As Below, So Above

Stand at a stone circle, and see with different eyes. At your feet, as you know, are Underwood’s patterns, a network of lines weaving and interweaving across the surface of the grass; but now you see them, as glowing wires, as twisted cables gleaming in their own light, the different types of line distinguished by different colours, different hues.

But this is not all. The stones themselves glow with light, their colours and intensities changing and pulsing as you watch. The ground itself is glowing, concentric rings of muted colours spreading out from the centre of the circle. Above the ground there is activity too: sparks of coloured light jump from stone to stone around the circle, travelling along taut wires of light, like messages chattering from stone to stone. Occasionally, all this activity comes to a climax: the top of one stone gleams brightly for a moment as a huge pulse of energy emerges from it and disappears into the distance, like a firework rocket travelling along an almost invisible horizontal wire. A message of some kind, travelling from one site to another - or a pulse in a nerve of the body of the earth itself.

As you can see in the image above, Underwood’s patterns are only a part of the picture of sacred sites that can be constructed from recent research. (The image is more than an analogy, by the way: several dowser-psychometrists have described the sites to me in these terms; and I remember how a friend of mine, working with me at Stonehenge, suddenly discovered he could ‘see’ the lines as bright silver ‘wires’ winding and twisting just below the surface.) A lot has been going on since Underwood’s time, and very little has been published - which is not all that surprising, since until recently most archaeologists dismissed this kind of work as the furthest extreme of the ‘lunatic fringe’. But attitudes are changing even within the narrow confines of academic archaeology; and this new research is of still more value when seen in the wider context of the relationships between places and the forces of nature.

Underwood found his patterns below ground, or just at the surface. Like many of his contemporaries, that seems to be the only level at which he looked for anything. However, even in his time it was known that points or places could be polarised or ‘charged’, in a dowsing sense, in relation to others; and this includes a variety of types of polarisation at sacred sites. Some of these charges are, like Underwood’s patterns, on points at or below the surface: others, though, are above.

It seems, from what little published evidence there is, that the first above-ground charges to be found were on standing stones. I’ve tested this for myself, both on my own and with my students: it does seem that standing stones are polarised in relation to the ground around them and, in stone circles, polarised in relation to each other. It’s easiest to describe this polarisation in terms of charge, but that isn’t quite accurate in a physical sense, and we don’t actually know what it is. There does seem to be a physical component involved in it somewhere, for John Taylor and Eduardo Balanovski, working with the dowser Bill Lewis in 1975, found a ‘significant’ distortion in the local geomagnetic field around a standing stone near Crickhowell in South Wales. The normal strength of the geomagnetic field in that area has a value of about half a gauss; the maximum deviation expected was no more than a few hundredths of a gauss, but immediately around the stone the local field had more than doubled in strength - ‘significant’ indeed!33

According to correspondence with one of my colleagues, Taylor has since claimed that the results were ‘inconclusive’; and this seems to be because he, like Underwood, assumed that the strength of any pattern would be fixed, and it was not. But Lewis told me that he had warned Taylor from the start that the field-strength rose and fell on a regular cycle. If scientists are to research these fields, their work has to be truly scientific if it is to be of any use: preconceptions of any kind, particularly in this area, are likely to make such research unscientific, and thus useless. (Since Taylor’s early work, a number of other physical research studies have been done as part of the Dragon Project, with probably more significant results and implications: but we will leave a detailed look at these until later.)

Taylor’s work was also limited in that, again like Underwood, he assumed that any polarity around the stone must be solely electromagnetic. This is an assumption which forty-years’-worth of their own research into the physical factors of dowsing has taught dowsers to beware.34 Most dowsers would agree that an electromagnetic component is involved, but many of those I’ve discussed the matter with have suggested that this may only be a side-effect of something, some energy, on what they would call another ‘level’. Each time someone tries to pin down any ‘cause’ in dowsing to one specific physical mechanism, it suddenly stops and reappears as some other apparently physical mechanism. This effect is well-known in other research on the mechanisms behind psychic phenomena, particularly psychokinesis: it’s sometimes called the ‘bloody-mindedness’ of those phenomena.35

The polarities seem to represent something more complex and less tangible than purely physical energies, though the physical level does come into it somewhere. But though we don’t know what they are, we can at least distinguish between the various types and the relative polarities of each type. The most common form of polarity seems to be related to the Chinese duality of Yin (or ‘female-principle’) and Yang (or ‘male-principle’). For practical purposes these are usually referred to as ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ respectively: but note that this does not mean that Yang is ‘better’ than Yin, it’s just a useful way of labelling them for practical dowsing work.

The usual way of picking up these relative polarities or charges in dowsing practice is to use a pendulum in one hand, and rest the other hand on top of the standing stone (or whatever else it is that is being tested). The pendulum’s ‘neutral’, for me at least, is when it is swinging backwards and forwards in an even oscillation; as the dowser touches the top of the stone with his or her other hand the pendulum gyrates, and the direction of the gyration is used to imply the polarity of the stone at that time. In my case, a clockwise gyration of the pendulum is positive, and anticlockwise negative, but this does vary from one dowser to another.

Few of the polarities on standing stones stay the same for long, particularly at stone circles. I did a week-long study of the morning, afternoon and evening polarities of the stones at Rollright in the summer of 1973, and only about a dozen of the seventy or so stones there maintained the same charge for the whole week. Most of them changed from hour to hour, and many of them had minor changes occurring on a twenty- to twenty-four-second cycle. But churches, and Christian sites in general, are different: the altars of those that I’ve tested are almost invariably positive, and stay that way. The exception to this is that many Lady Chapel altars are equally fixed at negative. Church buttresses - particularly at the east ends, for some reason - are more like standing stones, as their charges wander somewhat; and other points within churches that tend to be strongly polarised are fonts and piscinas.

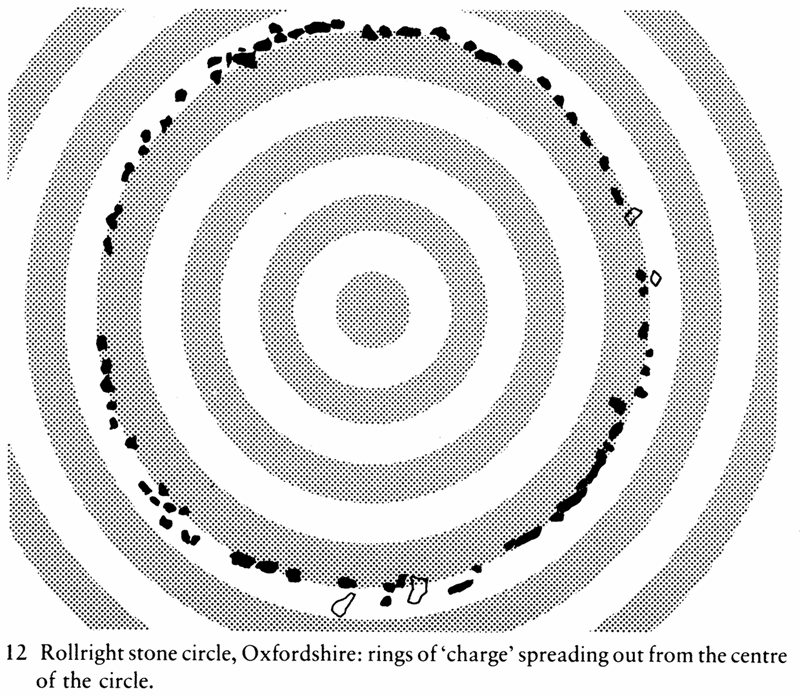

Whole areas can also be polarised in relation to others, mainly at ground level, but possibly above or below. During that survey at Rollright, using angle rods, I discovered a set of concentric rings of alternating charge: the rods crossed on passing through the line of the stones, opened out again further towards the centre of the circle, and repeated this ‘opening and closing’ to give seven concentric rings around the centre. It would seem that the polarities here are relative rather than the more absolute positive and negative, for I found that if I started with rods crossed, they opened out as I passed through the line of the stones, and so on in reverse to the centre of the circle. The effective pattern is similar to what Underwood called a ‘halo’, a set of concentric rings around a major point, such as the intersection of nave, chancel and transepts in a cathedral; it’s also like a multiple version of the pattern produced in the Creyke system of depthing described earlier.

This alternation of charge at Rollright continued outward from the circle for at least three more alternations; it is likely, from the feel of it, to have gone further, but obstructions like hedges and the fast-moving traffic on the road hard by the circle made it difficult to trace more of the pattern. I have since found a similar, though weaker, pattern at Gors Fawr stone circle in Pembrokeshire; I haven’t yet been able to test for it at other circles, but other dowsers I’ve talked to have reported similar effects at some of them. I haven’t yet studied area polarisation in churches either, partly because most of the significant old churches are still in daily use: but it would be interesting to see what patterns are to be found there.

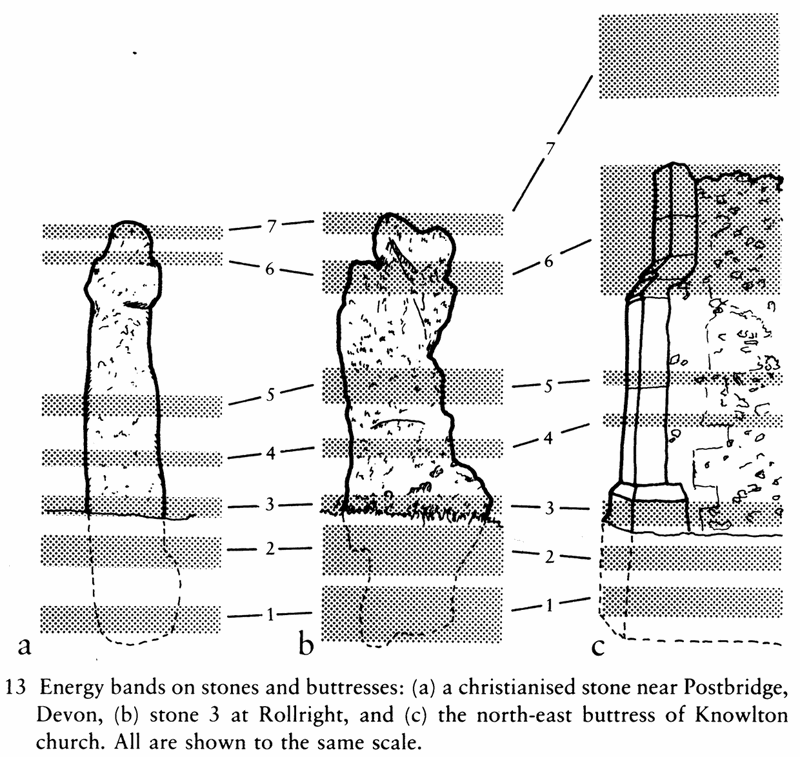

In the same way that there tend to be concentrations of charge at various points on a site, there tend also to be concentrations at specific points on the structures of those sites - such as church buttresses and, particularly, standing stones. These concentrations showed up in Taylor’s research on that stone at Crickhowell, as narrow bands of double-strength geomagnetic field running horizontally across the stone at various heights upon it. These bands move up and down a little on the surface of the stone, following what appears to be a lunar cycle: and because Taylor was apparently expecting these bands, once he found them, to stay still, that may be another reason why he said his results were ‘inconclusive’.

There are seven of these bands on most large standing stones; smaller stones, below about four or five feet, may only have the first five, though there are a number of exceptions to this general rule - the smallish wall-stones in the chambers at Belas Knap long barrow in the Cotswolds, for example. have all seven bands. Two of the bands are usually below ground level, and the third just above or below the surface; the top band will be at or very close to the top of the stone, and the remaining one or three bands (or however many the stone has) are usually spaced irregularly over the rest of the height of the stone.

All seven bands, according to several researchers I’ve talked to, are tapping points into a spiral release of some kind of energy that moves up and down the stone, following that lunar cycle. The cycle appears to control, the release of this energy in a sine-wave form, the zero-points of the cycle occurring on the sixth day after New and Full Moon.

Underwood noticed a similar, if not identical, cycle guiding regular changes in some of his secondary patterns; and, as he pointed out in Pattern of the Past, this coincides precisely with the structure of the Celtic calendar, at least as described by their first-century bronze ‘tablet’ found at Coligny in France at the end of the last century.36 According to the tablet, the months started on the sixth day after New Moon, and were divided into two fortnightly periods (hence the English ‘fortnight’, a fourteen-night); the New Year started on the sixth day after the first New Moon after the spring equinox. (The West-European Easter is a Christian takeover of the old pagan New Year festival, which is why Easter is a ‘movable feast’.) Underwood stated that the cycle in his secondary patterns repeated its zero-points almost to the second each fortnight; and another researcher, Andrew Davidson, timed the zero-points of the cycle of the spiral energy-release round a set of standing stones in Scotland to within seven minutes.37 Either way, a measurable cycle of that accuracy - better than most clocks until well into the 20th century - would seem to be a useful guide for any pagan calendar: so the parallel with the Celtic calendar may be more than ‘mere coincidence’.

The spiral feeds energy from the ground to the sky during one half of the cycle, and feeds from the sky to the ground during the other half. The bands on the stone seem to connect the stone into this flow of energy, apparently to control it: they seem to plug the stone into energies both above and below ground, while the stone itself both marks and is the right point through which the interchange of energies can take place. The bottom three bands connect the stone into the energies below ground; among other things, they seem - from my research results at least - to connect up in some way with Underwood’s patterns, but I’ve not been able to work out what the connection is. The remaining bands connect up with other energies, or networks of energies, above ground; and in the case of the fifth and seventh bands this connection, as far as many dowsers are concerned, produces some interesting side-effects.

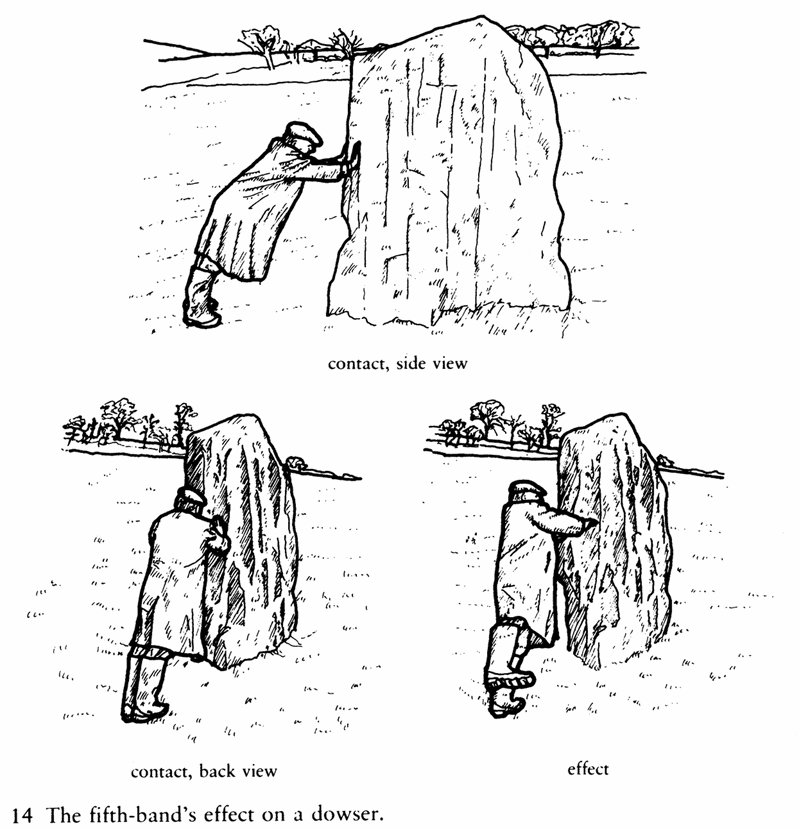

The effect of the fifth band on the dowser may have given a standing stone in Gloucestershire its name: the Twizzle Stone. When a dowser leans against the level of the fifth band on a stone or buttress, the band somehow affects the dowser’s balance, producing an effect which feels like a slow and gentle push to one side or the other. According to the skill of the dowser (and, it must be admitted, more subjective factors like a sense of showmanship), this sense of ‘being pushed’ can be increased until it looks as if the dowser has been thrown to one side by the stone. The same lunar cycle controls the strength of this effect: the thrust waxes and wanes, and reverses, in the same way as the spiral release of energy around the stone. Around First and Last Quarter the response tends to be weak and unclear, while on the day before New and Full Moon there is often no doubt at all that the effect is there.

The usual procedure is to use a pendulum to find the position of the band, using the free hand as a pointer to move up the surface of the stone. Then place both palms flat on the surface of the stone at this point; lean against the stone, resting your weight on your palms, and relax. By ‘relax’ I don’t mean ‘go floppy’: rather, I mean that you should allow the tension in your muscles to ease evenly, and - perhaps more important - to relax and clear your mind of ‘doing’, analysing, thinking. If you’ve done this right, and if the conditions are right, ‘upright’, in the subjective sense, suddenly ceases to be upright, and you’ll roll to one side or the other. The direction of this apparent thrust will remain the same, for you at least, until the end of that lunar cycle; for the next fortnight it will reverse; and so on. Different people are pushed different ways, for some reason, and different stones may induce different apparent thrusts, so don’t assume that if it works for you in one way at one place it must therefore be the same for everyone everywhere.

I once showed Paul Devereux, editor of The Ley Hunter magazine, how to find this fifth band effect, working on one of the main stones at Avebury and on the tower on top of Glastonbury Tor. Since he hadn’t been able to dowse before this time, his comments are interesting. He said that the immediate effect of the fifth band was ‘like when you’ve had just one drink too many’: it was a feeling that hit him as soon as he made contact, and this sense of a loss of balance developed, in a couple of seconds, into a definite ‘push’ to one side. It’s interesting to see how specific this effect is: on the west-end buttresses of the tower on Glastonbury Tor it could only be felt from a narrow band about six inches high and around four feet off the ground, while it couldn’t be found at any height on the east-end buttresses. Since the latter were only put up to support the tower after its church had collapsed in an earthquake, and were thus not part of the original layout of the church, that perhaps isn’t so surprising.

Another often-reported effect at the stones, probably from contact with this band, or the seventh, is the feeling that the stone is rocking or moving or, as one of my students put it, ‘jumping about’. Again this is a subjective feeling, since the stones are usually firmly rooted in the ground; but a lot of people, dowsers and non-dowsers, have felt it. The late Tom Lethbridge, in his book The Legend of the Sons of God, described how this effect occurred when he tried to date the stones of the Merry Maidens circle at Lamorna in Cornwall:

As soon as the pendulum started to swing, a strange thing happened. The hand resting on the stone received a strong tingling sensation like a mild electric shock and the pendulum itself shot out until it was circling nearly horizontally to the ground. The stone itself, which must have weighed over a ton, felt as if it were rocking and almost dancing about. This was quite alarming, but I stuck to my counting…38

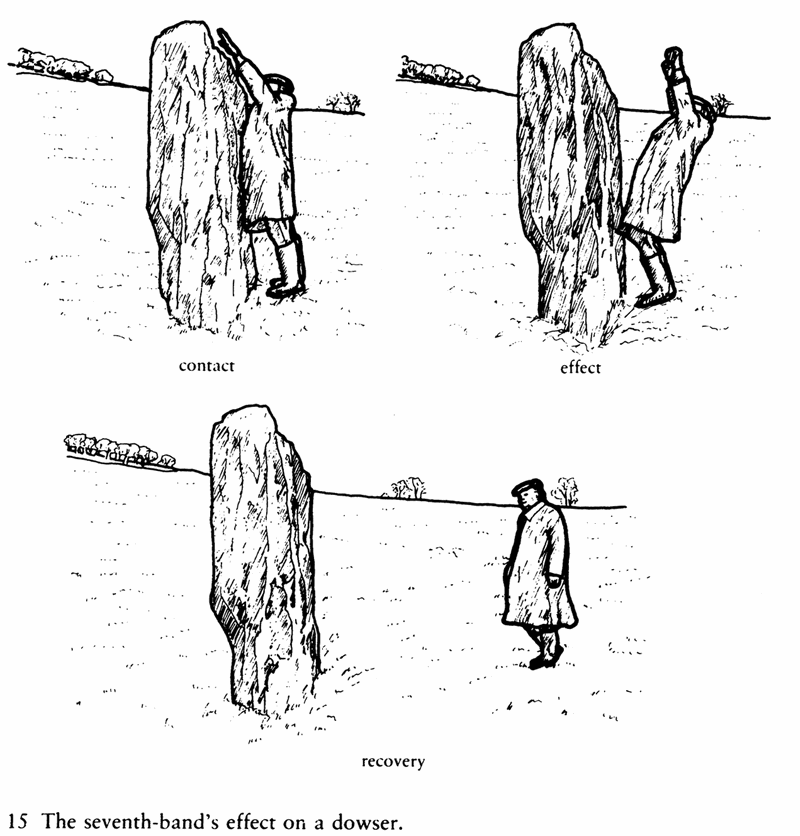

This ‘tingling sensation like a mild electric shock’ is also one of the characteristics of the seventh band’s effect on the dowser. With a skilled dowser this can be spectacular: as he touches the band with his fingertips, the energy released triggers off a violent reflex contraction of the back muscles, throwing him backward as much as ten or fifteen feet. Even non-dowsers can often feel the energy at this point as a slight warmth or tingle, which may account for the name of another standing stone in Gloucestershire, the Tingle Stone, near Avening.

My strongest experience of this seventh band reaction was at Avebury, when a friend and I were trying to find the former height, by dowsing, of the Obelisk Stone, which once stood in an inner part of the southern circle there. The stone isn’t there now - it was pulled down and destroyed in the seventeenth century - and all that remains is a large concrete marker. Because of this, we thought we would have to work at maximum sensitivity if we were going to find the memory (so to speak) of the original shape of the stone. We used a ‘booster’ technique, in which a second dowser - to use a radio analogy - acts as a series amplifier on the signal that the first dowser receives: we thought that the signal would be too weak to be noticed if we didn’t do this.

We were wrong, of course. Using a pendulum in one hand, I used my other arm as a pointer, to find the former height of the tip of the stone. We did, at about seventeen feet: but at the same time we found the ‘memory’ of the stone’s seventh band. It was quite a reaction. I’m not quite sure what happened then, since all I remember is jumping back with the shock, but my wife, who was watching at the time, tells me that my arms went out wide, and I only just managed to keep upright. My friend went sprawling on the ground about ten feet back from where he started, for, being ‘booster’, he’d caught the brunt of what I’d managed to dodge. It was several minutes before either of us recovered enough to start work again.

Many dowsers have had experiences in a similar vein, so it’s not surprising to find them wary of working at stone circles and other sacred sites. I remember a student of mine overtired herself working on one of the stones at Rollright: she suddenly found herself having a giggling fit after tripping over a tiny piece of chervil, which she swears wrapped itself round her ankle; she only sobered up - and instantly at that - when we helped her out of the circle. Another dowser reported finding her pendulum doing a miniature version of the Indian Rope Trick when she dropped it after working at the same circle too long. One medical dowser I talked to warned me that the energies involved are capable of damaging human metabolism: so it is important to know what you’re doing when you’re working at these sites, and to treat the energies with some caution. As in other fields, casual dabbling may be dangerous.

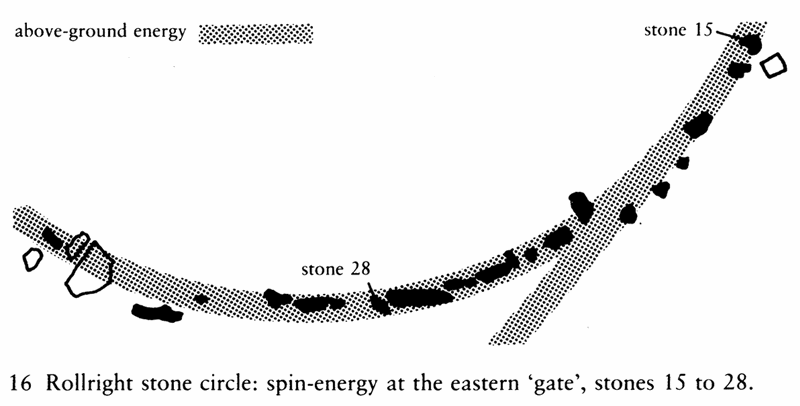

This was brought home to me in the early days of my experiments, when I borrowed a teenager as a helper at Rollright. We had been noticing for some time that each time we crossed the line of the stones with angle rods, the rods reacted in a way that implied there was some kind of energy jumping from stone to stone around the perimeter of the circle, moving in a sun-wise direction about three feet off the ground. Basically, this energy was just spinning round the perimeter of the circle; but there are two points at Rollright which seem to be like gates, in the sense that the line of the stones breaks so that as you walk round the circle just inside the line, you will find yourself going outside the line at these points. The interesting thing was that the line of the energy became double at these two points, one moving round the circle as usual, but the other part apparently moving off at a tangent to the circle. We thought that one of the stones close to the eastern ‘gate’ might be the ‘gate-latch’, so to speak; so my helper stood in the gateway, pendulum in hand, and I tested the gate-latch stone with my pendulum. The result, for both of us, was instant migraine.

It wasn’t until quarter of an hour later that the headaches began to clear: intangible and immaterial though it might have been, the massive pulse of energy we’d released through the gate had been real enough to us. Since that experience, I’ve been careful to learn basic protection techniques and, as far as possible, to work only with people who have also learnt them. I’ve also learnt the value and importance of feeling for when something is wrong, or about to go wrong: but unfortunately these things can only be learnt through practice, and through sometimes bitter experience. If you don’t already know what I mean by this, you’ll have to find out for yourself - there’s no other way that I can show you.39

I’m still not sure what happened then, for by the time that we had recovered enough to start work again the energy pattern around the circle was exactly the same as before our experience - pretending, as it seemed, that nothing had happened. As far as I can work out, though, this aspect of the circle resembles a cyclotron: some kind of energy, possibly derived from the blind spring at the centre of the circle, and implied by the concentric ‘haloes’ round the centre that I described earlier, spread outward from the centre, and was collected at the perimeter of the circle, to be stored there by spinning the energy from stone to stone. By inserting a small amount of energy into any of the gate-latch stones - which is what I had done, in testing the stone - the relevant gate was opened, releasing all the stored energy in one go: and that was what had flattened us in its passing. I’ve never been able to work out what happened to the other energy patterns of the circle during this momentary convulsion; and since, for obvious reasons, I’m unwilling to repeat the experiment, I probably never will.

The interesting thing here was that the pulse of energy, whatever it was, seemed to leave the circle at a tangent to the line of the stones, travelling in a dead straight line. I think it went about six miles to the south-west, to a stone called the Hawk Stone, and then split off in two different directions from there - or rather, that’s what the dowsing results implied, because it doesn’t quite make sense according to the map. The important point was that not only did this pulse travel straight across country, but a faint continuous line marked out its course, in a dowsing sense, above the ground. This line was the continuation of the tangential line coming off the spin at the gate, the line which we had found before we had accidentally released the energy pulse. It started, like the spin, at about three feet off the ground, and shortly after leaving the circle had widened from its original two feet width to about six feet, which seemed to be its normal’ width for what I could track of its course across country.

As I found more of these lines travelling above ground to and from various stones at Rollright and at other sites, I called them ‘overgrounds’ in order to distinguish them from Underwood’s patterns underground. The dowsing techniques to find them are exactly the same as for Underwood’s patterns, except that you have to remember to keep in mind that you’re looking for patterns above ground, not at the surface or below. Soon after I had found these overgrounds, I discovered that other dowsers had known of them for some time because of their effects in a different field of dowsing research; but they referred to them by another term - ‘leys’ - which, as we shall see shortly, is a particularly important one in the history of the study of sacred sites.

Mirroring Underwood’s patterns, these overground lines connect in some way with those bands or tapping-points above ground on the stones; though again, as with Underwood’s patterns, they don’t seem to connect directly, but rather relate to them by some complicated linkage or relationship that I don’t yet understand. The different bands also seem to have different functions: all of them deal with these overground communications, but the fifth and seventh bands seem to hold or diffuse the pulses in some way, while the sixth band tends to deal with long-distance communications from site to site, and the fourth band to deal with local communications within the site or the local area. These are tendencies rather than rules, though: from my results at least it seems that every band can perform every function.

The local communications, the pulses jumping from stone to stone on a site, show up in other ways that we’ve come across already. At stone circles, one set of pulses jumps from stone to stone either clockwise or anticlockwise round the circle, forming the apparent spin of energy; and other pulses, jumping around in a less obvious sequence, change the polarities of the stones on their regular and irregular cycles. From a dowser’s point of view, watching these pulses move around on a complex site like Rollright, it is no exaggeration to describe the site as ‘living, breathing, pulsing’.

But to me it is the long-distance overgrounds, or rather their ‘carriers’, which are particularly interesting. There are a lot of them: the main outlier at Rollright, the King Stone, had more than a dozen linked to it the last time I checked, and there may well be more. There are probably more than a hundred of them linking in to the whole Rollright complex, if we include all the minor and irregular links; there are so many of them that an image of stone circles and standing stones as stone ‘telephone exchanges’ springs to mind.

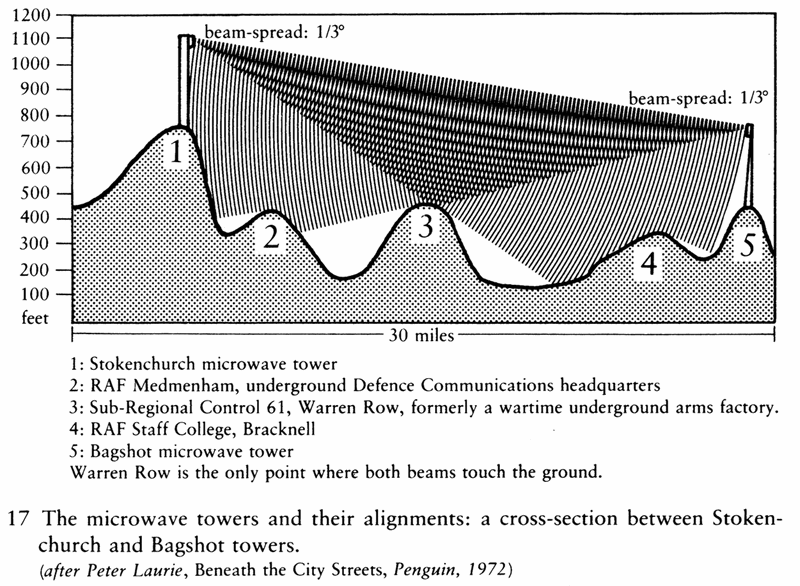

That image may not be as fanciful as it seems, for a striking analogy can be drawn between the overgrounds and present-day microwave telecommunications. Much of Britain’s telephone traffic is carried on microwave links between various towers dotted around the country: the best-known of these are the concrete Post Office towers in the centres of London and Birmingham, but there are about a hundred other towers and steel pylons in the chains that run from end to end and side to side of the country. If you look at these towers, you can see ten-foot-high ‘horns’ mounted high up on them: these are the main microwave aerials. Each horn can transmit several thousand telephone conversations at the same time, which is why the towers were built in the first place; and it transmits these as modulations of a single narrow beam that jumps from one tower to another along the chains. The beam from each horn is a cone with less than one-third-degree spread (the smaller ‘dishes’ on the towers aren’t quite so accurate), and because the horns are placed high up on the towers, that are themselves usually built on high ground, the beams rarely touch the earth.

This is the really ingenious part of the design of the British microwave network, for it is something of an open secret that the ‘secret’ Government centres are built on or under those hills that the beams just touch. For example, the only hill that the beam between the towers at Stokenchurch (where the M40 crosses the Chiltern ridge) and Bagshot Heath touches has an ex-World-War-II arms factory hidden underground beneath its summit, now converted to one of the government’s semi-secret ‘Sub-Regional Controls’. The same beam passes directly over the RAF Staff College at Bracknell and the defence communications headquarters (again underground) at Medmenham. This hidden aspect of the towers’ function was discovered by a pacifist group called ‘Spies for Peace’ during the 1950s.40

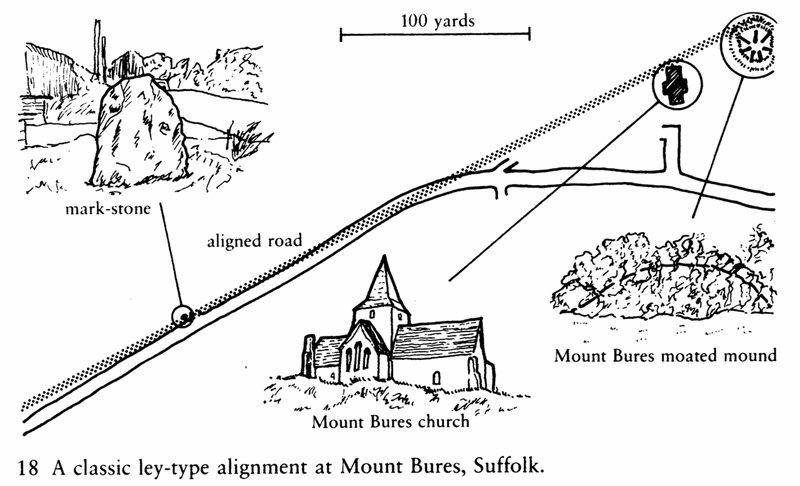

Political implications apart, the interesting point here is that the major sites of the network, the towers, were placed on carefully selected hills so that minor sites on other hills could tap into the beams: all the hills align. Hence the analogy with the overgrounds and the sacred sites, since they too form alignments of major and minor sites along the same straight overgrounds. Major sites such as stone circles and large standing stones are terminal points for each overground, analogous to the microwave towers; and spaced irregularly along the overgrounds are the minor ‘tapping points’, like the small mark-stones that you can see in many places set into the side of the road.41 Like the small microwave dishes on the hills, they aren’t placed as randomly as they seem; and like the dishes, they are there for a reason, though not, I think, the same one.

This matter of alignment, or apparent alignment, is well known in the study of sacred sites. In recent years a lot of research has been done on inter-relationships of certain types of sites along astronomically significant alignments,42 but much of this was pre-dated by the work of Alfred Watkins and the members of the Old Straight Track Club in the 1920s and 1930s.43 It was actually my interest in Watkins’ leys that started me dowsing in the first place, because I had wondered if it was possible to find and check them by dowsing. Since I couldn’t find any dowsers to help me at the time, I taught myself to dowse; but I couldn’t find any leys by dowsing then, and anyway my interest was soon caught by Underwood’s work. It wasn’t until I had done some work on overgrounds that I realised there was a possible connection between dowsing and leys - but that’s something I’ll come back to shortly. For the moment, we need to look at Watkins’ leys and the concept of the alignment of sacred sites.

Watkins’ first essay on leys, Early British Trackways, Moats, Mounds, Camps and Sites, was written with obvious excitement in the short period between June 30th 1921, when he had his first clue (or ‘vision’, as some later writers have put it) of the ley system, and the September lecture on which the essay, published the next year, was based. His thesis was that the pre-Roman trackways of Britain were constructed in straight lines marked out by sighting from major intervisible points: mountain peaks in high districts, and hills, knolls or artificial mounds in lower ones. The trackway itself was marked by a variety of secondary points, also intervisible, and deliberately designed to be picked out visually from the surrounding countryside. In addition to using standing stones and the smaller mark-stones (which are natural boulders foreign to the area) as markers, the ancient surveyors - according to Watkins - constructed mounds on intermediate ground, cut away notches where the tracks crossed ridges, and made cuttings and causeways where the tracks crossed rivers. These water-points on the tracks were sometimes visually assisted by being banked up into a ‘flash’, so as to glint in the sunshine when seen from a point higher up on the track. The tracks didn’t necessarily run the whole length of the sighting line from mountain peak to mountain peak, they just used those parts which were practical for trading purposes.

It was clear to Watkins that the mark-points must also have had some religious significance, for sacred wells, stone circles and known sacred groves are also primary or secondary mark-points on the ‘old straight track’; and when the Church took over, it also took over the old sites as sites for their new churches. The Romans before them took over parts of the old track for their own purposes, using them as foundations on which to base some of their own not-so-straight roads; we have to realise, said Watkins, that the old straight track was as old to the Romans as their roads are to us. Watkins derived his term ‘ley’, which he used to describe the old straight track, from its frequent appearance in the names of places along the tracks.44

Over the next few years, Watkins’ thesis changed a little, becoming more complex and sophisticated. In his most important book, The Old Straight Track, published in 1925, the different traders’ tracks are identified by different groups of place-names - ‘white’ or ‘wick’ for salt, for example, and ‘knap’ or ‘chip’ for flint - and the Beacon Hills are added to the list of mark-points. By 1927, when he published his Ley Hunter’s Manual, the list of mark-points had grown, in their order of reliability, to the following: prehistoric mounds (except where closely clustered together), moated mounds, wayside mark-stones (where distinguishable from casual ‘erratic’ stones), circular moats, castle keeps (usually on old mounds), Beacon Hills and similarly named mounds (like One-Tree Hills), wells with traditional names, old churches (especially if on a mound or other evidence of prehistoric use of the site, or with certain types of related folklore), ancient crosses, alignments of road or trackway, fords, traditionally-named tree-groups or single trees (especially if Scots Pine), hillside notches, and crossroads, zigzags and other road junctions.

A map will only show some of these types of site aligning, say four or five good mark-points in ten miles, and that might only be ‘coincidence’. It was only in the field that ley-hunting made sense, for on a chance alignment no further sites would be found, whereas on a ‘real’ ley you would find unrecorded mark-stones in the hedgerow, causeways through ponds that blocked the ley’s course,45 paired gateways where the line crossed a road, or other details like confirmatory folklore about tunnels or ‘the old straight road’.

The possibility of finding these little confirmatory clues, combined with the whole sense of adventure and discovery, helped to make ley-hunting into one of the great popular crazes of the 1920s and 1930s. But if it was popular with the ramblers who walked the leys, it was not at all popular with the archaeologists of the time. The Diffusionist theory, which maintained that all culture and civilisation came out of the ‘fertile crescent’ of the Tigris and Euphrates, had just been nicely established as ‘fact’; it seemed to prove that the life of early man in Britain had been, to use Hobbes’ famous description, ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’.

In this view, the first properly surveyed and engineered roads in Britain were those of the Romans; the only roads prior to that had been mere trackways, the old and winding ridgeways and drove-roads. Watkins’ leys had to be absurd, to the archaeologists, for they implied the need for a complex culture and technical ability in at least one section of the population in prehistoric times - and this concept could in no way be made to fit into the orthodox archaeology of the time. The archaeologist O.G.S. Crawford said then that Watkins’ work was ‘valueless’, ‘based on a misconception of primitive society and supported by no evidence’; and this statement it still quoted, fifty years later, by writers like Glyn Daniel and W.G. Hoskins, as proof that Watkins’ work was and is ‘valueless’. And that, they say, is final.46

But archaeology itself has undergone some revolutionary changes in the last twenty years, and Watkins’ work, whilst not without its flaws, fits more closely into the framework of the new archaeology than can the old Diffusionist ideas. It turns out, ironically, that it was Crawford who had the ‘misconception of primitive society’: the new dates given by improved radio-carbon dating, the fieldwork on archaeo-astronomy and the geometry of stone circles by Thom and others, and the new syntheses by archaeologists like Colin Renfrew and Euan MacKie all point towards a technical ability in Neolithic and Bronze Age man in Britain - particularly of surveying and selecting sites for their topographic properties - that is way beyond the conception of the archaeologists of Crawford’s time.47

Crawford’s statement that Watkins’ work was ‘supported by no evidence’ is interesting, for as far as I can discover no serious study of Watkins’ concept of the ley system has ever been undertaken, by Crawford or by any professional archaeologist.48 Crawford’s comments are still quoted as the final proof that the ley-system is ‘chimerical’; yet Crawford, to my knowledge, never studied the evidence in the field; he dismissed the whole idea a priori because it could not and would not fit his view of archaeology. The supposed archaeological ‘proof’, in fact, is no more than a comfortable myth.

Archaeology is rather fond of myths like these: another one concerns the ‘vitrified forts’ of Scotland and Ireland. A number of forts there have at some time been subjected to such an intense heat that the rocks of which they were built have ‘vitrified’ and melted. In every archaeological textbook that I’ve seen which mentions the subject, it is stated as fact that the forts were vitrified because wooden structures inside and beside them were set on fire by raiding parties. But this is not a fact, this is an assumption: an assumption that is denied by a closer study of the forts. In many cases the structures are more heavily melted at the top, which suggests that the heat came from the top downwards, not upward from the bottom as would occur with a more ordinary fire; and one case in Scotland is simply too big for the orthodox explanation to work, for a half-mile length of the hillside beside the fort was vitrified at the same time. Recent research shows that the vitrified rocks are mildly but unnaturally radioactive; and the few studies that have been done on the temperatures involved - which I’ve never seen quoted by the archaeologists - all state conclusively that no wood-fire can reach anything like the temperature required to turn stone into glass, as happens in the vitrification process.49

We just do not know what melted and fused the rocks of those forts. But as with the non-‘study’ of the ley-system, the archaeologists have, for decades, quoted as fact an untested assumption which turns out to have little or no basis in reality. It’s sometimes useful to remember that while professional archaeological research is usually scholarly and well-disciplined, it is every bit as speculative and fallible as that of the ‘lunatic fringe’ the archaeologists despise. Certainly no archaeologist has the right to say, as Professor Stuart Piggott once did on a television programme, that ‘only professional archaeologists can put forward ideas about prehistory’.

So, to return to Crawford’s claim that the ley-hypothesis was ‘supported by no evidence’, there is in fact a great deal of evidence for the ley-system from both map-work and fieldwork; but most of it has been collected in such a haphazard way and, in many cases, with so little care and discrimination that Crawford did have a point. I know of only one systematic ley-hunting study of a defined area that has been done to date, and that is John Michell’s study of the megalithic sites of the West Penwith peninsula in Cornwall in 1974, published as his The Old Stones of Land’s End. Michell was careful to use only those sites which were known to be prehistoric; several stones modified into Christian roadside crosses did fall into the pattern, but he regarded them as secondary evidence only, on the grounds that they might have been moved from their original sites during the early part of the Christian period.

During the survey he found twenty-two alignments between the fifty-three ‘valid’ sites in the area, eight of these sites being unmarked on any map. These alignments were, he said, ‘of rifle-barrel accuracy’, the sites being aligned precisely centre-to-centre over distance of up to six or seven miles, an accuracy checked both in the field and with a horse-hair stretched over air-photographs of the area. By walking these alignments, Michell found not only the eight previously unrecorded sites, but also found that the sites were precisely intervisible, being placed exactly on the skyline between one site and the next. Both of these aspects of leys had been described by Watkins some fifty years before. This first systematic study of ley-type alignments was, predictably, ignored by the professional archaeologists: their evasive correspondence with Michell on the subject was subsequently published in The Ley Hunter magazine under the ironic heading of The View Over Ivory Towers.50

Two years later Michell’s Lands End work was subjected to a detailed computer analysis by Chris Hutton-Squire and Pat Gadsby, who published their results in the alternative-technology magazine Undercurrents.51 Working mostly from maps, and working to a maximum allowed width of ten metres (but not more than one metre per kilometre), they confirmed all bar two of Michell’s original alignments, and added twenty-nine more. (The two that ‘failed’ did so because of the difficulty of choosing where they both met the Merry Maidens stone circle: the analysis assumed that all lines went to the centre of each site, but Gadsby and Hutton-Squire suggested later that there was a better ‘fit’ if the lines struck the circle at the tangent - which would seem to have some parallels with the spin-effect at Rollright mentioned earlier.) The most striking result was that a rather insignificant stone at Sennen, near Land’s End itself (Michell’s ‘stone 17’), had no less than seven alignments running through it, while on a randomised simulation (to give a figure for chance alignment) that Gadsby and Hutton-Squire also ran through their program the ‘dummy’ stone 17 had only one alignment through it: as they said in their article, ‘this appears to be good evidence of deliberate alignment’.

Their randomised simulation used dummy sites matched to each of the real sites, but placed randomly within the same kilometre square as each of the real sites, so as to produce roughly the same clustering that the real sites showed. This gave a statistically acceptable figure for chance alignment. The real sites produced a number of alignments that was well above the chance figure - statistically, 160 to 1 in the case of the three-point alignments and 250 to 1 in the case of the one five-point alignment - and some of the real lines were indeed of ‘rifle-barrel accuracy’, the sites being exactly aligned with each other, with no appreciable deviation, over several miles.

The other interesting point which the random simulation picked out was that, using the chance figures that it gave, not only are many of the real sites aligned with each other to a greater degree than chance, but other real sites are non-aligned with each other: they have fewer alignments between them than chance would predict. This is an important point in a new understanding of leys, as I’ll explain shortly. Gadsby and Hutton-Squire’s statistical study is the only one to date which, to my knowledge, has handled the data available in anything resembling a scientific manner: there have been other studies, but they have been based on assumptions (particularly about ley-width, length and type of alignment) that no serious student of leys could accept.52

The other problem which statistical studies present is that while they show that many of the apparent alignments must be due to chance, they can’t tell us which alignments are ‘real’, and which are not. So we’re presented with another conundrum: when is an alignment a ley? For that matter, given the apparent non-alignment mentioned a moment ago, when is a ley an alignment? There’s no easy answer.

So here we come back to the whole question of what a ley is in the first place. In Watkins’ original thesis it was a trackway formed between sighted intervisible points of so many incongruous types and of such different periods that it’s not surprising that the archaeologists at least queried the idea. It’s true that the sites do seem incongruous, but if we compare Watkins’ mark-points with Underwood’s sites we find that the two lists are almost identical: a significant coincidence, I think.

There’s also the question of whether leys really are trackways in essence, for whilst sections of road and track do align with other sites, it seems from comments by several recent researchers that the ley - if it is ‘real’ - tends to run down the side of the track rather than down the middle of it. This suggests that the ‘trackway’ aspect of leys was a sort of side-effect or after-thought rather than part of the original design. Many leys make no sense at all as tracks anyway, for they do strange things like dropping over precipices, taking the longest line over marshes, and recrossing the same river many times. Apparently Watkins himself realised the limitations of the trackway hypothesis towards the end of his life, and is said to have been unhappy about the more mystical or magical interpretation of the lines that this implied. Nevertheless, the more mystical or magical interpretation of leys seems to be the one which is preferred by most ley-hunters at the present time; and that brings us back to dowsing and the overgrounds, for it seems that the overgrounds are the semi-physical or non-physical reality behind leys.

If the overgrounds are the reality behind leys, then it suggests a rather different model and function for the ley-system. The classic Watkins model states that an alignment is a ley if a given number of sites align precisely centre-to-centre within a given distance - typically, four sites within ten miles - with the exception of camps and the larger ‘area’ sites like big stone circles, which leys tend to meet at the tangent rather than centre-to-centre. A true ley will be confirmed by the discovery of minor details like unrecorded mark-stones or aligned gateways, and also by folklore evidence; a chance alignment won’t have this back-up, and will simply feel ‘wrong’.

The model implied by the overgrounds agrees with this classic model in many respects, but takes it further in a number of directions. The first is that both the major and minor sites on a true ley will also coincide with concentrations of Underwood’s patterns, thus apparently using the sites as connection-points between two separate energy-systems, one below and one above the ground. The connection between Underwood’s patterns and the ‘reeling road that rambles round the shire’, to use Chesterton’s phrase, is recognisable even if the cause-effect relationship between them is not; but the connection between the overgrounds and the occasional stretches of ancient straight track aligned on them is anything but clear. Some dowsers have put forward very complicated models to explain it, involving ‘colour-coding’ of the energy in the different overgrounds to mark out sections of track, but I think the simplest and most likely answer is that, as with Underwood’s track-lines, the lines and the roads are where they are because that’s where they felt they ought to be. And I’ll leave you to decide which ‘they’ is the road-makers, and which the tracks themselves…

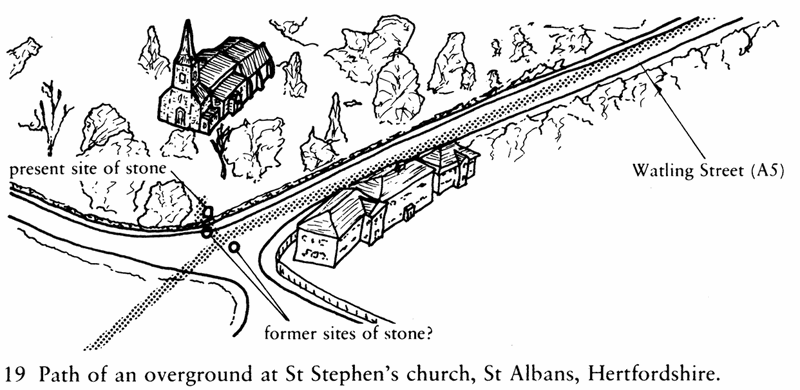

Another difference between the classic model and that implied by the overgrounds is that a ley can still be real and ‘active’ even if one or more of its sites has been moved. The overground doesn’t actually divert from its original straight course, but on reaching the original site of the mark-stone (or whatever) sends out what some dowsers have termed a ‘ray of union’ to connect the stone to the original line. There is an example of one of these in St Stephen’s churchyard in St Albans in Hertfordshire: the three-foot-high mark-stone just inside the churchyard wall, according to Bill Lewis’s and my dowsing results, was originally in the middle of the ancient Watling street, which comes to a crossroads just by the church. The stone was moved at some time from the middle of the road to the footpath, and then again from the footpath into the churchyard, for the overground that runs (unusually) up the middle of the road does an apparent sharp double bend to ‘talk to’ the stone before continuing on its way north. So far the maximum distance found between a moved structure and its original site, where the structure is still ‘talking’ in this way to the original site, is about half a mile.

In the same way there appear to be two-point overgrounds, or two-point leys, depending on how you look at them. Except in the cases of the moved sites I’ve just mentioned, these appear to be deliberate non-alignment so that the energy from some outlying point can be channelled exclusively to one point on the main overground: all of the two-point leys I’ve heard of so far have been connected to a major ley at one end. This doesn’t seem to be the only aspect of non-alignment, for, as we shall see shortly, non-alignment in the sense of deliberate non-connection also seems to be important for a rather different reason.

It’s also important to realise that, as Watkins did in fact imply, centre-to-centre alignment is by no means the only type of alignment, particularly on large and complex sites, or sites that have, like churches and castles, been re-used for other purposes at a later date. Overgrounds, as we saw earlier with Rollright, leave stone circles at any angle between the perpendicular and the tangent; the same seems to be true of camps, though, as Watkins noticed with his leys, tangential alignment seems to be preferred at camps.

It’s more difficult to predict contact-points at re-used sites, since the later use often placed the emphasis elsewhere on the site. At Rudston in Yorkshire, for example, the church-builders couldn’t destroy the twenty-five-foot high Rudstone, so they built their church beside it instead of, as elsewhere, on top of it. At some other sites I’ve been at, the main overground has missed the church completely, and contacted to some uninspiring little hummock on the edge of the churchyard instead. These details are very difficult to pick out in map-work: in practice, whether by dowsing or more conventional ley-hunting, they can only be appreciated in the field.53

The most important aspect of the new model is that it implies that the leys, or overgrounds, or whatever you care to call them, are mainly concerned with present-day energy rather than prehistoric commerce. This came over most clearly when, after I had done my original research on overgrounds and their relationship with leys, I found that others had been that way before me, and were talking of leys as conductors of energies of a number of different types and levels. One dowser who specialised in what might be called a form of environmental medicine told me that she often had to ‘neutralise bad energy down ley-lines’ in order to improve the environmental health of some farm or community. I’m told that one of the Church’s great present-day exorcists started his career at an exorcism of a stone circle, working as assistant to a man who believed that the Russians were using the site as a focus for energies ‘transmitted down ley-lines’, energies which they were using to stir up industrial unrest. This was fifty years ago, when Watkins had only just formulated the concept of leys! Leys, as they say, ain’t quite what they used to be.

If we suggest that the leys or overgrounds carry energies of various types, then since the overgrounds ‘plug into’ Underwood’s patterns at the sites, we can also suggest that Underwood’s patterns are, in much the same way, also carriers or markers of some kind of energy-flow or interaction. As above, so below.

But what, you may ask, is the point or reason for all these energies to be moving about the countryside, assuming that they do exist? For a clue towards an answer we have to move to yet another area of study, Chinese geomancy or Feng-shui, which deals with the practical use of natural energies flowing both below and above the ground, in channels both sinuous and straight.