3: Make yourself comfortable

There’s no way you can work well in a new skill if you aren’t comfortable with it, and dowsing is no exception. And there are two sides to that ‘comfortable’ feeling: not just being comfortable with the tools you use, but also comfortable in yourself, being confident in what you’re doing.

To my mind, most of what we need to learn in dowsing falls into the latter category: it’s mainly about interpretation, about what we perceive from the information we receive. That’s why dowsing is such an interesting skill, because so much of it depends on you, on who you are – so much so that you can use it as a mirror of how well you understand yourself.

But there is a physical aspect to this, and that’s to do with the tools we use to amplify the wrist muscles’ dowsing response. Quite small physical changes can make a big difference in how well, and how quickly, angle rods respond to a given wrist movement. So by making pairs of rods in different ways and out of different weights and sizes and types of material, we can explore a variety of subtle if solely mechanical effects on what feels comfortable, on what feels ‘right’ in a dowsing instrument.

3.1 Variations on a theme

Your angle rods are levers using neutral balance as the mechanical principle to amplify your wrist movements. Everything depends on that balance, and the freedom to move that’s implied by a neutral balance, neither stable nor unstable.

We looked at some of this in Exercise 4, where we saw the effect that your wrist angle had on how much the rods moved and how easy – or not – it was to keep them stable. The joint-angle of the angle rod itself – between the short and long arms – has a similar effect. To begin with, as in the last chapter, a merely approximate right-angle is quite good enough, but it is worthwhile experimenting with it to find the angle that’s most comfortable for you:

Another very simple change to try is to turn the rods upside- down:

Some people also like to use handles, so that the rods can turn more easily; others prefer to feel the movement of the shaft of the rod directly against the skin of their fingers. Find out which approach works best for you:

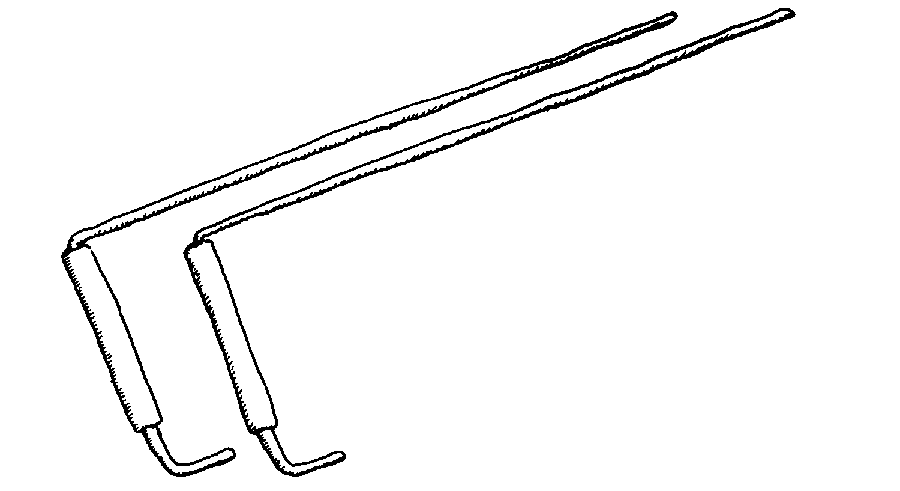

You’ll probably have found that using handles does make a lot of difference: it makes the rods far more mobile but also, in a way, less tangible, less certain; and the wrist-angle and, especially, the joint-angle, become far more critical in their effects on the rods’ rate of response. In general, if I’m using a rod made of some relatively lightweight material such as a coat-hanger, I prefer to do without handles; but if I’m using some heavier material such as the 3/16” mild steel rod used in my favourite commercially-made pair (see Fig. 3.1), the handles are almost essential, and do give me a sense of certainty about the response. But that’s my choice: what works well for you is what works well for you, not necessarily what works well for me!

Figure 3.1: Commercial rods with handles

The actual material we use for angle rods can make a lot of difference to how well they work for you, partly for good physical reasons, and partly from a more indefinable sense of what does and does not feel right. So it’s worthwhile experimenting by making sets of rods from different materials and in different ways – variations on a theme of angle rods – to see what effects they have in what works well and what doesn’t work so well.

For this group of experiments you’ll need a better supply of rod-material than coat-hangers, or you won’t have anything left to hang your clothes on! Two alternatives that should work well and don’t cost much are welding or brazing rod, or stiff single- core electrical wire such as earthing cable – both of which you should find at your local builders’ supplies store.

You’ll certainly have noticed a difference there: the response will have been much more twitchy and unstable than with the arms the other, more usual way round. (If it didn’t move at all, you were holding the shaft too tightly, so that the smaller inertia couldn’t break the starting friction of your grip. If that’s the case, relax a little!) In some circumstances, though, it’s useful to have it be less stable – you get a faster response – and the shorter length of rod is less likely to get tangled up with the wall as you walk around…

Let’s continue that theme a little further, and try out the effects of a whole sequence of different lengths:

Changing the length of the rod changes both the centre of mass of the rod – and thus its response time – and the overall weight. One side-effect of changing the overall weight is that the inertia also changes: if you reduce it too far, the rod becomes more and more susceptible to being pushed around by the wind and similar interferences. One way of moving the centre of mass without changing the overall inertia is to mount a small weight, such as a lump of modelling clay, onto the rod, and move that to various positions on the rod. The further away from the axis (your fist, in other words) that you move the weight, the further out goes the centre of mass, and the more-smooth but slower- reacting becomes the rods’ response. Try it:

The effect is most noticeable when the weight is towards the end of the rod: it tends to emphasise very strongly the swing of the rod. If you like the feel of a weight on the rod, you could also try some other materials such as lead fishing weights. Some dowsers, especially those doing outdoor work, greatly prefer these moveable weights; I don’t, as it happens, partly because with them the rods swing around more than I like and partly because they tend to pull my hands down and generally make a long outdoor session that much more tiring for me. But as usual, it’s your choice: see what works best for you.

So far we’ve made all our angle rods out of one kind of metal or another. But there’s nothing special about that: we need a material for the rod that’s long, thin and as close to circular in cross-section as will turn easily in our hands, and the most common sources of materials that fit that description are metal, such as the ubiquitous wire coat-hanger. We could just as easily make it of some other material, as long as it fulfils our mechanical requirements: in fact some dowsers have what you might call a magical objection to using metals at all, saying it frightens the energies away (whatever those might be). Try it out: see if you agree with them. In any case, it’s worthwhile getting into the habit of being inventive, of always being willing to try something new:

Don’t panic if you couldn’t think of anything else to use: it really doesn’t matter, this is a workbook, not a competition. The point of that exercise was to re-emphasise a theme we’ll be returning to throughout this book, namely inventiveness to find what works best for you.

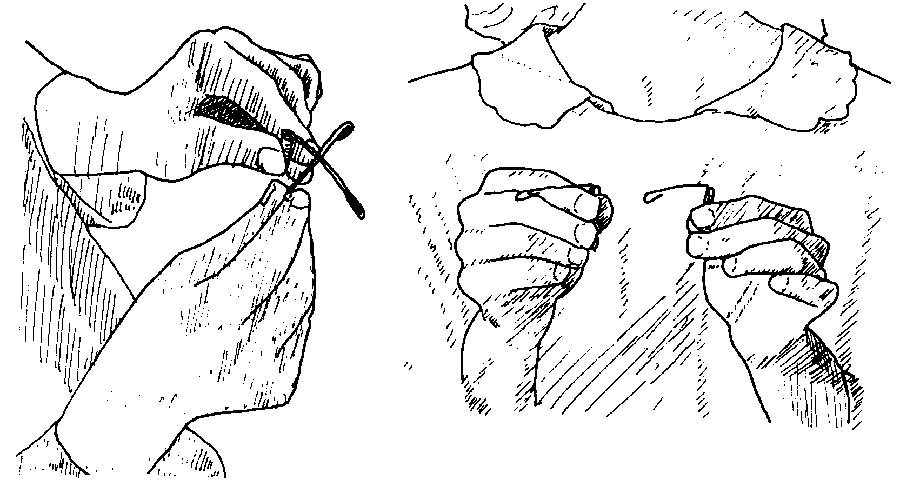

Inventiveness has to stop somewhere, and even I was surprised when someone turned up at one of my groups with a beautiful pair of miniature angle rods, to be held between finger and thumb: we’d played with changing the length of the rods, of course, but I hadn’t thought of changing the scale of the rods that drastically (see Fig. 3.2).

Figure 3.2: Miniature angle rods

He’d designed them for use in map-dowsing, which is something we’ll look at later, but they’re an interesting variant of angle rods to play with anyway:

Even with rods this small, you’ll soon get used to watching the rods out of the corner of your eye, so that you can concern yourself more with where you’re going, where you’re standing – much as with riding a bicycle. And as with the bicycle, it’s at that stage that everything suddenly becomes much easier: you don’t have to think about balancing, you just do it.

In no time at all you’ll find that you can just pick up almost anything that you could use as a pair of angle rods, adjust it to whatever balance feels comfortable for you, and get going. All it takes is practice!

3.2 Mind games

The other half of being comfortable in dowsing is being confident in yourself and in what you’re doing. So: what are we doing?

In some ways, to be honest, we don’t know. We do know that we’re aiming to use those reflex muscle responses to point out when we’ve found something: but we don’t really have a clue how we do it. We just, well, do it. Somehow.

This is where most people wander off into theory, and where I will simply sidestep the whole issue by saying that it’s entirely coincidence and mostly imaginary.

What? Entirely coincidence and mostly imaginary?

To make sense of that, we’d better take a brief diversion at this point into some mind games, and then forget the whole subject until Chapter 10.

What we’re doing is, literally, looking for a coincidence: a co-incidence – with the hyphen emphasised – of where we are and what we’re looking for. (You could also say event – it sounds more scientific than ‘co-incidence’, if not quite so precise). Just like all our other senses, we’re using this ‘dowsing sense’, this merging of other senses, to pick out a change in the surroundings that’s meaningful to us, using clues that we choose as being meaningful – such as the muscular twitch that we’ve trained ourselves to recognise as the dowsing response.

The way that we assign meaning and select ‘meaningfulness’ is through what we see as the context of the event, which we describe through ideas and images – in other words, in what is, literally, an image-inary way. We learn to recognise (or, more accurately, choose) that certain things are meaningful, while others aren’t: this movement of the rods was significant, while that movement was simply my being careless and tripping over the edge of the carpet. We interpret the coincidences according to what we see as the context of those coincidences.

This is true for all of our forms of perception: dowsing is no different. I hold in my mind an image of what I’m looking for - “I’m looking for a water-pipe” – and until I’ve found it, it is, of course, entirely imaginary. What we’re learning to do in dowsing is to find a way to bring an imaginary world – what we’ve decided we’re looking for – and the tangible object in the physical world – the water-pipe, in this case – together, through the overall awareness of our senses. Or, to put it in a simpler way, we’re trying to find a way to get us to know that we’ve coincided with the water-pipe when we didn’t know where it was in the first place.

So we need to know when that event, that coincidence has happened. And to do that we need to have a clear understanding of three simple questions with sometimes not-so-simple answers:

- Where am I looking?

- What am I looking for?

- How am I looking?

All dowsing techniques address these questions in various ways, but let’s look at them in more detail as they relate to the use of our angle rods.

3.2.1 Where am I looking?

In order to make sense of a co-incidence – the rods’ response – we have to know precisely where it’s occurred. At first sight the answer to “Where am I looking?” seems obvious: I’m looking here. But stop and think for a moment: just where is ‘here’?

We know that ‘here’ is somewhere down by your feet: but in practice we usually need to be more precise than that. We need to know exactly where that pipe is; we need to know the exact place on the ground meant by that co-incidence of the crossing of your angle rods. Since that point isn’t obvious, we choose one.

This perhaps sounds a little strange, but it really is no different from the way we choose to listen to one person rather than another at some noisy party. Our perceptual systems can – and do – select out the timing of information, giving us warnings about relevant co-incidences: here we’re just making use of that inherent ability of ours in a slightly different way. We choose where ‘here’ is.

The hard part, then, is making sure that the rods know, so to speak, of where your choice of ‘here’ happens to be. So just tell them: it’s as simple as that. As with riding a bicycle, your senses will do the rest, once they know what you want. But if you can’t make up your mind, there’s no way that your dowsing can be accurate. So choose.

With angle rods, the best choice is often ‘the leading edge of the leading foot’:

By choosing to mark ‘here’ in different ways, you can resolve some practical problems that might otherwise be awkward. For example, it’s difficult to track a pipe close to a wall, because the rods tend to get tangled up with the wall as you walk closer to it. So one solution is to change the way you mark ‘here’, simply by walking backwards:

You can mark ‘here’ in any way you like, as long as you can make clear to yourself where ‘here’ is. If you’re using a pendulum for dowsing (as in the next chapter) rather than angle rods, you can use a hand or a finger to point out ‘here’, or point in a particular direction, with the line of ‘here’ stretching outward from you to infinity. Or you can be more imaginative, and say that ‘here’ is the place represented by some point on a photograph or a map – hence map-dowsing, of which more later.

It’s up to you. It’s all up to you. That’s the great strength of dowsing; but it’s also the reason why it can sometimes take a great deal of practice and discipline to get it to work well.

3.2.2 What am I looking for?

The rods’ reaction at some place shows that we’ve found a co- incidence with something there: but it’s difficult to know what they mean unless we know that we’re looking for something. We have to tune the radio, so to speak; we have to be selective, we have to choose.

So almost before we do anything else, we have to decide what we’re looking for: otherwise (to use our anthropomorphic analogy) the rods won’t know what to respond to, to mark the co-incidence that we’d like. One the real disciplines in dowsing is in learning how to be clear, precise and specific about what it is that you’re looking for.

One way to do this is simply to hold it in your mind: in other words, say to yourself “I’m looking for…” (whatever it is – a water-pipe, in our previous examples). Frame it in your mind: imagine it, image it:

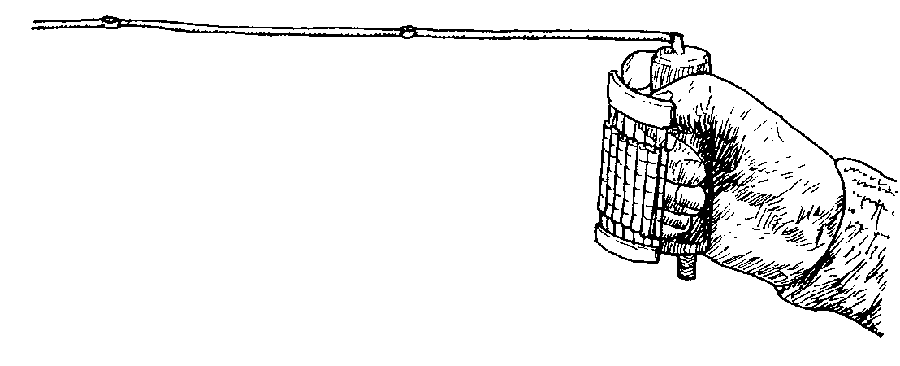

Another common method is to carry a sample of pipe-material with you, to use as a tangible reminder of what it is that you’re looking for. One commercially-made dowsing kit, designed for use by surveyors, actually came complete with a set of samples of piping materials wrapped around one of the rod-handles – see Fig. 3.3. (For historical reasons, American dowsers tend to refer to this kind of sample as a ‘witness’). Or you could write it down on a piece of paper as a kind of verbal sample – “I’m looking for a water-pipe that’s like this” – or perhaps draw it: anything, as long as it’s a useful prompt to make it clear to your rods (in other words you) what you want their response to coincide with.

Figure 3.3: ‘Revealer’ rods with set of samples

You can, of course, find things other than water-pipes with your angle rods. In principle, you could find anything, since all you’re doing is using the rods to indicate the co-incidence between where you are and what you’re looking for. In practice, of course, we tend to look for more tangible objects: cables, keys, cashew nuts or whatever. All we do is change the rules: tell the rods that we’re looking for this, rather than for the pipe as before. Try it:

Whenever you’re using the rods, there’s always a little ‘noise’ mixed up with the signal: the rods drifting this way and that at times, for no apparent reason. At this stage you’ll probably be just beginning to recognise when there’s a real ‘signal’ response from the rods: there’s a quite different feel to it, a sense of ‘this one’. But while most of the other twitches and wanderings may well be meaningless, don’t be too quick to dismiss them all as ‘noise’: sometimes they’re trying to tell you something.

The same is true at that noisy party, of course: sometimes you’ll hear interesting snatches of conversation that drift out of the background babble – or important messages such as “Food’s ready!”. The dowsing equivalent would be the rods giving you further information about what you’re looking at, such as a joint or branch in the pipe, or the direction the pipe’s going in; or else telling you that you’re walking over something that’s not specifically what you’re looking for, but may be relevant and that you ought to know about, such as an electrical cable that needs repair.

One of the important tricks in dowsing is to leave some kind of space in the rules that you’re using, so as to allow these ‘not- in-the-mainstream’ messages to come through – rather as you’d keep half an ear open, so to speak, for other information at the party. As at the party, the best indicator is always that clear ‘feel’ when something is meaningful – it ‘stands out from the crowd’, we would say; but one way to help it is to build other types of responses, in addition to ‘X marks the spot’, into the rules that you set up for your rods to follow.

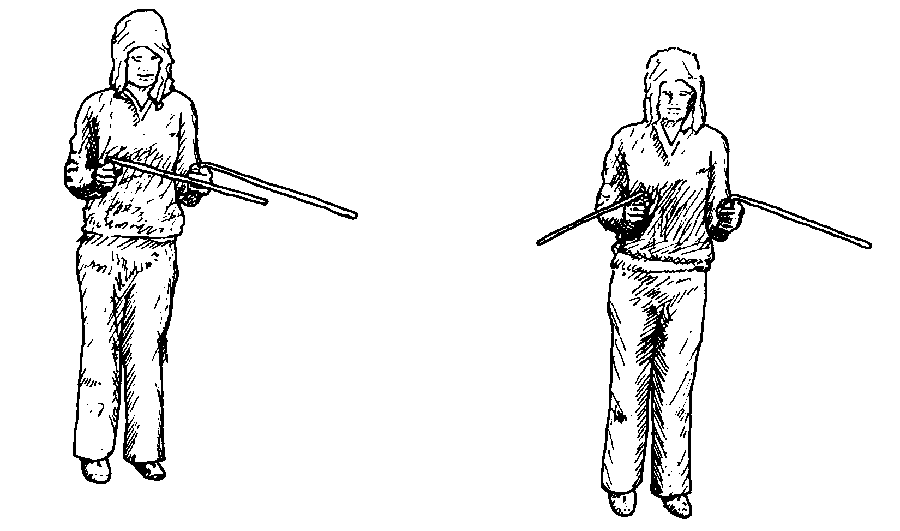

Figure 3.4: Some more responses: direction and ‘something else’

A good example of one of these extra rules, or extra response types, is what we might call ‘they went thataway’, for which the rods both move parallel to point out a different direction (see Fig. 3.4). You could also set up that the rods move in a similar way to point out a shape or an edge – particularly useful if you’re trying to find buried walls at an archaeological site, for example. And another move is what I call the ‘anti-cross’, in which both rods swing outward instead of inward – I set this up in my list of rules to tell me that there’s something else important here, even if I’ve not specifically been looking for it (somewhat the equivalent of hearing “Food’s ready!” during your conversation at the party).

Practice with this for a while, switching between the two sets of rules: ‘I’m looking for the pipe (or whatever)’ and ‘I’m looking for the direction of the pipe’.

Having found the direction, it would now be useful to track along the pipe instead of marking it with a series of passes of ‘X marks the spot’. We can do this by asking the rods to continue to point out the direction that we should move in so that we can walk directly along the course of the pipe:

Don’t be too concerned if what you’ve mapped out is best described as a drunkard’s walk, rather than what was supposed to be the straight line of the pipe. How well could you travel in a straight line when you first learnt to ride a bicycle? Not exactly a straight path then, was it? The same is true here: until you’ve had a lot more practice, you will often tend to ‘hunt’, or overshoot the line, over-correcting each time you cross the pipe – hence the wandering line that you’ve marked out. The overall course probably will be correct, even now, when you come to check it out. Once again, all you need is practice!

And along with that you’ll also need practice at that balance of looking for something specific, some specific co-incidence, whilst at the same time keeping yourself open and aware for other possibilities, other information:

What we’re doing in dowsing, in effect, is building layer upon layer of rules for the rods to follow, to tell it exactly what co-incidence to respond to. Layer upon layer of rules within rules, sub-clauses, ifs, buts and perhapses, all building up as precise a description as we can of what exactly it is that we’re looking for and in what context (or contexts) we’re looking for it. In a way, we’re programming the response of the rods, rather like programming a computer.

But the computer here is not some external machine, but our own overall awareness, sensing for some specific co-incidence. The computer program has its input and output; the input here is that merging of all our senses into what seems at times to be a separate sense, and the output is directed into one place, the reflex muscle responses that we see and feel in the movement of the angle rods. The catch, as in computing, is ‘garbage in, garbage out’: if you don’t take enough care over the instructions you set up for that ‘bio-computer’, the results will, all too often, turn out to be nonsense, rubbish, garbage. So it’s important to consider not just what you’re doing, but also how you’re doing it, what your mental ‘set’ or state of mind is while you’re working.

Which brings us back to the third of those three questions that we need to ask, namely:

3.2.3 How am I looking?

The way in which you approach any skill is important; but in dowsing it’s absolutely critical. Approach your work with the wrong kind of mind-set, and you’ll usually find yourself getting nowhere slowly. Your mind-set matters. A lot.

As with riding a bicycle, there’s a delicate balance to be learnt: a balance of mind rather than body. Assume you can’t do it and, yes, you’re right, you can’t do it. Alternatively, assume that you know exactly how to do it, you know everything there is to know about it, and, strangely enough, you’ll probably find that you can’t do it. What actually does work is even stranger: try extremely hard for a while, and then quite deliberately give up. Just let it happen, without trying, and it works, as if by itself, with you doing ‘no-thing’ to make it do so.

Do nothing, and nothing happens; do something, trying to make it happen, and and once again nothing happens; instead, you have to reach that delicate balance of ‘doing no-thing’.

It’s perhaps easiest to understand that balance by exaggerating what not to do:

Here we’ve been exaggerating, of course, but those nibbling little doubts and under-confidence with which most people start are likely to have much the same effect. The trouble is that those inner doubts are subtle, so their effects are subtle too. Learn to watch your own responses closely, and you’ll see how your dowsing can become a useful mirror of your current state of mind.

The same is true of over-confidence, in that it can wreck your results just as effectively as doubt:

Well, it may have given your confidence – and your results – a boost for a while, but the most common ending of that is the phrase ‘Pride comes before a fall’. A big one. A long, long drop. If you ever reach a point where you’re certain you know it all, that’s when you’re likely to be just that little bit over- confident – with disastrous results. Every skill is a learning experience, for a lifetime: you never do get it perfect. And if you spend much energy on protecting your ego from the inevitable bruises, you’ll never get much done. So again, your dowsing can become a useful mirror of that aspect of your current state of mind: by watching your results, you can watch you at the same time.

Over-confidence and under-confidence are variations on a much more wide-ranging theme of assumptions. We assume things to be such-and-such a way; since these then form part of our mind-set while we’re working, they’re included in that list of rules that we set up for the rods to respond to in marking the coincidence we’ve said is going to be meaningful. So the rods, obliging as ever, will respond exactly according to that list of instructions – leaving you to disentangle the confusion of whether they responded to a real object like a pipe, or an imaginary ‘object’ like “I can’t do this”. If your instructions to the rods – your instructions to you, that combining of your senses – are riddled with assumptions, it’s not going to be too likely that your results will be of much use.

This applies not only to attitudes like over-confidence, but also to assumptions about repeatability and the like. Let’s take a typical example:

It’s up to you. Your choice. You can spend all of your time looking for imaginary objects – which your rods will quite happily find for you in some imaginary world, but not, unfortunately, in this so-called ‘objective’ world that we happen to share with everyone else. Or you can pay attention to what assumptions you’re placing on the way that you work: in which case you might well get some useful results. (With practice, of course!)

There are occasions, though, where you can put the blocking effect of assumptions to practical use, by deliberately ignoring some information that would otherwise get in the way – rather like shutting out the gabbling of some load-mouthed oaf at the party so that you can listen to the quiet-voiced woman next to you. In other words, we declare that something is ‘noise’, even if it was useful information a few moments ago. Just ignore it, tell yourself that it isn’t there any more – rather as you would wish was the case with the loud-mouthed oaf!

One example would be when trying to find something with water in it, other than the water-pipe:

Properly used, this kind of ‘selective ignore-ance’ can be an immensely powerful tool. We have in fact used it already, back in Exercise 25, to get the rods to show us direction rather than position; and again in Exercise 26, where we followed the course of that one pipe and ignored any others that we might have crossed.

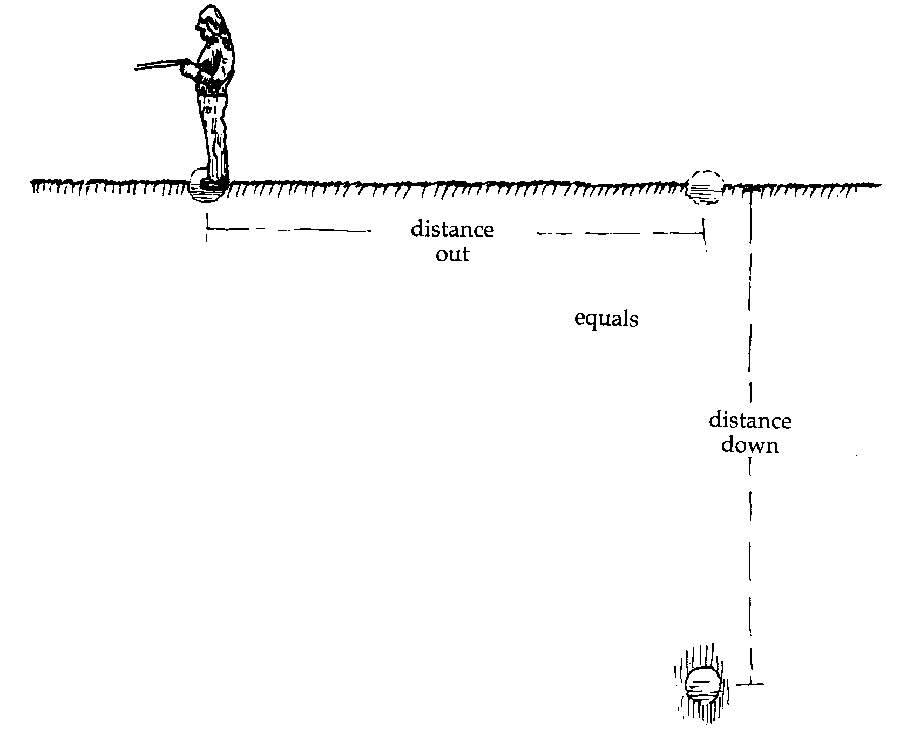

Figure 3.5: Finding depth with the ‘Bishop’s Rule’

We can use a similar process to find the depth of the pipe, with a technique known as the ‘Bishop’s Rule’ in dowsing circles for at least a couple of centuries (see Fig. 3.5). We mark a point directly above the pipe; then when we get another response from the rod, the distance back to where we started will be the same as the depth of the pipe at our starting point – in other words, ‘distance out equals distance down’.

In all of this, do be inventive, and do remember to check things out for yourself. For example, some dowsers find that the Bishop’s Rule works in a rather different way: ‘distance out’ may be half or twice distance down, or some other factor. And that won’t be very helpful if you’ve presumed that someone else’s assumptions about experience (which is all a ‘rule’ is in reality) must apply to you: you may find yourself digging a great deal further than you thought to find that pipe!

And remember to maintain that delicate mental balancing act of ‘doing no-thing’: asking politely for things to happen, and letting things happen the way they want to in return. It is a subtle balance, and it does take practice: but if you’ve been doing the exercises rather than just reading them, you’ll be well on the way to reaching that balance by now.