8. Integrating with authentication providers

Authorization is all well and good, but some constraints are pointless if the user is not known to the application. You could write a Dynamic constraint that only allows access on Thursdays - this doesn’t need to know anything about even the concept of a user; a Restrict constraint, on the other hand, uses Roles obtained from a Subject. The question is, what is a subject and how do we know who it is?

Imagine an application where you can post short messages and read the messages of others, something along the lines of Twitter. By default, you can read any message on the system unless the user has marked that message as restricted to only users who are logged into the application.. In order to write a message, you have to have an account and be logged in. We can sketch out a controller for this very simple application thus:

1 package be.objectify.messages;

2

3 import javax.inject.Inject;

4 import play.libs.F;

5 import play.libs.Json;

6 import play.mvc.Controller;

7 import play.mvc.Result;

8 import be.objectify.deadbolt.java.actions.SubjectPresent;

9

10 public class Messages extends Controller {

11

12 private final MessageDao messageDao;

13

14 @Inject

15 public MessagesController(final MessageDao messageDao) {

16 this.messageDao = messageDao;

17 }

18

19 public F.Promise<Result> getPublicMessages() {

20 return F.Promise.promise(messageDao::getAllPublic)

21 .map(Json::toJson)

22 .map(Results::ok);

23 }

24

25 @SubjectPresent

26 public F.Promise<Result> getAllMessages() {

27 return F.Promise.promise(messageDao::getAll)

28 .map(Json::toJson)

29 .map(Results::ok);

30 }

31

32 @SubjectPresent

33 public F.Promise<Result> createMessage() {

34 return F.Promise.promise(() -> body.asJson())

35 .map(json -> Json.fromJson(json, Message.class))

36 .map(messageDao::save)

37 .map(Results::ok);

38 }

39 }

This very simple app has a very simple routes file to go with it:

1 GET /messages/public be.objectify.messages.Messages.getPublicMessages()

2 GET /messages be.objectify.messages.Messages.getAllMessages()

3 POST /create be.objectify.messages.Messages.createMessage()

An authenticated user can access all three of these routes and obtain a successful result. An unauthenticated user would hit a brick wall when accessing /messages or /create - specifically, they would run into whatever behaviour was specified in the onAuthFailure method of the current DeadboltHandler.

This is a good time to review the difference between the HTTP status codes 401 Unauthorized and 403 Forbidden. A 401 means you don’t have access at the moment, but you should try again after authenticating. A 403 means the subject cannot access the resource with their current authorization rights, and re-authenticating will not solve the problem - in fact, the specification explicitly states that you shouldn’t even attempt to re-authenticate. A well-behaved application should respect the difference between the two.

We can consider the onAuthFailure method to be the Deadbolt equivalent of a brick wall. For a DeadboltHandler used by a RESTful controller, the status code should be enough to indicate the problem. If you have an application that uses server-side rendering, you may well want to return content in the body of the response. The end result is the same though - You Can’t Do That. Note the return type, a Promise containing a Result and not an Optional<Result> - access has very definitely failed at this point, and it needs to be dealt with.

1 public F.Promise<Result> onAuthFailure(final Http.Context context,

2 final String content) {

3 return F.Promise.promise(Results::forbidden);

4 }

Unlike onAuthFailure, the beforeAuthCheck method allows for the possibility that everything is fine. It’s perfectly reasonable to return an empty option from this method, indicating that no action should be taken and the request should continue unimpeded.

1 public F.Promise<Optional<Result>> beforeAuthCheck(final Http.Context context) {

2 return F.Promise.promise(Optional::empty);

3 }

This has the net effect of not getting in the way of the constraint; with this implementation, a user accessing /messages in our little application would receive a 403. But, our application aims to be well behaved and return a 401 when it’s needed, so a little more work is required. Because beforeAuthCheck is only called when a constraint has been applied, we can use this to trigger an authentication request if needed. In this application, we’re going to say that every constraint requires an authenticated subject to be present - do not confuse this with @SubjectPresent constraints in the example controller, the same would equally be true if we were using @Restrict or @Pattern. For the more advanced app that uses the subject-less dynamic rule of Thursdays-only, either more logic is required or (preferably) a different DeadboltHandler implementation is used.

The logic here is simple - if a user is present, no action is required otherwise short-cut the request with a 401 response.

1 public F.Promise<Optional<Result>> beforeAuthCheck(final Http.Context context) {

2 return getSubject(context).map(maybeSubject ->

3 maybeSubject.map(subject -> Optional.<Result>empty())

4 .orElseGet(() -> Optional.of(Results.unauthorized())));

5 }

On the other hand, you may choose to never implement any logic in beforeAuthCheck and instead have the behaviour driven by authorization failure. The choice is entirely in the hands of the implementor; personally, I tend to use onAuthFailure to handle the 401/403 behaviour, because it removes the assumptions required by implementing checks in beforeAuthCheck.

It will become very clear, very quickly, the same approach is used for all authentication systems; this means that swapping out authentication without affecting authorization is both possible and trivial. We’ll start with the built-in authentication mechanism of Play and adapt from there; with surprisingly few changes, you’ll see how we can move from basic authentication through to using anything from Play-specific OAuth libraries such as Play Authenticate and even HTTP calls to dedicated identity platforms such as Auth0.

8.1 Play’s built-in authentication support

Play ships with a very simple interceptor that requires an authenticated user to be present; there’s no concept of authorization. It uses an annotation-driven approach similar to that of Deadbolt, allowing you to annotate either entire controllers at the class level, or individual methods within a controller.

1 @Security.Authenticated

2 public F.Promise<Result> getAllMessages() {

3 return F.Promise.promise(messageDao::getAll)

4 .map(Json::toJson)

5 .map(Results::ok);

6 }

By default, the Security.Authenticated annotation will trigger an interceptor that uses Security.Authenticator to look in the session for a value mapped to "username" - if the value is non-null, the user is considered to be authenticated. If you want to customize how the user identification string is obtained, you can extend Security.Authenticator implement your own solution.

1 package be.objectify.messages.security;

2

3 import java.util.Optional;

4 import javax.inject.Inject;

5 import be.objectify.messages.dao.UserDao;

6 import be.objectify.messages.models.User;

7 import play.mvc.Http;

8 import play.mvc.Security;

9

10 public class AuthenticationSupport extends Security.Authenticator {

11

12 private final UserDao userDao;

13

14 @Inject

15 public AuthenticationSupport(final UserDao userDao) {

16 this.userDao = userDao;

17 }

18

19 @Override

20 public String getUsername(final Http.Context context) {

21 return getTokenFromHeader(context).flatMap(userDao::findByToken)

22 .map(User::getIdentifier)

23 .orElse(null);

24 }

25

26 private Optional<String> getTokenFromHeader(final Http.Context context) {

27 return Optional.ofNullable(context.request().headers().get("X-AUTH-TOKEN"))

28 .filter(arr -> arr.length == 1)

29 .filter(arr -> arr[0] != null)

30 .map(arr -> arr[0]);

31 }

32 }

The class of this customized implementation can then be passed to the annotation with @Security.Authenticated(AuthenticationSupport.class). However, all mention of Deadbolt’s constraints have vanished and so we’ve replaced a fine-grained authorization system with a coarse-grained authentication-only system. To fix this, we need to revert back to using Deadbolt in the controller and move AuthenticationSupport (or even the basic Security.Authenticator) integration into the DeadboltHandler.

1 package be.objectify.messages.security;

2

3 import java.util.Optional;

4 import javax.inject.Inject;

5 import be.objectify.deadbolt.core.models.Subject;

6 import be.objectify.deadbolt.java.AbstractDeadboltHandler;

7 import be.objectify.messages.dao.UserDao;

8 import play.libs.F;

9 import play.mvc.Http;

10 import play.mvc.Result;

11 import play.mvc.Results;

12

13 public class MyDeadboltHandler extends AbstractDeadboltHandler {

14

15 private final AuthenticationSupport authenticator;

16 private final UserDao userDao;

17

18 @Inject

19 public MyDeadboltHandler(final AuthenticationSupport authenticator,

20 final UserDao userDao) {

21 this.authenticator = authenticator;

22 this.userDao = userDao;

23 }

24

25 @Override

26 public F.Promise<Optional<Result>> beforeAuthCheck(final Http.Context context) {

27 return getSubject(context).map(maybeSubject ->

28 maybeSubject.map(subject -> Optional.<Result>empty())

29 .orElseGet(() -> Optional.of(Results.unauthorized())));

30 }

31

32 @Override

33 public F.Promise<Optional<Subject>> getSubject(final Http.Context context) {

34 return F.Promise.promise(() ->

35 Optional.ofNullable(authenticator.getUsername(context))

36 .flatMap(userDao::findByUserName)

37 .map(user -> user));

38 }

39

40 @Override

41 public F.Promise<Result> onAuthFailure(final Http.Context context,

42 final String content) {

43 // you could also use the behaviour of the authenticator, e.g.

44 // return F.Promise.promise(() -> authenticator.onUnauthorized(context));

45 return F.Promise.promise(() -> forbidden("You can't do that"));

46 }

47 }

There are three things going on here, only one of which is explicitly tied into the authentication system, and that is getSubject. Of the other two methods, onAuthFailure gives an arbitrary (but hopefully meaningful) response and beforeAuthCheck is essentially generic code. There is scope here for performance improvements and will depend on your specific implementations; for example, the user retrieved from the database by the authenticator can be stored in context.args for re-use by the Deadbolt handler.

1 public class AuthenticationSupport extends Security.Authenticator {

2

3 // other methods

4

5 @Override

6 public String getUsername(final Http.Context context) {

7 final Optional<User> maybeUser = getTokenFromHeader(context).flatMap(userDao::find\

8 ByToken);

9 return maybeUser.map(user -> {

10 context.args.put("user", maybeUser);

11 return user.getIdentifier();

12 }).orElse(null);

13 }

14 }

15

16 public class MyDeadboltHandler extends AbstractDeadboltHandler {

17

18 // other methods

19

20 @Override

21 public F.Promise<Optional<Subject>> getSubject(final Http.Context context) {

22 return F.Promise.promise(() -> (Optional<Subject>)context.args.computeIfAbsent(

23 "user",

24 key -> {

25 final String userName = authenticator.getUsername(context);

26 return userDao.findByUserName(userName);

27 }));

28 }

29 }

8.2 Third-party user management

I like the concept of third-party user (or identity) management. It minimizes sensitive data held locally, provides features like multifactor authentication and provides a unified API for multiple authentication sources. This last feature makes it very easy to create a simple integration point with Deadbolt, driving interaction with the user management on a per-event basis (with a little caching thrown in). The sequence for this looks a little complicated, but it can be broken down into 4 distinct steps:

- the initial authentication

- subsequent use of cached user details

- re-retrieving user details when the cache doesn’t contain them

- re-authenticating when the user’s authentication has expired on the user management platform

If you’re using Deadbolt, it’s reasonable to assume you have one of two security models - either all actions require authorization or some actions require authorization, and that authorization may simply be “a user must be present”. As a result, the point the initial authentication occurs depends on your application. The good news, as far as this requirement goes, is the implementation is both quite simple and common to all cases. It comes down to the implementation of the onAuthFailure method of your DeadboltHandler, and might look something like this:

1 public F.Promise<Result> onAuthFailure(final Http.Context context,

2 final String contentType) {

3 return F.Promise.promise(login::render)

4 .map(Results::unauthorized);

5 }

But wait, this is wrong! As discussed above, this assumes that all authorization failure occurs because there is no user present, and this ignores the difference between 401 Unauthorized and 403 Forbidden. A better implementation will take this into account, by checking if there is a subject present. If there is a subject present, it’s a 403; if there isn’t, it’s a 401 and we can redirect to somewhere the user can log in.

1 public F.Promise<Result> onAuthFailure(final Http.Context context,

2 final String contentType) {

3 return getSubject(context).map(maybeSubject ->

4 maybeSubject.map(subject ->

5 Optional.of((User)subject))

6 .map(denied::render)

7 .orElseGet(() -> login.render()))

8 .map(Results::unauthorized);

9 }

There’s still a problem here - while the rendered output observes the difference between unauthorized and forbidden, but the HTTP status code is hard-wired to a 401. One more tweak should fix this.

1 @Override

2 public F.Promise<Result> onAuthFailure(final Http.Context context,

3 final String s) {

4 return getSubject(context)

5 .map(maybeSubject ->

6 maybeSubject.map(subject ->

7 Optional.of((User)subject))

8 .map(user ->

9 new F.Tuple<>(true,

10 denied.render(user)))

11 .orElseGet(() ->

12 new F.Tuple<>(false,

13 login.render(clientId,

14 domain,

15 redirectUri))))

16 .map(subjectPresentAndContent ->

17 subjectPresentAndContent._1

18 ? Results.forbidden(subjectPresentAndContent._2)

19 : Results.unauthorized(subjectPresentAndContent._2));

20 }

Integrating with Auth0

Auth0 is a great identity management platform, and I’m not writing that just because they gave me a t-shirt. One of the nice features they offer is a whole bunch of code you can pretty much drop into your application, including code for a Play 2 Scala controller. Since we’re in the Java portion of the book, and the Java example provided by Auth0 uses the JEE Servlet API, I’ve rewritten the Scala version for Java. This was the only customization required, which I have to say was pretty impressive - the total time to integrate and have a working solution was less than 15 minutes.

There are three core elements to the solution. These are, in no particular order,

- a log-in page

- a controller to receive callbacks from Auth0

- a DeadboltHandler implementation

I’ve also added a small utility class called AuthSupport to help with the cache usage, which also makes testing easier, but this contains code that could happily live in the controller.

A working example for this section can be found at auth0-integration. To run it, you will need to create an application on Auth0 and fill in the client ID, client secret, etc, into conf/application.conf. For the redirect URI, you can use http://localhost:9000/callback - don’t forget to adjust the port if necessary.

AuthSupport

This class has two simple function - it standardises the key used for caching the subject, and it wraps the cache result in an Optional.

1 package be.objectify.examples.auth0.security;

2

3 import java.util.Optional;

4 import javax.inject.Inject;

5 import javax.inject.Singleton;

6 import be.objectify.deadbolt.core.models.Subject;

7 import be.objectify.examples.auth0.models.User;

8 import play.cache.CacheApi;

9 import play.mvc.Http;

10

11 /**

12 * Utility methods for user caching.

13 *

14 * @author Steve Chaloner (steve@objectify.be)

15 */

16 @Singleton

17 public class AuthSupport {

18

19 private final CacheApi cache;

20

21 @Inject

22 public AuthSupport(final CacheApi cache) {

23 this.cache = cache;

24 }

25

26 public Optional<User> currentUser(final Http.Context context)

27 {

28 return Optional.ofNullable(cache.get(cacheKey(context.session().get("idToken"))));

29 }

30

31 public String cacheKey(final String key)

32 {

33 return "user.cache." + key;

34 }

35 }

The log-in page

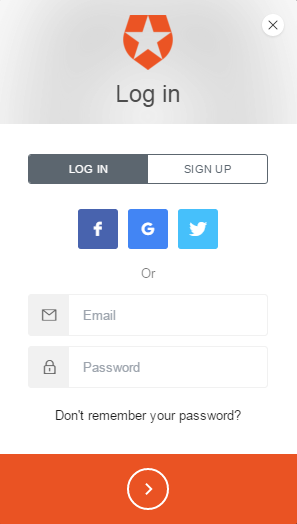

In order to log in, Auth0 provide a JavaScript solution that customises the form based on your configuration options; for example, an app registered in Auth0 for username/password support plus a couple of OAuth providers will receive a form that reflects those choices. The simplest possible implementation of a log-in page, without concern for appearance, is as follows.

1 @(clientId: String, domain: String, redirectUri: String)

2

3 <!DOCTYPE html>

4 <html lang="en">

5 <body>

6 <div id="root">

7 Log-in area

8 </div>

9 <script src="https://cdn.auth0.com/js/lock-7.12.min.js"></script>

10 <script>

11 var lock = new Auth0Lock('@clientId', '@domain');

12 lock.show({

13 container: 'root',

14 callbackURL: '@redirectUri',

15 responseType: 'code',

16 authParams: { scope: 'openid profile' }

17 });

18 </script>

19 </body>

20 </html>

In the browser, you now have a completely functional log-in form that will trigger the authentication flow. Once the form is submitted, Auth0 takes over until the authentication requirements are satisfied and then we receive a callback.

The controller

The bulk of the logic is contained here, and this code is reasonably generic - barring the User and UserDao classes, this code can be used in any Play 2 application. In broad terms, three things happen during a successful authentication flow - all of these are rooted in the callback method of the controller.

- The controller receives a callback, in the form of a HTTP request from Auth0 containing an authorization code.

- The controller makes a HTTP request to Auth0 to get the token.

- The controller makes a HTTP request to Auth0 to get the user details.

1 public F.Promise<Result> callback(final F.Option<String> maybeCode,

2 final F.Option<String> maybeState) {

3 return maybeCode.map(code -> getToken(code) // get the authentication token

4 .flatMap(token -> getUser(token)) // get the user details

5 .map(userAndToken -> {

6 // userAndToken._1 is the user

7 // userAndToken._2 is the token

8 cache.set(authSupport.cacheKey(userAndToken._2._1),

9 userAndToken._1,

10 60 * 15); // cache the subject for 15 minutes

11 session("idToken",

12 userAndToken._2._1);

13 session("accessToken",

14 userAndToken._2._2);

15 return redirect(routes.Application.index());

16 }))

17 .getOrElse(F.Promise.pure(badRequest("No parameters supplied")));

18 }

This callback provides the starting point for further interaction with Auth0 by giving us an authorization code. With this code, we can request token information; access_token allows us to work with the subject’s attributes, and ´id_token´ is a signed Json Web Token used to authenticate API calls.

1 private F.Promise<F.Tuple<String, String>> getToken(final String code) {

2 final ObjectNode root = Json.newObject();

3 root.put("client_id",

4 this.clientId);

5 root.put("client_secret",

6 this.clientSecret);

7 root.put("redirect_uri",

8 this.redirectUri);

9 root.put("code",

10 code);

11 root.put("grant_type",

12 "authorization_code");

13 return WS.url(String.format("https://%s/oauth/token",

14 this.domain))

15 .setHeader(Http.HeaderNames.ACCEPT,

16 Http.MimeTypes.JSON)

17 .post(root)

18 .map(WSResponse::asJson)

19 .map(json -> new F.Tuple<>(json.get("id_token").asText(),

20 json.get("access_token").asText()));

21 }

With these token data, we can retrieve the subject attributes. At this point, it’s possible to cache the subject to reduce network calls. In this example, we have no concept of a database and so we rely entirely on Auth0 to provide subject information. If you keep some user information local, this might be a good place to either create or retrieve that information.

1 private F.Promise<F.Tuple<User, F.Tuple<String, String>>>

2 getUser(final F.Tuple<String, String> token) {

3 return WS.url(String.format("https://%s/userinfo",

4 this.domain))

5 .setQueryParameter("access_token",

6 token._2)

7 .get()

8 .map(WSResponse::asJson)

9 .map(json -> new User(json.get("user_id").asText(),

10 json.get("name").asText(),

11 json.get("picture").asText()))

12 .map(localUser -> new F.Tuple<>(localUser,

13 token));

14 }

Logging out simply requires the token information to be removed from the session, and the removal of the subject from the cache.

1 public F.Promise<Result> logOut() {

2 return F.Promise.promise(() -> {

3 final Http.Session session = session();

4 final String idToken = session.remove("idToken");

5 session.remove("accessToken");

6 cache.remove(authSupport.cacheKey(idToken));

7 return "ignoreThisValue";

8 }).map(id -> redirect(routes.AuthController.logIn()));

9 }

This is a lot of code, but authentication is now handled. We now have a way to log in, and a way to retrieve the user details from Auth0. This controller needs to be exposed in the routes file, and this also provides a nice overview to see what we’ve achieved.

1 GET /logIn be.objectify.whale.controllers.AuthController.logIn()

2 GET /callback be.objectify.whale.controllers.AuthController.callback(code: play.libs.F.O\

3 ption[String], state: play.libs.F.Option[String])

4 GET /logOut be.objectify.whale.controllers.AuthController.logOut()

5 GET /denied be.objectify.whale.controllers.AuthController.denied()

Now we have a /logIn route, that means you can have an explicit link to log in from your application. The one thing remaining to do is to have the log-in view displayed automatically when authorization fails.

The DeadboltHandler

There are only two methods that are required for this example to work. getSubject will retrieve the subject from the cache, and onAuthFailure will handle things as discussed above.

1 @Override

2 public F.Promise<Optional<Subject>> getSubject(final Http.Context context) {

3 return F.Promise.promise(() -> Optional.ofNullable(cache.get(authSupport.cacheKey(cont\

4 ext.session().get("idToken")))));

5 }

6

7 @Override

8 public F.Promise<Result> onAuthFailure(final Http.Context context,

9 final String s) {

10 return getSubject(context)

11 .map(maybeSubject ->

12 maybeSubject.map(subject -> Optional.of((User)subject))

13 .map(user ->

14 new F.Tuple<>(true,

15 denied.render(user)))

16 .orElseGet(() ->

17 new F.Tuple<>(false,

18 login.render(clientId,

19 domain,

20 redirectUri))))

21 .map(subjectPresentAndContent ->

22 subjectPresentAndContent._1

23 ? Results.forbidden(subjectPresentAndContent._2)

24 : Results.unauthorized(subjectPresentAndContent._2));

25 }

Improvements

This is a very simple example, but it demonstrates how easily it is to use event-driven behaviour and third-party identity management. There is one major problem, however, and you have until the end of this sentence to figure out what it is.

When the subject attributes are retrieved from Auth0, the resulting User object is cached for an arbitrary time - 15 minutes, in this case. With the implementation of DeadboltHandler given above, once that 15 minutes have passed the user will need to re-authenticate. However, it’s possible their authenticate period on Auth0 is still valid and so we’re placing an unnecessary burden on the end user. A simple improvement would be to attempt retrieval of the user attributes from DeadboltHandler#getSubject when the cache doesn’t contain the user.

It’s also possible to store meta data in Auth0, and so you can represent your roles and permissions there and bind them into local models when retrieving the subject’s attributes.