JavaScript Fundamentals

Practical application is always more important than theory. Therefore, in this course, don’t expect long theory or an opinionated rant about how JavaScript code should be written. The objective of this course is that you understand how JavaScript works from a practical point of view so that you can get started with writing code.

Your First JavaScript Line

When learning programming, we often start with writing and executing a "Hello World!" program that writes the Hello World! message to the output of our choice. In some languages like Java, it takes a lot to write Hello World to the standard output. In JavaScript, we get away with one single line:

1 console.log( "Hello World!" );

The semicolon marks the end of the statement. Semicolons are optional in JavaScript, because they are inserted automatically by the JavaScript interpreter. However, it is good practice to stick to inserting semicolons, because there are some edge cases, when the JavaScript interpreter inserts semicolons to the wrong place.

You may ask, where can I execute this line? Let me give you a few options.

- Open CodePen. CodePen is an online web development sandbox containing boxes for HTML, CSS, and JavaScript code. You need to write your code in the JavaScript box. You can see the result in the console. Whenever you make a change to the JavaScript code, a new line appears in the console.

- You can also write your code at the bottom of the CodePen console. You can see the same result after pressing enter.

- Alternatively, you can open a new tab in your browser. Most browsers are the same in this aspect. This item uses the terminology of Google Chrome in English. After opening a Chrome tab, right click inside the tab and select Inspect from the context menu. Alternatively, you can press

Ctrl + Shift + Iin Windows or Linux, andCmd + Shift + Iin Mac. Once the Chrome developer tools pops up, you can see a menu bar at the top of the developer tools. This menu bar starts with Elements, Console, Network, and so on. Select Console. You can now see a similar console as the CodePen console. The>sign is the prompt. You can enter your JavaScript code after the>.

You will find exercises in the book from time to time. Try solving them on your own. If you get stuck, revise the book until you are comfortable with the material. Some exercises have solutions below the exercise, while you are on your own in case of others.

Exercise 1. Try out the above three methods to run the Hello World! program. Experiment in the Chrome developer tools console what happens if you use console.info, console.warn, or console.error instead of console.log.

Solution: In the Chrome deverloper tools console, check out the color of the message and the icon in front of the message in case of using console.log, console.info, console.warn, and console.error. These colors and icons represent logging levels that are more or less uniform in every programming language. Logging is a way to record what happened in your system. Logging is important for discovering errors in your system in hindsight, and replay what happened exactly.

If you typed the message console.log( "Hello World!" );, you can see the following evaluation:

1 "Hello World!"

2 undefined

The first value is a console log, which is a value written to the console by the console.log function.

The second value is undefined, symbolizing that the console.log function does not have a defined returned value. You don’t have to understand what this means yet until the section on Functions. Until then, just accept that the undefined value will appear after your console log.

Notice your statement can span multiple lines. Press enter inside the expression to separate content into two lines. Reformat your code in the above code editor as follows:

1 console

2 .log(

3 "Hello world!"

4 );

As you can see, you can format JavaScript code in any way you want. The interpreter will not care about the redundant whitespace characters.

If your code spans multiple lines and you are in a console, pressing Enter normally executes the line. If you want to add a newline character without executing the code, press Shift + Enter.

Experiment a bit more with the log. Instead of “Hello World!”, write 5 + 2. You should see the following:

1 > console.log( 5 + 2 );

2 7

3 undefined

> symbolizes the input of the console.

By the way, you don’t even need console.log to write the outcome of the 5 + 2 sum to the standard output:

1 > 5 + 2

2 7

5 + 2 is an expression. The JavaScript interpreter takes this expression and evaluates it. Once this expression is evaluated, its value appears as the output. Notice this is not a log message. In case of a log message, a message is logged, and then the return value of the console.log is written to the console. The return value of console.log is always undefined. As we evaluated the expression directly, we don’t have this undefined second line on the console.

An alternative online development sandbox is JsFiddle. Try it out by entering the following code in the JavaScript box of the editor:

1 document.body.innerText = 'Hello World!';

After entering this code, the text Hello World! appears in the Output. The task of this sandbox is to assemble an HTML page, and this command told the sandbox what to display in the document body.

Congratulations! You managed to write Hello World! to the console twice. Let’s see what we learned:

- console.log writes a log message to the console

-

"Hello World!"is a string. One way to formulate a string is using double quotes. Mind you,'Hello World!'is also a valid string notation in JavaScript - there is a semicolon at the end of the statement. The semicolon itself is optional, but I recommend using it

While reading this tutorial, I encourage you to keep CodePen open, and play around with the examples.

Later we will learn how to

- execute JavaScript in our browser developer tools,

- embed JavaScript in HTML pages,

- execute JavaScript using node.js.

Comments

When writing code, it is important that others can read it too. This is why it is beneficial to comment our code. JavaScript comments are similar to the C++ and Java commenting format. When the JavaScript interpreter reads comments, it completely ignores their content:

- Everything between

/*and*/is ignored by the interpreter - Everything after

//on the same line is ignored by the interpreter.

Examples:

1 let a = 5 + 2; // This is a single line comment lasting until the end of the line.

2

3 /*

4 A comment that can span multiple lines.

5 Everything inside the comment will be ignored by the JavaScript interpreter.

6 let b = 2;

7 */

The above code is interpreted as:

1 let a = 5 + 2;

Everything else is ignored.

Why do we use comments? To avoid ending up in similar situations:

1 //

2 // Dear maintainer:

3 //

4 // Once you are done trying to 'optimize' this routine,

5 // and have realized what a terrible mistake that was,

6 // please increment the following counter as a warning

7 // to the next guy:

8 //

9 // total_hours_wasted_here = 42

10 //

My other favorite is:

1 // I dedicate all this code, all my work, to my wife, Darlene, who will

2 // have to support me and our three children and the dog once it gets

3 // released into the public.

Source: StackOverflow

Summary: write readable code with good comments!

Exercises

Exercise 2: Without running the code, determine what is written to the standard output:

1 console.log( 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 );

2 2 + 4;

3 console.log( 'End' );

Exercise 3: Run the code of Exercise 2 both in CodePen and in your browser.

Exercise 4: Add comment symbols to the code of Exercise 2 such that the program only prints the End message.

Data types in JavaScript

Most programming languages help you create values that symbolize a number, a character in a text, or a longer text. You can also symbolize the concept of true and false values using booleans. You can also create values that symbolize the absence of a value. These values are all called primitive data types.

The name primitive does not come from a negative place. These data types are neither stupid, nor inferior to any other data types we use in JavaScript. The name primitive comes from their simplicity. The other data types you will learn later are composite, and they consist of many primitive data types.

Why are data types important for us?

For instance, whenever you check your emails, go on Facebook, or check your bank account, you always see data: your name, your messages, the current date and time, and in the settings, you can also see other features of your account.

Data have types. We tend to use an integer (whole number, without a fractional part) than text. A checkbox can have two possible values: true or false. These data types are also unique. For each data type, different operations apply, and their possible values are also different.

In JavaScript, there are six primitive types:

- boolean (

trueorfalse) - number (including integers like

1,-2, and floating point numbers like1.1,2e-3) - string (

''or"",'ES6 in Practice'or"ES6 in Practice") - null type (denoted by

null) - undefined (denoted by

undefined) - Symbol (don’t worry about them yet)

We will soon learn more about anomalies arising from restrictions on floating point precision.

For instance, in the 2 * 3 operation, * is the operator symbolizing multiplication. Multiplication has two operands: 2 and 3.

Some important operators are:

-

+stands for addition. Example:2 + 3is5. -

-stands for subtraction. Example:2 - 3is-1. - If there is no operand on the left of

+or-, then+or-becomes a sign. Examples:+3or-2. -

*stands for multiplication. Example:3 * 2is6. -

/stands for division. Example:3 / 2is1.5. -

%stands for the modulus operation, which is the remainder of a number divided by another number using the rules of integer division. Example:5 % 2is1, because5divided by2is2, and the remainder is1. In other words, the mod 2 remainder of 5 is 1. -

**is the power operator. Example:2 ** 3(two to the power of three) is2 * 2 * 2, which is8.

At the bottom of the console in CodePen, there is a line with a > sign. This is where you can enter JavaScript expressions. Let’s try some. Enter the expression you see after the > sign. Then press enter. You can see the result appear on the next line.

1 > 5

2 5

3

4 > 5 + 2

5 7

6

7 > 7 % 5

8 2

9

10 > 5 ** 2

11 25

Operations can be grouped together using parentheses. Parentheses override the priority of executing operations. For instance, in mathematics, multiplication has higher priority than addition. This means, 1 + 2 * 3 is the same as 1 + (2 * 3).

Let’s see an example for using parentheses:

1 > 5 * ( 1 + 2 * ( 3 + 4 ) )

2 // 5 * ( 1 + 2 * 7 )

3 // 5 * ( 1 + 14 )

4 // 5 * 15

5 75

Opposed to mathematics, we do not use brackets or braces to group operations. Parentheses can be used within parentheses. It is also important to construct valid expressions with parentheses, which means that each closing parenthesis should belong to a preceding opening parenthesis.

Similarly to mathematics, different operators have different priority (also referred to as precedence). When an operation has to be performed before another operation, we say that this operator:

- has higher priority,

- binds stronger.

Most operators have either one or two operands. This means the operator transforms either one or two values to a new value. Examples:

- The operands of

5 + 2are5and2. The+operator transforms these operands to7. - The operand of

-(2)is(2). I put parentheses around the2to emphasize that-is an operator and not a symbol to describe an integer.

Operators bind their operands. We have already seen that some operators bind stronger than others. For instance, multiplication binds stronger than addition:

1 5 * 2 + 3 ----> 10 + 3 ----> 13

We have also seen that the priority of operators can be overridden using parentheses:

1 5 * (2 + 3) ----> 5 * 5 ----> 25

The basic arithmetic operations (+, -, *, /, **) and the two signs (+, -) have the following priority:

- Signs:

+or-can stand in front of a number. This sign is evaluated first. - Power:

**binds the strongest out of the operators with two operands. - Multiplication and division:

*and/ - Finally, addition and subtraction:

+and-

The modulus operation was not placed in the above priority order, because most of the time, you won’t need it in a complex expression. In the unlikely case you used it together with other operators, use parentheses. The % operator binds just as strongly as multiplication and division does. However, when using % in a complex expression, parentheses increase the readability of your code.

Exercise 5: Determine the type of the following expressions.

7 % 2"""false"- true

2.5

Exercise 6: Calculate the value of the following expressions:

5 - -12 - 2 * 22 + 2 * 3 ** 2

Exercise 7: Suppose you invest a hundred thousand dollars. Use JavaScript to determine how much money you will have after 1, 2, 5, and 20 years, provided that the annual interest rate is 2%. Help: an annual interest rate of 2% means that you will get 102% of your current money in one year. The ratio between 102% and the current amount (100%) is 1.02.

Exercise 8: Determine which expressions are valid.

2 ** 2 ** 2 ** 2( 1 ) + (2 * ( 3 ) )( 1 + 2 ) * ( 3 * 4 ) ) * ( ( ( 5 - 2 ) * 3 )- ( 2 + 2)

The number type

Handling numbers is mostly straightforward. You have the four arithmetic operations ( +, -, *, /) available for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division respectively.

The % operator is called modulus. a % b returns the remainder of the division a / b. In our example, 7 / 5 is 1, and the remainder is 2. The value 2 is returned.

The ** operator is called the exponential operator. 5 ** 2 is five raised to the second power.

Exercise 9. Match the following expressions with the possible values below.

Expressions:

5 ** 2 + 111 * 11 - (-4)1e2 - 11 * 8 - 2 * 2 / 4

Values: 26, 711, 11, 165, 125.

Let’s see some more surprising floating point operations.

1 > 0.1 + 0.2

2 0.30000000000000004

3

4 > 3.1e-3

5 0.0031

Some more info on floating points. Due to the way how numbers are represented, 0.1 + 0.2 is not exactly 0.3. This is normal and occurs in most programming languages.

3.1e-3 is the normal form of 0.0031. Read it like the exact value of 3.1 times ten to the power of minus three. Although the form is similar to 3.1 * (10 ** -3), there are subtle differences. 3.1e-3 describes the exact value of 0.0031. 3.1 * (10 ** -3) describes a composite expression that needs to be calculated:

1 > 3.1 * (10 ** -3)

2 0.0031000000000000003

Floating point arithmetics does not even make this expression exact.

If you need precise values, you have two options: one is rounding or truncating the result, and the other is to convert the floating point operands to integer numbers. For instance, instead of 0.25 dollars, you can write 25 cents. This works when you always expect the same number of precision after the decimal point.

Let’s see an example for rounding:

1 > 0.1 + 0.2

2 0.30000000000000004

3

4 > Number( 0.1 + 0.2 ).toFixed( 1 );

5 0.3

In the above example, the precision of the result is fixed to one decimal point.

The division 0 / 0 or using mismatching types creates a special number called not a number or NaN. Ironically, we will soon see that the type of the NaN value is number.

1 > 0 / 0

2 NaN

3

4 > 'ES6 in Practice' * 2

5 NaN

The latter is interesting to Python users, because in Python, the result would have been 'ES6 in PracticeES6 in Practice'. JavaScript does not work like that.

There is another interesting numeric value: Infinity.

1 > 1 / 0

2 Infinity

3

4 > Infinity * Infinity

5 Infinity

6

7 > -1 / 0

8 -Infinity

9

10 > 1e308

11 1e+308

12

13 > 1e309

14 Infinity

JavaScript registers very large numbers as infinity. For instance, ten to the power of 309 is represented as infinity. Division by zero also yields infinity.

Let’s see some strings.

1 > 'ES6 in ' + 'Practice'

2 "ES6 in Practice"

Exercise 10. Determine the type and value of the following numbers:

(1 - 1) / 0(1 - 1) / 1 * 05e05 ** 0 / 05 ** (0 / 0)

Strings and escape sequences

Moving on to string data:

1 > 'ES6 in ' + 'Practice'

2 "ES6 in Practice"

The plus operator concatenates strings. Concatenation means that you write the contents of two strings after each other. Concatenation means that you join the values on the left and on the right of the concatenation operator (+).

A frequent question is, how to write quotes inside a string if quotes represent the boundaries of a string. In JavaScript, there are multiple solutions:

1 // Solution 1:

2 console.log( '--- "This is a quote" ---' );

3

4 // Solution 2:

5 console.log( "--- 'This is a quote' ---" );

6

7 // Solution 3:

8 console.log( "--- \"This is a quote\" ---" );

You can use any number of double quotes inside single quotes, and any number of single quotes inside double quotes. However, using a single quote inside a string defined using single quote would mean that we terminate the string. The same holds for using a double quote inside a string defined using double quotes.

As both single quotes and double quotes are used frequently, the need arises to use both the single quote and the double quote characters inside a string at any time. We can do this by escaping the quote using the \ (backslash) character.

Examples for escape sequences:

-

\'and\": single or double quote characters. In JavaScript, escaped quotes do not start or terminate a string. -

\n: newline character. We can put a line break in the string, making the character after\nappear on the next line. -

\\: as the backslash character creates an escape sequence, it is a special character itself and has to be escaped. The first backslash tells the JavaScript interpreter that a special character is coming. The second backslash says that this character is the backslash. This escape sequence is important to keep in mind when describing Windows file paths in JavaScript or node.js:

1 > console.log( `c:\\js\\hello.js` )

2 "c:\js\hello.js"

Multiline strings can be created using template literals. This comes handy when saving HTML markup in a string:

1 > console.log( `

2 <p>

3 paragraph

4 </p>

5 <ul>

6 <li>first list item</li>

7 <li>second list item</li>

8 </ul>

9 ` );

The above expression prints the text in-between backticks, including the newline characters. The usage of template literals is an advanced topic, we will not deal with them in this chapter.

Exercise 11. Write the following JavaScript strings in the console of your developer tools:

- “JavaScript is easy”, at least until it’s not.

- Save everything to the

C:\Documentsfolder. - Write the following countdown using one

console.logstatement:

1 3

2 2

3 1

4 START!

Strings are immutable which means that their value cannot be changed. The word immutable comes from the fact that strings cannot be mutated. If strings were mutable, we would be able to change the b character in the 'abc' string without creating a new string. In reality, in order to make an 'aXc' string from an 'abc' string, we need to create a new string from scratch.

Similarly, the result of "a" + "b" is a brand new string: "ab". Even after the result is created, "a" and "b" stay in memory. This is why strings are immutable in JavaScript.

If any of the operands of plus is an integer, while the other operand is a string, then the result becomes a string. JavaScript automatically converts the operands of an operator to the same type. This is called automatic type casting:

1 > 1 + '2'

2 "12"

3

4 > '1' + 2

5 "12"

Rules may become confusing, so don’t abuse automatic type casting. Most software developers do not know these rules by heart, as it generally pays off more to write code that is obvious and understandable for everyone.

Examples:

1 > 1 + +"2" // +"2" gives a sign to "2", converting it to a number

2 3

3

4 > 1 + Number("2")

5 3

6

7 > 1 + Number.parseInt( "2", 10 )

8 3

9

10 > 1 + Number.parseInt( "2" )

11 3

All conversions work. The first relies on giving a sign to a numeric string which converts it to a number. Then 1+2 becomes 3. The second type cast is more explicit: you use Number to wrap a string and convert it to a number.

I recommend using the third option: Number.parseInt with a radix. parseInt converts a string into a number. The second argument of parseInt is optional: it describes the base in which we represent the number. Most of the time, we use base 10 values.

Let’s see some more Number.parseInt values:

1 > Number.parseInt("ES6 in Practice")

2 NaN

3

4 > Number.parseInt( "10", 2 )

5 2

6

7 > Number.parseInt( "a" )

8 NaN

9

10 > Number.parseInt( "a", 16 )

11 10

Strings that do not start with a number are often NaN. "10" in base 2 is 2. The character "a" is not interpreted in base 10, its value is NaN. The same "a" character in base 16 is 10.

Number.parseInt recognizes the starting characters of a string as integer numbers, and throws away the rest:

1 Number.parseInt( "1234.567 89" )

2 1234

The dot is not a character present in integer numbers, so everything after 1234 is thrown away by Number.parseInt.

You can also use Number.parseFloat to parse floating point. It parses the floating point number until the terminating space:

1 Number.parseFloat( "1234.567 89" )

2 1234.567

Exercise 12. Select the values out of the following list that have the type number.

+"1"Number.parseInt("")Number("1")1 + "1""1" + 11 + +"1"

Exercise 13. Determine the value of the following expressions:

Number.parseInt( "1.25" )Number.parseInt( "1 2" )Number.parseInt( "5", 2 )Number.parseInt( "15", 2 )Number.parseInt( "f", 16 )Number.parseInt( "ES6" )Number.parseInt( "ES6", 16 )

The boolean type

Let’s see some booleans values. Booleans are either true or false.

The ! operator symbolizes negation. !true becomes false, while !false becomes true.

1 > !true

2 false

3

4 > !false

5 true

An arbitrary value can be converted to boolean using the Boolean function:

1 > Boolean(0)

2 false

3

4 > Boolean(1)

5 true

6

7 > Boolean(2)

8 true

9

10 > Boolean(null)

11 false

The !operator not only negates a value, but also converts it to a boolean. For instance, the negation of a string can be described as follows:

- the empty string (

"") is evaluated asfalseby default in a boolean expression. Negating this value yieldstrue. - An arbitrary at least one character long string is evaluated as

truein a boolean expression. Negating this value yieldsfalse.

1 > !""

2 true

3

4 > !" "

5 false

In JavaScript, we differentiate between truthy and falsy values. These values are not necessarily booleans. Their value only becomes true or false after a type conversion.

A truthy value is a value

vfor whichBoolean(v)istrue. Example truthy values are: nonzero integers, strings containing at least one character. A falsy value is a valuewfor whichBoolean(w)isfalse. Example falsy values are: empty string,0,null,undefined.

Question: Why do we need type conversion using the Boolean function?

Answer: Because otherwise automatic type conversion would produce unintended results. For instance, in the expression 2 == true, both sides of the comparison are converted to numbers. As the value of Number(true) is 1, the 2 == 1 expression is evaluated to false:

1 2 == true ---> 2 == Number(true) ---> 2 == 1 ---> false

2

3 2 == false ---> 2 == Number(false) ---> 2 == 0 ---> false

Furthermore, null and undefined are neither true, nor false:

1 > null == true

2 false

3

4 > null == false

5 false

6

7 > undefined == true

8 false

9

10 > undefined == false

11 false

However,

-

Boolean( null )andBoolean( undefined )are bothfalse -

!nulland!undefinedare bothtrue -

!!nulland!!undefinedare bothfalse

Similarly to the Boolean function, double negation also converts an arbitrary value into boolean:

- if

vis truthy, then!visfalse, and!!vistrue - if

wis falsy, then!wistrue, and!!wisfalse

Examples:

1 > !!""

2 false

3

4 > !!"a"

5 true

6

7 > !!0

8 false

9

10 > !!1

11 true

12

13 > !!NaN

14 false

15

16 > !!Infinity

17 true

18

19 > !!null

20 false

21

22 > !!undefined

23 false

We can compare two numbers with >, >=, ==, ===, <=, <. We will discuss the difference between == and === soon. For the rest of the operators, the result of the comparison is a boolean.

1 > 5 <= 5

2 true

3

4 > 5 < 5

5 false

6

7 > !(5 < 5) // ! stands for negation. !true = false, !false = true.

8 true

The = symbol is not used for comparison. It is used for assigning a value to a variable (see later).

For values a and b, a == b is true if and only if both a and b can be converted to the same value via type casting rules. This includes:

-

null == undefinedis true - If an operand is a string and the other operand is a number, the string is converted to a number

- If an operand is a number and the other operand is a boolean, the boolean is converted to a number as follows:

truebecomes1, andfalsebecomes0.

Don’t worry about the exact definition, you will get used to it.

For values a and b, a === b is true if and only if a == b and both a and b have the same types.

1 > 5 == '5' // '5' is converted to 5

2 true

3

4 > 5 === '5' // types have to be the same

5 false

6

7 > 0 == '' // '' is converted to 0

8 true

9

10 > 0 === '' // types have to be the same

11 false

12

13 > NaN == NaN // I know... just accept this as something odd and funny

14 false

The negation of == is !=. Read it as is not equal to. For instance, !(a == b) becomes a != b. It is time mentioning that you are free to use parentheses to group your values and override the default priority of the operators.

The negation of === is !==.

1 > 5 != '5'

2 false

3

4 > 5 !== '5'

5 true

Exercise 14: Choose the values that (1) are true, (2) are truthy.

1"""false"!!"false"0 == ''0 === ''0 != !10 !== !11 != !11 !== !1nullundefined-

null == undefined null === undefined

So far, all operators have been unary or binary meaning that they bind one or two values:

- the expression

5 + 2has the operands5and2 - the expression

+'2'has the operand'2'

Recall that operators bind their operands. Some operators are said to bind stronger than others. For instance, multiplication binds stronger than addition:

1 5 * 2 + 2 ----> 10 + 2 ----> 12

Also recall that is possible to override the precedence of the operators with parentheses:

1 5 * (2 + 2) ----> 5 * 4 ----> 20

There is one ternary operator in JavaScript.

The value of a ? b : c is:

-

bifais truthy -

cifais falsy

It is important to note the difference between 2 == true and !!2.

1 > 2 == true // true is converted to 1

2 false

3

4 > !!2 // 2 is a truthy value

5 true

6

7 > 2 == true ? 'the condition is true' : 'the condition is false'

8 "the condition is false"

9

10 > !!2 ? 'the condition is true' : 'the condition is false'

11 "the condition is true"

I have seen the nastiest bug in my life in a code, where a condition was in a format num == true. As I never felt like learning boring definitions, my lack of knowledge shot me in the foot, because I assumed the opposite conversion in 2 == true. I can save you some headache by highlighting this common misconception. In 2 == true, true is converted to 1, and not the other way around.

null, undefined, symbol types

Null, undefined, and Symbols are primitive types.

Null represents an intentional absence of a primitive or composite value of a defined variable.

Undefined represents that a value is not defined. We will deal with the difference between null and undefined later.

A Symbol() is a unique value without an associated literal value. They are useful as unique keys, because Symbol() == Symbol() is false. Imagine a symbol as a unique key that opens one specific lock, in a world, where each created key is different from all other keys previously created. At this stage, just accept that symbols exist. You don’t have to use them for anything yet.

1 > null

2 null

3

4 > undefined

5 undefined

6

7 > void 0

8 undefined

9

10 > Symbol('ES6 in Practice')

11 [object Symbol] {}

The value undefined can also be created using the void prefix operator.

Symbols can have a string description. This string description does not have an influence on the value of the symbol:

1 > Symbol('a') == Symbol('a')

2 false

Exercises

Exercise 15: Without running the code, determine the values written to the standard output:

1 // A. Arithmetics

2 console.log( 2*2+4 );

3

4 // B. Ternary operator

5 console.log( 3 % 2 ? 'egy' : 'nulla' );

6

7 // C. Not a Number

8 console.log( (0/0) == NaN );

Once you are done, verify your answers by running the code.

Exercise 16: Convert the following hexadecimal (base 16) values into base 10 and base 2: 0, F, ff, FFFFFF, 99, 10.

Hint: you can convert a value from decimal (base 10) into binary (base 2) in the following way:

1 Number( 2 ).toString( 2 );

2 // --> "10"

3

4 Number( 3 ).toString( 2 );

5 // --> "11"

Exercise 17: Without evaluating the expression, estimate the difference of the base 10 value 2 ** 24 and the hexadecimal value FFFFFF. Create a JavaScript expression that calculates this difference.

Exercise 18: Which data type would you use to model the following data? In case you chose a number type, choose whether you would use an integer or a floating point.

- your name

- your bank account number (assuming it only contains digits)

- your age

- whether you are over 18 or not

- the price of a book is 9 dollars 95 cents

Variables: let, const, and var

In the first few sections, we learned how to use datatypes and how to perform operations on different types of data. However, based on our current knowledge, if we want to perform the same calculation twice in our code, we have to manually copy either the formula or the result. Variables help us automatize and simplify this process by enabling us to access the result of an operation within our code.

First of all, in the below example, you have to know that console.log may print any number of arguments separated by commas. In the console, the values appear next to each other separated by a space.

1 > console.log( 1, 2, 3 )

2 1 2 3

Open the console of Google Chrome by right clicking on a website, selecting Inspect from the context menu, and then selecting the Console tab. In the console, you can type the following expressions:

1 > 1

2 1

3

4 > 2 + 3

5 5

6

7 > 'JavaScript'

8 "JavaScript"

9

10 > JavaScript

11 Uncaught ReferenceError: JavaScript is not defined

12 at <anonymous>:1:1

While in the first three cases you get two integer and one string results, in the fourth case, you get a reference error. This error appears, because JavaScript is a variable, and this variable had not been created in the code.

Before creating this variable, let’s clarify what a variable is. In computer programming, variables are like drawers, where we store values.

The let keyword

We can create variables with the let keyword. Think of a variable like a drawer. Let declares a variable, which means to you that a drawer is created with a handle. Declaration is a process that creates a drawer, and hands the key of the drawer to us so that we can access its contents.

1 let myDrawer;

You can put a value in your drawer:

1 myDrawer = '$1.000';

In order to access the value, you have to grab the handle of the drawer and open it. In this example, you have a drawer called myDrawer. It contains a string written '$1.000' on it. To access your thousand bucks, you have to open the drawer:

1 > myDrawer

2 '$1.000'

You can assign an initial value to your variable with the = sign. This is called assignment, because we assign a value to a variable. The first assignment in the lifecycle of a variable is called definition or initialization.

The declaration and initialization steps can be combined in one step. Let’s create a second drawer, where we both declare and initialize a variable:

1 let mySecondDrawer = '$500';

Initialization can occur either in the same statement where you declared the variable (see declaredAndDefined), or after the declaration (see declaredButOnlyLaterDefined). You may access a declared variable even if you have not initialized it. Its value becomes undefined.

1 let declaredAndDefined = 5;

2

3 let declaredButOnlyLaterDefined;

4 declaredButOnlyLaterDefined = declaredAndDefined ** 2;

5

6 let declaredButNotDefined;

7

8 console.log(

9 declaredAndDefined,

10 declaredButOnlyLaterDefined,

11 declaredButNotDefined

12 );

- The variable

declaredAndDefinedis declared on the same line where it is defined - The variable

declaredButOnlyLaterDefinedis only defined later in another line - The variable

declaredButNotDefinedis not defined at all, therefore, its value becomesundefined

Let’s see what happens if we move the line declaredButNotDefined below the console.log statement.

1 let declaredAndDefined = 5;

2

3 let declaredButOnlyLaterDefined;

4 declaredButOnlyLaterDefined = declaredAndDefined ** 2;

5

6 console.log(

7 declaredAndDefined,

8 declaredButOnlyLaterDefined,

9 declaredButNotDefined

10 );

11 // The following error message is displayed:

12 // ReferenceError: deklaraltDeNemDefinialt is not defined

13

14 let declaredButNotDefined;

If you execute the above code, a ReferenceError should be displayed while executing the console.log statement. This is because the following sequence of events: you ask for the contents of your post box in the post office. However, the box you are asking for does not exist in the post office. This box is only accessible once you create it using the statement let declaredButNotDefined.

1 console.log( declaredButNotDefined ); // ReferenceError

2

3 let declaredButNotDefined;

Constants

Constants behave in a similar way as variables. Constants can be created using the const keyword:

1 const PI = 3.14;

The value of a constant cannot be changed later:

1 PI = 2;

2 Uncaught TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.

As the value of constants stay unchanged, they have to be initialized in the same statement where they are declared. If we forget this necessary step, we get an error message:

1 const c;

2 Uncaught SyntaxError: Missing initializer in const declaration

Scope of a variable

The scope of a variable shows where the variable is visible and where it is not.

In JavaScript, there are many different scopes available:

- Global scope

- Block scope (

let,const) - Function scope (

var) - Lexical scope (see later)

- Module scope (we will not deal with this scope here)

In most programming languages, the first two scopes are available. Function scope is a unique feature of JavaScript. Since the 2015 version of JavaScript, ES6 (or ES2015), function scope is losing its popularity, as the well known block scoped let and const variables emerged.

Regarding block scope, blocks can be created anywhere in your code. Blocks are created using braces ({ and }):

1 {

2 // This is a block

3 }

Variables created using let and const are only visible inside the block where they are created:

1 {

2 let box = 5;

3 console.log( box );

4 }

The above code displays the value of box.

1 {

2 let innerBox = 6;

3 }

4 console.log( innerBox );

In the above code segment, we get a ReferenceError as soon as we reach the console.log statement:

1 VM124:4 Uncaught ReferenceError: belsoDoboz is not defined

This is because the innerBox is not visible from outside the box.

Global scope

Similarly to other programming languages, JavaScript also has global variables. For instance, you have already used the global console variable to log messages. Besides console, open the Google Chrome developer tools console to explore other global variables:

1 > document.location.href

2 "http://zsoltnagy.eu"

3

4 > document.location.host

5 "zsoltnagy.eu"

6

7 > screen.width

8 1920

9

10 > let globalVariable = true

11 true

12

13 > globalVariable

14 true

15

16 > secondGlobalVariable = true

17 true

18

19 > secondGlobalVariable

20 true

As you can see, it is possible to create global variables in the global scope. It does not matter if you use let, const, or a var (see later) keyword to create these variables, or you just write an assignment.

In case of an assignment, the following happens:

- The program checks if there is a variable declared locally in the same block (

let,const) or function (var). - if not, the program checks blocks and functions encapsulating the block or function, where our variable was declared from inside - out. This is the process of accessing the lexical scope, and we will deal with this later in depth.

- If there are no variables defined in the lexical scope, the global scope is accessed, a global variable is created, and its value is set to the value of the assignment.

In the following example, we will only use blocks for simplicity, as we have not learned how function scope works.

1 // first file:

2

3 {

4 let firstBox = 1;

5 {

6 firstBox = 2;

7 secondBox = 3;

8 console.log( firstBox, secondBox );

9 }

10 }

If we execute the above code, the values 2 3 are printed to the console. The variable firstBox exists in the block encapsulating the block we are in. The variable secondBox was created using an assignment, and there are no var, let, or const variables declared with this name. Therefore, this variable exists in the global scope.

Now let’s suppose the contents of the first file have been loaded, and we also load the following code segment titled second file:

1 // second file:

2

3 {

4 let firstBox = 4;

5 {

6 console.log( firstBox, secondBox );

7 }

8 }

Once we execute this code, the values 4 3 are printed. The variable firstBox is defined in the block outside the block of the console.log. The variable secondBox is global, and it was created when loading firstFile. The secondBox variable is from now on shared across all files that we load.

1 // third file:

2 console.log( secondBox );

Executing this code also has access to the secondBox global variable.

1 // fourth file:

2 console.log( firstBox );

The result of loading the fourth file is a ReferenceError, because firstBox does not exist inside this scope: it only exists within the block it was defined in first file and second file.

1 VM5519:1 Uncaught ReferenceError: firstBox is not defined

2 at <anonymous>:1:14

Using global variables is not advised. Most often the time, global variables are created because of a mistake from a developer. Remember, if you forget the let, const, or var keywords in front of a variable assignment, you create a global variable.

The var keyword and function scope

In order to fully understand how the var keyword works, you need to know what functions are. We will learn functions later. For now, it is enough if you accept that variables declared using var are visible inside a function.

Functions can be created using the function keyword:

1 var globalBox = 2;

2 function scope() {

3 var functionScopedBox = 1;

4 console.log( globalBox );

5 }

6

7 scope(); // we call the function to execute its content

8 console.log( globalBox );

9 console.log( functionScopedBox );

The globalBox variable is accessible from everywhere in the code. However, when console logging the functionScopedBox variable in the last line, we get the following error message:

1 Uncaught ReferenceError: functionScopedBox is not defined

1 {

2 var box = true;

3 }

4 console.log( box );

This code is executed without problems, and the variable created inside the block is accessible also outside the block. This is a direct consequence of box being function scoped. As there are no functions encapsulating box, it is global scoped.

Naming variables

Variables should be named in a descriptive way. We need to use the name of the variable to describe what kind of data it stores. A good variable name is like a good comment. Best practices for coming up with a good variable name include:

- the variable describes its content in the best possible way,

- from all possible variable names, choose the shortest name

For instance, out of invoiceSum and invoiceItemSum, the former perfectly grasps the essence of what the variable stores. This is because it is obvious that an invoice contains items without grasping this piece of information in the name of the variable.

It is common practice to start writing variable names using lower case letters. If the variable name contains multiple words, we concatenate them as one word and capitalize the first letter of each word starting from the second word. This variable naming is called camel case (camelCaseVariable).

Creating multiple variables in one statement

One programming best practice is to create all variables we use later to describe a procedure or function, and then perform all the operations on these variables. Example:

1 let name = "Zsolt";

2 let website = "zsoltnagy.eu";

3

4 console.log( name, website );

5 // other operations...

We can abbreviate the variable declarations by using a comma:

1 let name = "Zsolt",

2 website = "zsoltnagy.eu";

Similarly, we can also declare variables and define them later:

1 let name, website;

2

3 name = "Zsolt";

4 website = "zsoltnagy.eu";

Exercises: let, const, var

Exercise 19: Without running the code, determine what is written to the standard output:

1 let a;

2 console.log( 'a: ' + a );

3 a = 5;

4 console.log( 'a: ' + a );

Exercise 20: Without running the code, determine what is written to the standard output:

1 let a = 5;

2 {

3 let a = 2;

4 a += 1;

5 console.log( 'a: ' + a );

6 }

7 console.log( 'a: ' + a );

Exercise 21: Without running the code, determine what is written to the standard output:

1 let a = 5;

2 {

3 console.log( 'a: ' + a );

4 let a = 2;

5 }

Exercise 22: In a previous section, we calculated the value of the FF hexadecimal number in base 10 and base 2. Change the code below such that we only run the Number.parseInt( 'FF', 16 ) calculation once. Hint: use variables.

1 console.log(

2 'FF in base 10:',

3 Number.parseInt( 'FF', 16 ),

4 '\nFF in base 2:',

5 Number.parseInt( 'FF', 16 ).toString( 2 )

6 );

Exercise 23: Continue the previous exercise, and suggest another modification to introduce a variable that eliminates a duplicated calculation.

Exercise 24: Which variable names follow good naming conventions in real life software?

variablenowTimestampfirstParametereurodollarrate

Arrays

An array is an ordered list of items. The items may be of any type. You know, in most post offices, there are hundreds or thousands of post boxes. Each post box may or may not contain something. Each post box has a numeric handle. Post box 25 may be your box. You unlock it, grab its handle, and access its contents.

The trick is that in case of arrays, you have to imagine the post boxes with handles called keys of 0, 1, 2, and so on. Typically, arrays have continuous keys.

1 let days = [ 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday' ];

If you are looking for post box 3 among the days post office, you get Thursday, because Monday is the 0th element, Tuesday is the 1st element, Wednesday is the 3rd element, and Thursday is the 4th element of the array.

Arrays do not have to contain elements of the same type. We can place strings, null, undefined, symbols, objects, and other arrays in the array:

1 let storage = [ 1, 'Monday', null ];

According to an joke, Bill Gates once visited a lower grade class and asked children to start counting to ten. One of the children stood up and said, one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten. Bill Gates thanked for the efforts of the kid and asked someone else. A second kid stood up and started counting: one, two, three, four… Bill Gates already knew the result, so he thanked the second student for his efforts and asked someone else. Then came a third kid forward and started counting: zero, one, two, three… and this is when the kid got hired by Microsoft.

The takeaway of this story is that each element of the array can be accessed using an index starting from zero:

1 > days[0]

2 'Monday'

3

4 > days[4]

5 'Friday'

6

7 > days[5]

8 undefined

In the third example, we indexed out of the array.

Arrays have lengths:

1 > days.length

2 5

We often need to access the last element of an array. For instance, the days array has a length of 5. Indexing of an array starts with 0. Therefore, the last index is 4. In general, the index of the last element equals the length of the array minus 1:

1 > days.length - 1

2 4

3

4 > days[ days.length - 1]

5 'Friday'

Remark: In some other languages, such as Python, we can refer to the last element of a list using the index

-1. In Python,days[-1]is the same asdays[len(days) - 1]. The index of-1is interpreted as the first element counting backwards from the end of the list. In JavaScript, we cannot use this way of indexing.

You can add elements to the beginning and to the end of the array.

1 > days.push( 'Saturday' );

2

3 > console.log( days ); // add 'Saturday' to the end

4 ["Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday", "Saturday"]

5

6 > days.unshift( 'Sunday' ); // add 'Sunday' to the beginning

7 ["Sunday", "Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday", "Saturday"]

You can also remove these elements from the array: - Pop removes the last element from the array and returns it. - Shift removes the first element from the array and returns it.

1 > let element = days.pop();

2 > console.log( element, days );

3 "Saturday" ["Sunday", "Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday"]

4

5 > let secondElement = days.shift();

6 > console.log( element, days );

7 "Sunday" ["Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday"]

Similarly to objects, you can delete any element from the array. The value undefined will be placed in place of this element:

1 > delete days[2]

2 ["Monday", "Tuesday", undefined, "Thursday", "Friday"]

The values of an array can be set by using their indices, and equating them to a new value. You can overwrite existing values, or add new values to the array. The indices of the added values do not have to be continuous:

1 > days[2] = 'Wednesday';

2 > days[9] = 'Wednesday';

3 > console.log( days );

4 ["Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday", "Thursday", "Friday", undefined, undefined, undef\

5 ined, undefined, "Wednesday"]

Strings also provide access to their characters as if a string was an array of characters:

1 const str = 'Hello';

2

3 console.log( str[1], str[4], str[5] );

4 // --> e o undefined

The element at index 1 is the character e. The element at index 4 is the fifth character of the string, o. If we tried to access the element at index 5 of the string, we would get the sixth character of the array. This would make us index out from the array though. In JavaScript, indexing out from an array or string is possible: we just get an undefined value.

Our last language construct is the slice method. Unsurprisingly, this method slices an array, returning a new array with a continuous subset of elements.

We can specify the beginning of the slice as follows:

1 let days = [ 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday' ];

2

3 > console.log( days.slice( 1 ) )

4 [ 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday' ]

5

6 > console.log( days.slice( 4 ) )

7 [ 'Friday' ]

The beginning of the slice is the index of the first element we want to see in the slice. This number can also be zero, in which case we make a shallow copy of the original array:

1 let daysCopy = days.slice( 0 );

2 daysCopy[0] = '???';

3

4 console.log( days );

5 // [ 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday' ]

6

7 console.log( daysCopy );

8 // [ '???', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday' ]

If you know the difference between a shallow copy and deep copy, be aware that slice creates the former. Otherwise, at this stage, it is enough to understand that slice always returns a new array, copying its elements.

For a useful slicing operation, we also need a way to specify the end of the slice. In JavaScript, the end of the slice is specified as the index of the first element we do not want to see in the array.

1 // Monday - Wednesday:

2 // - we start with the 0th element,

3 // - the first element we don't want is at index 3

4 > days.slice( 0, 3 )

5 [ 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday' ]

6

7 // Thursday:

8 // - we start at index 3

9 // - the first element we don't want is at index 4

10 > days.slice( 3, 4 )

11 [ 'Thursday' ]

Specifying the end of the slice is optional. This means, days.slice( 1 ) is the same as days( 1, days.length ).

Remark: as many developers learn Python, it’s worth noting that Python uses the colon in the index for slicing.

days[0:3]is the same asdays( 0, 3 ). Whenever we have a zero on any side of the column in Python, that zero is optional:days[:3]is the same asdays[0:3],days[2:]is the same asdays.slice( 2 )in JavaScript, anddays[:]is the same asdays.slice( 0 )in JavaScript. We can see how similar some programming languages are to each other. You are better off learning the thought process, and then the syntax will be easy.

As with most topics, bear in mind that we are just covering the basics to get you started in writing code. There are multiple layers of knowledge on JavaScript arrays. We will uncover these lessons once they become important.

Exercises: Arrays

Exercise 25: Without executing the code, determine what is written to the console:

1 let array = [ 7, 15, 32, 9, '3', '11', 2 ];

2

3 // A.

4 console.log( array[3] );

5

6 // B.

7 console.log( array[7] );

8

9 // C.

10 console.log( array.pop() );

11

12 // D.

13 console.log( array );

14

15 // E.

16 console.log( array.shift() );

17

18 // F.

19 console.log( array );

20

21 // G.

22 console.log( array.push( 6 ) );

23

24 // H.

25 console.log( array );

Exercise 26: Without executing the code, determine what is written to the console:

1 const days = [

2 'Monday',

3 'Tuesday',

4 'Wednesday',

5 'Thursday',

6 'Friday'

7 ];

8

9 console.log( days[2] );

10 console.log( days[1][2] );

11 console.log( days[ days.length - 1][1] );

The Object type

This section will introduce the Object type. We will only learn the basics here.

An object is data structure with String or Symbol keys and arbitrary values. Imagine it like a machine that accepts a key, and gives you a value. Some people call this data structure associative array, others call it hashmap. These names may sound fancy, but essentially we mean the same damn thing.

Side note: we will only deal with String keys for now. Symbol keys are also allowed for strings. This is an advanced topic, you will learn it later.

An associative array is like human memory. In order to get access to a memory, we need an association, which is a handle or a key. This key unlocks the memory by providing access to it. The address of associative memory is therefore content. In JavaScript, we will use strings to describe this content.

1 let author = {

2 name: null,

3 website: "zsoltnagy.eu",

4 age: 35

5 }

6

7 console.table( author );

Run the above code in the console of Google Chrome developer tools. You can see that console.table enumerates the keys and values of the author object in a tabular format.

Similarly, console.log( author ) also logs the author object, but in this log, we need more clicks to read the keys and values.

The members of the author object can be accessed using a dot. For instance, author.name gives you read and write access to the name property of the author object. For instance, we can read the author.name value and log it using console.log( author.name ). To change the value of the name property, we have to wrtie author.name = 'Zsolt'.

1 author.name = "Zsolt";

2 console.log( author.name, author.website )

3 // Prints: Zsolt zsoltnagy.eu

It is possible to delete members of an object using the delete operator:

1 delete author.name

2 console.log( "Author name: ", author.name )

3 // Prints: Author name: undefined

If a field in an object is deleted or not even declared, the value of this field is undefined.

1 let o = {};

2

3 > o.name

4 undefined

An object contains fields. A field in an object can be referenced in the following ways:

- the already introduced dot notation:

object_name.member_name - bracket (associative array) notation:

object_name[ string_or_symbol_value ]

Let’s explore how we can select a member of an object if the corresponding key is in a variable:

1 let key = 'website';

2

3 // How can we select author.website?

The solution is to use the bracket notation and get author[ key ]. The value inside the brackets is converted to a key.

1 author[ key ]

2 // Prints: zsoltnagy.eu

We already know that the key of an object is a string. If we supply a key of different type inside the brackets, then this key is automatically converted to a string:

1 const key = 1;

2 const street = {};

3

4 street[ key ] = 'house';

5

6 console.log( street );

After executing the above code, the value { "1": "house" } is printed to the console.

A member of an object can be another object:

1 let car = { numberPlate: 'ABC123' };

2

3 let garage = {

4 size: 1,

5 parking: car

6 }

Here we can see that the garage has an integer size and an object propery called parking.

We typically build objects using braces by enumerating key-value pairs inside an opening brace and a closing brace. Once an object is built, we can add more properties to it:

1 garage.owner = { name: 'Zsolt' };

In the above example, we changed the value of garage.owner from the default undefined to an object.

We saw that we can refer to members of an object in two ways:

- dot notation: the value of

garage[size]is1, - bracket notation:

garage['size']is1.

The two notations are equivalent.

It is important to note that in the bracket notation, you need a value that can be converted to a string and does not throw an error. Therefore, if you try to retrieve garage[ nonExistingKey ], you get an error.

We will learn a lot more about objects later.

Exercises: objects

Exercise 27: Create an object that models a lottery poll. A lottery poll is defined by its time. We model this time using a string of format "2020-11-25 18:20". We also store the prize, which is also a string of form "20.000.000$". We also store five numbers that can range between 1 and 90. These values are stored in an array.

Exercise 28: Suppose the following object is given:

1 let ticket = {

2 from: {

3 airport: 'HAN',

4 date: '2020-11-05',

5 time: '09:40'

6 },

7 to: {

8 airport: 'AAA',

9 date: '2020-11-05',

10 time: '11:25'

11 },

12 name: 'Java Script',

13 passport: '123456XY'

14 }

Using this object, write the following values to the console:

- start and arrival time and date,

- name,

- passport id,

- airport code of the destination.

Exercise 29: Create an object that contains an infinitely long chain of object references. For instance, if you call your object tree, make sure tree.tree, tree.tree.tree, tree.tree.tree.tree etc. are all available.

1 let tree = { leaf: "fruit" };

2

3 // Write your solution here such that the below logs

4 // all write "fruit"

5

6 console.log( tree.leaf ); // "fruit"

7 console.log( tree.tree.leaf ); // "fruit"

8 console.log( tree.tree.tree.leaf ); // "fruit"

9 // ...

Exercise 30: Suppose there is a safe object. The safe is opened by a secret key combination "123456". Create a reference that unlocks the safe and provide access to the value belonging to the key "123456".

1 let safe = { "123456": "$10.000" };

Exercise 31: We learned that the key of an object can either be a string or a symbol. Suppose that there is a variable declared and defined as let num = 5;. Consider the following code:

1 let num = 5;

2 let o = {};

3

4 o[ num ] = true;

5

6 console.log( o, o[ 5 ], o[ "5" ] );

Run the above code in your console and check the output. Explain what happens to the 5 key in o[ 5 ] that results in the log you saw.

Now let’s create a variable containing the "5" string, and run this code:

1 let text = '5';

2

3 o[ 'text' ] = false;

4

5 console.log( o, o[ 5 ], o[ "5" ] );

Run the above code and explain what happens when querying o[ 5 ].

Exercise 32: Create a map object with keys of the values of array arr. The values belonging to the keys are universally true. Use the console.table function to inspect the map object in Chrome developer tools.

1 let arr = [1, 5, 3, 1];

2

3 let map = {};

4

5 // Write valid JavaScript code in place

6 // of the ____ symbols to add key-value pairs to map.

7 // ____arr[0]____ = true;

8 // ____arr[1]____ = true;

9 // ____arr[2]____ = true;

10 // ____arr[3]____ = true;

11

12 console.table( map );

Exercise 33: Modify the previous exercise such that instead of true, the values belonging to keys arr[0], arr[1], arr[2], arr[3] are their respective indices 0, 1, 2, 3. Before running your code, determine the key-value pairs stored in the object map.

1 let arr = [1, 5, 3, 1];

2

3 let map = {};

4

5 // Write valid JavaScript code in place

6 // of the ____ symbols to add key-value pairs to map.

7 // ____arr[0]____ = 0;

8 // ____arr[1]____ = 1;

9 // ____arr[2]____ = 2;

10 // ____arr[3]____ = 3;

11

12 console.table( map );

Functions

Think of a function like a mathematical function giving you a relationship between input and output variables. If you don’t like maths, think of a function like a vending machine. You give it some coins and a number, and it gives you a bottle of cold beverage.

1 function add( a, b ) {

2 return a + b;

3 }

This function definition describes the relationship between its input variables a and b, and the return value of the function.

The return statement returns the value of the function. When calling the add function with arguments a and b, it computes the value a+b and returns it. Example:

1 > add( 5, 2 )

2 7

Try to modify the input variables. The return value also changes. Try to call the add function with one variable, e.g. add( 5 ), and see what happens.

Functions are useful to create reusable chunks of code that you can call with different arguments. We will write more useful functions once you learn the basics of control structures.

You can also define functions without placing the name between the function keyword and the argument list. This structure is great if you want create a reference to it using a variable. Remember, the variable subtract is a handle to a drawer. This time, your drawer contains a function.

1 let subtract = function( a, b ) {

2 return a - b;

3 }

There is another popular notation first introduced in ES6: the fat arrow notation.

1 let multiply = ( a, b ) => a * b;

The fat arrow describes the relationship between the argument list and the return value. In other words, it expects two values, a and b, and transforms these values to a * b.

Arrow functions are typically used when the input can be transformed to an output that can be calculated using the input variables:

1 function functionName( a, b, ... ) {

2 return value;

3 }

4

5 // conversion:

6 var functionName = ( a, b, ... ) => value;

If there is only one input argument, you may omit the parentheses around it:

1 let square = a => a * a;

All functions can be called using their references:

1 > add( 2, 3 )

2 5

3 > subtract( 2, 3 )

4 -1

5 > multiply( 2, 3 )

6 6

7 > square( 2 )

8 4

When a function does not return anything, its return value becomes undefined:

1 > let empty = function() {}

2

3 > empty()

4 undefined

The JavaScript interpreter always inserts a return undefined; statement at the end of each function. This is the default return value of every function. This default value can be overridden by the developer by specifying a return statement.

Variables inside the function are not the same as variables outside the function:

1 let coins = 5;

2 function addOne( coins ) {

3 coins = coins + 1;

4 return coins;

5 }

6

7 > addOne( coins )

8 6

9 > coins

10 5

The coins variable inside the function is valid inside the scope of the function. It shadows the variable coins outside the function. Therefore, adding one to the internal coins variable does not have any effect on the external value. To see the execution of this code in action, follow this URL.

We learned earlier that variables declared using var are function scoped. Function arguments are also function scoped:

1 let coins = 5; // this is a global variable even if var was used

2 function addOne( coins ) {

3 // the inner coins variable shadows the global coins

4 // only the inner coins variable is accessible

5 coins = coins + 1;

6 return coins;

7 }

When there is a variable both inside and outside a function, the inner variable is said to shadow the outer variable whenever we execute code inside the function. This is what happened to the coins variable. Operations modifying the value of the inner coins variable do not affect the value of the outer coins variable.

Without changing execution of the code, we can safely rename the inner variable to illustrate that the two variables are different and only the inner variable is modified inside the function:

1 let coins = 5;

2 function addOne( innerCoins ) {

3 innerCoins = innerCoins + 1;

4 return innerCoins;

5 }

Exercises: functions

Exercise 34: Let’s recall a possible solution of the number conversion exercise:

1 let hexadecimalValue = 'FF';

2 let baseTenValue = Number.parseInt( hexadecimalValue, 16 );

3 console.log(

4 hexadecimalValue + ' in base 10:',

5 baseTenValue,

6 '\n' + hexadecimalValue + ' in base 2:',

7 baseTenValue.toString( 2 )

8 );

Write a function that expects a string containing a correctly formatted hexadecimal number, converts this hexadecimal value to base 10 and base 2, and console logs the result:

1 > convert( 'ACE' )

2 ACE in base 10: 2766

3 ACE in base 2: 101011001110

Exercise 35: Write a head comment to the function you created in the previous exercise. Head comments describe the parameters, the return value, and a one sentence summary of what the function does. Head comments typically have the following format:

1 /**

2 * One sentence summary of the function

3 *

4 * @param string description of the parameter

5 * @return undefined

6 */Immediately Invoked Function Expression

Be mindful that this section contains a regular JavaScript interview question. The question is:

Question: What is an IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression)?

The short answer is, we create a function and immediately invoke it.

We learned that we can create a function using the function keyword:

1 function f() {

2 console.log( "f() has been executed" );

3 }

In order to invoke the function, we need to add two parentheses after the name of the function:

1 f();

2 // Logs: f() has been executed

We can combine the function definition and invocation if we place the () right after the function definition. To do that, we need to put the function definition in parentheses too:

1 (function f() {

2 console.log( "f() has been executed" );

3 })();

4 // Logs: f() has been executed

Don’t forget the parentheses around the function definition. If you omit them, you get an error message:

1 function f() {

2 console.log( "f() has been executed" );

3 }();

4 // Error: Uncaught SyntaxError: Unexpected token )

The name of function f does not have any significance in the code, it acts like a comment. We can safely omit the name f, creating an anonymous function.

1 (function() {

2 console.log( "The function has been executed" );

3 })();

It is also possible to pass parameters to immediately invoked function expressions:

1 (function( text ) {

2 console.log( text );

3 })( "The function has been executed" );

In the parametrized version, you can write any value in place of the string "The function has been executed".

Starting from ES2015, the 2015 specification of JavaScript, immediately invoked function expressions can also be created using arrow functions:

1 ( text => console.log( text ) )( "Done." );

This format is not a surprise, because text => console.log( text ) can be substituted by console.log itself. It expects a text variable, writes it to the console, and returns undefined. If we make this substitution, we get the following expression:

1 ( console.log )( "Done." );

The parentheses around console.log can also be omitted resulting in:

1 console.log( "Done." );

Exercises: Immediately Invoked Function Expressions

Exercise 36: Create an immediately invoked function expression that expects two numeric parameters and returning the sum of these two parameters. You can assume that the parameters are numbers, you don’t have to check their types.

Variable Scopes and Shadowing

This section will be challenging, therefore, read it multiple times to let the material sink in.

Let’s summarize what we learned about scopes:

1 let global = true; // global variable

2 {

3 let block = true; // block scope

4 }

5

6 (function() {

7 var functionScoped = true; // function scope

8 })();

Global variables are visible everywhere.

Block scoped variables are visible within the block they are created in, but they are not visible outside the block.

The last example is an immediately invoked function expression. This is a function that we immediately invoked using the () symbols. Variables created using var inside this function invocation are visible inside the function, but not outside it.

Let’s see what happens if we nest multiple immediately invoked function expressions:

1 var functionScoped = 'Sun';

2 let x = 1;

3 (function outer() {

4 var functionScoped = 'Moon';

5 (function inner() {

6 console.log( '----Function----' );

7 console.log( 'x: ', x );

8 console.log( 'functionScoped: ', functionScoped );

9 })();

10 })();

After the execution of the program, the following is written on the console:

1 ----Function----

2 x: 1

3 functionScoped: Moon

It does not matter if the x variable is declared using let, var, or const. We could even omit the keyword representing the scope, as either way, x is created in the global scope, therefore, it will be a global variable. Therefore, the value of x is visible everywhere in the code, so in the inner function, we can console log its value.

Inside the inner function, we can access all variables of the outer function, regardless of whether they are declared using var, let, or const, or they come from the outside.

Both in the inner and outer functions, we can access variables that were created in the same scope where the outer function was created. In this specific situation, it’s the global scope.

The above explanation is not complete though. According to the explanation so far, in both outer and inner, we would have access to two functionScoped variables. One has a value 'Moon', while the other has a value 'Sun'. In reality though, we only have access to one of the variables.

If we move outwards from the inner scope, we can only access the closest variable with a given name. In case of functionScoped, this variable is in the outer scope. The functionScoped variable in the outer scope therefore shadows the global functionScope variable.

In other words, the 'Moon' shadows the 'Sun', giving you a total eclipse from the perspective of the inner and outer scopes. This is why we can only see the 'Moon' in the console.log statement in the inner scope.

Based on this explanation, you can have an idea of what lexical scope is for functions. Lexical scope gives you access to

- all variables within a given function,

- all variables in the function containing the scope we are examining recursively,

- if two variables have the same name in a lexical scope, the variable that is defined closest to the scope we are examining shadows all variables with the same name that are outside this scope.

The same explanation holds for block scope:

1 let blockScoped = 'Sun';

2 let x = 1;

3 {

4 let blockScoped = 'Moon';

5 {

6 console.log( '----Block----' );

7 console.log( 'x: ', x );

8 console.log( 'blockScoped: ', blockScoped );

9 }

10 }

Exercises: variable scopes and shadowing

Exercise 37: Without running the program, determine the value written to the console:

1 // Global scope

2 let x = 1;

3 {

4 // block A

5 let x = 2;

6 {

7 // block B

8 let x = 3;

9 }

10 {

11 // block C

12 console.log( x );

13 }

14 }

Exercise 38: Rewrite the code of the previous exercise such that you use var instead of let, and you use immediately invoked function expressions instead of blocks.

The typeof operator

In some cases, we may want to check the type of a value we hold in a variable. To perform this task, we will introduce the typeof operator.

Let’s recall the concept of an operator and an operand:

For instance, in the 2 * 3 operation, the multiplication sign (*) is the operator, and the operands are 2 and 3.

The typeof operator accepts one operand and returns a string. This string describes the type of an object.

1 typeof '' // "string"

2 typeof 0 // "number"

3 typeof true // "boolean"

4 typeof {} // "object"

5 typeof [] // "object"

6 typeof null // "object"

7 typeof undefined // "undefined"

8 typeof Symbol() // "symbol"

There is just one problem: arrays, objects, and the null value have the same type. It would be great if we could differentiate between them. Fortunately, ES6 solves the array problem:

1 > Array.isArray( [1, 2] )

2 true

3 > Array.isArray( {a: 1} )

4 false

Regarding the null value, a simple comparison does the trick:

1 let name = null;

2

3 > name === null

4 true

Functions have the type "function":

1 function two() { return 2; }

2

3 typeof two

4 "function"

Exercises - typeof operator

Exercise 39: Without executing the code, determine the values of the following variables:

1 let a = typeof '';

2 let b = typeof a;

3 let c = typeof x;

4 let d = typeof 25;

5 let e = typeof null;

6 let f = typeof 25 + ' ';

7 let g = typeof (NaN === NaN);

8 let h = typeof null;

9 let i = '' + 1;

10 let j = typeof i;

Requesting Input from the User

When I started programming back in the days, I mainly studied from books, because back in the 90s, I didn’t have access to Internet. I can recall a thick programming book I had. As I worked my way through the examples of the book, I had one question in mind all the way through making progress in the book: how can I get an input from the user?

After a while, I searched for a function that lets me enter an input, and I didn’t find this function at all. I asked myself, if it is so hard to get an input, then why am I learning programming?

Eventually, I had to go to an Internet café to find the answer. In hindsight, I found out that user input was not even considered in the thick book I wrote.

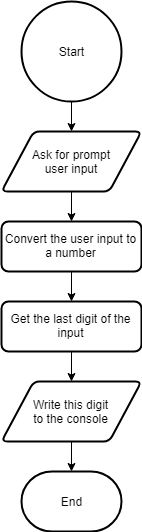

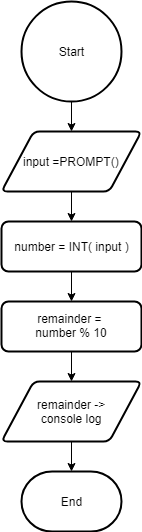

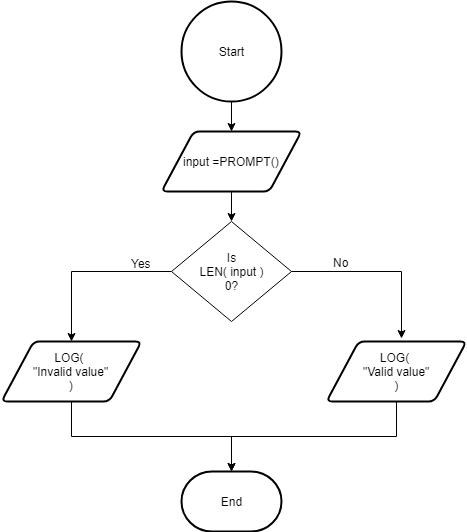

As I recalled these memories, I concluded that I don’t want to create a book, where I leave you wondering about how to enter input. Therefore, in this section, you will learn about two methods to get input from the user. These are:

- Prompt window,

- HTML5 forms.

There are many other ways to get user input, such as an API connection or a direct database connection in case of node.js. A node.js program also helps you process files. However, in this section, we will stick to introducing the capabilities of Prompt windows and HTML5 forms.

Prompt window

You can use the prompt statement to create a window with a textfield and get data from the user:

1 let value = prompt( 'Enter a number' );

Once this expression is executed, a popup appears on screen with the 'Enter a number' message, an input field, and two buttons: OK and Cancel. If you press the Cancel button, the prompt function returns null in the code. If you press the OK button, the prompt function returns the text that the user entered in the input field. If the input field is left empty, the return value after pressing OK becomes the empty string ("").

Suppose that the user entered the value 25. As the prompt function returns a string, this value is available as a string:

1 > console.log( value, typeof value);

2 "25" string

HTML5 Forms

This section only serves as an introduction to how data can be extracted from an HTML page using JavaScript. Our goal here is not deep understanding, but rather illustration of possibilities, so that you know what to expect from JavaScript.

Open a new tab in your Google Chrome browser, and open the developer tools console. Run the following code:

1 document.body.innerHTML = `

2 Age: <input type="text" name="age" class="js-age">

3 <input type="checkbox" class="js-accept-toc" id="accept-toc">

4 <label for="accept-toc">Accept the terms and conditions</label>

5 `;

After running this code, the contents of the website you were viewing got replaced by a textfield and a checkbox. Don’t worry, the change is only effective in your browser, no-one else can see these changes from other computers.

You can modify the value of the textfield and checkbox from the browser. Let’s learn how we can access these values using JavaScript.

We can extract the contents of the Age field in the following way:

1 let age = document.querySelector( '.js-age' ).value