Concerns and Risks Surrounding AI

|

The concerns around AI are serious. The risks are real. Sometimes they are expressed in hysterical ways, but, when you drill down, the impact of AI has the potential to be enormously destructive. |

The many issues and concerns surrounding AI can fill volumes on their own. Here’s a word cloud of the topics I monitor. I’m sure I’m missing a few.

There’s lots of information available on each of these topics, and I encourage you to read as deeply as you can. It’s possible you’ll conclude that the risks outweigh the benefits, and that you don’t want to pursue the use of AI, whether personally or within your organization. In the end it’s a personal choice.

If you google “books regarding the risks of AI” you’ll find a selection of worthwhile volumes. A recent podcast that I found particularly chilling was Ezra Klein’s chat with Dario Amodei, Anthropic’s co-founder and CEO (the company that develops Claude.ai). You learn that these companies are aware of the risks. Amodei refers to an internal risk classification system called A.S.L., for “AI Safety Levels” (not American Sign Language). We’re currently at ASL 2, “systems that show early signs of dangerous capabilities—for example ability to give instructions on how to build bioweapons.” He describes ASL 4 as “enabling state-level actors to greatly increase their capability… where we would worry that North Korea or China or Russia could greatly enhance their offensive capabilities in various military areas with AI in a way that would give them a substantial advantage at the geopolitical level.” Chilling stuff.

Within this grim context, I’ll highlight the most pertinent issues for writers and publishers.

Copyright infringed?

|

The copyright issues are a miasma of complexity and ambiguity. It appears certain that some books still in copyright were included in the training of some LLMs. But it’s certainly not the case, as many authors fear, that all of their work was hoovered up into the large language models. |

The copyright issues are both specific and broad. It’s well-known that many of the LLMs were trained on the open web—everything that can be scraped from the 1.5 billion sites on the web today, whether it’s newspaper articles, social media posts, Wikipedia, web blogs and, apparently, transcripts of YouTube videos.

It’s provable that at least one of the LLMs ingested the actual text of thousands of books not in the public domain. Possibly others did as well.

Was it legal to ingest all of this text to help build billion-dollar AI companies, without any compensation to the authors? The AI companies make their argument around fair use; the courts will eventually decide. Even if it was legal, was it ethical or moral? The ethics appear less complex than the legal considerations. You decide.

The laws surrounding copyright obviously did not anticipate the unique challenges that AI brings to the issue, and searching for legal solutions will take time, probably years.

Here’s a catalog of fifteen of the most prominent suits, not all of them having to do with books, but also images and music. And here’s another list that updates the status of all of the, by their count, 30 lawsuits, to September 1, 2024.

This same website, ChatGPT is eating the world is an excellent source for following and (at least partially) understanding the latest developments in the ongoing litigation.

Copyright and AI for authors

|

Authors face additional issues surrounding the copyright-ability of AI-generated content. |

The U.S. Copyright Office’s position on the copyright-ability of AI-generated content states that AI alone cannot hold copyright because it lacks the legal status of an author. That makes sense. But this assumes 100% of the work is AI-generated. As discussed elsewhere, few authors are going to let AI generate an entire book. More likely it will be 5%, or 10% or… And here the Copyright Office stumbles (as would I).

In a more recent ruling the Office concluded that a graphic novel comprised of human-authored text combined with images generated by the AI service Midjourney constituted a copyrightable work, but that the individual images themselves could not be protected by copyright.“ Jeez!

At the end of July the Office published “Part 1 of its report on the legal and policy issues related to copyright and artificial intelligence, addressing the topic of digital replicas.”

The New York Times offers a glimpse into how the Copyright Office “is reviewing how centuries-old laws should apply to artificial intelligence technology, with both content creators and tech giants arguing their cases.”

|

Suffice it to say that authors and publishers need to be alert to evolving copyright challenges, on multiple fronts. |

What are the long-term implications?

Some compare the current litigation to the Google books lawsuit, which took 10 years to legally resolve. Who knows how long the appeals process will drag out for these filings.

But that may not be a publisher’s most serious issue. It’s perception. AI is radioactive within the writing and publishing community. For many authors the well has been poisoned. Anything that even smacks of AI draws intense criticism.

There are numerous examples. In a recent incident Angry Robot, a UK publisher “dedicated to the best in modern adult science fiction, fantasy and WTF,” announced that it would be using AI software, called Storywise, to sort through an anticipated large batch of manuscript submissions. It took just five hours for the company to drop the plan and return to the “old inbox.“

The startup Prosecraft, “the world’s first (and only!) linguistic database of literary prose” was shut down in the blink of an eye.

The unbearable dilemma for trade publishers in using AI tools internally: if your authors find out, you’ll have a hard time weathering the resulting storm. I believe that publishers have no choice but to be brave, to adopt (at least some of) the tools, explain clearly how those tools are trained and how they’re utilized, and push on.

In the UK, The Society of Authors takes a hardline approach: “Ask your publisher to confirm that it will not make substantial use of AI for any purpose in connection with your work—such as proof-reading, editing (including authenticity reads and fact-checking), indexing, legal vetting, design and layout, or anything else without your consent. You may wish to forbid audiobook narration, translation, and cover design rendered by AI.”

The Authors Guild appears to accept that “publishers are starting to explore using AI as a tool in the usual course of their operations, including editorial and marketing uses.” I don’t think that many members of the Guild are as understanding.

Licensing content to AI companies

Many publishers, and not-as-many authors, are searching for ways to license content to AI companies. Everyone has a different idea of what the licensing terms should be, and how much their content is worth, but at least the discussions are underway. There’s a general sense across the industry that agreeing to licensing deals now lessens the argument that the AI vendors had no choice but to seize copyrighted works. At the same time there’s a sense of “well, they stole all of our books anyway. We might as well earn something from the theft.”

Various LLM vendors have taken licenses for specific content, some books, but mostly news, social media, and other online text and data. Are the AI companies only going to license the crème de la crème of content? Do they need the skim milk as well? Are their relatively few licenses just window-dressing to mitigate damages if they lose the big lawsuits?

There are also concerns about discoverability. If your published work cannot be—in some manner—referenced via AI searches and conversations, does it become less visible? I’ll talk more about AI and search below.

In early 2025 the publishing industry was startled to learn that HarperCollins had struck a deal with one of the large LLM companies for a 3-year license for an unspecified number of nonfiction backlist titles. The deal itself wasn’t startling, but the terms were—$5,000/title, to be split 50/50 with the book author(s). No one I’ve spoken with expected books to command more than perhaps $100 per title, and as of May 2025, no other deals of a similar size have emerged.

There are several startups looking to work with publishers (and, in one case, individual authors). ProRata.ai and Created by Humans are both interesting in this regard.

In mid-July 2024, Copyright Clearance Center (CCC), long the publishing industry’s top player for collective copyright licensing, announced the availability of “artificial intelligence (AI) re-use rights within its Annual Copyright Licenses (ACL), an enterprise-wide content licensing solution offering rights from millions of works to businesses that subscribe.” This is not a blanket license.

Publishers Weekly covered the announcement, quoting Tracey Armstrong, president and CEO of CCC, as saying “It is possible to be pro-AI and pro-copyright, and to couple AI with respect for creators.”

It’s not all-encompassing, covering only “internal, not public, use of the copyrighted materials.” Nonetheless, this could be a milestone in moving publishing closer to a degree of cooperation with the large language model developers.

It’s too late to avoid AI

|

For authors and publishers who prefer not to be sullied with AI, the news is bad: you’re using AI today, and have been using it for years. |

In the next few sections I want to dance around the ambiguities surrounding AI use. I’ll try to walk you through the issues, many of them interrelated.

Artificial intelligence, in different forms, has already been integrated into most of the software tools and services we use every day. People rely on AI-powered spell- and grammar-checking in programs like Microsoft Word and Google Docs. Microsoft Word and PowerPoint apply AI to provide writing suggestions, to offer design and layout recommendations, and more. Virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa use natural language processing to understand voice commands and respond to questions. Email services leverage AI to filter messages, detect spam, and send alerts. AI powers customer service chatbots and generates product recommendations based on your purchase history and queries.

And much of this is based on Large Language Models, as it is with Chat AI.

For an author or editor to say, “I don’t want AI used on my manuscript,” is, broadly speaking, all but impossible, unless both they and their editors work with typewriters and pencils.

They could try saying, “I don’t want generative AI” used on their book. But that’s a tough one to slice and dice. Grammar-checking software was not originally built on generative AI. Grammarly has added AI as an ingredient to its product, as will all other spelling and grammar checkers. Generative AI is also core to the marketing software on offer.

When authors use AI

Another aspect of authors and the use of AI has similarities to the copyright issue discussed above. In the extreme, we’re seeing 100% AI-generated content being published on Amazon. Most of it (all of it?) is of terrible quality, but that doesn’t prevent it from being published. (See also the Amazon section.) More concerning for publishers is AI-generated submissions. Yes, AI ups the quantity, but large publishers already have a filter for quantity. The filters are called agents. They are the ones who are going to have to figure out how to handle the quantity problem, and apparently they’re going to have to find a solution that doesn’t employ AI.

It’s something of an existential problem—do I want to publish a book written by ‘a machine’? For most publishers that’s an unequivocal ‘no.’ Easy peasy. Well, what about a book where 50% of the content was generated by an LLM, under a capable author’s supervision? Hmm, let’s try a ‘no’ on that as well. OK: then what about 25%, or 10%, or 5%? Where do you draw the line?

And, now that you’ve entered the line-drawing business, how do you resolve the dilemma that spelling and grammar tools now rely, at least in part, on generative AI? What about AI-driven transcription tools, like Otter.ai, or the transcription feature built into Microsoft Word?

I can’t find any trade publisher that has declared they will not publish a work with a pre-specified quantity of AI-generated text. Here’s the Authors Guild on the topic:

“If an appreciable amount of AI-generated text, characters, or plot are incorporated in your manuscript, you must disclose it to your publisher and should also disclose it to the reader. We don’t think it is necessary for authors to disclose generative AI use when it is employed merely as a tool for brainstorming, idea generation, or for copyediting.”

Needless to say, ‘appreciable’ is not defined (Oxford defines it as “large enough to be noticed or thought important”), but the post goes on to explain that the inclusion of more than “de minimis AI-generated text” would violate most publishing contracts. De minimis, in legal terms, is not precisely specified, but, generally speaking, means more or less the same as appreciable.

Can AI be reliably detected in writing?

I hosted a webinar on AI detection, sponsored by BISG, in May 2024. The replay is online on YouTube. Jane Friedman offered a comprehensive write-up of the webinar in her Hot Sheet newsletter.

For many authors, the toxicity of AI means keeping it far away from their words. Publishers bear a special burden—they don’t create the text, but, once published, they shoulder a substantial obligation to the text. We’ve seen lots of dynamite blow near incendiary books, whether it be around the social implications of the content, or the plagiaristic purloining of other writer’s words and ideas. Now with AI we face a whole new set of ethical and legal issues, none of which were outlined in publishing school.

Part of it seems similar to what people worry about for students, that using AI is somehow cheating, similar to cribbing from a Wikipedia article, or perhaps just asking a friend to write your essay.

One of our webinar speakers, an educator, José Bowen (whose book I reference below), shared his disclosure for students. It’s not exactly what you use for an author, but it demonstrates some sort of “risk levels” of AI use.

Template Disclosure Agreement for Students

I did all of this work on my own without assistance from friends, tools, technology, or AI.

-

I did the first draft, but then asked friends/family, AI paraphrase/grammar/plagiarism software to read it and make suggestions. I made the following changes after this help:

Fixed spelling and grammar

Changed the structure or order

Rewrite entire sentences/paragraphs

I got stuck on problems and used a thesaurus, dictionary, called a friend, went to the help center, used Chegg or other solution provider.

I used AI/friends/tutor to help me generate ideas.

I used assistance/tools/AI to do an outline/first draft, which I then edited. (Describe the nature of your contribution.)

And so a publisher could draft something like this for their authors. Let’s say the author discloses the top level: I used AI extensively, then edited the results. What then? Do you automatically reject the manuscript? If so, why?

And, meanwhile, if you’re paying attention, you learn that that manuscript you just read and loved, which the author swore wasn’t even spell-checked by Grammarly, could have in fact been 90% generated by AI, by an author expert at concealing its use.

You’re then forced to rethink the question. It becomes, “Why am I so damned determined to detect this thing which is undetectable?”

In part it’s the alarmist concern surrounding the copyrightability of AI-generated text. The copyright office won’t offer copyright protection to 100% AI-generated text (or music, or images, etc.). But what about 50% AI-generated text? Well, we would only cover the 50% generated by the author. And how would you know which half? We’ll get back to you on that one.

Wouldn’t it be great if you could just feed each manuscript into some software that would tell you if AI had been used in creating the text?

Leaving aside the issue that the only way to do this would be by employing AI tools, the more important question is, would the software be (sufficiently) accurate? Could I rely on it to tell me if AI had been used in creating a manuscript? And could I depend on it not to produce “false positives”—to indicate that AI had been used, when in fact it had not?

There’s now lots of software on the market that tackles these challenges. Many of the academic studies evaluating this software point to its unreliability. AI-generated text slips through. Worse, text that was not generated by an AI is falsely-labeled as having been contaminated.

But book publishers are going to want some kind of safeguards in place. It appears that, at best, these tools could alert you to possible concerns, but you would always need to double check. So perhaps it might alert you to texts that need to be more carefully examined than others? Is this an efficiency?

True efficiency will be found in moving beyond concerns about the genesis of a text, instead maintaining our existing criteria as to the quality of the submitted work.

Job loss

“AI will not replace you. A person using AI will.” —Santiago Valdarrama (January, 2023)

Job loss from AI adoption could be severe. Estimates vary widely, but the numbers are grim. There are obvious examples: San Francisco’s driverless taxis eliminate… taxi and rideshare drivers. AI-supported diagnostics reduce the need for medical technicians.

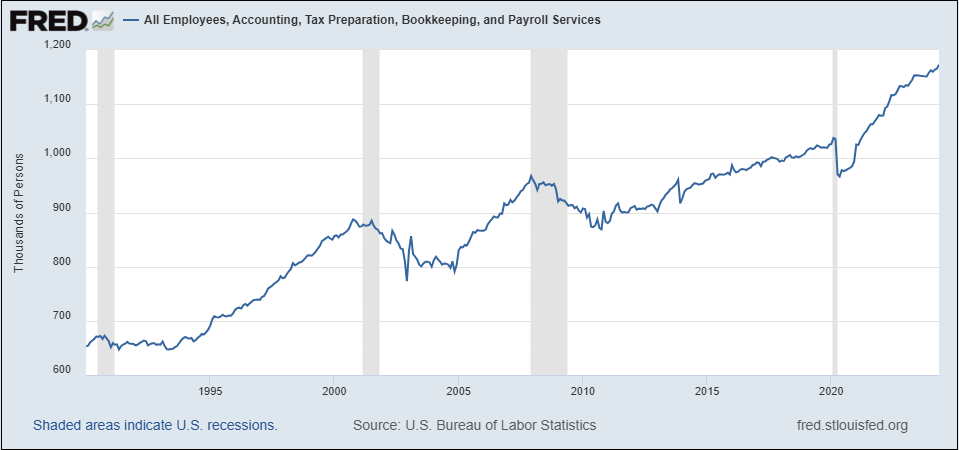

The optimist in me points to, as one example, the introduction of the spreadsheet and its impact on employment. As you see in the chart below, employment in “Accounting, Tax Preparation, Bookkeeping, and Payroll Services” has nearly doubled since 1990—hardly an indictment of spreadsheets and other technologies that have largely automated these tasks.

Ethan Mollick’s study with the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) was an experiment that sought to better understand AI’s impact on work, especially on complex, knowledge-intensive tasks. The study involved 758 BCG consultants, randomly assigned to use or not use OpenAI’s GPT-4 for two tasks: creative product innovation and business problem solving. The study measured the performance, behavior, and attitudes of the participants, as well as the quality and characteristics of the AI output.

Among the findings was that “AI works as a skill leveler. The consultants who scored the worst when we assessed them at the start of the experiment had the biggest jump in their performance, 43%, when they got to use AI. The top consultants still got a boost, but less of one.” The full article is revealing, and as with all of Mollick’s work, provocative yet accessible.

Education

Education has been front-and-center in the pro and con debates about AI. The introduction of AI into classrooms is largely seen as a curse, or at least a challenge. Other educators, like PW’s keynoter Ethan Mollick, embrace AI as a remarkable new tool for educators; Mollick insists that his students work with ChatGPT.

The best book on the topic is Teaching with AI: A Practical Guide to a New Era of Human Learning by José Antonio Bowen and C. Edward Watson.

I’m not going to delve into educational publishing in this book—it’s a vast topic, demanding a separate report. Arguably publishing is becoming of secondary interest within education: AI tools are software, not content, per se. Or, stated another way, has software become content?

The future of search

|

Search is a fraught topic in AI. I encourage you to visit perplexity.ai to get a glimpse into where things are headed. The next couple of times you’re thinking of starting a Google search head over to Perplexity instead. |

Perplexity goes a step beyond search links, rephrasing the information it gathers from multiple sources so that you really don’t have to click a link. It provides links to its sources, but clicking them is unnecessary—you’ve already got the answer to your question.

Google has moved in the same direction with its “AI Overviews.” After Perplexity, return to Google search and type in the same query, and compare Google’s AI summary to Perplexity’s. It won’t be as good.

This seemingly modest shift has huge implications for every company and every product that relies, at least in part, on being discovered through search engines. If searchers are no longer being sent to your site, how can you engage them and convert them to customers? Simple answer, you can’t.

More information is available in this report from Bain, “Goodbye Clicks, Hello AI: Zero-Click Search Redefines Marketing.”

It’s still early days for AI and the transformation of search. Stay tuned.

Junk books on Amazon

|

AI-generated junk books on Amazon are a problem, though their severity may be more visceral than literal. On the one hand these books are spamming the online bookstore with low-quality and plagiarized content, sometimes using the names of real authors to deceive customers and take advantage of their reputations. The books are not only a nuisance for readers but also a threat for authors, potentially depriving them of hard-earned royalties. AI-generated books also affect the ranking and visibility of real books and authors on Amazon’s site, as they compete for the same keywords, categories, and reviews. |

Amazon now requires authors to disclose details of their use of AI in creating their books. No doubt this can be abused.

Try searching on Amazon for “AI-generated books.” There are lots. Some of the results are how-to books about the use of AI for creating books. But others are, unabashedly, AI-generated. “Funny and Cute cat images-You are can’t see this types of photos in the world-PART-1” (stet) is credited to Rajasekar Kasi. There are no details of his (?) bio on an author page, but six other titles are credited to the name. The book, published August 26, 2023, has no reviews and no sales rank. The ungrammatical title of the ebook doesn’t match the ungrammatical title on the cover of the print book.

But other authors are clearly using AI extensively in the creation of their books, and not disclosing. As I discuss above, detecting AI use is next-to-impossible with skilled ‘forgers.’ Coloring books, journals, travel books and cookbooks are being generated with AI tools in a fraction of the time and effort of traditional publishing.

Search “korean vegan cookbook” and you’ll find the top title, “The Korean Vegan Cookbook: Reflections and Recipes from Omma’s Kitchen,” by Joanne Lee Molinaro, in first place. But trailing not far behind it are other titles that are obvious rip-offs. “The Korean Vegan Cookbook: Simple and Delicious Traditional and Modern Recipes for Korean Cuisine Lovers” has two reviews, including one that notes “This is not a vegan cookbook. All the recipes have meat and eggs ingredients.” But the book is #5,869,771 in sales rank, versus the original, which stands at #2,852 on the list.

It’s difficult to determine the extent of the harm caused.

Amazon has policies in place that allow it to remove any book that fails to “provide a positive customer experience.” Kindle content guidelines forbid “descriptive content meant to mislead customers or that doesn’t accurately represent the content of the book.” They can also block “content that’s typically disappointing to customers.” It is the sheer volume that defeats Amazon’s watchers? Or is there another reason?

Bias and Deepfake Images

LLMs are trained on that which has already been published online, and on books obtained from pirates. What has already been published is rife with bias, and so LLMs reflect that bias. And of course not just bias, but hate, reflected in its learnings, and now a potential output in AI-generated words and images. Porn is another natural beneficiary of the AI’s remarkable facility with images, and there are recent troubling stories of young women finding fabricated nude images, their male classmates as likely suspects. The New York Times reported separately about an increase in online images of child sexual abuse.

Authors and publishers need to be aware of these built-in limitations when using AI tools.