Understanding fonts

Most documents are based on text. To create documents you have to understand how fonts work and how to use them properly. Typography is an art itself and I’m sure you love nicely printed books and brochures. Would be nice if you could make such things too, right?

I’ve engineered dynamic documents used by thousands of teachers, students, parents, customers and so on. I had to adhere to the highest standards possible because those documents communicated very important things: grades, prices, business deals, formalities. The mere text on paper impacted people’s lives.

I learned about serif and sans-serif typefaces, about varying the space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful. Historical. Artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture. And I found it fascinating.

–Steve Jobs

How fonts work?

To build a piece of text you need characters that will make letters and words. Before we start, there are some terms you should familiarize with.

A character set defines mappings between numeric codes and characters: letters, digits, symbols, and so on. For example, in the ASCII table, the decimal number 65 represents a Latin letter A. This is an abstract representation; we still don’t know how this letter should be drawn on screen or printed.

An encoding specifies how the character codes will be represented as bytes. For ANSI this is simple: a byte value 65 (decimal) is equal to ASCII code 65, which represents capital letter A. However, if a character set exceeds 256 possible values of a single byte, we dive into the world of multi-byte encodings. The most popular ones are UTF-8, UTF-16, UTF-32, UCS-2 and UCS-4 for the Unicode standard.

There are hundreds of thousands of characters in the world, including many alphabets, scripts, and even emojis. Until 1990s, computers used different sets of 256 characters, enough to fit in one byte. This reduced the ability to interchange documents; the same byte sent from an English to a Russian computer would be represented as a different character. The Unicode standard was made as an effort to collect all the characters in the world in one set.

Although Unicode has been used for years now, you still need to tell the conversion tool that you’re using Unicode, preferably with the <meta charset="utf-8"> tag we mentioned in chapter 4. Some tools might still default to old encodings like ISO-8859-1.

A font is a set of glyphs - readable characters and other symbols that represent a character set. A font data file contains either bitmaps or vectors that make up all the character shapes.

Typesetting is a broad topic. To please the aesthetic feelings of readers, font systems have to provide many features. For example, it’s common to use ligatures: symbols that represent pairs of letters like ff and fi. Font files can also provide hinting to optimize character rendering on computer screens, especially at small font sizes. Another feature is kerning which defines spacing between pairs of letters, like “V” and “A”, to maintain good visual proportions.

Having these basics described, we can start using fonts and typing text the way we want to!

Font file formats in the PDF

A PDF file defines which fonts are used in certain parts of the document. To draw a page properly, these fonts have to be either installed in the operating system, built into the PDF reader or provided along with the document.

The most common font file formats are OpenType, TrueType and Type 1. They differ in features and the way of describing shapes. All of them can be used in a PDF document, but it is a font interpreter’s job to understand a font file format.

Fonts designed during different times, by designers having their own preferences and capabilities, would use different formats. It may be impossible to convert between font file formats without data loss.

Document generators often embed a font subset in a document. It’s not necessary to attach the whole font file that includes thousands of glyphs. A program chooses only a subset that is enough to represent the document contents.

If a font is not provided by the document, it can be substituted by a reader to one of the standard Type 1 fonts, including Times-Roman, Helvetica, Courier and Symbol. You can also explicitly refer to these standard fonts in a document, just like we did in the chapter 3. However, these aren’t Unicode fonts. If you don’t make sure a Unicode font is embedded in a document, some text contents might be lost on an end user’s machine.

Picking a proper font

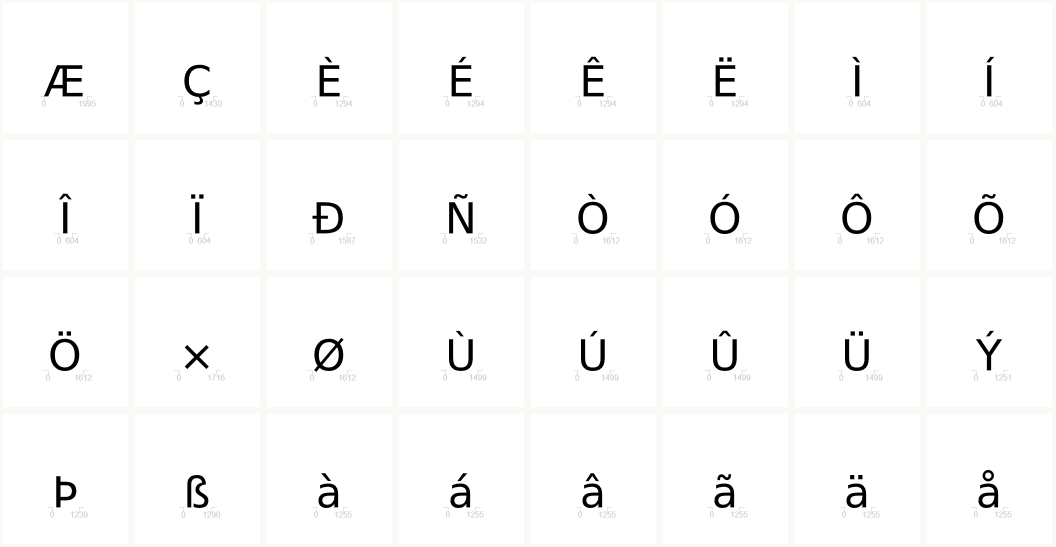

To use a custom font, first you have to choose one that covers all characters you need in your document or its part. This should be common sense, but sometimes we (or the client) forgets about it.

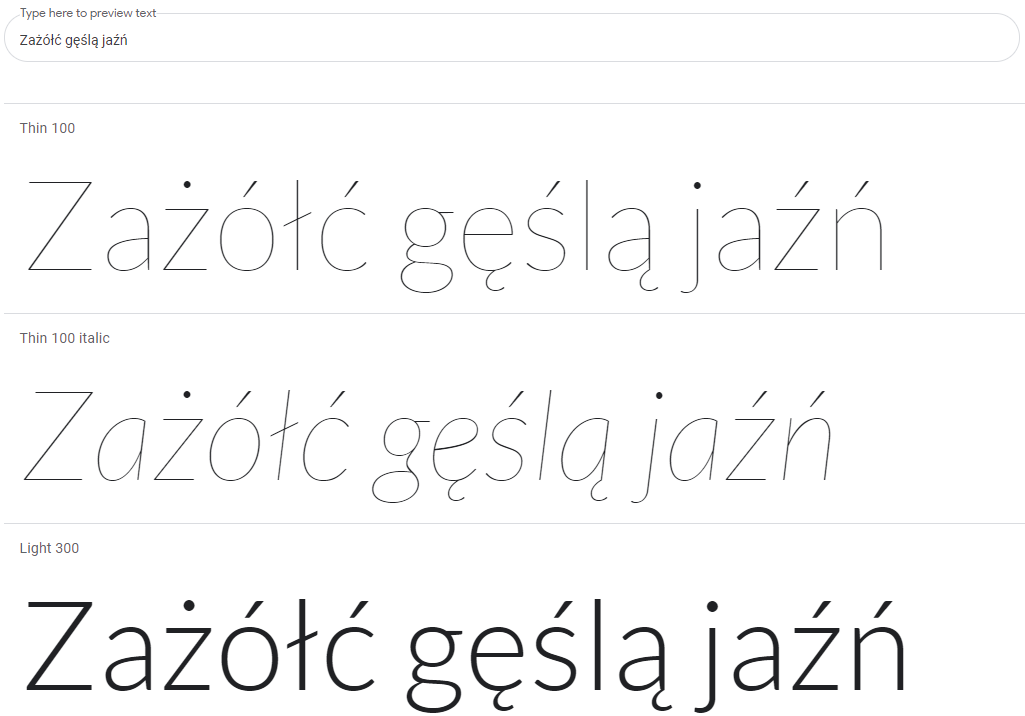

For example if you pick a fancy header font and your language includes non-Latin characters, check if the font contains glyphs for them! Either use a website that allows testing fonts or download the font files and try them in some text editor or graphics program.

Also remember that even if you use English, you might have users from other countries. They won’t like seeing their names misspelled. For example, Mr. Lech Wałęsa1 would be disappointed to see his name printed as Lech Wa??sa or Lech Walesa.

As you can see in the example above, one font family can have mutiple styles and weights. The shapes for “light” and “bold” or “normal” and “italic” are different. A font is not automatically converted from one version to another; it is up to the font designer to provide proper files that comply to the designer’s vision.

Usually, there are no “one-size-fits-all” solutions. Some fonts do not have an “italic” or “bold italic” versions on purpose. Some fonts contain only uppercase letters (capitals). Other fonts, like fancy handwriting-like ones, are not readable in small sizes. One font can be designed explicitly for small text and another can be dedicated for big titles. Moreover, what looks good on a screen might not be aesthetically pleasing on paper.

Selecting a font in CSS

Let’s remind ourselves how to pick a font in CSS. The most basic syntax looks like this:

1 body {

2 font-family: Verdana, Arial, sans-serif;

3 }

The example above means that we prefer the Verdana font, but in case if it’s not available we recommend substituting it either with Arial or any sans-serif font. We depend only on fonts available in a certain system. Every OS has a basic set of fonts, but you can also install your own.

You might want to use a font from the web in your document without installing it globally in the operating system. In the example below, we import a font file and assign a local name Lato. We declare this is a normal (not italic) font of a regular weight:

1 @font-face {

2 font-family: 'Lato';

3 font-style: normal;

4 font-weight: normal;

5 src: url('https://example.org/lato.ttf') format('truetype');

6 }

7

8 body {

9 font-family: Lato;

10 }

The @font-face syntax works fine with any Chromium-based tools, and also WeasyPrint and Prince. Other tools make selecting a font a bit harder.

Providing a font to wkhtmltopdf

For security reasons, wkhtmltopdf blocks any access to remote font files. It cannot even read a font file from a local drive.

To pick a custom font, we will use a data URL trick. First we have to encode the font file with Base642. We can use either the PHP function base64_encode(), the Linux console command base64 or any Base64 encoder available online.

Then we copy the encoded file contents and paste into the CSS:

1 @font-face {

2 font-family: 'CaslonItalic';

3 src: url(data:font/truetype;charset=utf-8;base64,PASTE_IT_HERE) format("truetype");

4 }

5

6 body {

7 font-family: CaslonItalic;

8 }

Because an encoded font file can be very long, it’s more convenient to move the @font-face declaration to a separate CSS file and then use @include to attach it to the main stylesheet. You can decide if you want to include that encoded file in your repository, or generate it on-demand in some build script.

Providing a font to Dompdf

The Dompdf PHP library has its internal font metrics engine which incorporates local caching. The mechanism is cumbersome because you have to manually register the font before using it.

This can be done with a load_font.php script which is available in the dompdf/utils package. Since it would require to copy another repo to the vendor/dompdf/dompdf directory, I don’t really like this method.

Another way is to extend your PDF rendering code. During the first round, Dompdf will create cache files in the vendor/dompdf/dompdf/lib/fonts directory - which means your script must have write access there. Next time, those cached resources will be used to embed the font in a PDF:

1 use Dompdf\Dompdf;

2 use Dompdf\Options;

3

4 $fontDirectory = '/home/someuser/fonts';

5

6 $options = new Options();

7 $options->setChroot($fontDirectory);

8

9 $pdf = new Dompdf($options);

10 $pdf->getFontMetrics()->registerFont(

11 ['family' => 'CaslonItalic', 'style' => 'italic', 'weight' => 'normal'],

12 $fontDirectory . '/CaslonItalic.ttf'

13 );

14 $pdf->loadHtml($html);

15 $pdf->render();

16 file_put_contents('output.pdf', $pdf->output());

The setChroot() call is necessary for security purposes, so that Dompdf won’t access any system files.

Note that when adding a font file you must specify its corresponding style and weight.

Setting a custom font in mPDF

mPDF has a decent documentation which explains a lot of nuances related to international font handling.

To use your own font you have to register it. There is one major drawback: you have to invent a font family name that’s all lowercase and without any spaces nor other special characters. So instead of font-family: 'DejaVu Sans' you have to enter font-family: dejavusans.

You can register as many font directories as you need. Moreover, you’ll need a temporary directory to store font cache. By default it’s vendor/mpdf/mpdf/tmp/mpdf/ttfontdata and the script must have write permissions for that. Fortunately you can set another cache path:

1 use Mpdf\Config\ConfigVariables;

2 use Mpdf\Config\FontVariables;

3 use Mpdf\Mpdf;

4

5 $fontDirectory = '/home/someuser/fonts';

6

7 $defaultConfig = (new ConfigVariables())->getDefaults();

8 $fontDirs = $defaultConfig['fontDir'];

9

10 $defaultFontConfig = (new FontVariables())->getDefaults();

11 $fontData = $defaultFontConfig['fontdata'];

12

13 $mpdf = new Mpdf([

14 'fontDir' => \array_merge($fontDirs, [

15 $fontDirectory,

16 ]),

17 'fontdata' => $fontData + [

18 'caslon' => [

19 'I' => 'CaslonItalic.ttf',

20 ],

21 ],

22 'tempDir' => $fontDirectory . '/tmp',

23 ]);

24 $mpdf->WriteHTML($html);

25 $mpdf->Output('output.pdf', 'F');

When registering font files, you have to declare their style with R, B, I and BI identifiers, corresponding to “regular”, “bold”, “italic” and “bold italic” styles, respectively.

Custom fonts in TCPDF

TCPDF follows a similar font registration pattern to the previous two libraries. You can do it in two ways - either in the command line, or directly in PHP code.

Thanks to the command line you can embed the conversion commands in some Continuous Delivery pipeline that builds your application. Instead of committing the temporary font files, you can rebuild them every time with a simple command like this (assuming you’re using Composer):

1 php ./vendor/tecnickcom/tcpdf/tools/tcpdf_addfont.php -b -f 32 -o /home/someuser/fon\

2 ts/tmp/ -i CaslonItalic.ttf

If you don’t use the command line, you can still do the same conversion thing in PHP using the TCPDF_FONTS class:

1 $fontDirectory = '/home/someuser/fonts/';

2

3 // The trailing slash is mandatory here

4 $tempDirectory = $fontDirectory . 'tmp/';

5

6 $fontname = TCPDF_FONTS::addTTFfont($fontDirectory . 'CaslonItalic.ttf', 'TrueTypeUn\

7 icode', '', 32, $tempDirectory);

8

9 $pdf = new TCPDF('P', 'mm', 'LETTER');

10 $pdf->AddPage();

11 $pdf->AddFont($fontname, 'I', $tempDirectory . $fontname . '.php');

12 $pdf->writeHTML($html);

13 file_put_contents('output.pdf', $pdf->Output('', 'S'));

The addTTFfont() method parses the original font file and creates three temporary files in the directory of your choice. Obviously, the script must have write access to that path. The return value holds a font file name which is usually a lowercase string. With AddFont() method you register the PHP font definition file created earlier.

Now you can use the font inside the document like this (remember about the lowercase font family name):

1 body {

2 font-family: 'caslon';

3 font-size: 72pt;

4 font-style: italic;

5 }

Instead of using CSS, you can also set the current font with PHP:

1 $pdf->SetFont($fontname, 'I', 72);

The mysterious number 32 which appears both in the command line call and the addTTFfont() method is the font descriptor flag from the PDF specification. Fixed and italic fonts are usually autodetected, but for other types you have to specify an exact flag value:

| Font descriptor flag | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 1 | fixed font |

| 4 | symbol font |

| 8 | script (handwriting) |

| 32 | non-symbol (standard) font |

| 64 | italic font |

| 65,536 | all caps (no lowercase letters) |

| 131,072 | small caps |

Text transformations

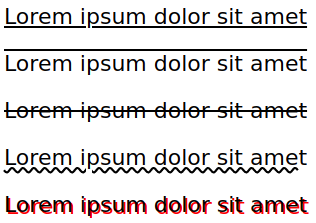

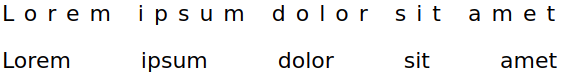

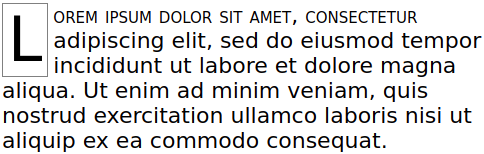

Although some transformations like italics or bold cannot be done automatically, there are plenty of other operations we can perform on text. We’ll see what is possible through CSS:

Below there is a CSS code for the example above:

1 p {

2 width: 500px;

3 }

4

5 p::first-line {

6 font-variant: small-caps;

7 }

8

9 p::first-letter {

10 border: solid gray 1px;

11 float: left;

12 font-size: 2.8em;

13 margin-right: 5px;

14 padding: 0 5px;

15 }

Note that the HTML to PDF converters might not interpret all these CSS rules properly.

You can find more examples of styling text with CSS on the Mozilla Developer’s Network and on the CSS-Tricks site.

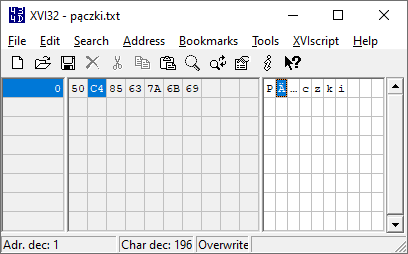

ANSI or Mac versus Unicode

If you create a standard plain text file in Notepad, it is going to use a single-byte ANSI encoding (Windows) or a Mac OS Roman encoding (classic Mac OS). If you only use Latin characters, you will be fine - but the problems arise with languages that contain letters outside the Latin alphabet.

Because it is impossible to squeeze all the world’s alphabets into a set of one-byte values, operating systems introduced multiple code pages (or charsets) based on the language setting. The same code in a different code page will represent a different character. The default page on Windows for English is CP-1252 (similar to ISO-8859-1), but for Polish there is a separate page called CP-1250 with different characters in it. Some old Polish websites were encoded in the ISO-8859-2 standard which is again different from all previous ones. Madness!

This is why Unicode was invented in the early 1990s, but it took many years to adopt it widely. Today all modern websites use Unicode and the most popular encoding is UTF-8. Characters are organized into planes and blocks. In UTF-8, the basic ASCII set is still encoded using single bytes, while codes above 255 are represented with two to four bytes.

In an HTML document, the best way to ensure that the UTF-8 encoding will be understood is to add the <meta> tag:

1 <html>

2 <head>

3 <meta charset="utf-8">

4 </head>

5 <body>

6 <p>Zażółć gęślą jaźń!</p>

7 </body>

8 </html>

Summary

In this chapter you have learned the difference between character set, encoding and a font. You know how to pick a font and use it in an HTML document which might be later converted to PDF. You know how to ensure proper encoding of characters from different languages.

You’ve also learned that some conversion tools may have limited font reading capabilities. Instead of simple @font-face syntax, they expect additional scripting work to register font files.