Introduction

The Problem And What This Book Is About

For the past forty years I have been helping high technology organizations in their quest to improve and keep ahead of the competition. During this time I observed millions of dollars spent annually on process improvement initiatives that too frequently fell short of their intended mark. Due at least in part to this situation, today many are turned off and have tuned out when it comes to the multitude of process and performance improvement approaches along with their related hype and buzzwords. Agile [1], CMMI [2], Kanban [3], Lean [4], Six Sigma [5], Lean Six Sigma [6], PSP [7], and TSP [8] to name just a few. We have taken a simple idea and made it far too complex and in so doing have lost the spirit and intent of performance improvement. I have also observed common patterns associated with these past efforts which can shed light on how we can do better at the process of getting better in the future.

My First Goal in this Book

My first goal in this book is to explain why we are facing these problems and how you can get yourself and your organization back on track focused on the things that matter most to both your own personal performance and your organization’s performance. This book is equally about personal and organizational performance.

More About the Problem

Part of the problem we face has been caused by a gap that exists between the theory of performance improvement and the way that theory is being implemented today. As an example, today many organizations that use the CMMI– specifically the high maturity practices– have fallen short of achieving the high value sustainable performance improvements sought [9]. By high value I mean those improvements that address pain points that hurt us the most when we need our performance to be at its best. I am using the CMMI as an example here, but the data presented is reflective of other performance improvement models as well, including Lean Six Sigma [10], and Agile Retrospectives [11], as will be discussed.

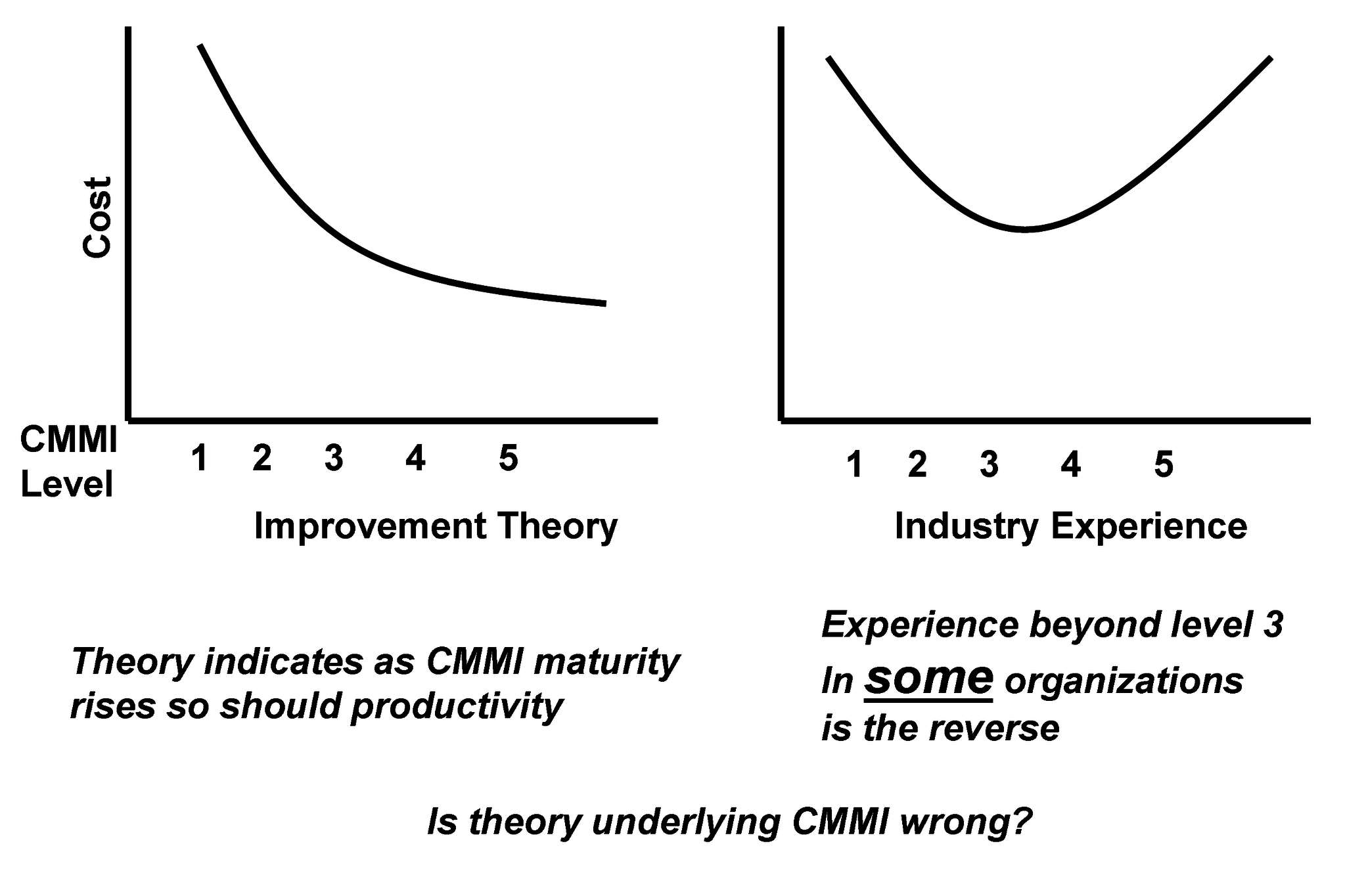

Figure Intro-1 demonstrates the improvement theory underlying the CMMI, alongside what some organizations have actually experienced [12]1. I emphasize the word some because there is also growing evidence indicating high maturity practices can reduce cost. [13] Our focus here is on those organizations experiencing difficulties reaping the most valuable benefits from their performance improvement investments, regardless of their improvement approach. I highlight CMMI High Maturity practices because the intent of these practices is to help organizations improve performance and sustain those improvements.

Figure Intro-1 CMMI Theory and Observations

The graph on the left in the referenced figure demonstrates the theory that as CMMI maturity rises cost should decrease (this assumes the same quality/defect level in the resultant product). The graph on the right demonstrates that after level 3 cost actually rises in some organizations thus degrading, rather than improving, performance. This data was originally provided by a Senior Manager in a CMMI Level 5 organization and there are numerous other sources available supporting similar experiences [14, 15, 16]. This leads to a question:

Is the theory underlying the CMMI wrong?

It is my contention that the theory is not wrong, but as an industry we have not done a good job of translating theory to practice. Or, in other words, we have not done a good job of explaining the theory in simple enough terms so it can be applied easily to everyday situations faced by professionals on the job. Stated another way, the increase in cost observed in the diagram reflects poor CMMI implementation, rather than an error in the CMMI model.

About the Proposed Solution

To achieve high value sustainable performance improvements in the current technology environment we need a culture shift in how performance improvement is viewed and implemented. Organizations need to take a lesson from how great performers really get better at what they do and apply it within their own business context.

Today many organizations use documented process descriptions, comprehensive formal training, and extensive studies and pilot projects to help their people get better at doing their job. While these techniques can help achieve a level of proficiency, historically they have fallen short at helping us achieve and sustain our most valuable potential improvements taking us beyond fundamentals.

How Performance (Process) Improvement Works Today

Often a process 2 improvement effort in an organization begins by assigning a small group of employees to the task. The first pattern I have observed is that this group is usually secluded from the stakeholders who must eventually use the improvement. This is not wrong. Change must be carefully managed so it does not disrupt critical on-going business. But too often the major portion of these improvement investments is expended by people working the effort in isolation from those intended to receive the help. High value sustainable improvement can only result when those who must perform can utilize the improvement in solving their daily challenges. I have also observed many of these efforts in organizations leading to a cycle that seems to move from one fad to the next with little sustainable improvement3 over time to show for the effort expended.

If you work in a large corporation, these observations may not surprise you, but have you given much thought to why these patterns occur, and what could be done differently leading to a more sustainable positive result?

In the book “Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else” [17] the author explores how world class performers move their performance to much higher levels than most people ever achieve through what the author calls “deliberate practice”. “Deliberate practice” is not what most of us were taught about practice when we were young. It is highly demanding mentally, and it is not fun.

A Second Goal in Writing This Book and Why You Should Care

In Chapter One of this book I begin the investigation into what it takes to achieve high value sustainable performance improvement by discussing in more detail the concept of deliberate practice and how it has helped world class performers such as Jerry Rice4, and Bill Gates. But this book is not about how to become another Jerry Rice or Bill Gates.

On the personal side, this is a book that can show you how to get just a little bit better at whatever you want to get better at regardless of your current performance level, and it will show you how to sustain that performance improvement once you have achieved it.

On the business side, organizational process and performance improvements can be broadly grouped into two categories: Technology and major organizational changes looking to the future, and smaller changes that can help practitioners every day.

A second goal in this book is to present the case that the speed of change we are all witnessing in today’s world requires a rebalancing of how organizations view and prioritize their process and performance improvement initiatives across these two broad categories.

This may not sound like a very big goal for a book, but think about what it would mean to you and your organization if everyone just got a little better at what they did today, and tomorrow everyone got a little bit better again.

This book provides practical techniques that have been proven to help individuals and organizations get better and sustain their performance improvements into the future.

The Approach in this Book

Before we jump into the material, let me tell you a little about the approach I took in developing the book. This book is not about any specific performance improvement approach, but it does discuss many popular approaches including the CMMI, Lean Six Sigma, and Agile Retrospectives. My approach is to highlight fifteen (15) fundamentals I have observed common to all successful improvement efforts where sustainable high value performance improvements are achieved. These fundamentals too often get missed by organizations and individuals trying to improve and sustain their improvements.

The intent is not to focus on, or dive too deep into, any specific improvement approach, but to highlight what is common across all of them with respect to the essentials of effective performance improvement.

In this book I share real examples from both my own consulting experiences, a personal performance improvement experience, and stories from high performing athletes and musicians to help you think about performance improvement outside-the-box.

A Third Goal of this Book

A third goal of this book is to share a vision for a framework that can help counter the patterns that may be holding you and your organization back. I am not talking about yet another buzzword, method, or new tool to hype, but rather a simple thinking framework that can help keep you and your organization focused on the fundamentals too often missed.

Summarizing the 15 Fundamentals and Thinking Framework Needs

Below you will find a summary of the 15 fundamentals and the related thinking framework needs in support of each fundamental. In order not to distract the reader from the main flow of the book I have chosen to make observations about this framework in sidebars (noted by “Framework Vision”) in Parts I and II of the book. In these sidebars I explain the framework’s key characteristics, rationale for the characteristics, and connection to the fundamentals.

In Part III of the book I share an example of such a framework that holds promise and I explain how this framework may be able to help organizations achieve and sustain the higher performance they seek.

|

Fundamental One:Training is about helping people understand expectations related to a job. Practice helps you actually do your job, and learn to repeat how you do it, and continue to do it well even under difficult and often unanticipated conditions. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: Our framework envisions practices as living entities reflecting what people actually do. With our vision your practices are built as extensions to a set of essentials that have been widely agreed upon.

Learning to perform a practice effectively requires more than just acquiring knowledge about our processes. It also requires an understanding of the context we must perform within and it requires that we learn how to make rapid and effective decisions that fit within a specific context. Thus, our framework must support these real world needs.

|

Fundamental Two:We each have tendencies toward repeating specific weaknesses, and experience has shown they are often the largest obstacle people and organizations face when trying to sustain higher levels of performance. A critical first step toward sustaining higher performance is to locate areas that contain critical repeating specific weaknesses that hinder your personal or your organization’s performance. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: A key difference with our framework vision from what has been done in the past can be summed up in the phrase “separation of concerns”.

Our goal is to separate the essentials (e.g. what all successful projects should focus on) from extensions (e.g. specific practices, such as those needed to address a specific situation or weakness).

The rationale for this goal is to simplify the management of practices for individuals, and teams allowing them to keep their specific practices up to date reflecting their specific needs based on their specific situation, without having to worry about whether their changes are jeopardizing the essentials, that we all need to be constantly focusing on.

|

Fundamental Three:One of the best ways to keep people motivated and interested in their work throughout their career is to involve them in their own continuous improvement. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: Our framework vision places the professional in charge of their own practices, supports them in identify where changes are needed, and empowers them to make those needed changes. Some fear this approach believing that project pressures may lead personnel to make poor decisions degrading rather than improving their practices. This is one of the reasons why separation of concerns is so important. Separating the essentials from specific practice extensions ensures the essentials are never lost as we make changes to improve and sustain our higher performance.

|

Fundamental Four:You have to figure out your own repeating specific weaknesses if you are to gain the benefits and achieve your own sustainable higher performance. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: While each organization must locate their own unique repeating trouble spots, our vision includes a framework that can help organizations by guiding them to consider areas where trouble has most often been found in the past.

|

Fundamental Five:You should always, as individuals, reduce the number of areas you are focusing on at any one time to between three and seven, ideally closer to three. Organizations can have more, but this should not increase the focus of individual performers. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: Our vision stresses that all changes to your way of working should be accomplished incrementally in small steps supporting fundamental five.

|

Fundamental Six:When selecting areas to measure ensure you have done sufficient analysis (e.g. following real threads) to know you understand the real context and there is high likelihood of findings that will lead to improved performance in the reasonably near future. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: Our framework needs to be a “thinking framework” in the sense that it helps individuals and teams make better decisions related to small timely changes by providing the team with objective data they can use to support their decisions.

|

Fundamental Seven:Some of the most significant impacts to performance start out as seemingly little things that we often fail to notice until it becomes too late to correct. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: Helping practitioners make tough choices where they don’t have enough time to do everything may be the most valuable area where our thinking framework can benefit our teams.

|

Fundamental Eight:When you’ve been doing something wrong for an extended period, the right way may feel wrong for a period of time while you are adjusting to the change. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: We envision the framework helping most at the start of a project (e.g. preparation steps). If the project runs smoothly, its value may diminish as the project proceeds. On the other hand, if the project starts to run into trouble, the value of the framework rapidly rises.

This is because the framework is a monitoring aid. You can liken it to a good referee in a sporting event. In well played games good referees are often not noticed. Their value becomes clear when the trouble starts.

|

Fundamental Nine:Collecting more and more samples of the same data won’t help an organization improve or sustain higher performance. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: The framework will remind the team where they are and where they need to focus their effort next.

|

Fundamental Ten:Often the best path to high value performance improvements, especially when you have a limited process improvement budget, is to spend less time collecting data, and more time analyzing what data you have collected, and then using the results of that analysis to keep refining your resolution and measurements to ensure you are moving in the right direction. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: You may decide there are other important things you work with that you want to monitor and progress, beyond the essentials defined within the framework.

Therefore the framework will allow you to add your own important things to monitor and progress.

|

Fundamental Eleven:Just following a process isn’t enough to sustain high performance. It must be the right process that addresses the real goal. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: The framework will not magically give you answers to all your challenges, but it will provide a practical and simple way to rapidly remind people what is most important to be focusing on right now, and it will provide a structure under which you can add more specific information to help you find your own answers to your challenges.

The rationale for this framework need is based on the observation that too often practitioners are faced with too much work on their plate and they often need help in deciding where the priority should be placed.

|

Fundamental Twelve:Even if we know it makes sense to practice, it won’t help if we don’t discipline ourselves to do it consistently at the right time. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: The framework must be easy to access, use and update as practitioners learn new things interacting with their teammates each day on the job.

The rationale for this framework need is based on the observation that if it isn’t easy to access, use and update, it simply won’t be used by busy practitioners.

|

Fundamental Thirteen:Once you have achieved your performance objectives you have to keep making small changes, and you need a mechanism in place to rapidly sense the effects of those small changes, and rapidly respond to those effects to minimize performance impact. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: The framework supports fundamental thirteen by placing practitioners in control of their own practices and giving them a mechanism to keep their practices current with the information they need to continue to maintain high performance.

|

Fundamental Fourteen:The most valuable performance improvements often involve situations that seem to defy resolution because there is no quick fix, but we know they are critical to our performance and we know there is no way to work around them so we must continually deal with them head on. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: The framework will provide reminders to practitioners of common situations they should be alert to, and possible options and consequences to potential related decisions.

|

Fundamental Fifteen:Just knowing what is happening isn’t enough to keep it from happening again. You must practice continually at just the right time with the right objective and contextual data, if you really want to make the changes necessary to sustain higher performance. |

Related Thinking Framework Need: The framework will focus on the most important things we work with. It will help our teams assess their progress in a consistent agreed to way reminding them when they need to rapidly respond with a change.

Neuroscience, Human Decision-Making and the Stories in this Book

Today through recent breakthroughs in neuroscience we understand more clearly how human decision-making occurs [19, 20], and through the stories in this book you will learn how to leverage this new information about decision-making to help the performance of your people and your organization.

This Book is for You if…

You are an organizational leader, process improvement professional or software or systems practitioner and…

- you believe there is no single best approach to performance improvement.5

- you believe the best approach to performance improvement includes conscious thought and clear decision-making integrated into every team and practitioner’s way of working.

- you want to learn why many performance improvement efforts fall short of their goals so you can avoid similar pitfalls.

- you are interested in learning fundamentals that are common to all successful improvement approaches, but are often missed.

- you are ready to do some out-of-the-box thinking related to the performance improvement problem we all face today.

- you are interested in improving both your own personal and your organization’s performance.

- you are interested in seeing practical and easy to understand examples of high maturity thinking (although some may be non-traditional) that can bridge traditional and agile approaches.

- you are interested in learning about proven techniques that can help both your organization’s performance and your practitioner’s performance.

- you believe the best path to high value sustainable performance improvements is incremental, continuous and must involve practitioners in a more active way than what most organizations have done in the past.

About the Terms Process and Practice in This Book

The CMMI defines the term “process” as “a set of interrelated activities which transform inputs into outputs to achieve a given purpose. “ The term process has historically been associated with the written description of the process. Some organizations use the term practices the same way. That is they view their “practices” as a description of how they would like their people to behave. But the practices (or processes) that an organization actually follows may not be written down. They may be tacitly known and followed by the people in the organization. In this book when I use the term “practice” or “process” as a noun I mean it to include both types– written and tacit.

When I use the term practice as a verb, I mean the activity of rehearsing your practices. Do you think you need to rehearse your practices to gain the potential high value payback? Or do you think you just need to be given a little training in your practices before you follow them for real and then you will naturally get better through experience alone?

If you believe that preparing is important before you perform, then how should you go about doing it, when should you do it, and how much of it should you do, if you want to maximize a high value payback for your effort? These are questions that rest at the core of the subject matter in this book.