Chapter 1: Safety

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Item 1: Limit mutability

In Kotlin, we design programs in modules, each of which comprises different kinds of elements, such as classes, objects, functions, type aliases, and top-level properties. Some of these elements can hold a state, for instance, by having a read-write var property or by composing a mutable object:

var a = 10

val list: MutableList<Int> = mutableListOf()

When an element holds a state, the way it behaves depends not only on how you use it but also on its history. A typical example of a class with a state is a bank account (class) that has some money balance (state):

class BankAccount {

var balance = 0.0

private set

fun deposit(depositAmount: Double) {

balance += depositAmount

}

@Throws(InsufficientFunds::class)

fun withdraw(withdrawAmount: Double) {

if (balance < withdrawAmount) {

throw InsufficientFunds()

}

balance -= withdrawAmount

}

}

class InsufficientFunds : Exception()

val account = BankAccount()

println(account.balance) // 0.0

account.deposit(100.0)

println(account.balance) // 100.0

account.withdraw(50.0)

println(account.balance) // 50.0

Here BankAccount has a state that represents how much money is in this account. Keeping a state is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it is very useful because it makes it possible to represent elements that change over time. On the other hand, state management is hard because:

- It is harder to understand and debug a program with many mutating points. The relationship between these mutations needs to be understood, and it is harder to track how they have changed when more of them occur. A class with many mutating points that depend on each other is often really hard to understand and modify. This is especially problematic in the case of unexpected situations or errors.

- Mutability makes it harder to reason about code. The state of an immutable element is clear, but a mutable state is much harder to comprehend. It is harder to reason about what its value is as it might change at any point; therefore, even though we might have checked a moment ago, it might have already changed.

- A mutable state requires proper synchronization in multithreaded programs. Every mutation is a potential conflict. We will discuss this in more detail later in the next item. For now, let’s just say that it is hard to manage a shared state.

- Mutable elements are harder to test. We need to test every possible state; the more mutability there is, the more states there are to check. Moreover, the number of states we need to test generally grows exponentially with the number of mutation points in the same object or file, as we need to consider all combinations of possible states.

- When a state mutates, other classes often need to be notified about this change. For instance, when we add a mutable element to a sorted list, if this element changes, we need to sort this list again.

The drawbacks of mutability are so numerous that there are languages that do not allow state mutation at all. These are purely functional languages, a well-known example of which is Haskell. However, such languages are rarely used for mainstream development since it’s very hard to do programming with such limited mutability. A mutating state is a very useful way to represent the state of real-world systems. I recommend using mutability, but only where it gives us some real value. When possible, it is better to limit it. The good news is that Kotlin has good support for limiting mutability.

Limiting mutability in Kotlin

Kotlin is designed to support limiting mutability: it is easy to make immutable objects or to keep properties immutable. This is a result of many features and characteristics of this language, the most important of which are:

- Read-only properties

val, - Separation between mutable and read-only collections,

-

copyin data classes.

Let’s discuss these one by one.

Read-only properties

In Kotlin, we can make each property a read-only val (like “value”) or a read-write var (like “variable”). Read-only (val) properties cannot be set to a new value:

val a = 10

a = 20 // ERROR

Notice though that read-only properties are not necessarily immutable or final. A read-only property can hold a mutable object:

val list = mutableListOf(1, 2, 3)

list.add(4)

print(list) // [1, 2, 3, 4]

A read-only property can also be defined using a custom getter that might depend on another property:

var name: String = "Marcin"

var surname: String = "Moskała"

val fullName

get() = "$name $surname"

fun main() {

println(fullName) // Marcin Moskała

name = "Maja"

println(fullName) // Maja Moskała

}

In the above example, the value returned by the val changes because when we define a custom getter, it will be called every time we ask for the value.

fun calculate(): Int {

print("Calculating... ")

return 42

}

val fizz = calculate() // Calculating...

val buzz

get() = calculate()

fun main() {

print(fizz) // 42

print(fizz) // 42

print(buzz) // Calculating... 42

print(buzz) // Calculating... 42

}

This trait, namely that properties in Kotlin are encapsulated by default and can have custom accessors (getters and setters), is very important in Kotlin because it gives us flexibility when we change or define an API. This will be described in detail in Item 15: Properties should represent state, not behavior. The core idea though is that val does not offer mutation points because, under the hood, it is only a getter. var is both a getter and a setter. That’s why we can override val with var:

interface Element {

val active: Boolean

}

class ActualElement : Element {

override var active: Boolean = false

}

Values of read-only val properties can change, but such properties do not offer a mutation point, and this is the main source of problems when we need to synchronize or reason about a program. This is why we generally prefer val over var.

Remember that val doesn’t mean immutable. It can be defined by a getter or a delegate. This fact gives us more freedom to change a final property into a property represented by a getter. However, when we don’t need to use anything more complicated, we should define final properties, which are easier to reason about as their value is stated next to their definition. They are also better supported in Kotlin. For instance, they can be smart-casted:

val name: String? = "Márton"

val surname: String = "Braun"

val fullName: String?

get() = name?.let { "$it $surname" }

val fullName2: String? = name?.let { "$it $surname" }

fun main() {

if (fullName != null) {

println(fullName.length) // ERROR

}

if (fullName2 != null) {

println(fullName2.length) // 12

}

}

Smart casting is impossible for fullName because it is defined using a getter; so, when checked it might give a different value than it does during use (for instance, if some other thread sets name). Non-local properties can be smart-casted only when they are final and do not have a custom getter.

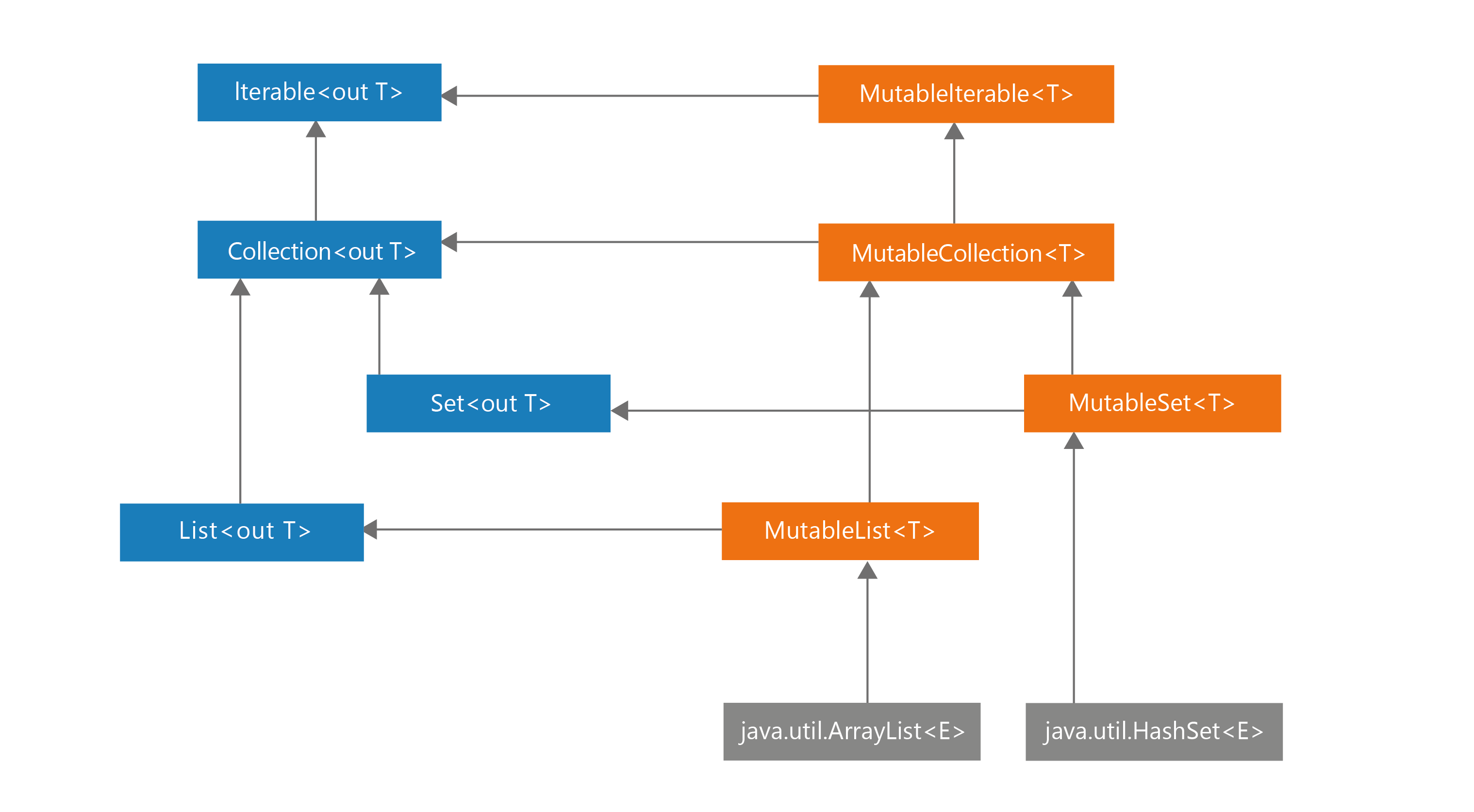

Separation between mutable and read-only collections

Similarly, just as Kotlin separates read-write and read-only properties, Kotlin also separates read-write and read-only collections. This is achieved thanks to how the hierarchy of collections was designed. Take a look at the diagram presenting the hierarchy of collections in Kotlin. On the left side, you can see the Iterable, Collection, Set, and List interfaces, all of which are read-only. This means that they do not have any methods that would allow modification. On the right side, you can see the MutableIterable, MutableCollection, MutableSet, and MutableList interfaces, all of which represent mutable collections. Notice that each mutable interface extends the corresponding read-only interface and adds methods that allow mutation. This is similar to how properties work. A read-only property means just a getter, while a read-write property means both a getter and a setter.

Read-only collections are not necessarily immutable. They are often mutable, but they cannot be mutated because they are hidden behind read-only interfaces. For instance, the Iterable<T>.map and Iterable<T>.filter functions return ArrayList (which is a mutable list) as a List, which is a read-only interface. In the snippet below, you can see a simplified implementation of Iterable<T>.map from stdlib.

inline fun <T, R> Iterable<T>.map(

transformation: (T) -> R

): List<R> {

val list = ArrayList<R>()

for (elem in this) {

list.add(transformation(elem))

}

return list

}

The design choice to make these collection interfaces read-only instead of truly immutable is very important because it gives us much more freedom. Under the hood, any actual collection can be returned as long as it satisfies the interface; therefore, we can use platform-specific collections.

The safety of this approach is close to what is achieved by having immutable collections. The only risk is when a developer tries to “hack the system” by performing down-casting. This is something that should never be allowed in Kotlin projects. We should be able to trust that when we return a list as read-only, it is only used to read it. This is part of the contract. More about this in Part 2.

Down-casting collections not only breaks their contract and depends on implementation instead of abstraction (as we should), but it is also insecure and can lead to surprising consequences. Take a look at this code:

val list = listOf(1, 2, 3)

// DON’T DO THIS!

if (list is MutableList) {

list.add(4)

}

The result of this operation depends on our compilation target. On JVM, listOf returns an instance of Arrays.ArrayList that implements the Java List interface, which has methods like add and set, so it translates to the Kotlin MutableList interface. However, Arrays.ArrayList does not implement add and some other operations that mutate objects. This is why the result of this code is UnsupportedOperationException. On different platforms, the same code could give us different results.

What is more, there is no guarantee how this will behave a year from now. The underlying collections might change; they might be replaced with truly immutable collections implemented in Kotlin that do not implement MutableList at all. Nothing is guaranteed. This is why down-casting read-only collections to mutable ones should never happen in Kotlin. If you need to transform from read-only to mutable, you should use the List.toMutableList function, which creates a copy that you can then modify:

val list = listOf(1, 2, 3)

val mutableList = list.toMutableList()

mutableList.add(4)

This way does not break any contract, and it is safer for us as we can feel safe that when we expose something as List it won’t be modified from outside.

Copy in data classes

There are many reasons to prefer immutable objects – objects that do not change their internal state, like String or Int. In addition to the previously given reasons why we generally prefer less mutability, immutable objects have their own advantages:

- They are easier to reason about since their state stays the same once they have been created.

- Immutability makes it easier to parallelize a program as there are no conflicts among shared objects.

- References to immutable objects can be cached as they will not change.

- We do not need to make defensive copies of immutable objects. When we do copy immutable objects, we do not need to make a deep copy.

- Immutable objects are the perfect material to construct other objects, both mutable and immutable. We can still decide where mutability is allowed, and it is easier to operate on immutable objects.

- We can add them to sets or use them as keys in maps, unlike mutable objects, which shouldn’t be used this way. This is because both these collections use hash tables under the hood in Kotlin/JVM. When we modify an element that is already classified in a hash table, its classification might not be correct anymore, therefore we won’t be able to find it. This problem will be described in detail in Item 43: Respect the contract of hashCode. We have a similar issue when a collection is sorted.

val names: SortedSet<FullName> = TreeSet()

val person = FullName("AAA", "AAA")

names.add(person)

names.add(FullName("Jordan", "Hansen"))

names.add(FullName("David", "Blanc"))

print(s) // [AAA AAA, David Blanc, Jordan Hansen]

print(person in names) // true

person.name = "ZZZ"

print(names) // [ZZZ AAA, David Blanc, Jordan Hansen]

print(person in names) // false

At the last check, the collection returned false even though that person is in this set. It couldn’t be found because it is at an incorrect position.

As you can see, mutable objects are more dangerous and less predictable. On the other hand, the biggest problem of immutable objects is that data sometimes needs to change. The solution is that immutable objects should have methods that produce a copy of this object with the desired changes applied. For instance, Int is immutable, and it has many methods like plus or minus that do not modify it but instead return a new Int, which is the result of the operation. Iterable is read-only, and collection processing functions like map or filter do not modify it but instead return a new collection. The same can be applied to our immutable objects. For instance, let’s say that we have an immutable class User, and we need to allow its surname to change. We can support it with the withSurname method, which produces a copy with a particular property changed:

class User(

val name: String,

val surname: String

) {

fun withSurname(surname: String) = User(name, surname)

}

var user = User("Maja", "Markiewicz")

user = user.withSurname("Moskała")

print(user) // User(name=Maja, surname=Moskała)

Writing such functions is possible but it’s also tedious if we need one for every property. So, here comes the data modifier to the rescue. One of the methods it generates is copy. The method copy creates a new instance in which all primary constructor properties are, by default, the same as in the previous one. New values can be specified as well. copy and other methods generated by the data modifier are described in detail in Item 37: Use the data modifier to represent a bundle of data. Here is a simple example showing how it works:

data class User(

val name: String,

val surname: String

)

var user = User("Maja", "Markiewicz")

user = user.copy(surname = "Moskała")

print(user) // User(name=Maja, surname=Moskała)

This elegant and universal solution supports making data model classes immutable. This way is less efficient than just using a mutable object instead, but it is safer and has all the other advantages of immutable objects. Therefore it should be preferred by default.

Different kinds of mutation points

Let’s say that we need to represent a mutating list. There are two ways we can achieve this: either by using a mutable collection or by using the read-write var property:

val list1: MutableList<Int> = mutableListOf()

var list2: List<Int> = listOf()

Both properties can be modified, but in different ways:

list1.add(1)

list2 = list2 + 1

Both of these ways can be replaced with the plus-assign operator, but each of them is translated into a different behavior:

list1 += 1 // Translates to list1.plusAssign(1)

list2 += 1 // Translates to list2 = list2.plus(1)

Both these ways are correct, and both have their pros and cons. They both have a single mutating point, but each is located in a different place. In the first one, the mutation takes place on the concrete list implementation. We might depend on the fact that the collection has proper synchronization in the case of multithreading, if we used a collection with support for concurrency1. In the second one, we need to implement the synchronization ourselves, but the overall safety is better because the mutating point is only a single property. However, in the case of a lack of synchronization, remember that we might still lose some elements:

var list = listOf<Int>()

for (i in 1..1000) {

thread {

list = list + i

}

}

Thread.sleep(1000)

print(list.size) // Very unlikely to be 1000,

// every time a different number, like for instance 911

Using a mutable property instead of a mutable list allows us to track how this property changes when we define a custom setter or use a delegate (which uses a custom setter). For instance, when we use an observable delegate, we can log every change of a list:

var names by observable(listOf<String>()) { _, old, new ->

println("Names changed from $old to $new")

}

names += "Fabio"

// Names changed from [] to [Fabio]

names += "Bill"

// Names changed from [Fabio] to [Fabio, Bill]

To make this possible for a mutable collection, we would need a special observable implementation of the collection. For read-only collections in mutable properties, it is also easier to control how they change as there is only a setter instead of multiple methods mutating this object, and we can make it private:

var announcements = listOf<Announcement>()

private set

In short, using mutable collections is a slightly faster option, but using a mutable property instead gives us more control over how the object changes.

Notice that the worst solution is to have both a mutating property and a mutable collection:

// Don’t do that

var list3 = mutableListOf<Int>()

The general rule is that one should not create unnecessary ways to mutate a state. Every way to mutate a state is a cost. Every mutation point needs to be understood and maintained. We prefer to limit mutability.

Summary

In this chapter, we’ve learned why it is important to limit mutability and to prefer immutable objects. We’ve seen that Kotlin gives us many tools that support limiting mutability. We should use them to limit mutation points. The simple rules are:

- Prefer

valovervar. - Prefer an immutable property over a mutable one.

- Prefer objects and classes that are immutable over mutable ones.

- If you need immutable objects to change, consider making them data classes and using

copy. - When you hold a state, prefer read-only over mutable collections.

- Design your mutation points wisely and do not produce unnecessary ones.

There are some exceptions to these rules. Sometimes we prefer mutable objects because they are more efficient. Such optimizations should be preferred only in performance-critical parts of our code (Part 3: Efficiency); when we use them, we need to remember that mutability requires more attention when we prepare it for multithreading. The baseline is that we should limit mutability.

Item 2: Eliminate critical sections

When multiple threads modify a shared state, it can lead to unexpected results. This problem was already discussed in the previous item, but now I want to explain it in more detail and show how to deal with it in Kotlin/JVM.

The problem with threads and shared state

While I’m writing these words, many things are happening concurrently on my computer. Music is playing, IntelliJ displays the text of this chapter, Slack is displaying messages, and my browser is downloading data. All this is possible because operating systems introduced the concept of threads. The operating system schedules the execution of threads, each of which is a separate flow. Even if I had a single-core CPU, the operating system would still be able to run multiple threads concurrently by running one thread for a short period of time, then switching to another thread, and so on. This is called time slicing. What is more, in modern computers we have multiple cores, so operating systems can actually run many operations on different threads at the same time.

The biggest problem with this process is that we cannot be sure when the operating system will switch from executing one thread to executing another. Consider the following example. We start 1000 threads, each of which increments a mutable variable; the problem is that incrementing a value has multiple steps: getting the current value, creating the new incremented value, and assigning it to the variable. If the operating system switches threads between these steps, we might lose some increments. This is why the code below is unlikely to print 1000. I just tested it, and it printed 981.

var num = 0

for (i in 1..1000) {

thread {

Thread.sleep(10)

num += 1

}

}

Thread.sleep(5000)

print(num) // Very unlikely to be 1000

// Every time a different number

To better understand this problem, just consider the following situation that might occur if we had started two threads. One thread gets value 0, then the CPU switches execution to the other thread, which gets the same value, increments it, and sets the variable to 1. The operating system switches to the previous thread, which then sets the variable to 1 again. In this case, we’ve lost one incrementation.

Losing some operations can be a serious problem in real-life applications, but this problem can have much more serious consequences. When we don’t know the order in which operations will be executed, we risk our objects having incorrect states. This often leads to bugs that are hard to reproduce and fix, as is well visualized by adding an element to a list while another thread iterates over its elements. The default collections do not support their elements being modified when they are iterated over, so we get a ConcurrentModificationException exception.

var numbers = mutableListOf<Int>()

for (i in 1..1000) {

thread {

Thread.sleep(1)

numbers.add(i)

}

thread {

Thread.sleep(1)

print(numbers.sum()) // sum iterates over the list

// often ConcurrentModificationException

}

}

We encounter the same problem when we start multiple coroutines on a dispatcher that uses multiple threads. To deal with this problem when using coroutines, we can use the same techniques as for threads. However, coroutines also have dedicated tools, as I described in detail in the book Kotlin Coroutines: Deep Dive.

As I explained in the previous chapter, we don’t encounter all these problems if we don’t use mutability. However, in real-life applications we often cannot avoid mutability, so we need to learn how to deal with shared state2. Whenever you have a shared state that might be modified by multiple threads, you need to ensure that all the operations on this state are executed correctly. Each platform offers different tools for this, so let’s learn about the most important tools for Kotlin/JVM3.

Synchronization in Kotlin/JVM

The most important tool for dealing with shared state in the Kotlin/JVM platform is synchronization. This is a mechanism that allows us to ensure that only one thread can execute a given block of code at the same time. It is based on the synchronized function, which requires a lock object and a lambda expression with the code that should be synchronized. This mechanism guarantees that only one thread can enter a synchronization block with the same lock at the same time. If a thread reaches a synchronization block but a different thread is already executing a synchronization block with the same lock, this thread will wait until the other thread finishes its execution. The following example shows how to use synchronization to ensure that the num variable is incremented correctly.

val lock = Any()

var num = 0

for (i in 1..1000) {

thread {

Thread.sleep(10)

synchronized(lock) {

num += 1

}

}

}

Thread.sleep(1000)

print(num) // 1000

In real-life cases, we often wrap all the functions in a class that need to be synchronized with a synchronization block. The example below shows how to synchronize all the operations in the Counter class.

class Counter {

private val lock = Any()

private var num = 0

fun inc() = synchronized(lock) {

num += 1

}

fun dec() = synchronized(lock) {

num -= 1

}

// Synchronization is not necessary; however,

// without it, getter might serve stale value

fun get(): Int = num

}

In some classes, we have multiple locks for different parts of a state, but this is much harder to implement correctly, so it’s much less common.

When we use Kotlin Coroutines, instead of using

synchronized, we rather use a dispatcher limited to a single thread orMutex, as I described that in the book Kotlin Coroutines: Deep Dive. Remember that thread-switching is not free, and in some classes it is more efficient to use a single thread instead of using multiple threads and synchronizing their execution.

Atomic objects

We started our discussion with the problem of incrementing a variable, which can produce incorrect results because regular integer incrementation has multiple steps, but the operating system can switch between threads in the middle of these. Some operations, such as a simple value assignment, are only a single processor step, so they are always executed correctly, but only very simple operations are atomic by nature. However, Java provides a set of atomic classes that represent popular Java classes but with atomic operations. You can find AtomicInteger, AtomicLong, AtomicBoolean, AtomicReference, and many more. Each of these offers methods that are guaranteed to be executed atomically. For example, AtomicInteger offers an incrementAndGet method that increments a value and returns the new value. The example below shows how to use AtomicInteger to increment a variable correctly.

val num = AtomicInteger(0)

for (i in 1..1000) {

thread {

Thread.sleep(10)

num.incrementAndGet()

}

}

Thread.sleep(5000)

print(num.get()) // 1000

Atomic objects are fast and can help us with simple cases where a state is a simple value or a couple of independent values, but these are not enough for more complex cases. For example, we cannot use atomic objects to synchronize multiple operations on multiple objects. For that, we need to use a synchronization block.

Concurrent collections

Java also provides some collections that have support for concurrency. The most important one is ConcurrentHashMap, which is a thread-safe version of HashMap. We can safely use all its operations without worrying about conflicts. When we iterate over it, we get a snapshot of the state at the moment of iteration, therefore we’ll never get a ConcurrentModificationException exception, but this doesn’t mean that we’ll get the most recent state.

val map = ConcurrentHashMap<Int, String>()

for (i in 1..1000) {

thread {

Thread.sleep(1)

map.put(i, "E$i")

}

thread {

Thread.sleep(1)

print(map.toList().sumOf { it.first })

}

}

When we need a concurrent set, a popular choice is to use newKeySet from ConcurrentHashMap, which is a wrapper over ConcurrentHashMap that uses Unit as a value. It implements the MutableSet interface, so we can use it like a regular set.

val set = ConcurrentHashMap.newKeySet<Int>()

for (i in 1..1000) {

thread {

Thread.sleep(1)

set += i

}

}

Thread.sleep(5000)

println(set.size)

Instead of lists, I typically use ConcurrentLinkedQueue when I need a concurrent collection that allows duplicates. These are the essential tools that we can use on JVM to deal with the problem of mutable states.

Of course, there are also libraries that offer other tools that support code synchronization. There are even Kotlin multiplatform libraries, such as AtomicFU, which provides multiplatform atomic objects4.

// Using AtomicFU

val num = atomic(0)

for (i in 1..1000) {

thread {

Thread.sleep(10)

num.incrementAndGet()

}

}

Thread.sleep(5000)

print(num.value) // 1000

Let’s change our perspective back to the more general problem with mutable states and explain how to deal with it in typical situations.

Do not leak mutation points

Exposing a mutable object that is used to represent a public state, like in the following examples, is an especially dangerous situation. Take a look at this example:

data class User(val name: String)

class UserRepository {

private val users: MutableList<User> = mutableListOf()

fun loadAll(): MutableList<User> = users

//...

}

One could use loadAll to modify the UserRepository private state:

val userRepository = UserRepository()

val users = userRepository.loadAll()

users.add(User("Kirill"))

//...

print(userRepository.loadAll()) // [User(name=Kirill)]

This situation is especially dangerous when such modifications are accidental. The first thing we should do is upcast the mutable objects to read-only types; in this case it means upcasting from MutableList to List.

data class User(val name: String)

class UserRepository {

private val users: MutableList<User> = mutableListOf()

fun loadAll(): List<User> = users

//...

}

But beware, because the implementation above is not enough to make this class safe. First, we receive what looks like a read-only list, but it is actually a reference to a mutable list, so its values might change. This might cause developers to make serious mistakes:

data class User(val name: String)

class UserRepository {

private val users: MutableList<User> = mutableListOf()

fun loadAll(): List<User> = users

fun add(user: User) {

users += user

}

}

class UserRepositoryTest {

fun `should add elements`() {

val repo = UserRepository()

val oldElements = repo.loadAll()

repo.add(User("B"))

val newElements = repo.loadAll()

assert(oldElements != newElements)

// This assertion will fail, because both references

// point to the same object, and they are equal

}

}

Second, consider a situation in which one thread reads the list returned using loadAll, but another thread modifies it at the same time. It is illegal to modify a mutable collection that another thread is iterating over. Such an operation leads to an unexpected exception.

val repo = UserRepository()

thread {

for (i in 1..10000) repo.add(User("User$i"))

}

thread {

for (i in 1..10000) {

val list = repo.loadAll()

for (e in list) {

/* no-op */

}

}

}

// ConcurrentModificationException

There are two ways of dealing with this. The first is to return a copy of an object instead of a real reference. We call this technique defensive copying. Note that when we copy, we might have a conflict if another thread is adding a new element to the list while we are copying it; so, if we want to support multithreaded access to our object, this operation needs to be synchronized. Collections can be copied with transformation functions like toList, while data classes can be copied with the copy method.

class UserRepository {

private val users: MutableList<User> = mutableListOf()

private val lock = Any()

fun loadAll(): List<User> = synchronized(lock) {

users.toList()

}

fun add(user: User) = synchronized(lock) {

users += user

}

}

A simpler option is to use a read-only list as this is easier to secure and gives us more ways of tracking changes in objects.

class UserRepository {

private var users: List<User> = listOf()

fun loadAll(): List<User> = users

fun add(user: User) {

users = users + user

}

}

When we use this option, and we want to introduce proper support for multithreaded access, we only need to synchronize the operations that modify our list. This makes adding elements slower, but accessing the list is faster. This is a good trade-off when we have more reads than writes.

class UserRepository {

private var users: List<User> = listOf()

private val lock = Any()

fun loadAll(): List<User> = users

fun add(user: User) = synchronized(lock) {

users = users + user

}

}

Summary

- Multiple threads modifying the same state can lead to conflicts, thus causing lost data, exceptions, and other unexpected behavior.

- We can use synchronization to protect a state from concurrent modifications. The most popular tool in Kotlin/JVM is a

synchronizedblock with a lock. - To deal with concurrent modifications, Java also provides classes to represent atomic values and concurrent collections.

- There are also libraries that provide multiplatform atomic objects, such as AtomicFU.

- Classes should protect their internal state and not expose it to the outside world. We can operate on read-only objects or use defensive copying to protect a state from concurrent modifications.

Item 3: Eliminate platform types as soon as possible

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Summary

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Item 4: Minimize the scope of variables

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Capturing

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Summary

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Item 5: Specify your expectations for arguments and state

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Arguments

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

State

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Nullability and smart casting

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

The problems with the non-null assertion !!

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Using Elvis operator

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

error function

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Summary

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Item 6: Prefer standard errors to custom ones

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Item 7: Prefer a nullable or Result result type when the lack of a result is possible

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Using Result result type

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Using null result type

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Null is our friend, not an enemy

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Defensive and offensive programming

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Summary

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Item 8: Close resources with use

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Summary

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Item 9: Write unit tests

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.

Summary

This content is not available in the sample book. The book can be purchased on Leanpub at http://leanpub.com/effectivekotlin.