is explained, without the specialized military jargon, in an excellent paper by Royce; he introduced the concept of the “waterfall” of development activities.

Rather than support the idea that Royce’s paper drew instant support and influenced military practice in software development, this quote suggests quite the opposite: the defense contractor TRW (who also had contacts within the US Defense departments responsible at the time for defining these standards) seems to have seized on Royce’s paper as a good introduction and justification of existing practice.

Late bloomer

Using Google Scholar to reconstruct the history of Royce’s paper, we can finally better understand how it ended up being known as “the origin of waterfall”.

Notice that there is a sudden surge of publications citing Royce’s paper in 1987: this is due to the paper having been republished in that year’s international software engineering conference, at the initiative of none other than Barry Boehm. Royce’s paper was published alongside two others that Boehm deemed of particular interest from a historical standpoint (one of the others was the 1956 paper which already defined a stagewise model).

(Another sudden surge of publications can be seen around 2001: the cause is harder to identify, because by then the myth is well established and the overall number of papers published each year that cite Royce is quite significant; but it is a safe bet that this renewed interest is due to the growing popularity of Agile at that time.)

There was a very good reason to call attention to the waterfall model at that time: Boehm had just introduced the (iterative) Spiral model of software development which would become one of his most significant publications. Boehm wrote in his 1987

Royce’s paper already incorporates prototyping as an essential step compatible with the waterfall model.

Birth of a myth

What I find particularly striking in this quote is the “compatible with”. Boehm seems to forget that if he takes Royce as the originator of waterfall then this prototyping step isn’t compatible with waterfall - it is waterfall. So, in effect, this quotation is kind of a smoking gun - it is the rhetorical moment where waterfall is being separated into two halves, one “stupid” waterfall and one “enlightened” reading. This later enlightened reading isn’t given the name waterfall, perhaps because to do so would diminish the import of Boehm’s own “Spiral” contribution.

In this sense, the interpretation of the waterfall as a “straw man” is not entirely false. But it isn’t accurate, either, to say that waterfall was always a straw man - for the first two decades, nearly, it was discussed generally quite favorably - if only within a relatively small circle of authors.

The story that the written record seems to tell is that the “Royce invented Waterfall” was a convenient myth. Convenient because people could satisfy the requirement of garnishing their papers with a citation, and because it provided a (relatively protean) straw man of “older, more primitive” processes that the more modern “iterative” processes could be contrasted with. And a myth whose career began seventeen years after original publication, breaking a long spell of obscurity but also beginning on the road to infamy.

I find this story, the true story of waterfall, much more interesting and enlightening than its caricatures.