The Three Guides of an Architect: Objectives, Principles & Outcomes

Desirable developer skills:

1 Ability to ignore new tools and technologies

2 Taste for simplicity

3 Good code deletion skills

4 Humility

By @codeinthehole on Twitter

Desirable architect skills:

1 Ability to ignore new tools and technologies

2 Taste for simplicity

3 Be Scientific with Objectives, Principles & Outcomes

4 Humility, please

By Russ

When you take on the responsibility of software architecture there is a lot of vague and blurry definitions of what you should be doing and thinking about. Is it about the “Big Decisions”, or mandating the usage of a particular framework or library in the service of “Consistency through Governance”? Maybe.

The problem is that those tasks can be very dependent on your context, and the values of your organisation. What would be helpful is an active, simple process for approaching and executing architectural work that was not context-specific but allowed you to tailor things to your own context.

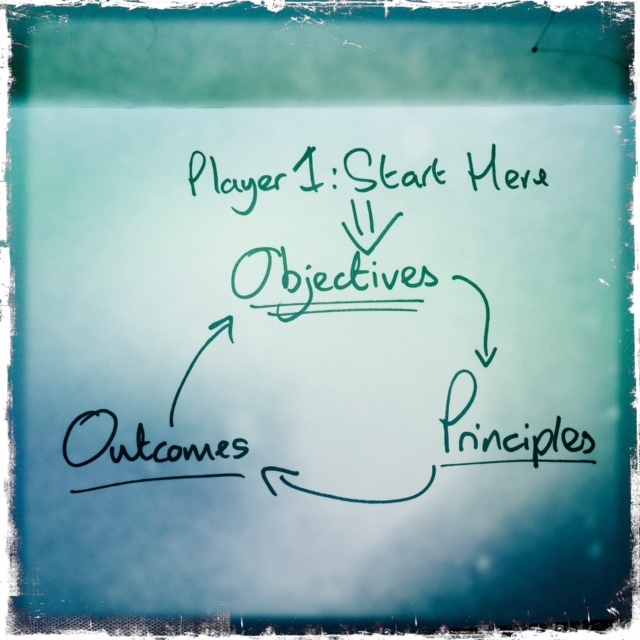

That process is what we gain by thinking in Objectives, Principles & Outcomes.

Why Objectives, Principles & Outcomes?

For me, this is the heart of what an ‘architect’ is thinking about, the triad of architectural thinking in software development:

The Software Architect’s Triad

Great architects in software development that I’ve known tend to think in this triad and work an iterative process around the details in each of the waypoints.

Also I was particular inspired by a talk given by Adrian Cockroft of, at the time, Netflix. Adrian explained how he, as Cloud Architect, would go about capturing the overall organisations goals, how that could be communicated and enforced through principles, and how he could then look for and adjust for resulting outcomes.

It was such a neat, pragmatic, and even empirically scientific explanation of the process of architectural guidance that I couldn’t help but follow Picasso’s advice and ‘steal’ from Adrian to set the structure for this guidebook.

Dangers of “Vacuum Thinking”

There is a very real danger when writing any book on software architecture of ending up writing “from the rarified air of the unreal mountaintop”. Many books, and speakers, fall foul of this one. The problem is that as a set of ideas is made more generically applicable, you lose the context entirely and in fact completely dilute the meaning and power of what you’re trying to put across.

Software architecture is probably the easiest place in software to fall make this mistake.

“Context is King” is my own mantra as a software consultant and developer, and I’d certainly advice my readers to consider this too. The other mantra I have is “We don’t know what we’re doing”, but dealing with that is reserved for a different book (Antifragile Software). With all of these mantras, I speak to myself a lot … that’s possibly not a good thing but there you go!

The point here is that all of the sections of this book should be broken out of the rarified, vacuum-like surrounds of these pages and carefully assessed as to their important to your given specific context. As always, there are no general silver bullets, so apply what you learn about here with care of your context. Be scientific…

Iterative, and Scientific

The job of the modern software architect, first and foremost, is to be scientific about things. To do that you need to have the triad on a in a continuous-replay, feedback loop:

TBD Diagram of three things.

As architects we are responsible for setting principles within the scope of desirable, hypothetical objectives, and then to measure the outcomes and relate those back to the objectives. Constantly, iteratively, refining as we go.

Taking the scientific process, this is how things map across:

TBD Diagram of how hypothesis, method and findings map to triad.

Providing the momentum in this empirical, practical process is the main part of the modern software architect’s responsibility.

Communication, communication, communication

In order to turn principles into any measurable outcomes, we need to communicate them.

Anyone taking on the responsibility of thinking about the software architecture is therefore going to need to be able to get out there and communicate those principles that are forming the outcomes that are to be compared against the general and specific objectives of your organisation.

Empower, and Lightly Enforce

Communication can only go so far… Sometimes you need something more active to attempt to make sure that those principles you’ve selected are being understood applied, otherwise misapplication of principles could completely kill the validity of any outcomes that you measure.

Luckily we have tests and monkeys. I am of course referring to the example of the Simian Army (TBD link) in the latter, not raiding the local zoo.

One of the key jobs of the architect responsibility is to come up with active participants that stress the resulting designs and implementations of the software, looking for deviations from the principles that are being applied.

These stressors, a force on a system that provides an opportunity for the system to gain from that force, at design, build and operational times can come in many flavours. I have had most success with is by applying development and build-time tests and operational stressors from my own army of simians to show that the system exhibits the ability to deal with these stressors that imply strongly that the principles are being followed.

Also, to be honest, it’s fun to create software that breaks software when it doesn’t follow a given principle, or maybe that speaks to my own sadistic tendencies … the serious point is that this turns architectural principles into something actively applied and enforced, which is of huge benefit when assessing the outcomes of our architectural experiments.

Let’s get started

It’s not time to begin your journey towards adopting the Empirical Architect responsibilities by looking first at some candidate general objectives.