2. Microservices as seen from the client

A microservice architecture is made of services. Those services handle HTTP communication that request or send data. In case you’re familiar with this, you can head straight to the exercise. Otherwise, let’s review the fundamentals so you can build your knowledge over solid basis.

2.1 HTTP

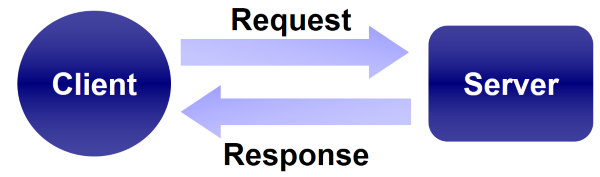

Services, whether they are microservices or not, are usually called over HTTP. Here’s the schema of an HTTP request:

A client sends a request to a server. The client may be a mobile application, an IoT object, a SPA application (Angular, React, …) or whatever you please - including another service. By the way, services will be calling each other in a microservice architecture. The server is what you code, and it contains the business logic.

HTTP in itself is pretty simple. It’s a text-based protocol where the client:

- opens a TCP connection to the server;

- sends data (the request, see below) to the server;

- receives data (the response, see below) from the server;

- closes the connection.

The request is made of two parts: headers and possibly data, separated by a blank line (did I tell you HTTP was simple?). It may look like that:

GET /index HTTP/1.1

Host: www.mysite.com

In the above example there is one single header (Host) and no data. The first line states a verb, a URL, and the version of the HTTP protocol being used. The verb corresponds to what the client wants to do, for instance:

- GET is used to fetch data without modifying server data

- POST is used to update server data

- DELETE is used to - ahem! - delete server data, or at least request deletion.

GET requests do not contain a data payload in the request since the headers and URL are sufficient, but the other types of requests contain data. Here’s an example POST request, but an UPDATE request would look similar:

POST http://server:51426/api/TrainSchedules HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json

Host: server:51426

Content-Length: 94

{"departureTime":"2018-04-03T21:56:48.6711219+01:00","d\

istanceKm":1054,"destination":"Berlin"}

The payload here is JSON, a widely used format for services as we’ll see very soon.

The server processes the request and returns a response using the same TCP connection that was used for the request. That TCP connection is then closed. Here’s an example response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 81

<html>

<body>

<p>Welcome to our site</p>

</body>

</html>

Just like the request, the response is made up of two parts: headers and possibly data, separated by a blank line. Plus a first line that confirms the protocol and provides a status code and message. The status code’s first digit is the most important: 2 means everything was alright, 4 means there was a problem processing the request (you know, that ubiquitous 404 Not found).

There can be many more headers. In the above example you can see the two headers that are commonly used in responses. Content-Type tells the client how the data (what comes below the blank line) should be interpreted. It’s a MIME type. MIME types are well established. Though there are many possible MIME types, only some of them are used for services.

2.2 Payloads

We are focusing on services, right? A (micro)service is mostly used for computer-computer interaction, so it needs a MIME type that’s appropriate for its payloads (the data that is sent in requests and received in responses).

Extensive work from the OASIS consortium in order to standardize services at the beginning of the century (wow, that sounds so vintage) established the XML format for payloads; the consortium even wrapped it into the SOAP standard (which is made of XML). So services used the text/xml MIME type for quite a while, and many still do.

Then came SPA applications (Angular, React and the likes), which became widely used endpoints for user consumption of services. Those applications run in the browser using JavaScript that happens to be slow at XML processing. Sure, JavaScript can parse and produce XML, but it’s a painful process for it. What JavaScript can easily parse and produce is its own format: JSON. Since JSON is as easily read by humans as XML and less verbose, it quickly became the norm for services.

So that’s where we stand today: (micro)services use mainly JSON as their payload format for requests and answers, plus XML sometimes.

2.3 Do you speak JSON

If you aren’t familiar with JSON, don’t worry: it can be learnt very quickly. Think of it as anonymous C# objects. For instance, consider the following declaration:

var myObject = new() {

Foo = "bar",

Value = 5.5,

Really = true

}

This anonymous object instantiation in C# is almost JSON. Let’s replace the equal signs with semicolons, and wrap property names with quotes. This is what we get:

var myObject = new() {

"Foo": "bar",

"Value": 5.5,

"Really": true

}

We’re almost there. We currently have an hybrid C#-JSON code. Now let’s remove the variable declaration and call to new since they don’t describe a value (they describe what we want to do with the value). This is what we get:

{

"Foo": "bar",

"Value": 5.5,

"Really": true

}

Guess what? This is valid JSON. It simply represents the data for an object that has 3 properties.

Now suppose you want to describe an array of object values: all you need to do is use brackets around them. And line returns count as spaces. Yes, all just like C#. Here’s one such array:

[

{ "Foo": "bar", "Value": 5.5, "Really": true },

{ "Foo": "tball", "Value": 2.3, "Really": false }

]

That’s almost all there is to JSON. I could show an example of a complex property value, but that would be just recursive use of the first sample and I’ll spare you that.

2.4 Client types

Once a (micro)service is published and listens over HTTP (that’s what we’ll do in this book), many different types of clients can consume it:

- heavy clients like UWP, WPF, Windows Forms;

- browsers using SPA applications like Angular, React, Vue.js, Knockout or jQuery, or even plain JavaScript

- mobile applications;

- IoT devices, e.g. your fridge ordering milk when it senses you’ll soon be running out of milk;

- other services, which makes for a services-based architecture;

- utilities like command-line applications.

In this book you’ll use WPF, command-line and services as the clients of your services.

2.5 Manual testing

Once you start building a microservice, you’ll want to test it. A microservice usually has no user interface, hence testing requires you to send HTTP requests and check for the response.

An obvious tool is your browser. When you type a URL in the address bar, your browser issues an HTTP GET request to that URL. Downside: you have no control over the headers it sends. Which means that you really need another tool.

Good news: there are many tools out there that will enable you to issue HTTP requests like Fiddler or Postman. You can go on and use any tool you like really; for simplicity sake in this book we’ll use the Invoke-WebRequest command that is part of PowerShell since it’s already present on your Windows machine. If you’re using a Linux-based machine, you can use the curl command. Even PowerShell accepts the curl command (and maps it to its Invoke-WebRequest command).

Suppose you want to make the following HTTP request: GET http://someserver/api

You could issue the following PowerShell command:

Invoke-WebRequest http://someserver/api

This is the actual HTTP request that gets issued:

GET http://someserver/api HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT; Windows NT 10.0; f\

r-FR) WindowsPowerShell/5.1.16299.98

Host: someserver

Proxy-Connection: Keep-Alive

You aren’t required to provide other parameters since GET is the default HTTP verb used by the Invoke-WebRequest command. The response is provided in full details, but if you are interested only in the data payload, you may get the Content property from the result:

(Invoke-WebRequest http://someserver/api).Content

When you need to use a verb other than GET you’ll surely need to send data. The Invoke-WebRequest command allows you to provide your data using the Body parameter and the verb to be used is passed through the Method parameter.

Invoke-WebRequest -Method POST -Body '{"foo":"bar","val\

ue":10}' -Header @{"Content-Type"="application/json"} h\

ttp://someserver/api

Note that in the command above we’re also sending a Content-Type header in order to tell the server that we’re using JSON as the payload data format - this depends on the specific API you call.

This is the actual HTTP request that gets issued when the command above is executed:

POST http://someserver/api HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT; Windows NT 10.0; f\

r-FR) WindowsPowerShell/5.1.16299.98

Host: someserver

Content-Length: 24

{"foo":"bar","value":10}

Let’s try this on a real-world example.

2.6 Exercise - Invoke a microservice manually

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/api.php?action=query&format=\

json&prop=info&list=allpages

2.7 Exercise solution

- From a PowerShell command-line, type the following and check the returned Content:

Invoke-WebRequest "https://en.wikipedia.org/w/api.php?a\

ction=query&format=json&prop=info&list=allpages"

- Make sure the HTTP response status code is 200 OK.