Chapter 8 – Defining new types with classes

You can get a long way in Python using the built in scalar and collections types. For many problems the built in types, together with those available in the Python Standard Library, are completely sufficient. Sometimes though, they aren’t quite what’s required, and the ability to create custom types is where classes come in.

As we’ve seen, all objects in Python have a type, and when we report that

type using the type() built-in function the result is couched in terms

of the class of that type:

>>> type(5)

<class 'int'>

>>> type("python")

<class 'str'>

>>> type([1, 2, 3])

<class 'list'>

>>> type(x*x for x in [2, 4, 6])

<class 'generator'>

A class is used to define the structure and behaviour of one or more objects,

each of which we refer to as an instance of the class. By and large, objects

in Python have a fixed type2 from the time they are created – or

instantiated – to the time they are destroyed3. It may be

helpful to think of a class as a sort of template or cookie-cutter used to

construct new objects. The class of an object controls its initialization and

which attributes and methods are available through that object. For example, on

a string object the methods we can use on that object, such as split(), are

defined in the str class.

Classes are an important piece of machinery for Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) in Python, and although it’s true that OOP can be useful for making complex problems more tractable, it often has the effect of making the solution to simple problems unnecessarily complex. A great thing about Python is that it’s highly object-oriented without forcing you to deal with classes until you really need them. This sets the language starkly apart from Java and C#.

Defining classes

Class definitions are introduced by the class keyword followed by the class

name. By convention, new class names in Python use camel case – sometimes known

as Pascal case – with an initial capital letter for each and every component

word, without separating underscores. Since classes are a bit awkward to define

at the REPL, we’ll be using a Python module file to hold the class definitions

we use in this chapter.

Let’s start with the very simplest class, to which we’ll progressively

add features. In our example we’ll model a passenger aircraft flight between two

airports by putting this code into airtravel.py:

"""Model for aircraft flights."""

class Flight:

pass

The class statement introduces a new block, so we indent on the next

line. Empty blocks aren’t allowed, so the simplest possible class needs

at least a do-nothing pass statement to be syntactically admissible.

Just as with def for defining functions, class is a statement that

can occur anywhere in a program and which binds a class definition to a

class name. When the top-level code in the airtravel module is

executed, the class will be defined.

We can now import our new class into the REPL and try it out.

>>> from airtravel import Flight

The thing we’ve just imported is the class object. Everything is an object in Python, and classes are no exception.

>>> Flight

<class 'airtravel.Flight'>

To use this class to mint a new object, we must call its constructor, which is

done by calling the class, as we would a function. The constructor

returns a new object, which here we assign to a name f:

>>> f = Flight()

If we use the type() function to request the type of f, we get

airtravel.Flight:

>>> type(f)

<class 'airtravel.Flight'>

The type of f literally is the class.

Instance methods

Let’s make our class a little more interesting, by adding a so-called instance

method which returns the flight number. Methods are just functions defined

within the class block, and instance methods are functions which can be called

on objects which are instances of our class, such as f. Instance methods must

accept a reference to the instance on which the method was called as the first

formal argument4, and by convention this argument is always called

self.

We have no way of configuring the flight number value yet, so we’ll just return a constant string:

class Flight:

def number(self):

return "SN060"

and from a fresh REPL:

>>> from airtravel import Flight

>>> f = Flight()

>>> f.number()

SN060

Notice that when we call the method, we do not provide the instance f

for the actual argument5 self in the argument list. That’s because the

standard method invocation form:

>>> f.number()

SN060

is syntactic sugar for:

>>> Flight.number(f)

SN060

If you try the latter, you’ll find that it works as expected, although you’ll almost never see this form used for real.

Instance initializers

This class isn’t very useful, because it can only represent one

particular flight. We need to make the flight number configurable at the

point a Flight is created. To do that we need to write an initializer method.

If provided, the initializer method is called as part of the process

of creating a new object when we call the constructor. The initializer

method must be called __init__() delimited by the double underscores

used for Python runtime machinery. Like all other instance methods, the

first argument to __init__() must be self.

In this case, we also pass a second formal argument to __init__() which is

the flight number:

class Flight:

def __init__(self, number):

self._number = number

def number(self):

return self._number

The initializer should not return anything – it modifies the

object referred to by self.

If you’re coming from a Java, C#, or C++ background it’s tempting to

think of __init__() as being the constructor. This isn’t quite

accurate; in Python the purpose of __init__() is to configure an

object that already exists by the time __init__() is called. The

self argument is, however, analogous to this in Java, C#, or C++. In

Python the actual constructor is provided by the Python runtime system

and one of the things it does is check for the existence of an instance

initializer and call it when present.

Within the initializer we assign to an attribute of the newly created

instance called _number. Assigning to an object attribute that

doesn’t yet exist is sufficient to bring it into existence.

Just as we don’t need to declare variables until we create them, neither do we

need to declare object attributes before we create them. We choose _number

with a leading underscore for two reasons. First, because it avoids a name clash

with the method of the same name. Methods are functions, functions are objects,

and these functions are bound to attributes of the object, so we already have an

attribute called number and we don’t want to replace it. Second, there is a

widely followed convention that the implementation details of objects which are

not intended for consumption or manipulation by clients of the object should be

prefixed with an underscore.

We also modify our number() method to access the _number attribute

and return it.

Any actual arguments passed to the flight constructor will be forwarded to the

initializer, so to create and configure our Flight object we can now

do this:

>>> from airtravel import Flight

>>> f = Flight("SN060")

>>> f.number()

SN060

We can also directly access the implementation details:

>>> f._number

SN060

Although this is not recommended for production code, it’s very handy for debugging and early testing.

A lack of access modifiers

If you’re coming from a bondage and discipline language like Java or C#

with public, private and protected access modifiers, Python’s

“everything is public” approach can seem excessively open-minded.

The prevailing culture among Pythonistas is that “We’re all consenting adults here”. In practice, the leading underscore convention has proven sufficient protection even in large and complex Python systems we have worked with. People know not to use these attributes directly, and in fact they tend not to. Like so many doctrines, lack of access modifiers is a much bigger problem in theory than in practice.

Validation and invariants

It’s good practice for the initializer of an object to establish so-called class invariants. The invariants are truths about objects of that class that should endure for the lifetime of the object. One such invariant for flights is that the flight number always begins with an upper case two-letter airline code followed by a three or four digit route number.

In Python, we establish class invariants in the __init__() method and

raise exceptions if they can’t be attained:

class Flight:

def __init__(self, number):

if not number[:2].isalpha():

raise ValueError("No airline code in '{}'".format(number))

if not number[:2].isupper():

raise ValueError("Invalid airline code '{}'".format(number))

if not (number[2:].isdigit() and int(number[2:]) <= 9999):

raise ValueError("Invalid route number '{}'".format(number))

self._number = number

def number(self):

return self._number

We use string slicing and various methods of the string class to perform

validation. For the first time in this book we also see the logical

negation operator not.

Ad hoc testing in the REPL is a very effective technique during development:

>>> from airtravel import Flight

>>> f = Flight("SN060")

>>> f = Flight("060")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "./airtravel.py", line 8, in __init__

raise ValueError("No airline code in '{};".format(number))

ValueError: No airline code in '060'

>>> f = Flight("sn060")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "./airtravel.py", line 11, in __init__

raise ValueError("Invalid airline code '{}'".format(number))

ValueError: Invalid airline code 'sn060'

>>> f = Flight("snabcd")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "./airtravel.py", line 11, in __init__

raise ValueError("Invalid airline code '{}'".format(number))

ValueError: Invalid airline code 'snabcd'

>>> f = Flight("SN12345")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "./airtravel.py", line 14, in __init__

raise ValueError("Invalid route number '{}'".format(number))

ValueError: Invalid route number 'SN12345'

Now that we’re sure of having a valid flight number, we’ll add a second method to return just the airline code. Once the class invariants have been established, most query methods can be very simple:

def airline(self):

return self._number[:2]

Adding a second class

One of the things we’d like to do with our flight is accept seat bookings. To do that we need to know the seating layout, and for that we need to know the type of aircraft. Let’s make a second class to model different kinds of aircraft:

class Aircraft:

def __init__(self, registration, model, num_rows, num_seats_per_row):

self._registration = registration

self._model = model

self._num_rows = num_rows

self._num_seats_per_row = num_seats_per_row

def registration(self):

return self._registration

def model(self):

return self._model

The initializer creates four attributes for the aircraft: registration number, a model name, the number of rows of seats, and the number of seats per row. In a production code scenario we could validate these arguments to ensure, for example, that the number of rows is not negative.

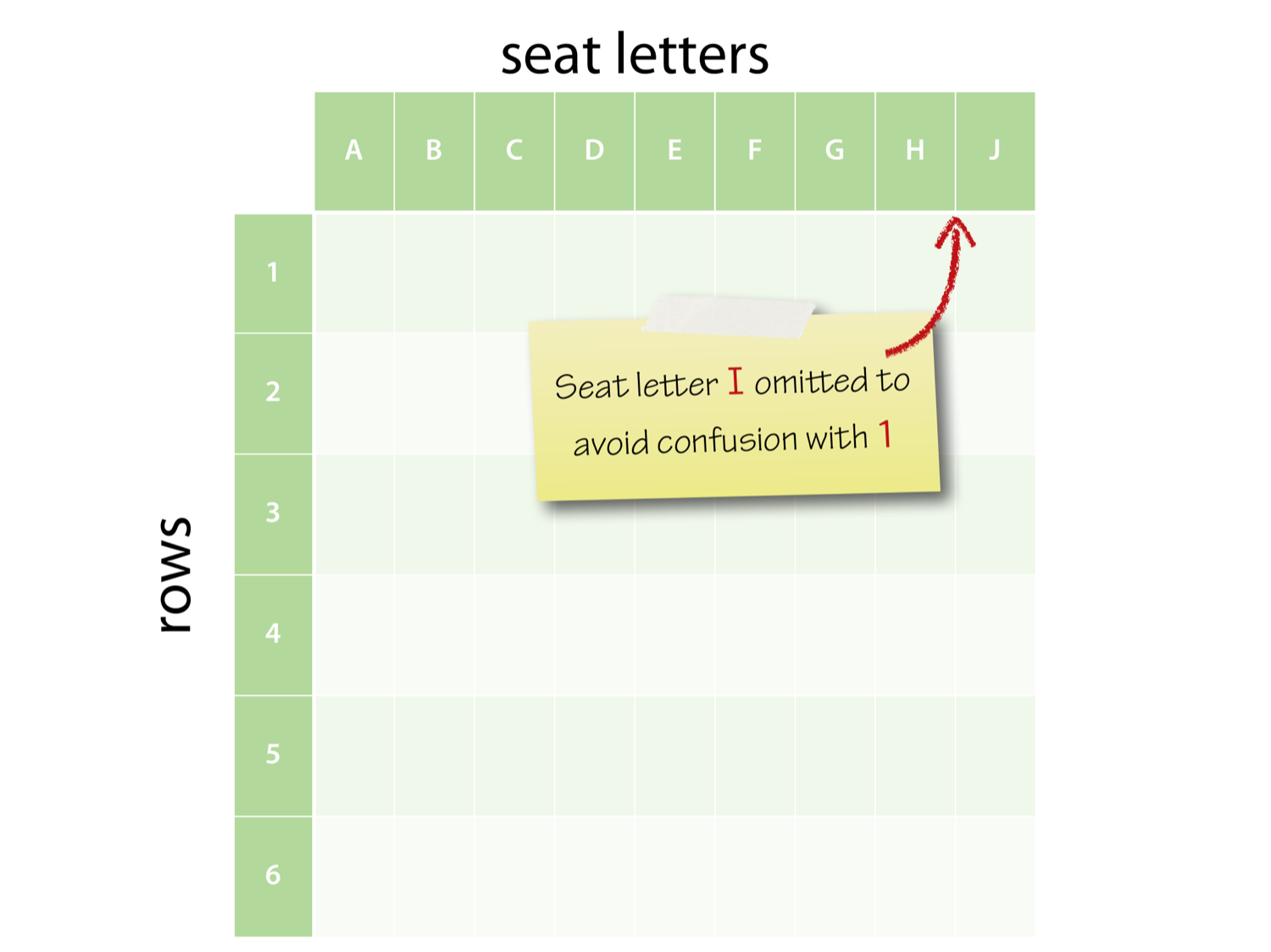

This is straightforward enough, but for the seating plan we’d like something a little more in line with our booking system. Rows in aircraft are numbered from one, and the seats within each row are designated with letters from an alphabet which omits ‘I’ to avoid confusion with ‘1’.

We’ll add a seating_plan() method which returns the allowed rows and

seats as a 2-tuple containing a range object and a string of seat letters:

def seating_plan(self):

return (range(1, self._num_rows + 1),

"ABCDEFGHJK"[:self._num_seats_per_row])

It’s worth pausing for a second to make sure you understand how this function

works. The call to the range() constructor produces a range object which can

be used as an iterable series of row numbers, up to the number of rows in the

plane. The string and its slice method return a string with one character per

seat. These two objects – the range and the string – are bundled up into a

tuple.

Let’s construct a plane with a seating plan:

>>> from airtravel import *

>>> a = Aircraft("G-EUPT", "Airbus A319", num_rows=22, num_seats_per_row=6)

>>> a.registration()

'G-EUPT'

>>> a.model()

'Airbus A319'

>>> a.seating_plan()

(range(1, 23), 'ABCDEF')

See how we used keyword arguments for the rows and seats for documentary purposes. Recall the ranges are half-open, so 23 is correctly one-beyond-the-end of the range.

Collaborating classes

The Law of Demeter is an object-oriented design principle that says you should never call methods on objects you receive from other calls. Or, put another way: Only talk to your immediate friends.

We’ll now modify our Flight class to accept an aircraft object when it

is constructed, and we’ll follow the Law of Demeter by adding a method

to report the aircraft model. This method will delegate to Aircraft on

behalf of the client rather than allowing the client to “reach through”

the Flight and interrogate the Aircraft object directly:

class Flight:

"""A flight with a particular passenger aircraft."""

def __init__(self, number, aircraft):

if not number[:2].isalpha():

raise ValueError("No airline code in '{}'".format(number))

if not number[:2].isupper():

raise ValueError("Invalid airline code '{}'".format(number))

if not (number[2:].isdigit() and int(number[2:]) <= 9999):

raise ValueError("Invalid route number '{}'".format(number))

self._number = number

self._aircraft = aircraft

def number(self):

return self._number

def airline(self):

return self._number[:2]

def aircraft_model(self):

return self._aircraft.model()

We’ve also added a docstring to the class. These work just like function and module docstrings, and must be the first non-comment line within the body of the class.

We can now construct a flight with a specific aircraft:

>>> from airtravel import *

>>> f = Flight("BA758", Aircraft("G-EUPT", "Airbus A319", num_rows=22,

... num_seats_per_row=6))

>>> f.aircraft_model()

'Airbus A319'

Notice that we construct the Aircraft object and directly pass it to

the Flight constructor without needing an intermediate named reference

for it.

Moment of zen

The aircraft_model() method is an example of ‘complex is better than

complicated’:

def aircraft_model(self):

return self._aircraft.model()

The Flight class is more complex – it contains additional code to

drill down through the aircraft reference to find the model. However,

all clients of Flight can now be less complicated; none of them need

to know about the Aircraft class, dramatically simplifying the system.

Booking seats

Now we can proceed with implementing a simple booking system. For each

flight we need to keep track of who is sitting in each seat.

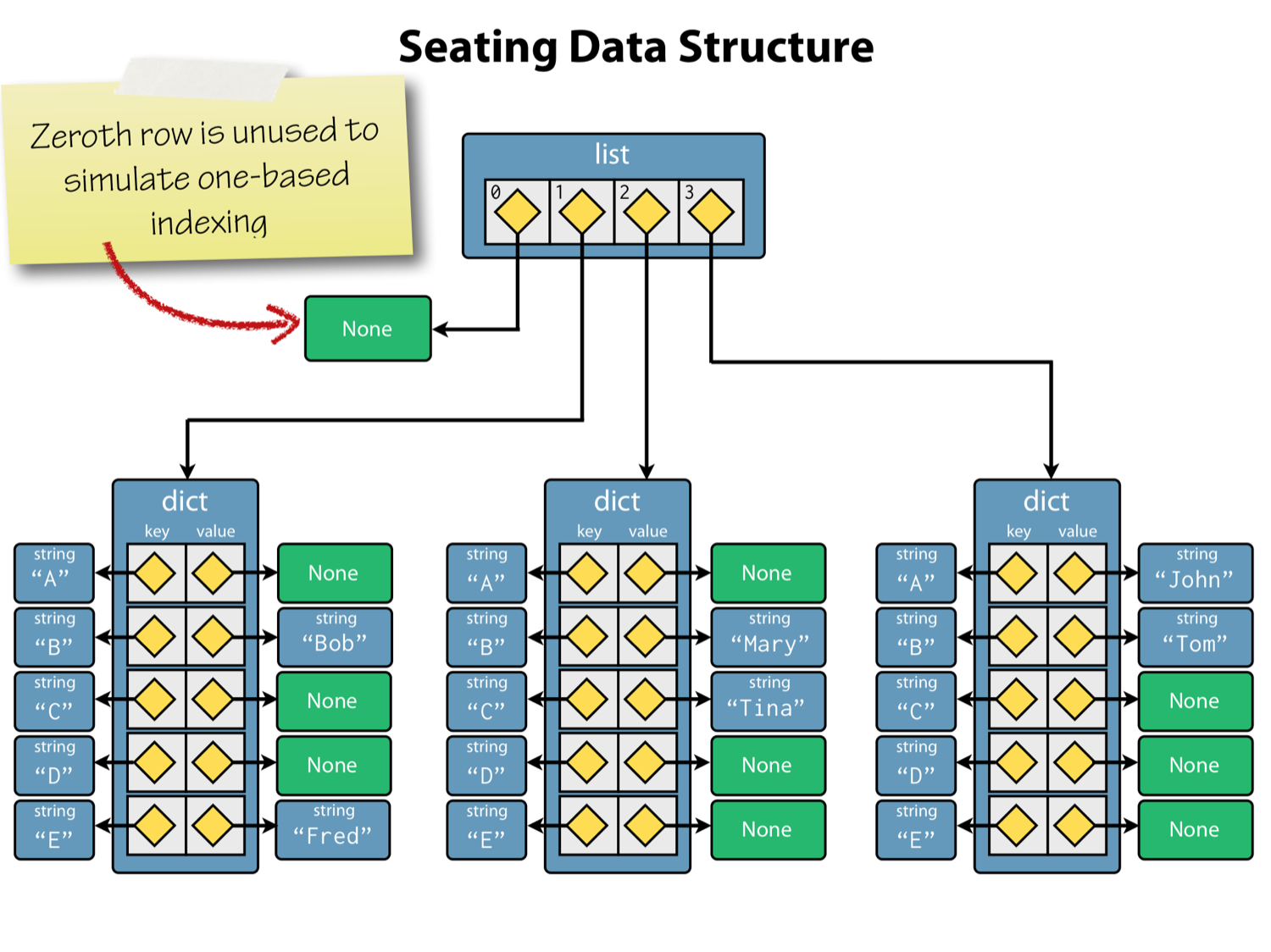

We’ll represent the seat allocations using a list of dictionaries. The

list will contain one entry for each seat row, and each entry will be a

dictionary mapping from seat-letter to occupant name. If a seat is unoccupied,

the corresponding dictionary value will contain None.

We initialize the seating plan in Flight.__init__() using this

fragment:

rows, seats = self._aircraft.seating_plan()

self._seating = [None] + [{letter: None for letter in seats} for _ in rows]

In the first line we retrieve the seating plan for the aircraft and use tuple

unpacking to put the row and seat identifiers into local variables rows and

seats. In the second line we create a list for the seat allocations. Rather

than continually deal with the fact that row indexes are one-based whereas

Python lists use zero-based indexes, we choose to waste one entry at the

beginning of the list. This first wasted entry is the single element list

containing None. To this single element list we concatenate another list

containing one entry for each real row in the aircraft. This list is constructed

by a list comprehension which iterates over the rows object, which is the

range of row numbers retrieved from the _aircraft on the previous line.

We’re not actually interested in the row number, since we know it will match up with the list index in the final list, so we discard it by using the dummy underscore variable.

The item expression part of the list comprehension is itself a

comprehension; specifically a dictionary comprehension! This iterates

over each row letter, and creates a mapping from the single

character string to None to indicate an empty seat.

We use a list comprehension, rather than list replication with the multiplication operator, because we want a distinct dictionary object to be created for each row; remember, repetition is shallow.

Here’s the code after we put it into the initializer:

def __init__(self, number, aircraft):

if not number[:2].isalpha():

raise ValueError("No airline code in '{}'".format(number))

if not number[:2].isupper():

raise ValueError("Invalid airline code '{}'".format(number))

if not (number[2:].isdigit() and int(number[2:]) <= 9999):

raise ValueError("Invalid route number '{}'".format(number))

self._number = number

self._aircraft = aircraft

rows, seats = self._aircraft.seating_plan()

self._seating = [None] + [{letter: None for letter in seats} for _ in rows]

Before we go further, let’s test our code in the REPL:

>>> from airtravel import *

>>> f = Flight("BA758", Aircraft("G-EUPT", "Airbus A319", num_rows=22,

... num_seats_per_row=6))

>>>

Thanks to the fact that everything is “public” we can access implementation details during development. It’s clear enough that we’re deliberately defying convention here during development, since the leading underscore reminds us what’s “public” and what’s “private”:

>>> f._seating

[None, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None},

{'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None,

'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None,

'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None,

'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None,

'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None,

'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None},

{'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None,

'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None,

'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None,

'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None,

'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None,

'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None},

{'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None,

'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None,

'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None,

'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None,

'C': None, 'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None,

'A': None}, {'F': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'A': None}]

That’s accurate, but not particularly beautiful. Let’s try again with pretty-print:

>>> from pprint import pprint as pp

>>> pp(f._seating)

[None,

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None}]

Perfect!

Allocating seats to passengers

Now we’ll add behavior to Flight to allocate seats to passengers. To

keep this simple, a passenger will be a string name:

1 class Flight:

2

3 # ...

4

5 def allocate_seat(seat, passenger):

6 """Allocate a seat to a passenger.

7

8 Args:

9 seat: A seat designator such as '12C' or '21F'.

10 passenger: The passenger name.

11

12 Raises:

13 ValueError: If the seat is unavailable.

14 """

15 rows, seat_letters = self._aircraft.seating_plan()

16

17 letter = seat[-1]

18 if letter not in seat_letters:

19 raise ValueError("Invalid seat letter {}".format(letter))

20

21 row_text = seat[:-1]

22 try:

23 row = int(row_text)

24 except ValueError:

25 raise ValueError("Invalid seat row {}".format(row_text))

26

27 if row not in rows:

28 raise ValueError("Invalid row number {}".format(row))

29

30 if self._seating[row][letter] is not None:

31 raise ValueError("Seat {} already occupied".format(seat))

32

33 self._seating[row][letter] = passenger

Most of this code is validation of the seat designator and it contains some interesting snippets:

- Line 6: Methods are functions, so deserve docstrings too.

- Line 17: We get the seat letter by using negative indexing into the

seatstring. - Line 18: We test that the seat letter is valid by checking for membership

of

seat_lettersusing theinmembership testing operator. - Line 21: We extract the row number using string slicing to take all but the last character.

- Line 23: We try to convert the row number substring to an integer using the

int()constructor. If this fails, we catch theValueErrorand in the handler raise a newValueErrorwith a more appropriate message payload. - Line 27: We conveniently validate the row number by using the

inoperator against therowsobject which is arange. We can do this becauserange()objects support the container protocol. - Line 30: We check that the requested seat is unoccupied using an identity

test with

None. If it’s occupied we raise aValueError. - Line 33: If we get this far, everything is is good shape, and we can assign the seat.

This code also contains a bug, which we’ll discover soon enough!

Trying our seat allocator at the REPL:

>>> from airtravel import *

>>> f = Flight("BA758", Aircraft("G-EUPT", "Airbus A319",

... num_rows=22, num_seats_per_row=6))

>>> f.allocate_seat('12A', 'Guido van Rossum')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: allocate_seat() takes 2 positional arguments but 3 were given

Oh dear! Early on in your object-oriented Python career you’re likely to see

TypeError messages like this quite often. The problem has occurred because we

forgot to include the self argument in the definition of the allocate_seat()

method:

def allocate_seat(self, seat, passenger):

# ...

Once we fix that, we can try again:

>>> from airtravel import *

>>> from pprint import pprint as pp

>>> f = Flight("BA758", Aircraft("G-EUPT", "Airbus A319",

... num_rows=22, num_seats_per_row=6))

>>> f.allocate_seat('12A', 'Guido van Rossum')

>>> f.allocate_seat('12A', 'Rasmus Lerdorf')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "./airtravel.py", line 57, in allocate_seat

raise ValueError("Seat {} already occupied".format(seat))

ValueError: Seat 12A already occupied

>>> f.allocate_seat('15F', 'Bjarne Stroustrup')

>>> f.allocate_seat('15E', 'Anders Hejlsberg')

>>> f.allocate_seat('E27', 'Yukihiro Matsumoto')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "./airtravel.py", line 45, in allocate_seat

raise ValueError("Invalid seat letter {}".format(letter))

ValueError: Invalid seat letter 7

>>> f.allocate_seat('1C', 'John McCarthy')

>>> f.allocate_seat('1D', 'Richard Hickey')

>>> f.allocate_seat('DD', 'Larry Wall')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "./airtravel.py", line 49, in allocate_seat

row = int(row_text)

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'D'

During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "./airtravel.py", line 51, in allocate_seat

raise ValueError("Invalid seat row {}".format(row_text))

ValueError: Invalid seat row D

>>> pp(f._seating)

[None,

{'A': None,

'B': None,

'C': 'John McCarthy',

'D': 'Richard Hickey',

'E': None,

'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': 'Guido van Rossum',

'B': None,

'C': None,

'D': None,

'E': None,

'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None,

'B': None,

'C': None,

'D': None,

'E': 'Anders Hejlsberg',

'F': 'Bjarne Stroustrup'},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None}]

The Dutchman is quite lonely there in row 12, so we’d like to move him

back to row 15 with the Danes. To do so, we’ll need a

relocate_passenger() method.

Naming methods for implementation details

First we’ll perform a small refactoring and extract the seat designator

parsing and validation logic into its own method, _parse_seat(). We

use a leading underscore here because this method is an implementation

detail:

class Flight:

# ...

def _parse_seat(self, seat):

"""Parse a seat designator into a valid row and letter.

Args:

seat: A seat designator such as 12F

Returns:

A tuple containing an integer and a string for row and seat.

"""

row_numbers, seat_letters = self._aircraft.seating_plan()

letter = seat[-1]

if letter not in seat_letters:

raise ValueError("Invalid seat letter {}".format(letter))

row_text = seat[:-1]

try:

row = int(row_text)

except ValueError:

raise ValueError("Invalid seat row {}".format(row_text))

if row not in row_numbers:

raise ValueError("Invalid row number {}".format(row))

return row, letter

The new _parse_seat() method returns a tuple with an integer row

number and a seat letter string. This has made allocate_seat() much

simpler:

def allocate_seat(self, seat, passenger):

"""Allocate a seat to a passenger.

Args:

seat: A seat designator such as '12C' or '21F'.

passenger: The passenger name.

Raises:

ValueError: If the seat is unavailable.

"""

row, letter = self._parse_seat(seat)

if self._seating[row][letter] is not None:

raise ValueError("Seat {} already occupied".format(seat))

self._seating[row][letter] = passenger

Notice how the call to _parse_seat() also requires explicit qualification with

the self prefix.

Implementing relocate_passenger()

Now we’ve laid the groundwork for our relocate_passenger() method:

class Flight:

# ...

def relocate_passenger(self, from_seat, to_seat):

"""Relocate a passenger to a different seat.

Args:

from_seat: The existing seat designator for the

passenger to be moved.

to_seat: The new seat designator.

"""

from_row, from_letter = self._parse_seat(from_seat)

if self._seating[from_row][from_letter] is None:

raise ValueError("No passenger to relocate in seat {}".format(from_seat))

to_row, to_letter = self._parse_seat(to_seat)

if self._seating[to_row][to_letter] is not None:

raise ValueError("Seat {} already occupied".format(to_seat))

self._seating[to_row][to_letter] = self._seating[from_row][from_letter]

self._seating[from_row][from_letter] = None

This parses and validates the from_seat and to_seat arguments and

then moves the passenger to the new location.

It’s also getting tiresome recreating the Flight object each time, so

we’ll add a module level convenience function for that too:

def make_flight():

f = Flight("BA758", Aircraft("G-EUPT", "Airbus A319",

num_rows=22, num_seats_per_row=6))

f.allocate_seat('12A', 'Guido van Rossum')

f.allocate_seat('15F', 'Bjarne Stroustrup')

f.allocate_seat('15E', 'Anders Hejlsberg')

f.allocate_seat('1C', 'John McCarthy')

f.allocate_seat('1D', 'Richard Hickey')

return f

In Python it’s quite normal to mix related functions and classes in the same module. Now, from the REPL:

>>> from airtravel import make_flight

>>> f = make_flight()

>>> f

<airtravel.Flight object at 0x1007a6690>

You may find it remarkable that we have access to the Flight class

when we have only imported a single function, make_flight. This is quite

normal and it’s a powerful aspect of Python’s dynamic type system that

facilitates this very loose coupling between code.

Let’s get on and move Guido back to row 15 with his fellow Europeans:

>>> f.relocate_passenger('12A', '15D')

>>> from pprint import pprint as pp

>>> pp(f._seating)

[None,

{'A': None,

'B': None,

'C': 'John McCarthy',

'D': 'Richard Hickey',

'E': None,

'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None,

'B': None,

'C': None,

'D': 'Guido van Rossum',

'E': 'Anders Hejlsberg',

'F': 'Bjarne Stroustrup'},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None},

{'A': None, 'B': None, 'C': None, 'D': None, 'E': None, 'F': None}]

Counting available seats

It’s important during booking to know how many seats are available. To this end

we’ll write a num_available_seats() method. This uses two nested generator

expressions. The outer expression filters for all rows which are not None to

exclude our dummy first row. The value of each item in the outer

expression is the sum of the number of None values in each row. This inner

expression iterates over values of the dictionary and adds 1 for each None

found:

def num_available_seats(self):

return sum( sum(1 for s in row.values() if s is None)

for row in self._seating

if row is not None )

Notice how we have split the outer expression over three lines to improve readability.

>>> from airtravel import make_flight

>>> f = make_flight()

>>> f.num_available_seats()

127

A quick check shows that our new calculation is correct:

>>> 6 * 22 - 5

127

Sometimes the only object you need is a function

Now we’ll show how it’s quite possible to write nice object-oriented

code without needing classes. We have a requirement to produce boarding

cards for our passengers in alphabetical order. However, we realize that

the flight class is probably not a good home for details of printing

boarding passes. We could go ahead and create a BoardingCardPrinter

class, although that is probably overkill. Remember that functions are

objects too and are perfectly sufficient for many cases. Don’t feel

compelled to make classes without good reason.

Rather than have a card printer query all the passenger details from the

flight, we’ll follow the object-oriented design principle of “Tell!

Don’t Ask.” and have the Flight tell a simple card printing function

what to do.

First the card printer, which is just a module level function:

def console_card_printer(passenger, seat, flight_number, aircraft):

output = "| Name: {0}" \

" Flight: {1}" \

" Seat: {2}" \

" Aircraft: {3}" \

" |".format(passenger, flight_number, seat, aircraft)

banner = '+' + '-' * (len(output) - 2) + '+'

border = '|' + ' ' * (len(output) - 2) + '|'

lines = [banner, border, output, border, banner]

card = '\n'.join(lines)

print(card)

print()

A Python feature we’re introducing here is the use of line continuation backslash characters, ‘\’, which allow us to split long statements over several lines. This is used here, together with implicit string concatenation of adjacent strings, to produce one long string with no line breaks.

We measure the length of this output line, build some banners and borders

around it and, concatenate the lines together using the join() method

called on a newline separator. The whole card is then printed, followed by a

blank line. The card printer doesn’t know anything about Flights or Aircraft –

it’s very loosely coupled. You can probably easily envisage an HTML card printer

that has the same interface.

Making Flight create boarding cards

To the Flight class we add a new method make_boarding_cards() which

accepts a card_printer:

class Flight:

# ...

def make_boarding_cards(self, card_printer):

for passenger, seat in sorted(self._passenger_seats()):

card_printer(passenger, seat, self.number(), self.aircraft_model())

This tells the card_printer to print each passenger, having sorted a list of

passenger-seat tuples obtained from a _passenger_seats() implementation detail

method (note the leading underscore). This method is in fact a generator function

which searches all seats for occupants, yielding the passenger and the seat

number as they are found:

def _passenger_seats(self):

"""An iterable series of passenger seating allocations."""

row_numbers, seat_letters = self._aircraft.seating_plan()

for row in row_numbers:

for letter in seat_letters:

passenger = self._seating[row][letter]

if passenger is not None:

yield (passenger, "{}{}".format(row, letter))

Now if we run this on the REPL, we can see that the new boarding card printing system works:

>>> from airtravel import console_card_printer, make_flight

>>> f = make_flight()

>>> f.make_boarding_cards(console_card_printer)

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Name: Anders Hejlsberg Flight: BA758 Seat: 15E Aircraft: Airbus A319 |

| |

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

+--------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Name: Bjarne Stroustrup Flight: BA758 Seat: 15F Aircraft: Airbus A319 |

| |

+--------------------------------------------------------------------------+

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Name: Guido van Rossum Flight: BA758 Seat: 12A Aircraft: Airbus A319 |

| |

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

+---------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Name: John McCarthy Flight: BA758 Seat: 1C Aircraft: Airbus A319 |

| |

+---------------------------------------------------------------------+

+----------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Name: Richard Hickey Flight: BA758 Seat: 1D Aircraft: Airbus A319 |

| |

+----------------------------------------------------------------------+

Polymorphism and duck-typing

Polymorphism is a programming language feature which allows us to use objects of

different types through a uniform interface. The concept of polymorphism applies

to both functions and more complex objects. We’ve just seen an example of

polymorphism with the card printing example. The make_boarding_card() method

didn’t need to know about an actual – or as we say “concrete” – card printing

type, only the abstract details of its interface. This interface is essentially

just the order of its arguments. Replacing our console_card_printer with a

putative html_card_printer would exercise polymorphism.

Polymorphism in Python is achieved through duck typing. Duck typing is in turn named after the “duck test”, attributed to James Whitcomb Riley, the American poet.

When I see a bird that walks like a duck and swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck.

Duck typing, where an object’s fitness for a particular use is only determined at runtime, is the cornerstone of Python’s object system. This is different from many statically typed languages where a compiler determines if an object can be used. In particular, it means that an object’s suitability is not based on inheritance hierarchies, base classes, or anything except the attributes an object has at the time of use.

This is in stark contrast to languages such as Java which depend on what is called nominal sub-typing through inheritance from base classes and interfaces. We’ll talk more about inheritance in the context of Python shortly.

Refactoring Aircraft

Let’s return to our Aircraft class:

class Aircraft:

def __init__(self, registration, model, num_rows, num_seats_per_row):

self._registration = registration

self._model = model

self._num_rows = num_rows

self._num_seats_per_row = num_seats_per_row

def registration(self):

return self._registration

def model(self):

return self._model

def seating_plan(self):

return (range(1, self._num_rows + 1),

"ABCDEFGHJK"[:self._num_seats_per_row])

The design of this class is somewhat flawed because users who instantiate it have to supply a seating configuration that matches the aircraft model. For the purposes of this exercise we can assume that the seating arrangement is fixed per aircraft model.

Better, and simpler, perhaps to get rid of the Aircraft class entirely

and make separate classes for each specific model of aircraft with a

fixed seating configuration. Here’s an Airbus A319:

class AirbusA319:

def __init__(self, registration):

self._registration = registration

def registration(self):

return self._registration

def model(self):

return "Airbus A319"

def seating_plan(self):

return range(1, 23), "ABCDEF"

And here’s a Boeing 777:

class Boeing777:

def __init__(self, registration):

self._registration = registration

def registration(self):

return self._registration

def model(self):

return "Boeing 777"

def seating_plan(self):

# For simplicity's sake, we ignore complex

# seating arrangement for first-class

return range(1, 56), "ABCDEGHJK"

These two aircraft classes have no explicit relationship to each other, or to

our original Aircraft class, beyond having identical interfaces (with the

exception of the initializer, which now takes fewer arguments). As such we can

use these new types in place of each other.

Let’s change our make_flight() method to make_flights() so we can use

them:

def make_flights():

f = Flight("BA758", AirbusA319("G-EUPT"))

f.allocate_seat('12A', 'Guido van Rossum')

f.allocate_seat('15F', 'Bjarne Stroustrup')

f.allocate_seat('15E', 'Anders Hejlsberg')

f.allocate_seat('1C', 'John McCarthy')

f.allocate_seat('1D', 'Richard Hickey')

g = Flight("AF72", Boeing777("F-GSPS"))

g.allocate_seat('55K', 'Larry Wall')

g.allocate_seat('33G', 'Yukihiro Matsumoto')

g.allocate_seat('4B', 'Brian Kernighan')

g.allocate_seat('4A', 'Dennis Ritchie')

return f, g

The different types of aircraft both work fine when used with Flight

because they both quack like ducks. Or fly like planes. Or something:

>>> from airtravel import *

>>> f, g = make_flights()

>>> f.aircraft_model()

'Airbus A319'

>>> g.aircraft_model()

'Boeing 777'

>>> f.num_available_seats()

127

>>> g.num_available_seats()

491

>>> g.relocate_passenger('55K', '13G')

>>> g.make_boarding_cards(console_card_printer)

+---------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Name: Brian Kernighan Flight: AF72 Seat: 4B Aircraft: Boeing 777 |

| |

+---------------------------------------------------------------------+

+--------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Name: Dennis Ritchie Flight: AF72 Seat: 4A Aircraft: Boeing 777 |

| |

+--------------------------------------------------------------------+

+-----------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Name: Larry Wall Flight: AF72 Seat: 13G Aircraft: Boeing 777 |

| |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------+

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| |

| Name: Yukihiro Matsumoto Flight: AF72 Seat: 33G Aircraft: Boeing 777 |

| |

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

Duck typing and polymorphism is very important in Python. In fact it’s the basis for the collection protocols we discussed such as iterator, iterable and sequence.

Inheritance and implementation sharing

Inheritance is a mechanism whereby one class can be derived from a base-class allowing us to make behavior more specific in the subclass. In nominally typed languages such as Java, class-based inheritance is the means by which run-time polymorphism is achieved. Not so in Python, as we have just demonstrated. The fact that no Python method calls or attribute lookups are bound to actual objects until the point at which they are called – known as late-binding – means we can attempt polymorphism with any object and it will succeed if the object fits.

Although inheritance in Python can be used to facilitate polymorphism – after all, derived classes will have the same interfaces as base classes – inheritance in Python is most useful for sharing implementation between classes.

A base class for aircraft

As usual, this will make much more sense with an example. We would like

our aircraft classes AirbusA319 and Boeing777 to provide a way of

returning the total number of seats. We’ll add a method called

num_seats() to both classes to do this:

def num_seats(self):

rows, row_seats = self.seating_plan()

return len(rows) * len(row_seats)

The implementation can be identical in both classes, since it can be calculated from the seating plan.

Unfortunately, we now have duplicate code across two classes, and as we add more aircraft types the code duplication will worsen.

The solution is to extract the common elements of AirbusA319 and Boeing777

into a base class from which both aircraft types will derive. Let’s recreate the

class Aircraft, this time with the goal of using it as a base class:

class Aircraft:

def num_seats(self):

rows, row_seats = self.seating_plan()

return len(rows) * len(row_seats)

The Aircraft class contains just the method we want to inherit into the

derived classes. This class isn’t usable on its own because it depends on a

method called seating_plan() which isn’t available at this level. Any attempt

to use it standalone will fail:

>>> from airtravel import *

>>> base = Aircraft()

>>> base.num_seats()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "./airtravel.py", line 125, in num_seats

rows, row_seats = self.seating_plan()

AttributeError: 'Aircraft' object has no attribute 'seating_plan'

The class is abstract insofar as it is never useful to instantiate it alone.

Inheriting from Aircraft

Now for the derived classes. We specify inheritance in Python using

parentheses containing the base class name immediately after the class

name in the class statement.

Here’s the Airbus class:

class AirbusA319(Aircraft):

def __init__(self, registration):

self._registration = registration

def registration(self):

return self._registration

def model(self):

return "Airbus A319"

def seating_plan(self):

return range(1, 23), "ABCDEF"

And this is the Boeing class:

class Boeing777(Aircraft):

def __init__(self, registration):

self._registration = registration

def registration(self):

return self._registration

def model(self):

return "Boeing 777"

def seating_plan(self):

# For simplicity's sake, we ignore complex

# seating arrangement for first-class

return range(1, 56), "ABCDEGHJK"

Let’s exercise them at the REPL:

>>> from airtravel import *

>>> a = AirbusA319("G-EZBT")

>>> a.num_seats()

132

>>> b = Boeing777("N717AN")

>>> b.num_seats()

495

We can see that both subtype aircraft inherited the num_seats method(),

which now works as expected because the call to seating_plan() is

successfully resolved on the self object at runtime.

Hoisting common functionality into a base class

Now we have the base Aircraft class we can refactor by hoisting into it other

common functionality. For example, both the initializer and registration()

methods are identical between the two subtypes:

class Aircraft:

def __init__(self, registration):

self._registration = registration

def registration(self):

return self._registration

def num_seats(self):

rows, row_seats = self.seating_plan()

return len(rows) * len(row_seats)

class AirbusA319(Aircraft):

def model(self):

return "Airbus A319"

def seating_plan(self):

return range(1, 23), "ABCDEF"

class Boeing777(Aircraft):

def model(self):

return "Boeing 777"

def seating_plan(self):

# For simplicities sake, we ignore complex

# seating arrangement for first-class

return range(1, 56), "ABCDEGHJK"

These derived classes only contain the specifics for that aircraft type. All general functionality is shared from the base class by inheritance.

Thanks to duck-typing, inheritance is less used on Python than in other languages. This is generally seen as a good thing because inheritance is a very tight coupling between classes.

Summary

- All types in Python have a ‘class’.

- Classes define the structure and behavior of an object.

- The class of an object is determined when the object is created and is almost always fixed for the lifetime of the object.

- Classes are the key support for Object-Oriented Programming in Python.

- Classes are defined using the

classkeyword followed by the class name, which is in CamelCase. - Instances of a class are created by calling the class as if it were a function.

- Instance methods are functions defined inside the class which should

accept an object instance called

selfas the first parameter. - Methods are called using the

instance.method()syntax which is syntactic sugar for passing the instance as the formalselfargument to the method. - An optional special initializer method called

__init__()can be provided which is used to configure theselfobject at creation time. - The constructor calls the

__init__()method if one is present. - The

__init__()method is not the constructor. The object has been already constructed by the time the initializer is called. The initializer configures the newly created object before it’s returned to the caller of the constructor. - Arguments passed to the constructor are forwarded to the initializer.

- Instance attributes are brought into existence by assigning to them.

- Attributes and methods which are implementation details are by convention prefixed with an underscore. There are no public, protected or private access modifiers in Python.

- Access to implementation details from outside the class can be very useful during development, testing and debugging.

- Class invariants should be established in the initializer. If the invariants can’t be established raise exceptions to signal failure.

- Methods can have docstrings, just like regular functions.

- Classes can have docstrings.

- Even within an object method calls must be qualified with

self. - You can have as many classes and functions in a module as you wish. Related classes and global functions are usually grouped together this way.

- Polymorphism in Python is achieved through duck typing where attributes and methods are only resolved at point of use - a behaviour called late-binding.

- Polymorphism in Python does not require shared base classes or named interfaces.

- Class inheritance in Python is primarily useful for sharing implementation rather than being necessary for polymorphism.

- All methods are inherited, including special methods like the initialiser.

Along the way we found that:

- Strings support slicing, because they implement the sequence protocol.

- Following the Law of Demeter can reduce coupling.

- We can nest comprehensions.

- It can sometimes be useful to discard the current item in a comprehension using a dummy reference, conventionally the underscore.

- When dealing with one-based collections it’s often easier just to waste the zeroth list entry.

- Don’t feel compelled to use classes when a simple function will suffice. Functions are also objects.

- Complex comprehensions or generator expressions can be split over multiple lines to aid readability.

- Statements can be split over multiple lines using the backslash line continuation character. Use this feature sparingly and only when it improves readability.

- Object-oriented design where one object tells another information can be more loosely coupled than those where one object queries another. “Tell! Don’t ask.”