5. Apocrypha Written Before Christ?

Any inspired writer was ipso facto a prophet.

– F.F. Bruce

For the children of Israel shall abide many days without king or prince, without sacrifice or sacred pillar, without ephod or teraphim.

– Hosea 3:4

‘Behold the days are coming,’ says the LORD GOD, ‘that I will send a famine on the land, not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water, but of hearing the words of the LORD. They shall wander from sea to sea and from north to east; they shall run to and fro, seeking the word of the LORD, but shall not find it.’

– Amos 8:11-14

Having established the immediate inscripturation of the 66 books of the Protestant canon, what are we to make of the apocryphal108 and pseudepigraphal109 books written in the three centuries prior to Christ? Some non-Protestant churches accept some or all of the apocryphal books and some cults even accept some pseudepigraphal books. This chapter will seek to clearly show why no “Old Testament apocryphal book” can possibly be part of Scripture. Though there are some additional criteria people have used to rule out these books,110 the Bible’s own claim that there would be a complete cessation of prophecy during the four hundred years prior to Messiah is sufficient evidence to rule out all non-prophetic literature. As William Whitaker worded it,

The entire syllogism is this. All canonical books of the Old Testament were written by prophets: none of these books was written by a prophet: therefore none of these books is canonical.111

In light of the information that will be presented in this chapter, it is significant that no apocryphal book claims to be written by a prophet.112 Some of the authors even deny that they are inspired prophets.113 Why would non-Protestants canonize such books when their own Apocrypha’s internal testimony is against their being prophetic?

It was an axiom among Jews that all Scripture was prophetic. Second, it was an axiom among Jews that the Scripture foretold the cessation of all prophecy from 400 BC until the Messiah should arise as the Great Prophet. If these two claims can be backed up by Scripture, then 100% of the apocrypha found in the Roman Catholic canon can be automatically ruled out. We will examine both of these statements in more detail.

All canonical Scripture was considered to be prophetic

According to Jews, every Old Testament book was considered to have been written by a prophet.114 Thus, Josephus distinguished between the historical writings that were canonical and those that were not canonical based upon whether they were prophetic or not.115 The Jewish Encyclopedia summarizes the view of Jews through history when it says, “Every Biblical book was said to have been written by a prophet… There is thus an unbroken chain of prophets from Moses to Malachi.”116 F. F. Bruce summarizes the conclusive evidence by saying, “Any inspired writer was ipso facto a prophet.”117 As an ad hominem argument this information is enough to prove that the apocrypha were not treated as Scripture in the first century.

More importantly, the Scriptures agree. The Bible calls itself “the prophetic Scriptures” (Rom. 16:26). If every portion of Scripture was not written by a prophet, that would be a difficult statement to understand. 2 Peter 1:20-22 claims that the entire Scripture was prophetic and therefore reliable, since “prophecy never came by the will of man, but holy men of God spoke as they were moved by the Holy Spirit.” Hebrews 1:1 contrasts the finality of revelation that came through Jesus in the New Covenant with the revelation that came through a variety of means and ways in the Old Testament, and describes that entire Old Testament corpus as God speaking “to the fathers by the prophets.” Indeed, the whole Old Testament is referred to as “the prophets” (Luke 24:25,27; John 6:45; Heb. 1:1) or “the Scriptures of the prophets” (Matt. 26:56), or God speaking “through His prophets in the Holy Scriptures” (Rom. 1:2).

Nor is this view contradicted by the Jewish two-fold division of the Old Testament. When the New Testament divides the Old Testament Scriptures into “the law and the prophets” (Matt. 7:12; 22:40; 16:16; John 1:45; Acts 13:15; 24:14; 28:23; Rom. 3:21) or “Moses and the prophets” (Luke 16:29,31; cf. 24:27,44; John 1:45; Acts 26:22; 28:23), it is not claiming that Moses was not one of the prophets. He is clearly called a prophet (Deut. 34:10; Acts 3:22; 7:37). This is simply a division Jews used to distinguish the foundational law found in the Pentateuch from the application and enforcement of the law by all the rest of the Old Testament prophets. It is crystal clear that the two-fold division of the Old Testament into “Moses and all the Prophets” encompassed “all the Scriptures” (Luke 24:27) and therefore all the Old Testament Scriptures were given by prophets.

Nor is this thesis (that only a prophet could write an Old Testament canonical book) contradicted by the three-fold division of “the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms” (Luke 24:44). This is clear since the authors of the Psalms are called prophets. For example, Asaph wrote twelve Psalms (Psalm 50, 73-83) and he is clearly called a prophet (2 Chron. 29:30; Matt. 13:35). David has all the descriptors of a prophet given to him118 because his inspired writings were the very words of God - “The Spirit of the LORD spoke by me, and His word was on my tongue. The God of Israel said, the Rock of Israel spoke to me” (2 Sam. 23:2-3). More to the point, the Psalms are quoted as being the words of a prophet (Ps. 132:11 quoted in Acts 2:30), equivalent to the law (see Psalm 82:6 quoted in John 10:34), as being the very words of the Holy Spirit (e.g., see Psalm 95:7-11 quoted as words of the Spirit in Heb. 3:7-11), and as being Scripture (Ps. 118:22-23 quoted in Matt. 21:42). Thus, the three-fold division is not a denial of the prophetic authorship of the Psalms and Proverbs, but is simply a convenient literary division of the Old Testament.

We will have much more to say about the foundational role of prophets in even the New Testament Scriptures in a later chapter, but for now it is sufficient to notice that the Old Testament Scriptures were prophetical. If, therefore, prophecy ceased in 400 BC (as we will shortly demonstrate), then by definition the apocrypha cannot be Scripture since it was written after 400 BC and before the coming of Christ.

All prophecy ceased in 400 BC

This was the standard Jewish view of Christ’s day

Did all prophecy really cease between 400 BC and the coming of Christ? This was certainly the view of the Jews in the first century. As already stated, it was an axiomatic principle for Jews that prophecy ceased with the writing of Malachi and 2 Chronicles. Fisher summarizes Josephus’ views by saying that he believed “all the inspired books were completed between the time of Moses and Artaxerxes, successor to Esther’s husband Xerxes, at which time the prophetic succession ceased, no one daring to add, take away, or alter the contents of those writings ever after.”119 Josephus’ view was the uniform Jewish view of the time120 and before.121 Even the Babylonian Talmud expresses this view in several places.122

Hosea’s witness

Hosea prophesied that following the exile there would be a long period without prophetic revelation.

So I bought her for myself for fifteen shekels of silver, and one and one-half homers of barley. And I said to her, “You shall stay with me many days; you shall not play the harlot, nor shall you have a man—so, too, will I be toward you.” For the children of Israel shall abide many days without king or prince, without sacrifice or sacred pillar, without ephod or teraphim. Afterward the children of Israel shall return and seek the LORD their God and David their king. They shall fear the LORD and His goodness in the latter days. (Hosea 3:2-5)

This inspired prophecy foretold six things that Israel would be without for a long period of time. What period is it referring to?

Context = intertestimental period

That this is a reference to the inter-testamental period can be seen from several exegetical considerations.

First, what happens “afterward” in verse 5 is Messianic, since seeking Yehovah is equivalent to seeking “David their king.” It is not simply seeking a son of David, but it is a person who is both Yehovah and “David.”123 So verse 5 must be anchored in the first century AD.

Second, Gomer leaving Hosea symbolizes northern Israel being cast into exile in 722 BC because of her unfaithfulness (v. 1). So verse 1 should be anchored no earlier than 722 BC.

Third, the whole point of Hosea restoring Gomer to himself and ensuring that she remain faithful to him was a prediction of God restoring the scattered tribes of Israel to the land and ensuring that they remain faithful to Him. When did the tribes get restored? The restoration occurred in the books of Ezra, Nehemiah, and the post-exilic prophets. So verse 2 should be anchored in approximately 537 BC.

Fourth, Hosea speaks of Gomer being faithful to Hosea for “many days” (v. 3) as a prophetic symbol of Israel’s faithfulness to God for “many days” (v. 4). The fact that Zechariah (520 BC and after) prophesies against people who use teraphim124 (Zech. 10:2), shows that the period being anticipated as without teraphim must be somewhat later than Zechariah’s prophecy. Was there a time when at least outwardly, the use of idols was completely rejected by Israel? Yes. The restored Israel did remain faithful to God for most of the time between 400 and 5/4 BC.

So verse 4 has to occur some time after the post-exilic prophets and sometime before 5/4 BC (when Jesus was born).125 This window of time is what has been traditionally spoken of as the “four hundred years of silence.”126

Cessation of revelation from 400 BC - 5/4 BC

Hosea 3:4 says that there are six things that Israel would be without during these four hundred years, and they are grouped into three sets of couplets:

- Neither king nor prince - contrasted with Christ’s office of King

- Neither pagan worship nor pagan idols - contrasted with Christ’s office of Priest

- Neither divine revelation or demonic revelation - contrasted with Christ’s office of Prophet

Were these three couplets fulfilled during the period of 400-5/4 BC? Yes. Each one of these couplets stands as a wonderful contrast to Jesus being the final King, Priest, and Prophet. Let’s consider the fulfillment of each one.

It is a fact of history that Israel was “without king or prince” from the line of David until the final representative of David (Jesus - see Hosea 3:5) appeared on the scene in 5/4 BC. Commentators point out that the Messiah is called “David,” which would be impossible if He was not from the line of David. So this sets up a strong contrast between the Davidic kings and those Hasmonean rulers that were clearly not Davidic. The Hasmoneans (or Maccabbees) were from the tribe of Levi and were never considered to be from the tribe of Judah or from the line of David. Thus, they could never qualify as true kings of Israel or even princes of Israel. In contrast, Jesus is over and over said to be a son of David who sits on the throne of David. The Hasmoneans acted more like the judges in the book of Judges. So this was a period in which God alone was seen as King and lawgiver. The Intertestamental “Judges” simply implemented Biblical law, and as can be seen from 1 Maccabees, were faithful in doing so.

It is a fact of history that Israel was “without sacrifice or sacred pillar” to false gods during this same period.127 As David Baron words it,

…since then [the exile] they have manifested the greatest abhorrence of everything bearing the remotest resemblance to idolatry. Of course there is another kind of idolatry: there are the ‘idols of the heart’ (Ezek. xiv. 4), which are quite as hateful in the sight of God as images of wood and stone, but with this our passage does not deal.128

Why would Jesus as the final Priest be contrasted with pagan worship rather than with the priests of Israel? I believe it is because these couplets are dealing with things that Israel was “without” in order to anticipate the need for a Messiah who would encompass all three offices. Since Israel was not without a priesthood from 400-5/4 BC, the only thing that could be contrasted with is pagan worship. That pagan worship is in view can be seen from the fact that the “sacred pillar” is always seen as idolatrous (Ex. 23:24; 34:13; Lev. 26:1; etc.). God is not denigrating the intertestamental Jews. They were foretold to be saints (Dan. 7:18) who would be mighty in exploits because they knew their God (Dan. 11:32).

The last couplet was also fulfilled during the years of AD 400-5/4 BC. Israel was clearly “without ephod or teraphim” during the same period. Both of these articles were used to receive revelation, and are being contrasted with Jesus being the final Prophet. The ephod was a godly source of revelation (Numb. 27:21) and the teraphim was an unauthorized and ungodly source of revelation from demons (2 Kings 23:24; Ezek. 21:21).129

The ephod was a special garment worn by the High Priest that had stones embedded in it (Ex. 28:12, 39:7,21) including the Urim and Thumim (Ex. 28:30; Lev. 8:8), which somehow gave detailed prophetic guidance from the Lord (see 1 Sam. 23:9-12; 30:7-8 for examples). The post-exilic community did not have access to the Urim and Thumim (Ezra 2:61-63).130 That community was waiting for a priest to hopefully find those articles, but they apparently never did get discovered. The Talmud states that the Urim and the Thummim and the spirit of prophecy were among the five things missing from the Second Temple.131

As to the idolatrous teraphim, we have already noted that the Hasmoneans completely eliminated idolatry even among pagans in the area. Bleich says,

But at the time of the second temple, in the days of the Hasmoneans, they rose again to a great degree, and rooted out the worship of idols. Then all those who came from the Babylonian exile recognized and knew that the Lord is God.132

So Hosea 3:4 is a text that anticipates not only an interregnum133 but also a long interruption of prophetic revelation. It might be thought that this was due to unfaithfulness on the part of God’s people, but Scripture denies that. Daniel says of these future (to him) people: “the people who know their God shall be strong, and carry out great exploits” (Dan. 11:32). This means that it was possible for these Maccabees to “know” God without ongoing prophetic revelation because they clung to what Daniel elsewhere describes as the “Scripture of Truth” (Dan. 10:1). The Maccabees anticipated a time when the Messiah would come and when “a prophet should arise” (I Macc. 4:46; cf. 9:27; 14:41), but until that time they stuck to the Scriptures alone. The reason is clear: if there were no prophets to write Scripture, then the apocryphal books that were written during that time could not be Scripture.

Amos’ witness

Amos provides us clear instruction that completely rules out any form of prophecy whatsoever in the years 400-5/4 BC. Amos says,

‘Behold the days are coming,’ says the LORD GOD, ‘that I will send a famine on the land, not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water, but of hearing the words of the LORD. They shall wander from sea to sea and from north to east; they shall run to and fro, seeking the word of the LORD, but shall not find it.’ (Amos 8:11-14)

Hints of the timing of this absence of prophecy

Amos chapter 8 comes historically after chapter 7

The sequence of these chapters makes it clear that the subject matter of 8:11-12 occurs during the same period that Hosea 3:4 did, namely 400-5/4 BC. Much of the message of Amos deals with the imminent scattering of the northern tribes by Assyria. Their predicted exile happened in 722 BC. However, Amos also has concerns with the sins of the southern tribes (see explicit references to Judah in 2:4-5). It is my belief that chapter 7 ends with the exile of the northern tribes in AD 722. Chapter 8 moves on to Judah’s own sins and predicts a similar exile of Judah under Nebuchadnezzar in 607 BC. Chapter 9 then moves on to an even more distant exile of all Israel in AD 70, followed by a building of the New Covenant134 tabernacle of David among the Gentiles (9:11-12) followed at some point by the millennial success of the Great Commission (9:13-15).

That is the broad sequence of Amos 7-9. We will now begin to examine the timing of Amos 8:11-12 in more detail. That Judah is in view in chapter 8 can be seen from the fact that judgment is connected with the temple (v. 2), Sabbath observance is at least nominally followed (v. 5 - not true of the north), and that people are keeping the temple feasts (v. 10 - חַג). Commentaries sometimes slide over the indicators that a switch to Judah has occurred. The confusion often comes from the mention of Samaria in verse 14, but we will see that this reference actually fits a post-exilic time period far better.

8:1-10 is 607 BC and 8:11-12 is after 607 BC

The next hint about time is seen in the contrast between an imminent judgment that was already upon them and a distant prophecy of what will happen in the days to come. Verse 2 says, “The end has come upon My people Israel; I will not pass by them anymore…” This indicates an imminent destruction of temple and people (v. 3) that will not wait any longer. In contrast, the first phrase of verse 11 says, “Behold, the days are coming…” Since the judgment of verses 1-10 was already upon them, the days of verses 11-12 must be subsequent to Judah’s exile in verses 9-10. Of course, the flow of the text itself would indicate that. Since judgment on the temple (v. 3) and an ending of temple festivals (v. 10 - חַג) is in view, verses 1-10 should be seen as referring to the exile of Israel in 607 BC.

Ezekiel-Malachi is non-stop prophetic activity, therefore 8:11-12 comes after Malachi.

Since 607-400 BC had non-stop giving of prophecies by exilic and post-exilic prophets from Ezekiel to Malachi, and since verses 11-12 predict a complete absence of prophecy (vv. 11-12), verses 11-12 must come after the last post-exilic prophet wrote his prophecies in 400 BC.

Samaria and the tribe of Dan were both still in existence (v. 13)

However, the fulfillment cannot be in our distant future because Samaria and the tribe of Dan are still in existence when this prophecy is fulfilled, something impossible in our day. There are Samaritans, but no Samaria today. Likewise, there are no tribal distinctions among Jews anymore. As Fred Gilbert words it,

For nearly two thousand years there have been no tribal distinctions. The tribe of Judah has passed away, and has lost its distinctively tribal standard ever since the destruction of the temple at Jerusalem, and since then the Jews have been scattered. Since then, no Jew can really prove to which tribe he belongs.135

During the years of 400-5/4 BC, Samaria and Dan did exist. Samaria had a mongrel religion that stood in opposition to the true Scriptures. The Samaritan religion started in 2 Kings 17:24-41 as a mixture of paganism and the law of God. The syncretism they engaged in is “the sin of Samaria.” The Samaritans took over the territory of Dan, also referred to in verse 14. Because it was a false religion, verse 14 records them saying, “As your god lives, O Dan!” Dan and Samaria are implied to be in a hostile relationship to the true religion of the Bible. History tells us that this was indeed the case. There was constant animosity between the Jews and the Samaritans, beginning in Nehemiah 6:1-14 and continuing into the time of Jesus (cf. John 4:6-26; 8:48).

All of the details perfectly fit the time period of 400-5/4 BC, and some of the details can only fit that period.

How Amos 8:11-12 rules out the existence of any prophecy in any form during the years 400-5/4 BC

It mentions a total absence of the word of the Lord.

First, unlike the days of Eli when “the word of the LORD was rare in those days” and when “there was no widespread revelation” (1 Sam. 3:1), Amos predicts a time when there would be no revelation (“shall not find it”). Even if one were to misunderstand this as a tragic withholding of prophecy (i.e., as a judgment), the fact should not be missed that there was a total absence of “hearing the words of the LORD.” Even those seeking revelation diligently would not find it. Neither the godly nor the ungodly had prophetic insight.

God Himself sends this absence of prophecy

Second, it was God Himself who sent the famine of revelation. God says, “I will send a famine… of hearing the words of the LORD.” God has the freedom to give or to not give revelation, and we cannot bind His hand if He has so chosen. The concept of cessation of prophecy is not a limitation of God. Rather it is God’s sovereign freedom to give or not to give. The question is not “What can God do?” but rather, “What has he chosen to do?” The accusation of many Romanists, Eastern Orthodox, and other Continuationists is that Cessationists are binding the hand of God. This passage (and others like it) is simply showing what our free God has chosen to do, not making us doubt what He can do. Some argue that the lack of prophecy is not because God is not speaking, but rather because we are not listening. This passage clearly shows that their failure to receive revelation was because of God’s lack of giving (“I will send a famine”).

The absence of prophecy is not because people fail to seek for it

Third, this absence of revelation was not because God’s people were failing to seek prophetic insight. Amos describes passionate searching for revelation: “They shall wander from sea to sea and from north to east; they shall run to and fro, seeking the word of the LORD, but shall not find it.” Once again, the cessation of revelation cannot be entirely blamed upon a lack of desire for prophecy.

The absence of prophecy is universal

Fourth, Amos speaks of a cessation of revelation that was universal. The phrase, “from sea to sea” is also used to describe the universal reign of the coming Messiah (see for example Psalm 72:8; Zech. 9:10; Mic. 7:12). Since the Mediterranean bordered Israel on the West, the phrase, “from north to east” would include all the other pagan lands to the north and east.136 The famine of revelation was everywhere in the world; it was universal.

This particular cessation of prophecy is temporary and not final

Fifth, it is admitted that the lack of revelation in this passage is framed in negative terms (“famine”) rather than positive terms (“no need for revelation”). Continuationists might argue that all Cessationism is a curse or a famine. This argument will be countered when we consider a command from God to no longer seek prophet or vision after 70 AD (see discussion of Isaiah 8 in the next chapter). For now it is helpful to note that prior to the time of Christ, revelation was not complete. God was preparing people to long for the coming of the Great Prophet, Jesus Christ. Cessationists too believe that there was need for more revelation after Malachi was written. There was every reason to seek for more from God and to long for more from God.

We have seen that both Hosea and Amos predicted a complete cessation of prophecy in the years 400-5/4 BC. Therefore, the apocrypha cannot be Scripture because all the apocrypha was written between 300 and 50 BC. Furthermore, none of the apocrypha in the Roman Catholic Bible make any claim to be prophetic (understandably so, since they were written after the age of the prophets). Geisler says that the apocryphal books

… lack any claim to divine inspiration… There is indeed a striking absence in the Apoc of the “thus saith the Lord” found hundreds of times in the prophetic books of the Hebrew canon. Indeed, there is neither an explicit nor implicit claim to inspiration in any of the apocryphal books.137

In the following paragraphs we will outline the apocrypha that is listed in each non-Protestant canon, then will date them, and using those dates will prove definitively that they are not canonical.

The previous information rules out 100% of the apocrypha of Rome, Eastern Orthodoxy, Coptic, and Ethiopic church

The different canons of non-Protestant churches

The Romanist canon

In 1546 (at the Council of Trent) Rome officially added the following books (or portions of books) to the canon: Tobit, Judith, the Greek additions to Esther, the Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Baruch, the Letter of Jeremiah, three Greek additions to Daniel (the Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews, Susanna, and Bel and the Dragon), and 1 and 2 Maccabees.

The Eastern Orthodox canons

The Greek Orthodox Church added 1 Esdras, the Prayer of Manasseh, Psalm 151, and 3 Maccabees to the books accepted by the Roman Catholic Church. The Slavonic (Russian) Orthodox Church adds to the Greek Orthodox canon the book of 2 Esdras, but designates 1 and 2 Esdras as 2 and 3 Esdras. Some Orthodox churches add the book of 4 Maccabees as well. The Armenian Bible includes the History of Joseph and Asenath and the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, and the New Testament included the Epistle of Corinthians to Paul and a Third Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians

The Coptic canon

The Coptic Church adds the two Epistles of Clement.

The Ethiopian canon

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church has the largest canon of all. To the apocryphal books found in the Septuagint Old Testament, it adds the following: Jubilees, 1 Enoch, and Joseph ben Gorion’s (Josippon’s) medieval history of the Jews and nations. To the 27 books of the New Testament they add eight additional texts: namely four sections of church order from a compilation called Sinodos, two sections from the Ethiopic Book of the Covenant, Ethiopic Clement, and Ethiopic Didascalia. It should be noted that for the New Testament they have a broader and a narrower canon. The narrower canon is identical to the Protestant and historic (true catholic) canon.

The apocrypha of ancient Greek manuscripts

It is important to note that though the ancient manuscript tradition clearly testifies to all of the books in the Protestant canon, no Uncial manuscript contains all the books of any non-Protestant tradition.

Vaticanus (B) contains 1 Esdras, Wisdom, Eccesiasticus/Sirach, Judith, Tobit, Baruch, and the Epistle of Jeremiah. Sinaiticus (א) contains Tobit, Judith, 1 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, Wisdom, and Ecclesiasticus/Sirach.

Alexandrinus (A) contains Baruch, Epistle of Jeremiah, Tobit, Judith, 1 Esdras, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus/Sirach, and Psalms of Solomon.

Only four apocryphal books are found common to all three of the earliest Greek manuscripts (Judith, Tobit, Wisdom, and Ecclesiasticus/Sirach), and, as Geisler words it, “No important Greek MS has the exact number of books accepted by Trent.”138 Aquila’s Greek translation of the Old Testament did not contain any apocrypha. Likewise, the fact that the Vulgate translation contains the apocrypha does not prove that the church of that era saw them as having canonical status any more than Protestant Bibles that contain the apocrypha prove that Protestants accept the apocrypha.

When Jerome translated the apocryphal books, “he was careful to indicate by Prefaces those books and parts of books not found in the Hebrew canon,”139 and he clearly taught that the apocrypha were not canonical and even to some degree dangerous.140

Names and dates of contested inter-testamental apocrypha and pseudepigrapha

When we date the apocrypha it becomes crystal clear that they were written during a time when God’s inerrant word says that no prophets would prophecy. Notice the dates of the following books:

Tobit (225-175 BC)

The Book of Tobit is a work of fiction that has been very popular among Jews and early Christians. This book was considered an ecclesiastical book (i.e., church reading canon but not Scriptural canon) by fathers such as Rufinus of Aquilelia. The book tells the story of Tobit, a righteous Israelite who had been deported to Assyria in 721 BC. Raised by his maternal grandmother to be faithful to Yehovah, he experiences adventures and romance. It’s worth a read as fiction, but based on the date, Hosea and Amos rule Tobit as being outside the canon.

Ecclesiasticus (200-175 BC)

The same is true of Ecclesiasticus. This book is sometimes called Sirach, or “The Book of the All-Virtuous Wisdom of Yeshua ben Sira.” Ben Sira was a Jewish scribe. Scholars say that he wrote down this book of proverbs and sayings somewhere between 200-175 BC, and that his book was translated into Greek by his grandson in 132 B.C. He made no claim to prophetic abilities, and indeed apologized for the poorness of his writing: “Wherefore let me intreat you to read it with favour and attention, and to pardon us, wherein we may seem to come short of some words, which we have laboured to interpret.”141

1 Maccabees (175-135 BC)

This is a very useful history book (especially for the period from 175-135 BC), but it makes no claim to be Scripture and indeed claims to be written after the age of the prophets (see 9:27; 4:46; 14:41). It gives wonderful background information to festivals and the formation of the community into which Christ was born.

Judith (150 BC)

The Book of Judith is a historical novel that shows God’s people winning against their enemies through the intervention of a woman, Judith. This Jewish widow outwits and slays a great Assyrian general, thus bringing deliverance to her oppressed people. It was written by a Pharisee in Palestine sometime in the late second century BC.

Additions to Esther (114 C)

This work, likely written about 114 BC, consists of a number of additions to the Biblical book of Esther. There is an unusual colophon attached to the book at 11:1, which has made many scholars date the “Additions to Esther” to 114 BC. The note says that the Additions were brought from Jerusalem during the fourth year of Ptolemy and Cleopatra. Depending upon which Ptolemy and Cleopatra, this would be dated as 114 BC, 77 BC, or 48 BC.

1 Baruch (200-100 BC)

Most of this book was written between 200 and 100 BC. It was written under the assumed name of Baruch, who was the private secretary of Jeremiah. As such, it is Pseudepigraphal, like some others are.

The Prayer of Manasseh (150 BC)

Most scholars believe this prayer was written sometime in the first or second century BC, though perhaps 150 BC is a good guess. Though Rome does not accept this as canonical, it is accepted by the Orthodox church. It also appears in the late fourth-century Vulgate, Martin Luther’s Bible, in the Roman Rite Liturgy, the Matthew Bible of 1537 and the Geneva Bible of 1599. Again, the date is a giveaway that it is not canonical.

2 Maccabees (100 BC)

This book is not nearly as useful as the first book of Maccabees, since it combines history with fiction. Though it has useful information related to the Maccabean Revolt against Antiochus IV, it also contains bad Pharisaic traditions. The author wrote this as an abridgment of a five volume work by Jason of Cyrene. We no longer have the longer work, and it is uncertain how much of this was directly copied from it. In any case, it makes no claim to inspiration and was written in Greek somewhere around 100 BC (though some extend this to 170-110 BC). The author’s statements about his own writing indicate that he did not think of himself as a prophet. For example, he says, “If it is well told and to the point, that is what I myself desired; if it is poorly done and mediocre, that was the best I could do” (15:38). Indeed, he claims simply to be abridging five volumes written by a Jason of Cyrene (cf. 2:23ff.) and admits that this has been painful labor (2:26ff.).

Bel and the Dragon (100 BC)

This story comprises chapter 14 of the extended book of Daniel. It mocks idolatry and especially opposes the dragon god. Hosea and Amos would rule this out as not belonging in the canon. No prophets were authorized to add it to Daniel since no prophets existed in 100 BC.

The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews (100 BC)

This appears after Daniel 3:23 in Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Bibles. This does not appear in any Hebrew or Aramaic Bibles.

1 Esdras (100 BC)

This Greek verson of the canonical Book of Ezra was written sometime around 100 B.C. Some of the subject matter added is from the book of Nehemiah. It is considered apocryphal in the West and canonical in the East.

2 Esdras (100 BC?)

Though this book is considered apocryphal by Roman Catholics and most Orthodox, it is accepted by the Slavonic (Russian) Orthodox church. They re-label 1 and 2 Esdras as 2 and 3 Esdras. This book is a Jewish apocalyptic writing. There is debate on the dating, with some placing it after AD 70 (as a book of consolation after the Jewish exile) while others date it somewhere between 150-11 BC. If it is dated after AD 70, then the principles of the next chapter apply.

The History of Susanna (1rst century BC)

The History of Susanna is sometimes called Susanna and the Elders. This is included in Daniel 12 in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. However it is not in the Hebrew Bible and is not mentioned in any Jewish literature. This is another 1st century BC addition to the book of Daniel.

Wisdom of Solomon (65 BC)

The Wisdom of Solomon or the Book of Wisdom was written in Alexandria by a first century Jew. His goal was pastoral - to bolster the faith of the Jewish community in a hostile environment. Though a handful of church fathers thought that this book was canonical,142 I will simply point to the date that it was written - 65 BC.

Concluding statement

God has not left us in the dark concerning His Old Testament canon. In addition to Christ’s endorsement of the Hebrew canon (which is identical to the Protestant canon) God has given us sufficient information to clearly rule out anything written between 400-5/4 BC. Every one of the apocryphal books listed above was written during the period that God guaranteed no prophecy would happen. So even if there was a claim to prophecy in the apocrypha (which there is not), the Bible’s self-referential statements would have excluded the apocrypha. So when Rome canonized the books at the Council of Trent, they were not only changing the majority of church opinion (see chapter 1), but they were ignoring the apocryphal books’ self-referential statements, and failing to heed the prophecies of Hosea and Amos. The Protestant canon of the Old Testament has been vindicated using presuppositional arguments.

Objection - What about the claimed quote of 1 Enoch 1:9 in Jude 1:14-15?

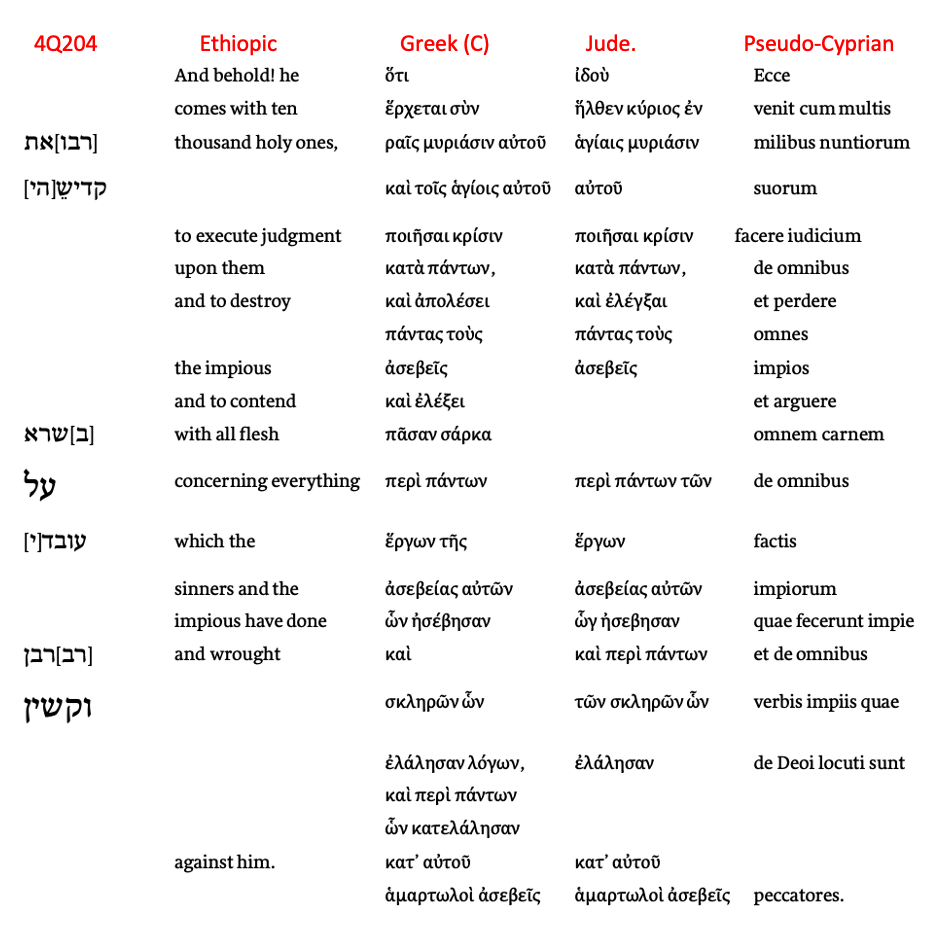

I do not dispute that both Jude and the Pseudepigraphal143 book of 1 Enoch record the same prophecy of Enoch. But I do not believe that Jude quoted any extant copies of this book. The differences in language are too great. Many scholars insist that Jude does indeed quote 1 Enoch rather than quoting a common source or rather than simply receiving his information directly from God. There is debate among these scholars on which version of 1 Enoch Jude quotes since none of the versions perfectly lines up. Since the Ethiopic,144 Syriac,145 and Latin146 versions of 1 Enoch were not yet crafted, and since the only Hebrew fragments of Enoch that have been discovered do not include this verse (4Q202 only includes Enoch 8:4-9:4 and 106), this means that the only versions of Enoch 1:9 in existence that precede Jude are the Aramaic fragment and the Greek. Discussion of any other non-existent versions involves us in conjecture. So let’s compare these two versions:

The Aramaic version that has 1 Enoch 1:9 (4Q204) is very fragmentary. The only words that appear in the fragment are the ones left out of brackets in the following reconstruction:

16 [when he comes with] the myriads of his holy ones [to carry out the sentence against everyone; and he will destroy all the wicked] 17 [and he will accuse all] flesh for all their [wicked deeds which they have committed by word and deed] 18 [and for all their] arrogant and wicked [words which wicked sinners have directed against him].147

There is a lot of conjecture as to what appears between the missing pieces. Thus, the only phrases that we can be certain of are:

the myriads of his holy ones … flesh for all their …arrogant and wicked

Yet even with this fragment, four of those thirteen words are different. 1 Enoch adds “flesh… arrogant and wicked.” With a 30% deviation, it is statistically difficult to see this version as being the basis for Jude’s quote.

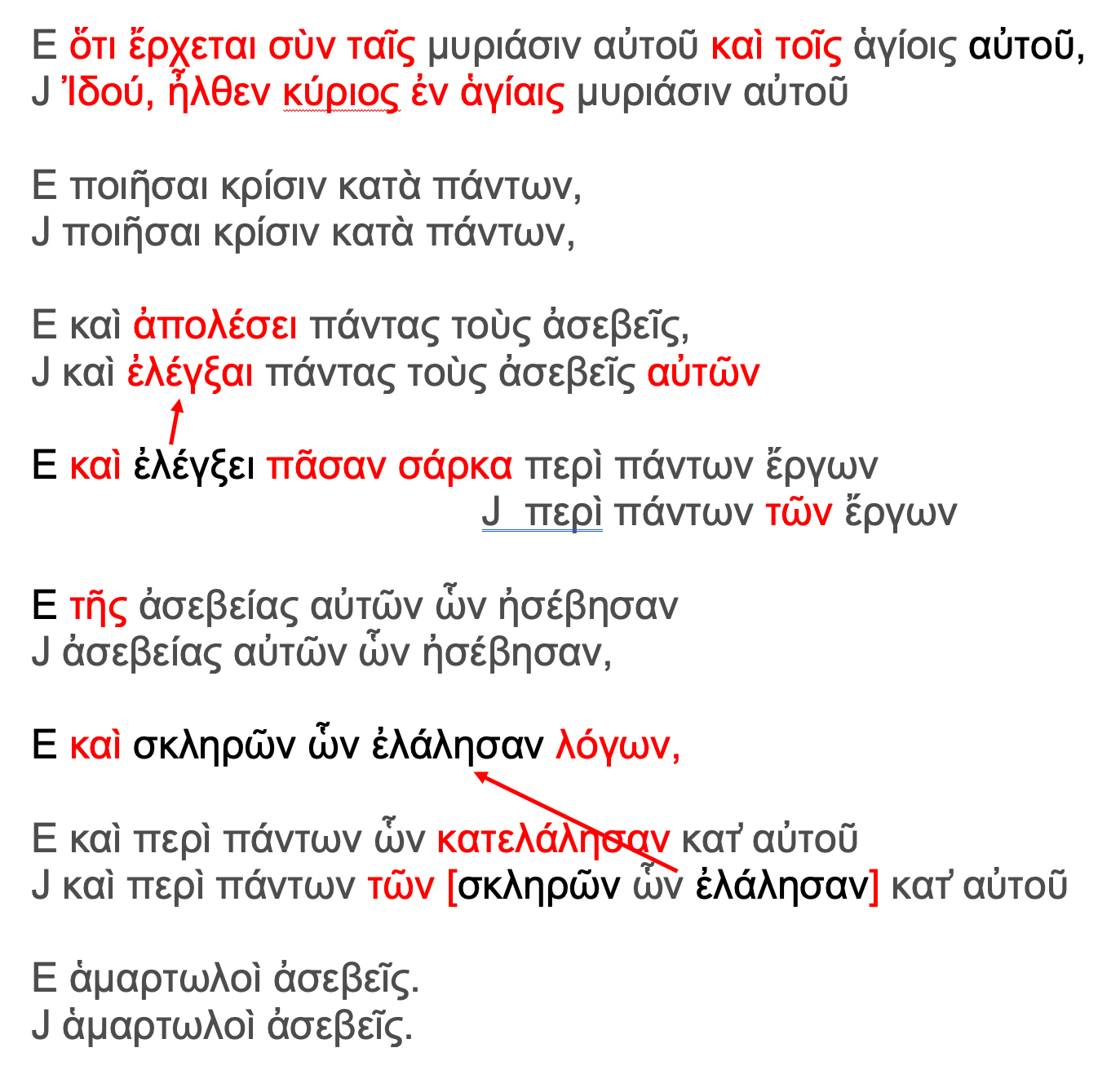

The Greek version of Enoch is also far off from the Greek version of Jude. It is graphed below.

You will notice that the Greek of 1 Enoch 1:9 has 31 words whereas the Greek of Jude’s quote has 36. Of Jude’s 36 Greek words, only 26 are identical. Enoch adds or changes 16 words that are not in Jude and Jude adds or changes 9 words that are not in Enoch.

If the author of Jude had 1 Enoch in front of him, it is clear that he was deliberately changing the wording. Jude says, “Behold the Lord comes with myriads of his holy ones.” In that clause only three words are the same in the Greek. Enoch says “Because,” while Jude says “Behold.” Enoch says “comes,” while Jude uses the past tense “came” (ἦλθεν). Some have speculated that the ἦλθεν reflects a Hebrew perfect, but aside from being bad Greek, that is merely a conjecture (that the Hebrew had a perfect) of another conjecture (that the Hebrew was the original source). Scholars debate both conjectures.

Other changes include the following: Enoch says “he” while Jude says “the Lord.” Enoch has holy ones in the masculine, while Jude has them in the feminine - referring to a specific kind of angel. Jude’s phrase “with his myriads of holy ones” is shorter than the more complex version in Enoch. Jude’s phrase, “to convict all the ungodly” is shorter and stresses God’s judgment and convictions whereas Enoch adds the words “and destroy.” Jude is more specific about the kinds of speech being judged (reviling speech) whereas Enoch speaks of generic evil deeds and words. Enoch adds the words “and,” “all flesh,” “the,” and “destroy,” and it inverts two phrases.

But there are differences with even the later Latin and Ethiopic versions. Consider the following chart:

It is better to say that this ancient history was passed down in Jewish lore just like the creation story and the flood story have been passed down in corrupted forms in most cultures of the world. Those stories are corrupted to varying degrees because there was no inspiration to preserve each jot and tittle of the story in those cultures. But it shouldn’t be surprising that so many cultures have a creation story, flood story, tower of Babel story, etc. On this story of Enoch’s prophecy, only Jude preserves the story 100% accurately. The bottom line is that Jude clearly did not quote the book of Enoch.