The Making of a Fly

Although the e-commerce bubble burst dramatically at the turn of the century, bricks-and-mortar stores still had no real chance against those in the online world. Web shops can work around the clock, offer much more convenient access than physical stores, and reduce prices by automating away human staff. Just a decade after the dot-com boom and bust, traditional shops everywhere were being decimated by the web, closing their doors and firing staff. In 2013, Ashleigh Swan lost her job as a part-time shop assistant in Newcastle, UK. She was in her 20s with young children, and with no new job offers on the horizon, desperate to find ways to save money. Luckily, online shops made it easy to compare prices. Swan quickly learned that the high degree of automation in web stores has a flip side. With no humans involved, it’s a lot easier to make silly mistakes.

Swan started researching glitches in online supermarket prices, and casually shared the findings on her Facebook page. After publicising a £5 discount voucher from Asda that actually gave users £50 off, and a 1p dining table offer from Argos, she attracted the attention of mainstream media. At the time when I wrote this, in early 2017, Swan’s Facebook page had over half a million followers. She also built a website to share pricing errors and money-saving tips, which quickly attracted a large audience. It turned out that Swan didn’t need to look for another job. Advertising on the site brought in four times more money than her previous salary. I guess, technically, she’s still working as a shopping assistant, just for the other side.

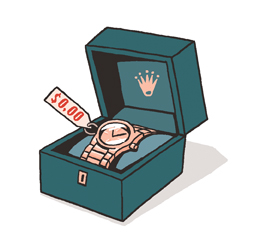

Pricing errors have surely existed since the first days of prehistoric trade, but they’re a lot easier to make online, because there are no people to spot obvious blunders during the checkout process. Even the early stars of e-commerce made silly mistakes. In January 2000, IBM offered ThinkPad i Series 1400 laptops for just $1, and received hundreds of orders in just an hour. During the 2001 Christmas season, Ashford.com offered designer watches at an amazing price of $0, with free shipping. Unsurprisingly, neither IBM nor Ashford honoured the price errors.

In the early 2000s, such problems would normally get spotted before shipping, when people finally got involved. However, when no physical products were being dispatched, nobody would know if computers were asleep at the wheel. In May 2002, United Airlines offered return flights from Denver to Chicago for just $5. In February that year, the airline also listed tickets for trips from the USA to Hong Kong, Paris and London for just $24.98, selling 143 tickets before the mistake was noticed. Once it had issued electronic tickets, United Airlines had to honour the transactions. But that didn’t stop the airline offering completely free tickets on 13 September 2013 (and yes, before you ask, it was a Friday). When the computer glitch causing $0 tickets was discovered, the company had to bring down the whole website and even stop taking orders over the phone.

As the entire process from shopping to delivery becomes increasingly automated, even hardware stores find it difficult to catch problems quickly. One day in 2014, at Screwfix.com, an online tools retailer, the price management system went into a loop. Instead of updating the price of a single item to £34.99, it fixed the cost of the entire inventory. Word quickly spread on Twitter, and orders started pouring in. Stephen Rand from Farndish, UK, was lucky enough to snatch a Mountfield 432cc ride-on tractor mower, which normally sold for £1600, and get it shipped before anyone noticed the problem. Once someone finally became aware of the mess, Screwfix took the whole website offline and tried stop any orders that had not yet left the warehouse.

The general trend with online stores is to blame the customers for errors and refuse to deliver wrongly priced items. However, when things really get out of hand, government agencies can step in. On 23 July 2010, Apple mistakenly offered a huge educational discount on its Mac Mini computers in Taiwan. Instead of the regular price of NT$47,710, local shoppers could buy the computer with almost 60% off, for just NT$19,900. And buy they did. Apple sold more than 41,000 units before spotting the error. At first, Apple decided to retroactively apply the full price to all the orders, but then had to deal with the Consumer Protection Commission, representatives from the Taipei City Government and the Ministry of Economic Affairs. A week later, the company agreed to deliver the computers to customers at the sale price. The agreement did, however, only apply to customers who were eligible for educational pricing. It’s difficult to calculate the full financial impact of the blunder, but estimates range from several million to tens of millions of US dollars.

Not all companies try to wiggle their way out of a pricing mistake, though. The online shoe retailer Zappos, famous for its great customer service, turned a costly error into some nice press. The entire inventory at 6pm.com, one of the Zappos sites, was updated to a single price at midnight on 23 May 2010. With an error oddly similar to the one at Screwfix, the site ran a fire sale, offering everything for just US$49.95 until people showed up for work. In a twist of irony, 6pm.com was fixed around 6am. By that time, Zappos had lost over US$1.6 million, but decided to honour all the late night shopping.

Another big area where the online world changed the retail industry is in being able to rent process automation from different providers easily. Small operators can combine distribution and logistics services, automate inventory management and even get items stored and dispatched by Amazon. This means that a single-person company can now offer products all over the world, without the capital expense of operating even a single warehouse. But like with other automation stories, when things go wrong, it’s almost impossible to stop the whole chain quickly.

Unlike IBM, Apple or even Screwfix, which at least had control of the things going out of their warehouses, Stephen Palmer from Aberfoyle in Scotland could only sit in despair and watch as his inventory was sold off for 1p. Palmer operated TV Village, selling TVs and mobile phones via Amazon Marketplace. To automatically adjust prices based on competing Marketplace products, he used Repricer Express, a service offering ‘the ridiculously simple way to increase your Amazon holiday sales’. On Friday 12 December 2014, Repricer Express had a brilliant idea to increase holiday sales, and set the price of everything to £0.01. Presumably Amazon wouldn’t let prices go any lower. The error was fixed within the hour, but the problem had already spiralled out of control due to the combination of Amazon’s amazing Christmas season delivery and the fact that the problem started just after normal working hours in the UK. Palmer got in touch with Amazon’s distribution centre the next day, but many shipments had already been dispatched, including one package for a single customer in Kent who’d ordered 59 mobile phones. Palmer’s wasn’t the only stock affected. Pretty much anything managed by Repricer Express was a huge bargain. According to the Guardian, Judith Blackford, owner of fancy dress company Kiddymania, lost about £20,000 overnight.

Unattended pricing algorithms are designed to automatically react to competitors, faster than people can. But in many cases, the algorithms are designed to outsmart people, not other computers. So, when two robots with similar objectives lock horns, you can count on a ton of misplaced assumptions causing problems. For a few days in 2011, a little known biology reference book was at the centre of an arms race between two pricing algorithms. The Making of a Fly, by Peter Lawrence, was published in 1992. By the time algorithms started paying attention to it, it had already been out of print for several years. No new supply meant that only second-hand books were available, and, with such an obscure title, it was difficult to determine the right price.

One seller, profnath, used an automated pricing algorithm to undercut other sellers without losing too much money. The algorithm adjusted the price to be the cheapest in Amazon Marketplace, but only by a few cents. And then, one day in April 2011, a seller called bordeebook got in on the game. As a high-volume Amazon seller with five-star ratings from lots of previous orders, bordeebook had a different pricing strategy. Its algorithms counted on people being willing to pay a slightly higher price for a book from a reputable merchant. In some cases, such companies don’t actually have all the items in the inventory, but count on buying from the cheapest seller in the market once someone places an order. So bordeebook automatically set the price to be a few dollars higher than the cheapest offer. Profnath’s algorithm noticed that it was underselling the book, and raised the price. Bordeebook’s algorithm noticed that it could no longer buy and dispatch the book at a profit, and raised its prices as well. And the game continued.

Both prices moved always by a few dollars, but because they were updated by robots, the situation quickly escalated. The two algorithms led a bidding war for days, ending up at the price of $23,698,655.93 (plus $3.99 for shipping). This price would make the biology textbook the second most expensive book in history, just behind Codex Leicester, a collection of Leonardo da Vinci’s original writing, which Bill Gates famously bought for $30.8 million in 1994. When a biology student actually wanted to buy the book, the story went viral, and fake reviews quickly started pouring in. One customer rated the book five stars, boasting that he’d picked it up when it cost ‘only 19 million’, but also complained that he had ‘expected more pictures for the price paid’.

Automated pricing algorithms are the future, there’s no doubt about that. Computers bid more competitively than people, and they can update prices much faster. But computers can also make mistakes much faster, and a complex algorithm can easily go into a self-reinforcing loop, especially when competing with another algorithm. It’s amazing that neither the profnath nor bordeebook system had a way to call out for help if things moved too much, too quickly.

It’s bad enough if two algorithms end up inciting each other, but, as the next story shows, a shouting match between several hundred algorithms can have a global impact.