4. Prophetic Canonization Illustrated in the New Testament

The authoritative teachers sent forth by Christ to found his church, carried with them, as their most precious possession, a body of divine Scriptures, which they imposed on the church that they founded as its code of law… The Christian Church was never without a ‘Bible’ or a ‘canon.’

– Benjamin B. Warfield

The New Testament builds on the Old Testament; it does not replace the Old Testament

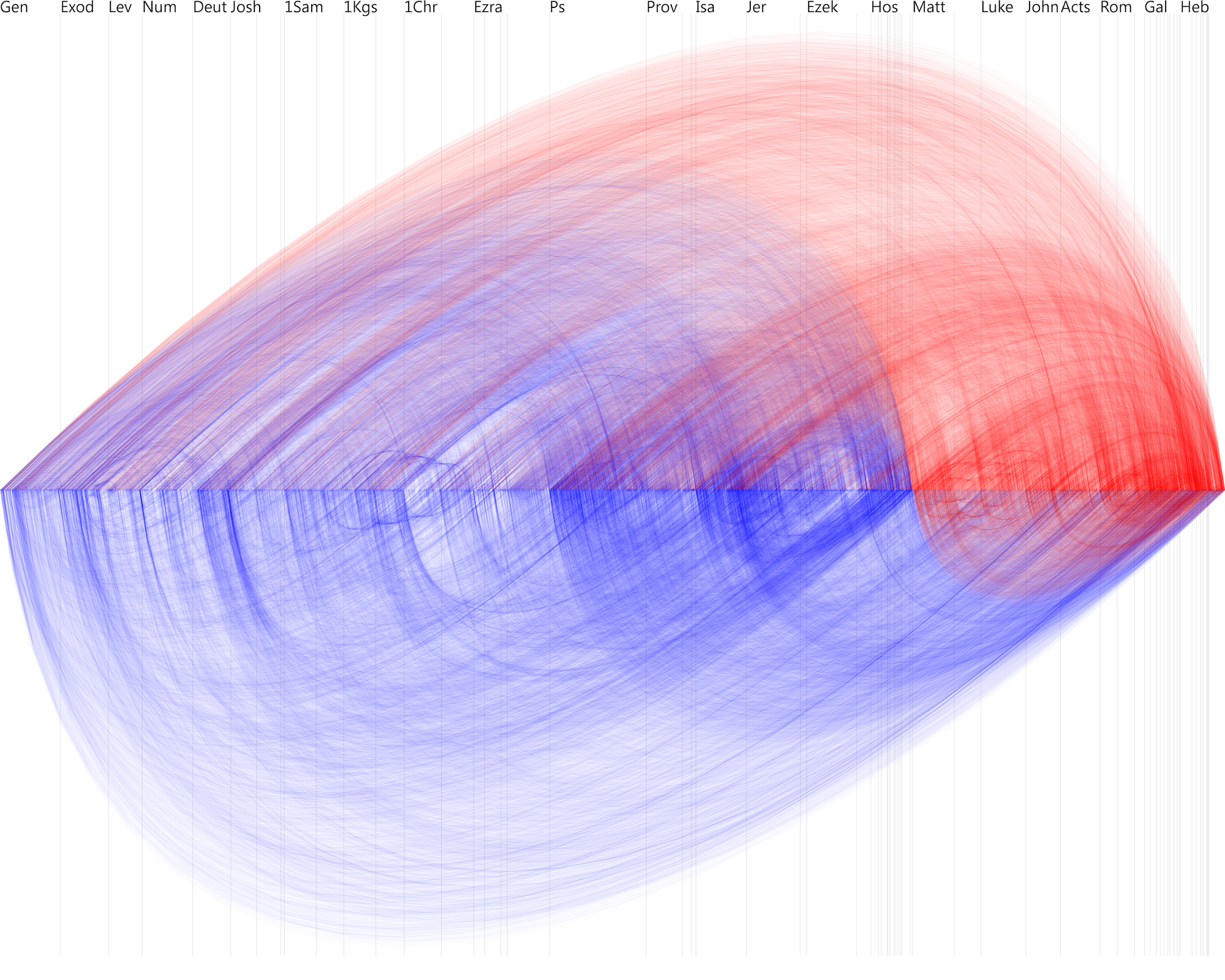

Many Christians reject the Old Testament as being irrelevant to our own culture, but when Paul deals with the sufficiency of Scripture (2 Tim. 3:16-17), it was precisely the Old Testament Scripture which he was talking about (see v. 15). Nor did he pick and choose, but said that “all Scripture is… profitable” (2 Tim. 3:16). The Bible of the early church (before the New Testament was written) was the Old Testament,96 and the apostles constantly proved their doctrines from its pages (Acts 17:2,11; 18:28; etc.). When the New Testament was written, it cited the Old Testament as authoritative more than 1600 times and had several thousand more allusions to the Old Testament.97 As we will shortly see, the Old Testament anticipated and depended upon the New Testament in ways that make the two Testaments inseparably linked. It is safe to say that one cannot understand the New Testament without seeing the Old Testament as being part of the authoritative canon of Scripture. Indeed, the two Testaments are inseparably bound together as one tightly woven fabric as is so well illustrated by the following graphic of 340,000 cross-references between books of the Bible.98

The New Testament did not replace the Old Testament canon, but was added to it. The Old Testament canon was called “the law and the prophets” (Mt. 5:17; 7:12; 11:13; 22:40; Luke 16:16,29,31; 24:27; John 1:45; Acts 13:15; 24:14; 26:22; 28:23; etc.). Christ Himself said that “until heaven and earth passes away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass away from the Law” (Matt. 5:18), and He went on to insist that even the least of the Old Testament commandments continued to be binding (v. 19). Without the Old Testament, we do not have a complete blueprint for any area of life. The New Testament was designed to fill out the Old Testament, not to replace it (Matt. 4:4; 5:17-19; 2 Tim. 3:15-17; Romans 15:4; Psalm 119:160; etc.).

Likewise, the Old Testament is not complete without the New Testament. God revealed to the Old Testament saints that the developing Old Testament canon was being crafted for the New Covenant age (1 Pet. 1:12). “And all these things happened to them as examples, and they were written for our admonition, upon whom the ends of the ages have come” (1 Cor. 10:11). If the Old Testament was being crafted with an eye to a completed canon in the New Testament, then we would expect that the Old Testament would speak about this completion process, and it does! We will spend an entire chapter discussing this later. Isaiah 8:16-20, Daniel 9:24, and other passages prophesied the closing of the canon and the complete cessation of all inspired prophecy in AD 70.

More to the point, the Old Testament looked forward to the coming of the Messiah, who would be the Prophet of all prophets (Deut. 18:18ff.). This Messiah would be the culmination of progressive revelation and thus would come at “the consummation of the ages” (Heb. 9:26 NASB), “the fullness of the time” (Gal. 4:4), “the ends of the ages” (1 Cor. 10:11), and “these last times” (1 Pet. 1:20). Christ’s words and acts formed the central core for both Testaments. As Hebrews 1:1-2 words it, “God, who at various times and in various ways spoke in time past to the fathers by the prophets, has in these last days spoken to us by His Son, whom He has appointed heir of all things.” Ned Stonehouse says, “The divine messiahship of Jesus is then the basic fact behind the formation of the New Testament.”99

The oral “tradition” (deposit) given from Father to Son, from Son to apostles, and from apostles to prophets and church has exactly the same content as Scripture

If the Messiah, Jesus Christ, was to be the Prophet of all prophets, how did He speak to the church? He wrote no books Himself. The New Testament speaks of itself as being a one-time deposit (παράδοσιν) of inspired teaching. The word for “deposit” is usually translated as “tradition” and represents something handed down with authority. These inspired “traditions” stand in sharp contrast with the traditions of man (Matt. 15:2-3,6; Mark 7:3,8-9,13; Gal. 2:8). This deposit was first delivered from the Father to the Messiah:

All things have been delivered (παράδωσει) to Me by My Father, and no one knows the Son except the Father. Nor does anyone know the Father except the Son, and the one to whom the Son wills to reveal Him. (Matt. 11:27; see Luke 10:22)

Christ in turn “revealed” the “all-things” deposit to the apostles (Matt. 11:27; John 14:26; 16:12-13; 15:15; 20:21-23). By prophetic revelation the apostles gave this “tradition” of truths to the church (Luke 10:22; 1 Cor. 11:2,23; 15:3; 2 Thes. 2:15; 3:6; 1 Pet. 2:21; Jude 3). Initially the “all-things” deposit (John 15:26-27) was given by an oral apostolic witness (Acts 1:21-22; 2 Thes. 2:14; etc). The Spirit reminded them of “all things” in this deposit of truth as they wrote the Scriptures (John 14:25-26; 16:13-15). Anything beyond the “all things” that Christ authorized was part of the secret things of God (cf. Deut 29:29), and even if the apostles knew some of those secrets (as, for example, Paul’s vision in 2 Corinthians 12) they were forbidden to reveal them to the church since they are “inexpressible words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter” (2 Cor. 12:4). From the time the first New Testament book was added to the Canon till the book of Revelation was written, only those things were included which would be useful and necessary for the community that would use the finished canon.

Paul was the “last” of these apostolic witnesses (1 Cor. 15:7-8), and as an apostle “born out of due time” (1 Cor. 15:8), had to receive His commission and the “all things” from Christ as well. Thus he went to Arabia for three years to be taught of Christ (Gal. 1:16-18) and over and over again reminded his hearers that the things he taught were received (παράδωσει) from Christ and not from man (1 Cor. 11:1,23; 15:3; Gal. 1:12,16-18). This makes Christ the final revelation of God to man. This is why Hebrews 1 says, “God who at various times and in various ways spoke in time past to the fathers by the prophets, has in these last days spoken to us by His Son.” The final deposit for the canon was completely made in Jesus Christ. Even the non-apostolic prophets Luke, James, and Jude wrote from this “all-things” deposit that the apostles had already given to the church. For example, Jude says:

Beloved, while I was very diligent to write to you concerning our common salvation, I found it necessary to write to you exhorting you to contend earnestly for the faith which was once for all delivered (παραδοθείση) to the saints. (Jude 3)

If this body of truth has already been “once for all delivered” in the first century, it logically precludes the deliverance of apostolic tradition in later periods of church history. As F. F. Bruce worded it,

Therefore, all claims to convey an additional revelation… are false claims… whether these claims are embodied in books which aim at superseding or supplementing the Bible, or take the form of extra-Biblical traditions which are promulgated as dogmas by ecclesiastical authority.100

This means that New Testament “tradition” is utterly different from the “Tradition” of Rome and Eastern Orthodoxy, both of which contain many things not found in Scripture. The oral teachings of the apostles were the infallible transmission of the “all-things” tradition with no admixture by man. Thus Paul could say, “when you received the word of God which you heard from us, you welcomed it not as the word of men, but as it is in truth, the word of God, which also effectively works in you who believe” (1 Thes. 2:13). Likewise the written Scriptures were the infallible transmission of the “all-things” tradition. Paul said, “Therefore, brethren, stand fast and hold the traditions which you were taught, whether by word or epistle” (2 Thes. 2:14).

The early church did not see apostolic tradition as in any way going beyond the 27 books of the New Testament.101 They saw the New Testament as being the written form of the “all-things” tradition and totally sufficient for faith and practice.102 The church was commanded to hold fast to the oral apostolic teachings, but the only way they could do so (since those being told to do so were not inspired) was to hold fast to the written teachings of the New Testament. Thus, though Paul imposes “tradition” on the churches (1 Cor. 15:3-4), he twice makes clear that the tradition is “according to the Scriptures” (see verse 4 and 5). Paul was not opposed to tradition (2 Thes. 2:15; 3:6) since tradition is simply apostolic teaching. What he was opposed to was “the tradition of men” (Col. 2:8). Everything Paul taught could be proved from the Scriptures (Acts 17:11) and he insisted that the church “not think beyond what is written” (1 Cor. 4:6). For both the apostles and the early church, tradition was a once-for-all deposit of truth given from the Father to Jesus, from Jesus to the apostles, from the apostles to the prophets and church, and then finally this orally transmitted deposit of inspired prophecy was inscripturated in the New Testament canon. Since God’s tradition was apostolic, we have yet another reason not to expect Scriptures to be written beyond the age of the apostles. In chapters 6 and 7, we will give definitive evidence that the canon was closed before AD 70, thus ruling out all so-called “New Testament apocrypha.”

This Protestant concept of Tradition also rules out the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox insistence that Tradition is broader and greater than Scripture. The reality is that apostolic doctrine flowed out of the Old Testament, and everything the apostles taught could be found in the Old Testament (Acts 26:22; 17:11). This is why every word of oral Tradition that the apostle Paul gave was rightfully tested for its truthfulness against the Old Testament Scriptures (Acts 17:11), and he didn’t teach anything that was not already anticipated in the Old Testament Scriptures (Acts 26:22). Likewise, 2 Timothy 3:14-17 shows that the Old Testament Scriptures (see v. 15) are sufficient to make the man of God “complete, thoroughly equipped for every good work” (v. 17). If there is even one good work that Tradition calls us to that we can’t find in the Old Testament, then Paul was wrong in that statement. So it is clear that Old Testament Scripture produced Tradition, and the New Testament records that Tradition (apostolic doctrine) in its entirety. We will later see that this was the view of the early church.

How this deposit of Christ was written down in canonical books

Instant canonization illustrated in the Pauline and Petrine epistles

The internal evidence shows that the New Testament treated itself as Scripture the moment it was being written in exactly the same way that the Old Testament treated itself as being Scripture the moment it was written. As already noted, Paul quotes Deuteronomy 25:4 and Luke 10:7 as both being equally Scripture and both being equally authoritative when he declares:

For the Scripture says, “You shall not muzzle an ox while it treads out the grain,” and “The laborer is worthy of his wages.” (1 Tim. 5:18)

To quote Luke as “Scripture” so soon after Luke was written completely contradicts the notion that the church later canonized Luke.103 This quote assumes as a truism that the Gospel of Luke was already universally seen as part of the canon when Paul wrote the book of 1 Timothy (AD 65). Likewise, in AD 66, 2 Peter 3:15-16 speaks of Paul’s writings as “Scriptures” and declares “all his epistles” as being canonical with “the rest of the Scriptures.” The “all” indicates that Peter considered not only Paul’s oldest writings (1 and 2 Thessalonians) to be Scripture, but also 2 Timothy, an epistle written earlier in the same year that 2 Peter was written (AD 66).

Nor should it be assumed that Peter canonized Paul’s writings. Long before Peter treated all Paul’s writings as Scripture, Paul insisted that the church treat his writings as God’s word - once in AD 51 (1 Thes. 2:13; 4:15) and again in AD 54 (1 Cor. 14:37). This illustrates that canonization was a prophetic function of the inspired writer himself. Even as the words were coming off of Paul’s pen and onto the writing material, Paul insisted that the prophets in Corinth (if they were true prophets) acknowledge that the words he was writing in 1 Corinthians 14 were “the commandments of the Lord” (v. 37). This means that the very moment Paul was penning 1 Corinthians 14, Paul was treating those words as canonical. This parallels our discussion of Moses and Isaiah in chapter 3.

Instant canonization illustrated in the book of Revelation

The context of inscripturated canon

This is also seen in the last book of the Bible, Revelation. One of the major themes of the book of Revelation is the opening of the already existing biblical canon by Christ (5:2-7,9) and the subsequent closing of the canon of Scripture in AD 70 (10:7) after the last book of the Bible had been written (10:8-11; 22:7,9-10,18-19). The vision of the big scroll of Revelation 5 shows that the sealed canon of the Old Testament (Rev. 5:3)104 continues to be the prophetic basis for judgments upon both Israel and Gentile nations (Rev. 6ff.).105 That canon had been closed and could not be opened until the Lamb of God Himself authorized its opening (Rev. 6:2-7,9). Once that canon was re-opened after the ascension of Christ in AD 30 (Rev. 5:5-7,9), Christ sent forth numerous prophets (10:7,11; 11:1-13,18; 16:16; 18:20,24; 19:10; 22:6-7,9-19) who witnessed to His revelation until such time as the New Testament canon would be finished (10:7 Greek). Though these prophets were killed, they formed the revelational foundation for the New Testament church.

John’s own prophetic witness to the truth (cf. Rev. 1:2) involved the writing of the little scroll of Revelation (10:8-11). The Greek word for the “little scroll” is βιβλιδάριον (cf. Rev. 10:8-10 in MT and 10:9-10 in USB) and is distinguished from the βιβλίον or big scroll of Revelation 5. The βιβλιδάριον is the book of Revelation and the βιβλίον is the growing canon of Scripture. John’s eating of the little scroll parallels Ezekiel’s eating of the little scroll in Ezekiel 2-3 on many levels.106 The vision showed that before either prophet could prophesy the contents of his prophetic volume, he would need to be inspired (likened to eating an already written book). What was eaten by both prophets was the content of their respective books that were to be added to the canon. In Ezekiel 2:9 the prophet is given what is called the “scroll of a book.” In other words, the whole book is not handed to Ezekiel, but only one scroll of that “book” or collection of scrolls (migilath sepher - ְמְגִלַּת־סֵֽפֶר). The Jewish translators of the Septuagint render that Hebrew expression as κεφαλὶς βιβλίου, or “volume of the book.” So Ezekiel’s prophecies comprise one of the volumes of a much larger book - the canon. In much the same way, the “little book” of Revelation (the βιβλιδάριον) is the last volume or scroll of this growing book of canon.

What John writes is Scripture the moment he writes it

When this distinction between βιβλιδάριον (little book) and βιβλίον (canon) is kept in mind, then it is clear that the moment John wrote down his prophecies, they were being written into the canon of Scripture. Just as Joshua and Samuel wrote into the book of the law (the canon) John is commanded, “What you see, write in a book (βιβλίον or canon)” (Rev. 1:11). In Revelation 22:18-19, God does not just forbid adding to or subtracting from the smaller scroll of Revelation. On the contrary, the canon itself was being closed:

For I testify to everyone who hears the words of the prophecy of this book (βιβλίον or canon): If anyone adds to these things, God will add to him the plagues that are written in this book (βιβλίον or canon); and if anyone takes away from the words of the book (βιβλίον or canon) of this prophecy, God shall take away his part from the Book of Life, from the holy city, and from the things which are written in this book (βιβλίον or canon). (Revelation 22:18-19)

It is significant that John did not use the word that described the smaller scroll of Revelation when giving these warnings. He used the word βιβλίον. Certainly John wrote all of his prophetic words into the scroll of Revelation as well (Rev. 10:8-11), but in doing so he was writing them immediately into the canon of Scripture. This is confirmed by the fact that his words did not take on Scriptural authority only after the church declared them to be Scripture. John’s written words had immediate Scriptural (“written”) authority (Rev. 1:13,19; 2:1,8,12,18; 3:1,7,14; 14:13; 19:9). As we have seen, this is consistent with the way all the Old and New Testament prophets had been writing the previous books of the Bible.

A later chapter on the cessation of prophecy will dig into the exegetical details of canon in the book of Revelation in much more detail. This chapter has sought to demonstrate the immediate canonization of all Scripture, from Genesis to Revelation the moment it was written. The reason Revelation is Scripture is because a prophet (John is characterized as a prophet and his writings as prophecy in Rev. 1:3; 10:11; 19:10; 22:6-7,9-10,18-19) canonized the prophecies as they were being written (Rev 1:11; 22:18-19). Revelation 10-11 anticipated the imminent time (Rev. 10:7) when both the canon and all other prophetic revelation would cease. So Revelation 10 is preoccupied with the imminent ending of prophetic Scripture and Revelation 11 is preoccupied with the imminent ending of oral prophecies (with the death of the last two prophets).107