Introduction

The term “psychonetics” was introduced by the Japanese businessman, innovator and futurologist Tateisi Kazuma, who originally mentioned this term at the international futurologist conference in Kyoto in 1970 [1].

Tateisi Kazuma suggested that information technology (“cybernetics”) would eventually be replaced by biotechnology (“bionetics”) and that the latter would eventually be replaced by “psychonetics”, which is a technology that relies on the exclusive properties of the human mind in addressing technological goals [25].

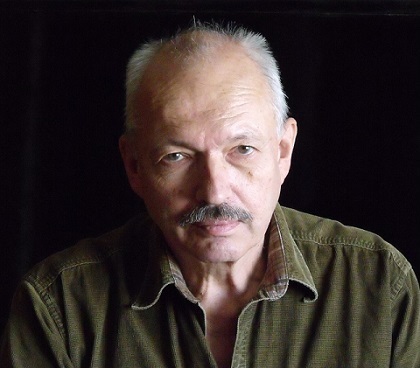

In the late 1990s, the term “psychonetics” was selected [1] by Oleg Bakhtiyarov, an ex-USSR scientist, as the best term to name the terminology, methodology and group of practices of the research in which he was involved.

Oleg Bakhtiyarov described psychonetics as "an aggregate of psychotechnologies, based on the unified methodological foundation, directed towards resolving tasks defined in a constructive manner, using exclusive properties of mind". [3]

Bakhtiyarov wrote several books on the subject [1, 2, 3] and created a few organizations (such as the University of Efficient Development) [9, 10, 11] to provide training in psychonetics to the public.

Despite these activities, however, the openly available publications on psychonetics are surprisingly sparse, particularly with respect to introductory and beginner’s material.

This book attempts to address some of this gap by providing a simplified overview of the history, concepts, practices, educational process and applications of psychonetics.

Kiev Institute of Psychology and its 1980s research

The terminology, practices and methodology of Bakhtiyarov’s psychonetics originated from the research conducted at the Kiev Institute of Psychology, USSR, in the 1980s [1, 17, 16, 19].

Oleg Bakhtiyarov was part of the original team of researchers of this institute. He was involved in developing the majority of the techniques discussed in this book. For example, Bakhtiyarov originally presented the concepts that were later summarized as the “deconcentration of attention” at the 6th All-Soviet Union Congress of Psychologists Society of the in 1983 in his thesis titled “On methods of regulation of an operator’s psycho-physiologic condition”.

One group of tasks that the Kiev Institute of Psychology was addressing was enabling the human mind to efficiently address the challenges of operating new technological equipment.

An example of such a challenge was the task to enable nuclear power plant operators to monitor many indicators simultaneously in an efficient manner [2].

There was also a task to resolve the problem of monitoring radar screens for a long time. Most individuals monitoring a radar screen continuously for more than 30 minutes start to see things that are not there or start to ignore real targets. There was a requirement to develop techniques to monitor a radar screen for hours without undesirable side effects [2].

According to Bakhtiyarov, the greatest and also the last achievement of the mentioned research team as a government organization was developing “the methods of retaining self-control and performance in altered states of consciousness caused by an unknown factor”. [19]

The “unknown factor” in their research was a hypothetical mind-affecting weapon. The idea for such a weapon was based on an assumption that the human part is the weakest component of any complex system. Therefore, both the USSR and the USA invested resources in developing a weapon that would affect the human mind while having little to no effect on equipment. Although there is currently no proof of whether such a weapon was successfully developed, the task was set to preemptively develop psychological techniques that would enable an individual to resist such a weapon [19].

Another exotic example in which such “methods of retaining self-control” were supposedly applied is situations in which Soviet cosmonauts experienced occasional hallucinations during early space flights.

According to Tatiyana Kovalyova, a lecturer from the University of Efficient Development [9], there were incidents in which cosmonauts reported seeing their relatives visiting them on the space station or a dog running around. Such hallucinations were attributed to the new and unknown factors associated with space travel such as extreme accelerations and zero gravity.

The task of the Kiev Institute of Psychology team was to develop psychological techniques to enable cosmonauts to remain calm and continue to perform their duties regardless of any hallucinations they might be experiencing.

Separating technology from ideology

According to the information provided by Bakhtiyarov [1, 16, 17] and the lecturers of the University of Efficient Development [9], the team in which Bakhtiyarov worked studied any technique or area that appeared to be mind-affecting in an attempt to accomplish their tasks. Studied subjects included hypnosis and self-hypnosis, the use of biofeedback devices, traditional Buddhist and yogic texts and practices as well as books of mystic writers (such as Carlos Castaneda[51]).

An important factor that influenced the research was the competition caused by the Cold War. This competition was strong and thus allowed the removal of all artificial barriers, including social, ideological and even traditional science barriers [19]. The only factor that mattered was the results. This period was likely the most notable historical period in which the question of psychological human possibilities was addressed with such energy, resources and dedication by the strongest governments in the world.

“All ideological barriers were removed for us,” Oleg Bakhtiyarov says [16] concerning his time as a researcher at the Kiev Institute of Psychology in the 1980s. “When we once had an ideological conflict with the management of our institute, a military admiral arrived from the Section of Practical Problems, Academy of Science, who was supervising our research and forced the director to sign the required papers.”

Although the researchers themselves were shielded from the USSR’s official ideology, the resulting practices were not. These practices were supposed to be delivered to the end-users, including cosmonauts, military special forces and operators of important equipment. Therefore, all potential ideological conflicts had to be avoided.

The philosophical part of the USSR’s official ideology was dialectical materialism [37], which claimed the primacy of matter over consciousness and generally denied religious and mystical subjects as being “opium for the people”.

The problem that the researchers faced was that most of the original practices that they studied were ideologically biased; in many cases, they were based on a religious or mystic ideology. According to Bakhtiyarov, the main part of their work was to separate working technology from an ideology to which it was connected [19].

Although the task of extracting unbiased technology from ideologically biased practices was difficult, the resulting techniques gained unmatched flexibility and their area of applicability significantly increased.

Psychonetics as a technological approach in psychology

“We developed practices that enabled individuals to act under the model of some unwanted influence,” Bakhtiyarov says about his work on “the methods of retaining self-control and performance in altered states of consciousness caused by an unknown factor” [19].

“The model was simple. An individual performs some arithmetic calculation, such as subtracting 17 from 10000. Then, 17 again from the result and again.”

“At some point, he is administered nitrous oxide and sees a hallucinatory image. His task is to continue the calculation. However, he does not have means to continue the calculation because there is no logic anymore; thinking does not work.”

Although the individual loses regular consciousness, special training enables him or her to continue the original task regardless of the altered mental state.

“The individual leaves this state [of mind] after 3-4 minutes. During this period, he performs 2-3 calculations. The speed clearly drops, but it still fits in the proper sequence.”

It might not be easy to explain how it is possible for a mind to continue consciously performing arithmetic tasks when it is officially unconscious. However, that team of researchers was seeking solutions to their tasks rather than explanations concerning the observed phenomena. The researchers’ approach could be called “technological”.

A technological approach differs from a scientific approach in the sense that the former does not claim to develop explanations as long as there are reproducible steps that can be followed to reach a predictable result.

In the case of psychological and cognitive research, the technological approach has its benefits because a human mind seems to be capable of producing many more experiences than it is capable of explaining.

Explanations tend to assume the role of a censor, thus preventing experiencing phenomena that do not fit these particular explanations. Explanations could also conflict with existing ideologies such as governmental, cultural, individual or religious ideologies as well as with dominating scientific theories. Strict avoidance of unnecessary ideological (or rather, ontological) constructs allows such conflicts to be avoided.

The collapse of the USSR in 1991 caused the described research (and many others) to stop because of a nearly four-fold drop in scientific funding in the region [35].

After the collapse, psychonetics was developed, maintained and popularized by enthusiasts such as Oleg Bakhtiyarov outside of a strict academic environment and apparent government interests (at least until recently [24]).