2: A practical introduction

Dowsing is a practical skill, and as such only makes real sense in practice. So if you’ve never done any dowsing before, perhaps the first thing we need to do is get you started with some practical dowsing.

All dowsing work consists of identifying when the context of some small muscular twitch can be recognised as meaning something useful – such as the location of an underground pipe or a cable. As with riding a bicycle, we train ourselves to respond in a particular way to various bits of information that we select out from those that happen to be passing by.

On a bicycle, we pay particular attention to data received by our eyes and, especially, from the balance-detectors in the middle- ear, and we compare and merge those together to give instructions to muscles all over the body, to both balance and guide the bicycle. In dowsing we do something similar: but we seem to collect information from all of our senses, and direct it to just one set of muscles – usually the wrist muscles – to give the movement that indicates a response.

Because this movement is small and subtle, most dowsers use some kind of instrument, a mechanical amplifier such as a simple lever, to make the movement more obvious. Like the small side-wheels on your first bicycle, they make the learning stage easier; and, as with those side-wheels, they are something that we probably should, in the end, learn to outgrow.

But it’s true that it is much easier to use an instrument than to do without: something’s happening, you can see it and feel it much more easily. So much so that you’ll often feel that the dowsing rod is moving of its own accord, as if it has a life of its own. In fact, it hasn’t: it will always be your hand moving it. But that sense of it ‘being alive’ is usually a good indicator of when you’re allowing things to work, when you’re allowing all those internal senses to merge together within you to produce the end-results you need.

The other point that we need to recognise even at this stage is that there’s no one ‘right’ way to go about dowsing: there are no fixed rules, only the ways that work for you. But if anything goes, and anything can work, it’s difficult to know where to start. It’s much easier, at the beginning, to pretend that there is just one right way of doing it. Since we do need to start somewhere, we will begin with a set of perhaps rigid-sounding instructions: just note – as in fact you’ll find later in the book – that there are many variations, and if you feel uncomfortable with what I suggest here, do try something else until you find an approach that does feel right.

With that said, let’s get started.

2.1 Making a basic dowsing tool

The traditional dowsing tool is a V-shaped twig but, as you’ll discover later, it’s not exactly easy to use. So instead we’ll start with a pair of ‘angle rods’, sometimes known as ‘L-rods’ from their shape.

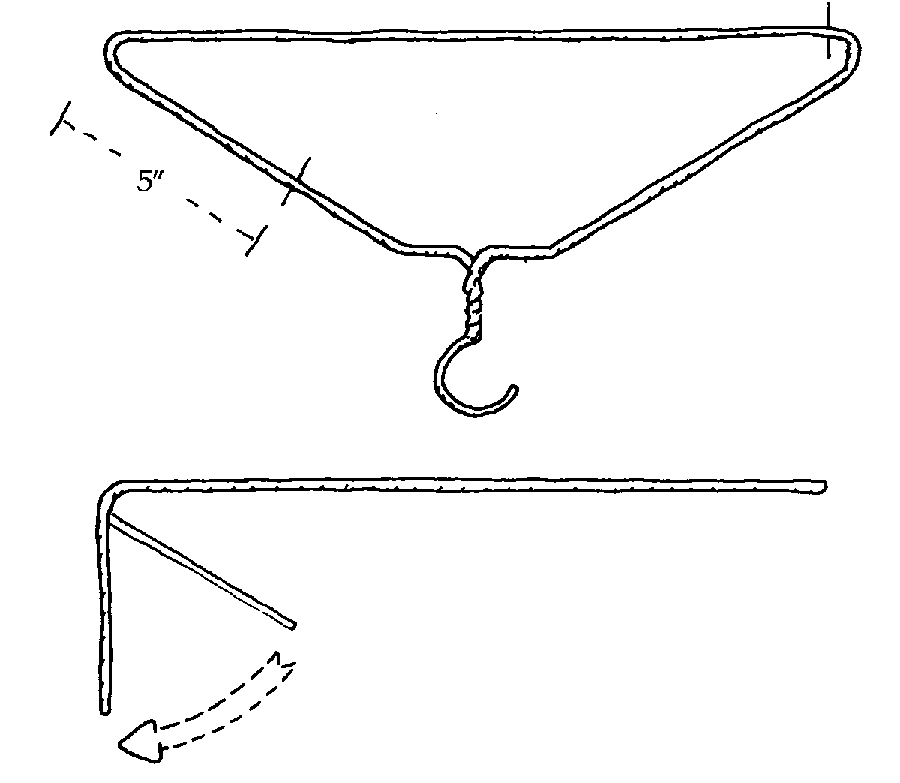

Figure 2.1: Making an L-rod from a coat-hanger

These can be made from anything that will bend into an ‘L’ and has a round enough cross-section to turn smoothly in your hand. Fencing wire, welding rod, electrical cable, plastic rod or even a pair of old knitting needles will do the job, but perhaps the easiest source-material to find is a wire coat-hanger.

Having made them, you now need to know how to hold them:

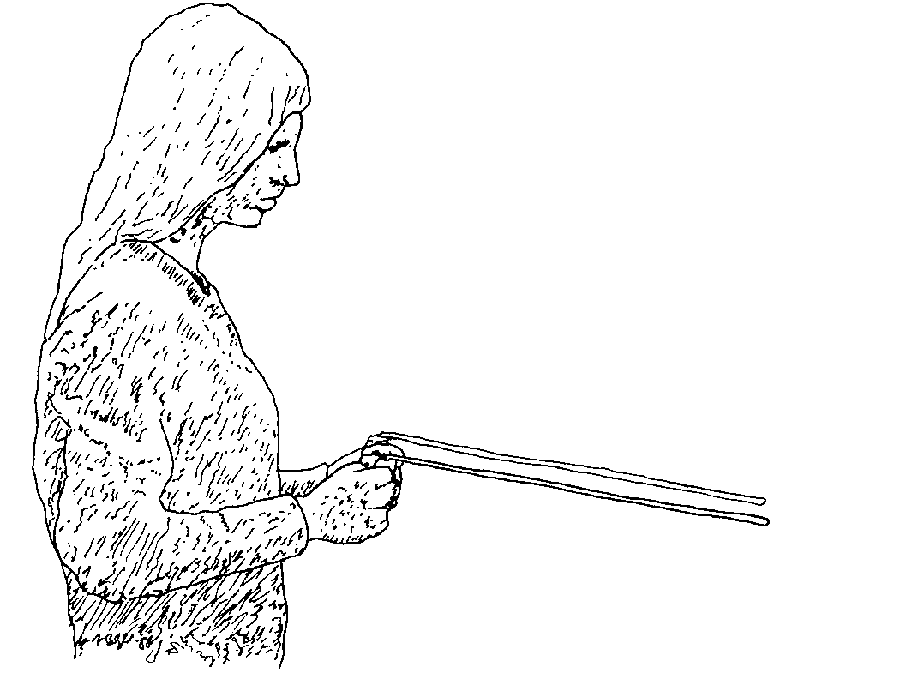

Figure 2.2: Holding L-rods

Held in this position, the rods are in a state of neutral balance, and will thus amplify and make obvious any small movement of your wrists, as the next exercise should show:

What we’re doing here is training the reflex response to come out in these wrist movements: a slight twisting of the wrist from side to side, which we can then see as a movement of the rods. The rods don’t move of their own accord: they’re actually amplifying the movement of your wrists. But in the next exercise, you should slowly find that it will seem that the rods are moving by themselves at your command:

Although this may sound a little strange, it’s actually no different from what we do when riding a bicycle. If you think too much about what your feet are doing or whether you’re balancing, you’re likely to fall off: instead, you concentrate on where you’re going, in other words treat the bicycle as an extension of you rather than as a separate ‘thing’ which you’re trying to control. That does take practice; that does take a certain amount of experience to change the all-too-conscious balancing efforts of your first few bicycle rides, to something where it’s so much a part of you that you don’t even notice the mechanics of what’s involved.

The same is true with these dowsing responses: it does take a little practice before it becomes automatic, before you completely stop thinking about what you’re doing, and instead concentrate on where you’re going, on what you want to do with the rods. So, before we move on:

One point you’ll notice is that when you let the rods ‘move by themselves’, they’ll move much more smoothly than if you move your hands deliberately. A technique that many dowsers use is to imagine that their rods are some kind of household pet that they’re watching and giving instructions and encouragement to, rather than something that they’re controlling; and you’ll probably find it easier to use a similar idea.

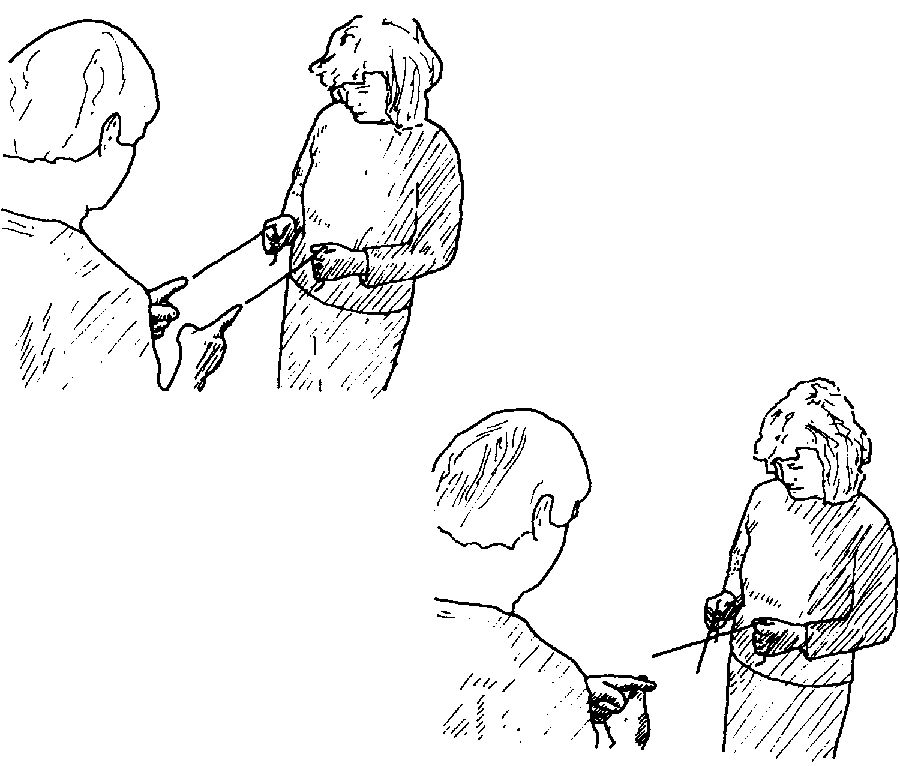

Figure 2.3: The ‘following fingers’ exercise

One way to illustrate this is to try the next exercise, for which you’ll need a partner:

This is, of course, a simple trick to redirect attention and stop the mind getting in the way. But it does work: it does make it easier to use the rods.

2.2 Extending your senses

In a way, though, we haven’t used the rods at all yet: all we’ve done is wrist-exercises, getting your reflexes used to the idea of what’s expected of them. In each of these exercises you’ve known exactly what’s going on, exactly where the requests for those movements were coming from – namely your own conscious awareness. What we now have to do is to find some responses to things that you don’t know. And that’s where the real magic starts:

What you’re likely to have had as results to that exercise is a mixture: a few movements you could attribute to plain physical causes such as tripping over the edge of the carpet; a few others where the rods seemed to move of their own accord, perhaps both to one side or the other, perhaps even crossing over; and, of course, a large amount of nothing much at all happening. That’s usual at this stage. But now remind yourself of that mental state you reached back in Exercise 5, where you could move the rods around simply by asking them politely to do so. If you didn’t ask them to move, they didn’t move; if you pushed them to move, it was obvious that you were faking it; but if you asked nicely and just let it happen by itself – ‘doing no-thing’, so to speak – things happened smoothly, cleanly, clearly. Now it’s not the action that happened there that we’re interested in, but the state of mind, of just letting things happen while at the same time setting up some limits or framework for things to happen in. With that in mind, let’s go back and do it again:

When you learn to ride a bicycle, there’s a knack to the balance which doesn’t come together and doesn’t come and doesn’t come until at some point – usually when you’ve just stopped trying – it all comes together and you have no real trouble from then on. The same is true of dowsing: there’s a real knack to the mental balance, the mental juggling-act we’ve called ‘doing no-thing’. Don’t worry if it’s all a little blurred at the moment: the knack, as with riding a bicycle, will come with time and practice.

2.3 Go find a pipe

At the beginning of this chapter I said that what we’re doing in dowsing is training ourselves to respond in a particular way to various bits of information that we select out from those that happen to be passing by. The key point there is that we select out from the mass of information those fragments that are relevant to what we’re looking for. If we didn’t do this, of course, the dowser’s rod would be about as useful as an open-band radio receiver: every channel being played simultaneously in a confusing cacophony of sensory images. It’s only when we select out, decide what we’re looking for, that we can merge those senses in a useful way into those reflex responses that we use in dowsing.

All our perceptual processes do this kind of separation for us, discriminating between what we choose as ‘signal’ and the rest of the background ‘noise’: it’s sometimes called the ‘cocktail-party effect’, from the way we can pick out a single conversation in the midst of the babble of a noisy party. To make sense of that kind of noise, we could use a variety of techniques: we might listen to the loudest talker, or point a directional microphone at someone. Or, more often, we can somehow just choose to listen, focus our attention on just one person, almost regardless of how loudly or quietly they’re talking, and let our senses merge together to do the rest. And it works.

One of the simplest ways of selecting something to look for in dowsing is exactly the same: just choose what you’re going to look for, and let your senses merge to do the rest. So, to complete this instant introduction to practical dowsing, let’s choose a simple example, namely looking for a water pipe in or around your house:

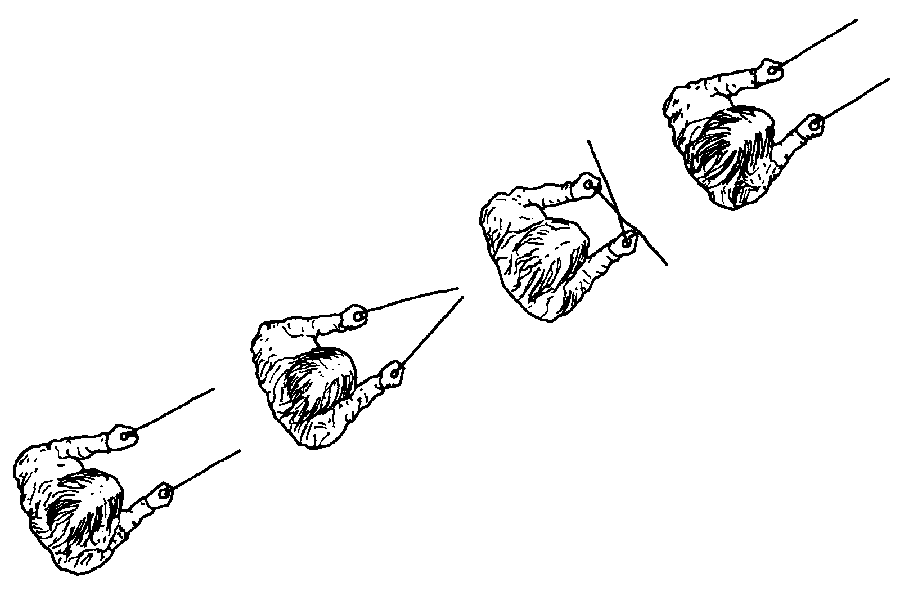

Figure 2.4: “X marks the spot” – a typical response

With the practice you’ve had by now, your response as you crossed the pipe should have been something like that shown in Figure 2.4: the rods cross as you walk over the pipe, and then open out parallel again. Don’t be surprised, though, if you overshoot the pipe a little, so that you get a slightly different location according to which direction you cross the pipe. (This is because your reflex responses aren’t fast enough yet: your body’s still a little uncertain of what to do when, rather like that wobbling stage of learning to ride a bicycle.) And don’t be too concerned if it didn’t work out that way: it doesn’t mean that you can’t dowse, it just means that you need more practice, of which you’ll find plenty as we go through the rest of this Workbook.

So let’s move on to look at that practice in rather more detail.