Chapter 3: The Infinite Loop

We have a problem.

Run the script from Chapter 2 twice. Say “My name is Alice.” Claude says hello. Run it again and ask “What is my name?” Claude says “I don’t know.”

This is because LLMs are stateless. They have total amnesia. Every request is the first time you have ever met.

To build an agent, we need to fix this by creating artificial memory.

The Illusion of Memory

“Memory” in an LLM isn’t a hard drive. It’s a log file.

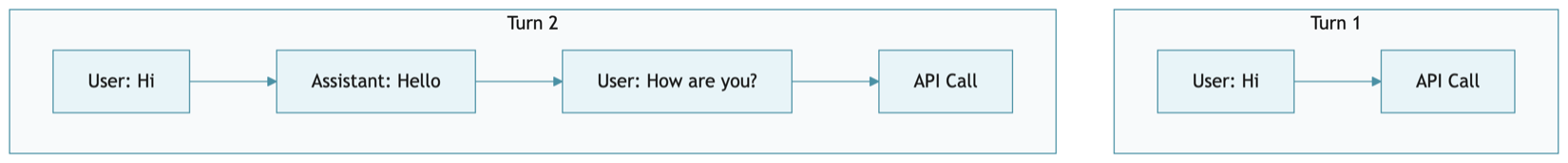

When you chat with ChatGPT, it doesn’t “remember” what you said 5 minutes ago. Behind the scenes, the code sends the entire conversation history back to the model with every new message.

The model sees the full transcript every time. That’s the trick.

We are going to implement this context loop manually. But first, we need to make our code testable.

The Testing Problem

Here’s a hard truth: you cannot test an LLM-powered application by actually calling the LLM.

API calls are slow (2-10 seconds each), expensive (real money per call), and non-deterministic (you might get a different response every time). Imagine running a test suite that costs $5 and takes 20 minutes. You’d never run it.

The solution is dependency injection. Instead of hardcoding the API call inside our agent, we pass in a “brain” object. In production, the brain is Claude. In tests, the brain is a fake that returns predictable responses.

We’ll establish this pattern now, before writing any more production code.

Response Types

Before we build the brain, we need to define what it returns. Claude’s API sends back complex JSON with multiple content blocks. We need simple Python objects to work with.

The Context: Claude can return text, tool calls, or both in a single response. We need data classes to represent these possibilities.

The Code:

17 class ToolCall:

18 """A tool invocation request from the brain."""

19

20 def __init__(self, id, name, args):

21 self.id = id

22 self.name = name

23 self.args = args # dict

ToolCall represents the brain asking us to execute a tool. The id is a unique identifier for tracking (Claude needs it when we report results back). The name is which tool to run. The args is a dictionary of parameters.

We won’t use ToolCall yet—the brain can’t call tools—but we define it now because it’s part of the Thought response type. When we add tools, Claude will return these when it wants to read a file or execute a command.

26 class Thought:

27 """Standardized response from any Brain."""

28

29 def __init__(self, text=None, tool_calls=None):

30 self.text = text # str or None

31 self.tool_calls = tool_calls or [] # list of ToolCall

A Thought is what the brain returns after thinking. It might have text, tool calls, both, or neither. This abstraction will let us swap Claude for DeepSeek later without changing any other code.

The FakeBrain Pattern

Now we can build a fake brain for testing.

The Context: We need a brain that returns predictable responses, tracks how many times it was called, and records what conversation it received.

The Code:

class FakeBrain:

"""Fake brain for testing - returns predictable responses."""

def __init__(self, responses=None):

self.responses = responses or [Thought(text="Fake response")]

self.call_count = 0

self.last_conversation = None

def think(self, conversation):

self.last_conversation = list(conversation) # Store a copy

if self.call_count < len(self.responses):

response = self.responses[self.call_count]

self.call_count += 1

return response

return Thought(text="No more responses")

This goes in test_nanocode.py, not the production code. Notice that FakeBrain has the same interface as our real brain will—a think() method that takes a conversation and returns a Thought.

|

Aside: This pattern—replacing a real dependency with a predictable fake for testing—is called dependency injection. Martin Fowler’s article “Mocks Aren’t Stubs”1 explains the variations (fakes, stubs, mocks, spies). For LLM testing, a simple fake with canned responses is usually all you need. |

Defining Success

Before writing the production code, let’s define what success looks like. These tests will guide our implementation.

Test 1: The brain returns a response

1 def test_handle_input_returns_brain_response():

2 """Verify handle_input returns the brain's response text."""

3 brain = FakeBrain(responses=[Thought(text="Hello from brain!")])

4 agent = Agent(brain=brain)

5 result = agent.handle_input("hi")

6 assert result == "Hello from brain!"

Notice we pass brain=brain to the Agent. This is dependency injection in action.

Test 2: Conversation accumulates

1 def test_conversation_accumulates():

2 """Verify conversation list grows with each interaction."""

3 brain = FakeBrain(responses=[

4 Thought(text="Response 1"),

5 Thought(text="Response 2")

6 ])

7 agent = Agent(brain=brain)

8

9 agent.handle_input("First message")

10 assert len(agent.conversation) == 2 # user + assistant

11

12 agent.handle_input("Second message")

13 assert len(agent.conversation) == 4 # 2 users + 2 assistants

After each exchange, the conversation should have both the user message and the assistant response.

Test 3: Correct message structure

1 def test_conversation_contains_correct_roles():

2 """Verify conversation has correct role alternation."""

3 brain = FakeBrain(responses=[Thought(text="AI response")])

4 agent = Agent(brain=brain)

5

6 agent.handle_input("User message")

7

8 assert agent.conversation[0]["role"] == "user"

9 assert agent.conversation[0]["content"] == "User message"

10 assert agent.conversation[1]["role"] == "assistant"

11 assert agent.conversation[1]["content"] == "AI response"

The messages must have the exact format Claude expects: {"role": "user", "content": "..."}.

Test 4: Brain receives the conversation

1 def test_brain_receives_conversation():

2 """Verify brain.think is called with the conversation list."""

3 brain = FakeBrain()

4 agent = Agent(brain=brain)

5

6 agent.handle_input("Test message")

7

8 assert brain.last_conversation is not None

9 assert len(brain.last_conversation) == 1

10 assert brain.last_conversation[0]["content"] == "Test message"

The brain must receive the full conversation, not just the current message.

Run these tests now—they should all fail:

1 pytest test_nanocode.py -v

1 FAILED test_nanocode.py::test_handle_input_returns_brain_response

2 FAILED test_nanocode.py::test_conversation_accumulates

3 ...

Good. Now let’s make them pass.

The Claude Class

Now the real brain.

The Context: We need a class that wraps the Claude API. It should handle authentication, send conversation history, and parse the response into a Thought.

The Code:

36 class Claude:

37 """Claude API - the brain of our agent."""

38

39 def __init__(self):

40 self.api_key = os.getenv("ANTHROPIC_API_KEY")

41 if not self.api_key:

42 raise ValueError("ANTHROPIC_API_KEY not found in .env")

43 self.model = "claude-sonnet-4-6"

44 self.url = "https://api.anthropic.com/v1/messages"

45

46 def think(self, conversation):

47 headers = {

48 "x-api-key": self.api_key,

49 "anthropic-version": "2023-06-01",

50 "content-type": "application/json"

51 }

52 payload = {

53 "model": self.model,

54 "max_tokens": 4096,

55 "messages": conversation

56 }

57

58 print("(Claude is thinking...)")

59 response = requests.post(self.url, headers=headers, json=payload, timeout=120)

60 response.raise_for_status()

61 return self._parse_response(response.json()["content"])

The Walkthrough:

- Lines 39-41: Load the API key and fail fast if it’s missing.

- Lines 43-44: Store config. We’ll make the model configurable later.

- Line 46: The

think()method is the brain’s interface—same asFakeBrain. - Lines 52-55: The payload includes

"messages": conversation—the full history, not just the current message. This is the context loop. - Line 61: Parse Claude’s complex response format into our simple

Thought.

Now the response parser:

63 def _parse_response(self, content):

64 """Convert Claude's response format to Thought."""

65 text_parts = []

66 tool_calls = []

67

68 for block in content:

69 if block["type"] == "text":

70 text_parts.append(block["text"])

71 elif block["type"] == "tool_use":

72 tool_calls.append(ToolCall(

73 id=block["id"],

74 name=block["name"],

75 args=block["input"]

76 ))

77

78 return Thought(

79 text="\n".join(text_parts) if text_parts else None,

80 tool_calls=tool_calls

81 )

Claude’s API returns a list of “content blocks.” Each block has a type—either "text" or "tool_use". We collect all text blocks into a single string and convert tool_use blocks into ToolCall objects.

The Agent Class (Updated)

Now we update the Agent from Chapter 1 to accept a brain and maintain conversation history.

The Code:

86 class Agent:

87 """A coding agent with conversation memory."""

88

89 def __init__(self, brain):

90 self.brain = brain

91 self.conversation = []

92

93 def handle_input(self, user_input):

94 """Handle user input. Returns output string, raises AgentStop to quit."""

95 if user_input.strip() == "/q":

96 raise AgentStop()

97

98 if not user_input.strip():

99 return ""

100

101 self.conversation.append({"role": "user", "content": user_input})

102

103 try:

104 thought = self.brain.think(self.conversation)

105 text = thought.text or ""

106 self.conversation.append({"role": "assistant", "content": text})

107 return text

108 except Exception as e:

109 self.conversation.pop() # Remove failed user message

110 return f"Error: {e}"

The Walkthrough:

- Lines 89-91: Accept a brain via dependency injection. Initialize an empty conversation list.

- Line 101: Append the user’s message to history before calling the brain.

- Lines 103-107: Call the brain, extract the text, append the response to history.

- Lines 108-110: If the API call fails, remove the user message we just added. This keeps the conversation in a valid state.

Pay attention to line 101: we add the user message before calling the brain. The brain needs to see the full conversation including the current message.

The Main Loop (Updated)

The main loop is now just a thin I/O wrapper:

115 def main():

116 brain = Claude()

117 agent = Agent(brain)

118 print("⚡ Nanocode v0.2 (Conversation Memory)")

119 print("Type '/q' to quit.\n")

120

121 while True:

122 try:

123 user_input = input("❯ ")

124 output = agent.handle_input(user_input)

125 if output:

126 print(f"\n{output}\n")

127

128 except (AgentStop, KeyboardInterrupt):

129 print("\nExiting...")

130 break

131

132

133 if __name__ == "__main__":

134 main()

All the logic is in the Agent class. The loop just reads input, calls handle_input(), and prints the result. This separation makes the agent testable—we test Agent.handle_input() directly without needing to mock input() or print().

Verify the Tests Pass

Run the tests again:

1 pytest test_nanocode.py -v

1 test_nanocode.py::test_handle_input_returns_brain_response PASSED

2 test_nanocode.py::test_conversation_accumulates PASSED

3 test_nanocode.py::test_conversation_contains_correct_roles PASSED

4 test_nanocode.py::test_brain_receives_conversation PASSED

All green. The tests verify our implementation without making a single API call.

Test the Memory

Now test with the real brain:

1 python nanocode.py

Try this conversation:

1 ❯ I am building a Python agent.

2 (Claude is thinking...)

3

4 That sounds exciting! Building a Python agent is a great project...

5

6 ❯ What language am I using?

7 (Claude is thinking...)

8

9 You are using Python.

The conversation list is doing its job.

The Context Window Problem

You might be thinking: “Can I keep this running forever?”

No.

Every loop iteration, the messages list grows:

| Turn | Approximate Tokens |

|---|---|

| 1 | 50 |

| 10 | 5,000 |

| 100 | 50,000 |

Eventually, you hit the context limit—200k tokens for Claude Sonnet, 128k for DeepSeek, as low as 4k for some local models. Exceed it, and the API returns 400 Bad Request. Our error handling on line 108 catches this and reports the error, so the agent won’t crash silently. But the conversation is effectively stuck—every subsequent message will fail too, since the history is still too long.

For now, restarting the agent clears the history and gets you back on track. We’ll add proper context compaction—tracking token usage from the API response and automatically summarizing old messages before they overflow—when we build the feedback loop in Chapter 9. That’s where conversations actually blow up, and where the fix will earn its keep.

Wrapping Up

Claude remembers now—or rather, we’ve tricked it into thinking it does. The conversation list grows with every turn, and FakeBrain lets us test the whole thing without spending a cent.

Both patterns will carry through the rest of the book. Every brain we build (Claude, DeepSeek, Ollama) will implement the same think() interface, and FakeBrain will test them all.

One loose end: our code is hardwired to Anthropic’s API. If we want to add DeepSeek or a local model, we’d have to duplicate a lot of code.

https://martinfowler.com/articles/mocksArentStubs.html↩︎