Linux Concepts

What is Linux?

In it’s simplest form, the answer to the question “What is Linux?” is that it’s a computer operating system. As such it is the software that forms a base that allows applications that run on that operating system to run.

In the strictest way of speaking, the term ‘Linux’ refers to the Linux kernel. That is to say the central core of the operating system, but the term is often used to describe the set of programs, tools, and services that are bundled together with the Linux kernel to provide a fully functional operating system.

An operating system is software that manages computer hardware and software resources for computer applications. For example Microsoft Windows could be the operating system that will allow the browser application Firefox to run on our desktop computer.

Linux is a computer operating system that is can be distributed as free and open-source software. The defining component of Linux is the Linux kernel, an operating system kernel first released on 5 October 1991 by Linus Torvalds.

Linux was originally developed as a free operating system for Intel x86-based personal computers. It has since been made available to a huge range of computer hardware platforms and is a leading operating system on servers, mainframe computers and supercomputers. Linux also runs on embedded systems, which are devices whose operating system is typically built into the firmware and is highly tailored to the system; this includes mobile phones, tablet computers, network routers, facility automation controls, televisions and video game consoles. Android, the most widely used operating system for tablets and smart-phones, is built on top of the Linux kernel.

The development of Linux is one of the most prominent examples of free and open-source software collaboration. Typically, Linux is packaged in a form known as a Linux distribution, for both desktop and server use. Popular mainstream Linux distributions include Debian, Ubuntu and the commercial Red Hat Enterprise Linux. Linux distributions include the Linux kernel, supporting utilities and libraries and usually a large amount of application software to carry out the distribution’s intended use.

A distribution intended to run as a server may omit all graphical desktop environments from the standard install, and instead include other software to set up and operate a solution stack such as LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL and PHP). Because Linux is freely re-distributable, anyone may create a distribution for any intended use.

Linux is not an operating system that people will typically use on their desktop computers at home and as such, regular computer users can find the barrier to entry for using Linux high. This is made easier through the use of Graphical User Interfaces that are included with many Linux distributions, but these graphical overlays are something of a shim to the underlying workings of the computer. There is a greater degree of control and flexibility to be gained by working with Linux at what is called the ‘Command Line’ (or CLI), and the booming field of educational computer elements such as the Raspberry Pi have provided access to a new world of learning opportunities at this more fundamental level.

Executing Commands in Linux

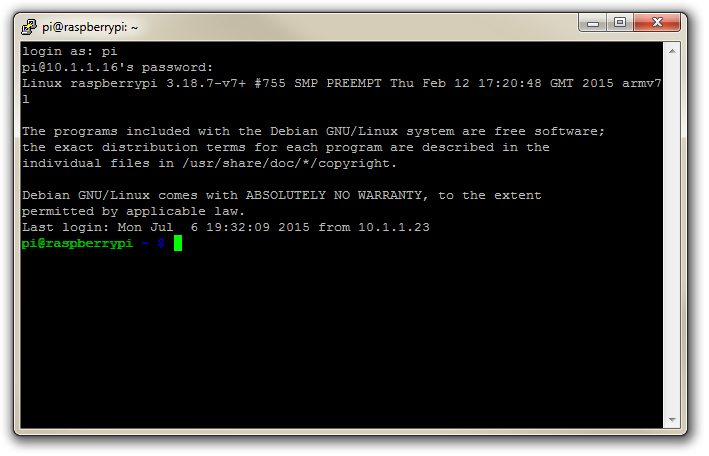

A command is an instruction given by a user telling the computer to carry out an action. This could be to run a single program or a group of linked programs. Commands are typically initiated by typing them in at the command line (in a terminal) and then pressing the ENTER key, which passes them to the shell.

A terminal refers to a wrapper program which runs a shell. This used to mean a physical device consisting of little more than a monitor and keyboard. As Unix/Linux systems advanced the terminal concept was abstracted into software. Now we have programs such as LXTerminal (on the Raspberry Pi) which will launch a window in a Graphical User Interface (GUI) which will run a shell into which you can enter commands. Alternatively we can dispense with the GUI all together and simply start at the command line when we boot up.

The shell is a program which actually processes commands and returns output. Every Linux operating system has at least one shell, and most have several. The default shell on most Linux systems is bash.

The Command

Commands on Linux operating systems are either built-in or external commands. Built-in commands are part of the shell. External commands are either executables (programs written in a programming language and then compiled into an executable binary) or shell scripts.

A command consists of a command name usually followed by one or more sequences of characters that include options and/or arguments. Each of these strings is separated by white space. The general syntax for commands is;

commandname [options] [arguments]

The square brackets indicate that the enclosed items are optional. Commands typically have a few options and utilise arguments. However, there are some commands that do not accept arguments, and a few with no options.

As an example we can run the ls command with no options or arguments as follows;

The ls command will list the contents of a directory and in this case the command and the output would be expected to look something like the following;

Options

An option (also referred to as a switch or a flag) is a single-letter code, or sometimes a single word or set of words, that modifies the behaviour of a command. When multiple single-letter options are used, all the letters are placed adjacent to each other (not separated by spaces) and can be in any order. The set of options must usually be preceded by a single hyphen, again with no intervening space.

So again using ls if we introduce the option -l we can show the total files in the directory and subdirectories, the names of the files in the current directory, their permissions, the number of subdirectories in directories listed, the size of the file, and the date of last modification.

The command we execute therefore looks like this;

And so the command (with the -l option) and the output would look like the following;

2 pi pi 4096 Feb 20 08:07 Desktop

drwxrwxr-x 2 pi pi 4096 Jan 27 08:34 python_games

Here we can see quite a radical change in the formatting and content of the returned information.

Arguments

An argument (also called a command line argument) is a file name or other data that is provided to a command in order for the command to use it as an input.

Using ls again we can specify that we wish to list the contents of the python_games directory (which we could see when we ran ls) by using the name of the directory as the argument as follows;

The command (with the python_games argument) and the output would look like the following (actually I removed quite a few files to make it a bit more readable);

Putting it all together

And as our final example we can combine our command (ls) with both an option (-l) and an argument (python_games) as follows;

Hopefully by this stage, the output shouldn’t come as too much surprise, although again I have pruned some of the files for readabilities sake;

1 pi pi 9731 Jan 27 08:34 4row_arrow.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 7463 Jan 27 08:34 4row_black.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 8666 Jan 27 08:34 4row_board.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 18933 Jan 27 08:34 4row_computerwinner.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 25412 Jan 27 08:34 4row_humanwinner.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 8562 Jan 27 08:34 4row_red.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 14661 Jan 27 08:34 tetrisc.mid

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 15759 Jan 27 08:34 tetrominoforidiots.py

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 18679 Jan 27 08:34 tetromino.py

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 9771 Jan 27 08:34 Tree_Short.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 11546 Jan 27 08:34 Tree_Tall.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 10378 Jan 27 08:34 Tree_Ugly.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 8443 Jan 27 08:34 Wall_Block_Tall.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 6011 Jan 27 08:34 Wood_Block_Tall.png

-rw-rw-r-- 1 pi pi 8118 Jan 27 08:34 wormy.py

Commands

Wildcards

An important concept to grasp in Linux is that of using wildcards. In a sporting context a wildcard is something (or someone) that can be introduced to a game as a substitute. It may not have a strictly defined value, but could fill in for a range of standard objects.

Wildcards are a feature on the Linux command line (and other places) that makes the command line far more versatile than graphical file managers. Anyone who’s tried to use fancy combinations of shift / ctrl and mouse clicking while sorting in a file manager will attest to a degree of difficulty.

For example, if we have a directory with a large number files and subdirectories, and we need to move all the Python (files ending in .py) files, that have the word ‘pi’ somewhere in their names, from that large directory into another directory. This has the potential to be a time consuming task.

At the Linux command line that task is almost as easy to carry out as moving only one Python file, and it’s simple because of the wildcards. These are special characters that allow us to select file names that match certain patterns of characters. This helps us select a range of matching of files by typing just a few characters, and in most cases (IMHO) it’s easier than using a graphical file manager.

Here’s a list of the most commonly used wildcards :

As well as being able to be applied in isolation, some of the real strengths of wildcards comes when using them in combination.

Examples

Zero or more characters

To list all Python files with ‘pi’ in their names;

Exactly one character

To list all files in the current directory with three character file extensions;

Exactly one of the characters listed

To list all files that have an extension that begins with ‘p’ or ‘j’;

Exactly one character in the range specified

To list all files that have a number in the file name;

Combination

To list all files that start with one of the three first or three last letters of the alphabet and end with an extension ‘jpg’ or ‘png’.

Regular Expressions

Regular expressions (also called ‘regex’) are a pattern matching system that uses sequences of characters constructed according to pre-defined syntax rules to find desired strings in text. The topic of regular expressions is a book in itself and I heartily recommend further reading for those who find the need to use them in anger.

The command grep (where the re in grep stands for regular expression) is an essential tool for any one using Linux, allowing regular expressions to be used in file searches or command outputs. Although the use of regular expressions is widespread in multiple facets of computing operations.

For example, if we wanted to search the file dmesg which is in the /var/log directory and wanted to show each line that contained the string of characters CPU. we would use the grep command as follows;

The output from the command will appear similar to the following;

This is a basic example that utilises a simple string to match on and shouldn’t necessarily be regarded as a great use of regular expressions. However, if we wanted to limit the returned results to instances where the string was the text CPU followed by the number 0, 1, 2 or 3, we could use a regular expression with a facility that included a range of options. This is accomplished by using the square brackets [] with the specified range inside.

In our case we want the text CPU and it must be immediately followed by a number in the range 0 to 3. This can be designated by the regular expression CPU[0-3].

Which means that our search as follows;

… will result in;

The square brackets are ‘metacharacters’ and it is the use of these metacharacters that provide regular expressions with the foundation of their strength.

The following are some of the most commonly used metacharacters and a very short description of their effect (we will show examples further on);

[ ] |

Match anything inside the square brackets for ONE character |

^ |

(circumflex or caret) Matches only at the beginning of the target string (when not used inside square brackets (where it has a different meaning)) |

$ |

Matches only at the end of the target string |

. |

(period or full-stop) Matches any single character |

? |

Matches when the preceding character occurs 0 or 1 times only |

* |

Matches when the preceding character occurs 0 or more times |

+ |

Matches when the preceding character occurs 1 or more times |

( ) |

Can be used to group parts of our search expression together |

| |

(vertical bar or pipe) Allows us to find the left hand or right values |

Match a defined single character with square brackets ([])

As demonstrated at the start of this section, the use of square brackets will allow us to match any single character. The example we used below employed the use of the dash (or minus) character as a range signifier to signify that the possible characters were 0, 1, 2, or 3.

We could also have simply put each character in the square brackets as follows;

In either case it should be noted that only a single character is matched for the entries in the square brackets.

We can specify more than one range and we can also distinguish between upper case and lower case characters. Therefore the following ranges will have the corresponding results;

-

[a-z]: Match any single character between a to z. -

[A-Z]: Match any single character between A to Z. -

[0-9]: Match any single character between 0 to 9. -

[a-zA-Z0-9]: Match any single character either a to z or A to Z or 0 to 9

Within square brackets we can also use the circumflex or caret character (^) to negate the characters selection. I.e. with a caret we can say search for lines with the text CPU and it must be immediately followed by a character that is not in the range 0 to 3. This is done as follows;

Which would result in an output similar to the following;

Note that none of the previous lines with CPU0, CPU1, CPU2 or CPU3 have been listed.

Match at the beginning of a string (^)

We can use the circumflex or caret character (^) to match lines of text that begin with a specific set of characters.

Given a text file names foo.txt with the following contents;

If we run the grep command looking for the string ‘Second’ as follows;

We should have two lines returned as below;

But if we use the caret character to designate that we are only looking for lines that start with our string as follows;

… we will get the following output where only the second line is returned;

Match at the end of a string ($)

We can use the dollar sign character ($) to match lines of text that finish with a specific character or set of characters.

For example, given a text file names foo.txt with the following contents;

If we use the dollar sign character to search for all lines that end in ‘ing’ as follows;

… we will get the following output where only the second line is returned;

Match any single character (.)

The . (period) character will allow us to match any single character in this position.

For example, given a text file names foo.txt with the following contents;

… if we wanted to return all lines where the characters ing were in the middle of the line (not at the end) we could run the following grep command;

This would produce an output similar to the following;

While there are two other lines with ing in them, (the first and third lines), both of them end with ‘ing’ and as a result there is no character after them. The only one where there is ‘ing’ with a character following it is in the second line.

Match when the preceding character occurs 0 or 1 times only (?)

It may be difficult to think of a situation where we would want to match against something that occurs 0 or 1 time, but the best example comes from the world of language. In American spelling the word ‘color’ differs from the British spelling by the omission of the letter ‘u’ (‘colour’). We can write a regular expression that will match either spelling as follows;

This way the question mark denotes that for a match to occur, the preceding character must either not be present or must occur once. The additional characters (‘colo’ and the ‘r’) are literals in the sense that they must be present exactly as stated. The only variable in the expression is the ‘u’.

Match when the preceding character occurs 0 or more times (*)

The asterisk metacharacter in regular expressions can be one of the most confusing options to use, but this is mainly because its real strength is applied when matched with other metacharacters.

For example it could be argued that a regular expression such as q*w will match w, qw and qqqw, however if we use a period and an asterisk together (.*) we gain a function that will match zero or more of any series of characters.

In this case we can use a regular expression such as …

… to find any combination of characters that start with pa and end with y and have any number of characters (including none) in between. These would include the following;

Match when the preceding character occurs 1 or more times (+)

The use of the + character to allow one or more instances of a character is similar to that of the asterisk. Where the * metacharacter might return the following matches from the regular expression fe*d;

The use of fe+d would result in;

Group parts of a search expression together (())

Regular expressions can be combined into subgroups that can be operated on as separate entities by enclosing those entities in parenthesis. For example, if we wanted to return a match if we saw the word ‘monkey’ or ‘banana’ we would use the or metacharacter | (the pipe) to try to match one string or another as follows;

Find one group of values or another (|)

The pipe metacharacter allows us to apply a logical ‘or’ operator to our pattern matching. For example if we wanted to return a match if we saw the word ‘monkey’ or ‘banana’ we would use the words encapsulated in parenthesis and the pipe metacharacter to try to match one string or another as follows;

Extended Regular Expressions

In basic regular expressions the meta-characters ?, +, {, |, (, and ) are not regarded as special and instead we need to use the backslashed versions \?, \+, \{, \|, \(, and \).

Pipes (|)

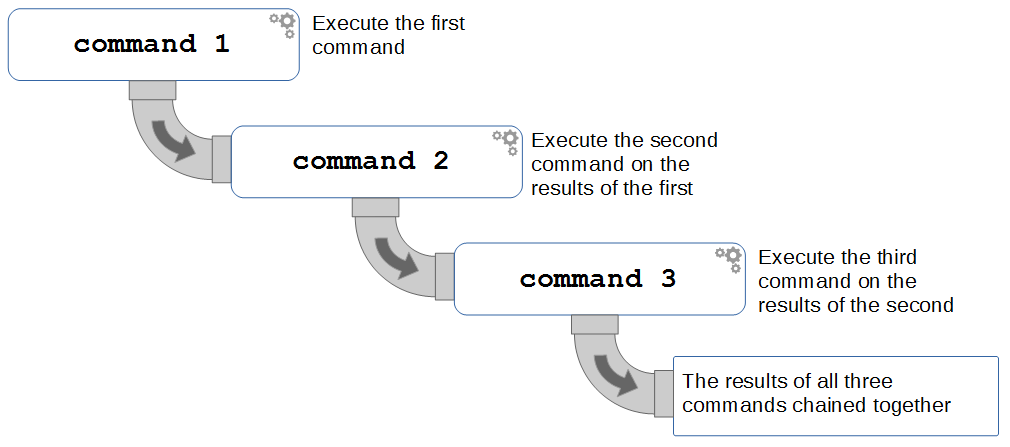

Pipes are used in Linux to combine commands to allow them to have the output from a command feed directly into another command and so on. The idea is to use multiple commands to create a sequence of processing information from one command to another.

The commands are separated by the vertical line (|) that is normally found above the backslash key (\). This is the character that denotes the ‘pipe’ function. to combine three functions together with pipe symbol we would have something like the following;

As the name suggests, we can think of the pipe function as representing commands linked by a pipe where the command runs a function that is output in a pipe to flow to the second command and on to the eventual final output. To help with the visual association it might be useful to think of the connections similar to the following;

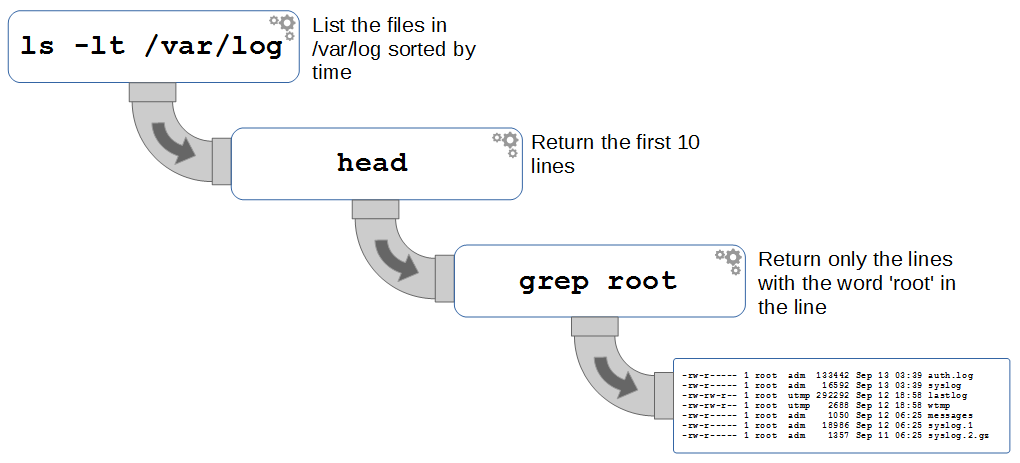

To demonstrate by example we can consider a set of commands lined as follows;

Here we have the ls command that is listing the contents of the /var/log directory with the listings sorted by time. This is then feeding into the head command that will only display the first 10 of those lines. We then feed those 10 lines into a grep command that filters the result to show only those lines that have the word ‘root’ in them.

The command as it would be run from the command line would be as follows;

… and the output would appear something like the following;

Linux Directory Structure

To a new user of Linux, the file structure may feel like something at best arcane and in some cases arbitrary. Of course this isn’t entirely the case and in spite of some distribution specific differences, there is a fairly well laid out hierarchy of directories and files with a good reason for being where they are.

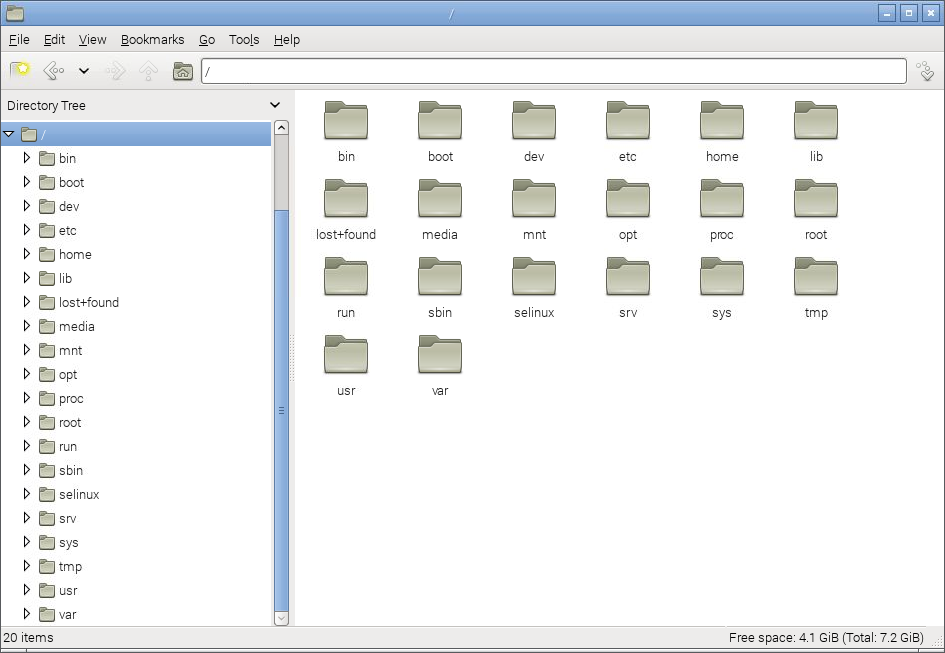

We are frequently comfortable with the concept of navigating this structure using a graphical interface similar to that shown below, but to operate effectively at the command line we need to have a working knowledge of what goes where.

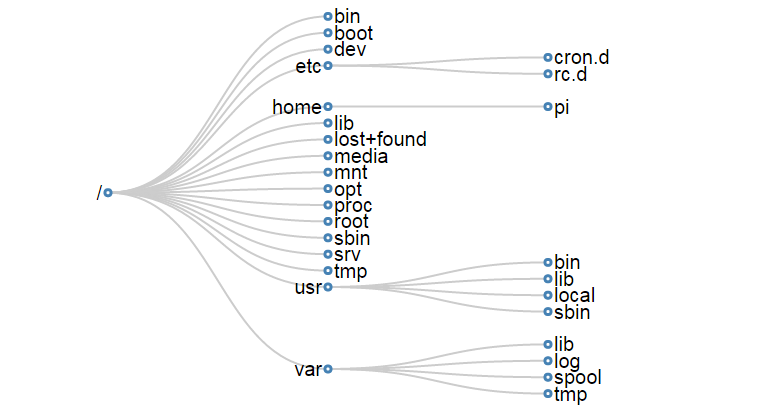

The directories we are going to describe form a hierarchy similar to the following;

For a concise description of the directory functions check out the cheat sheet. Alternatively their function and descriptions are as follows;

/

The / or ‘root’ directory contains all other files and directories. It is important to note that this is not the root users home directory (although it used to be many years ago). The root user’s home directory is /root. Only the root user has write privileges for this directory.

/bin

The /bin directory contains common essential binary executables / commands for use by all users. For example: the commands cd, cp, ls, ping, ps. These are commands that may be used by both the system administrator and by users, but which are required when no other filesystems are mounted.

/boot

The /boot directory contains the files needed to successfully start the computer during the boot process. As such the /boot directory contains information that is accessed before the Linux kernel begins running the programs and process that allow the operating system to function.

/dev

The /dev directory holds device files that represent physical devices attached to the computer such as hard drives, sound devices and communication ports as well as ‘logical’ devices such as a random number generator and /dev/null which will essentially discard any information sent to it. This directory holds a range of files that strongly reinforces the Linux precept that Everything is a file.

/etc

The /etc directory contains configuration files that control the operation of programs. It also contains scripts used to startup and shutdown individual programs.

/etc/cron.d

The /etc/cron.d, /etc/cron.hourly, /etc/cron.daily, /etc/cron.weekly, /etc/cron.monthly directories contain scripts which are executed on a regular schedule by the crontab process.

/etc/rc?.d

The /rc0.d, /rc1.d, /rc2.d, /rc3.d, /rc4.d, /rc5.d, /rc6.d, /rcS.d directories contain the files required to control system services and configure the mode of operation (runlevel) for the computer.

/home

Because Linux is an operating system that is a ‘multi-user’ environment, each user requires a space to store information specific to them. This is done via the /home directory. For example, the user ‘pi’ would have /home/pi as their home directory.

/lib

The /lib directory contains shared library files that supports the executable files located under /bin and /sbin. It also holds the kernel modules (drivers) responsible for giving Linux a great deal of versatility to add or remove functionality as needs dictate.

/lost+found

The /lost+found directory will contain potentially recoverable data that might be produced if the file system undergoes an improper shut-down due to a crash or power failure. The data recovered is unlikely to be complete or undamaged, but in some circumstances it may hold useful information or pointers to the reason for the improper shut-down.

/media

The /media directory is used as a directory to temporarily mount removable devices (for example, /media/cdrom or /media/cdrecorder). This is a relatively new development for Linux and comes as a result of a degree of historical confusion over where was best to mount these types of devices (/cdrom, /mnt or /mnt/cdrom for example).

/mnt

The /mnt directory is used as a generic mount point for filesystems or devices. Recent use of the directory is directing it towards it being used as a temporary mount point for system administrators, but there is a degree of historical variation that has resulted in different distributions doing things different ways (for example, Debian allocates /floppy and /cdrom as mount points while Redhat places them in /mnt/floppy and /mnt/cdrom respectively).

/opt

The /opt directory is used for the installation of third party or additional optional software that is not part of the default installation. Any applications installed in this area should be installed in such a way that it conforms to a reasonable structure and should not install files outside the /opt directory.

/proc

The /proc directory holds files that contain information about running processes and system resources. It can be described as a pseudo filesystem in the sense that it contains runtime system information, but not ‘real’ files in the normal sense of the word. For example the /proc/cpuinfo file which contains information about the computers cpus is listed as 0 bytes in length and yet if it is listed it will produce a description of the cpus in use.

/root

The /root directory is the home directory of the System Administrator, or the ‘root’ user. This could be viewed as slightly confusing as all other users home directories are in the /home directory and there is already a directory referred to as the ‘root’ directory (/). However, rest assured that there is good reason for doing this (sometimes the /home directory could be mounted on a separate file system that has to be accessed as a remote share).

/sbin

The /sbin directory is similar to the /bin directory in the sense that it holds binary executables / commands, but the ones in /sbin are essential to the working of the operating system and are identified as being those that the system administrator would use in maintaining the system. Examples of these commands are fdisk, shutdown, ifconfig and modprobe.

/srv

The /srv directory is set aside to provide a location for storing data for specific services. The rationale behind using this directory is that processes or services which require a single location and directory hierarchy for data and scripts can have a consistent placement across systems.

/tmp

The /tmp directory is set aside as a location where programs or users that require a temporary location for storing files or data can do so on the understanding that when a system is rebooted or shut down, this location is cleared and the contents deleted.

/usr

The /usr directory serves as a directory where user programs and data are stored and shared. This potential wide range of files and information can make the /usr directory fairly large and complex, so it contains several subdirectories that mirror those in the root (/) directory to make organisation more consistent.

/usr/bin

The /usr/bin directory contains binary executable files for users. The distinction between /bin and /usr/bin is that /bin contains the essential commands required to operate the system even if no other file system is mounted and /usr/bin contains the programs that users will require to do normal tasks. For example; awk, curl, php, python. If you can’t find a user binary under /bin, look under /usr/bin.

/usr/lib

The /usr/lib directory is the equivalent of the /lib directory in that it contains shared library files that supports the executable files for users located under /usr/bin and /usr/sbin.

/usr/local

The /usr/local directory contains users programs that are installed locally from source code. It is placed here specifically to avoid being inadvertently overwritten if the system software is upgraded.

/usr/sbin

The /usr/sbin directory contains non-essential binary executables which are used by the system administrator. For example cron and useradd. If you can’t locate a system binary in /usr/sbin, try /sbin.

/var

The /var directory contains variable data files. These are files that are expected to grow under normal circumstances For example, log files or spool directories for printer queues.

/var/lib

The /var/lib directory holds dynamic state information that programs typically modify while they run. This can be used to preserve the state of an application between reboots or even to share state information between different instances of the same application.

/var/log

The /var/log directory holds log files from a range of programs and services. Files in /var/log can often grow quite large and care should be taken to ensure that the size of the directory is managed appropriately. This can be done with the logrotate program.

/var/spool

The /var/spool directory contains what are called ‘spool’ files that contain data stored for later processing. For example, printers which will queue print jobs in a spool file for eventual printing and then deletion when the resource (the printer) becomes available.

/var/tmp

The /var/tmp directory is a temporary store for data that needs to be held between reboots (unlike /tmp).

Absolute and Relative Path Name Addressing

A strength of working with files from the command line in Linux is the flexibility and variety of options available to us as users. Some may claim that too many choices just makes it more difficult to know what is the right or wrong way to perform an action, but others (myself included) will propose that often there is no perfect way to carry out a task, there are only perfect ways.

What should be remembered is that the way that we choose to carry out a task should suit the task and the context. In that light there are plenty of options available in Linux and this is especially true when it comes to the process of specifying file locations.

Pathnames

A pathname represents a test string that acts as a pointer to a file or directory. The following pathname points to the file foo.txt which is inside the directory pi which is itself inside the directory home

The only ‘special’ or ‘reserved’ character when using a pathname is the forward slash /. This character is used solely to separate directories and file names as appropriate.

Individual directories and file names are typically restricted to 255 characters with a total length of a path restricted to 4096 characters. For the sake of context, there are approximately 1500 characters up until this point in this chapter.

Absolute Path Name Addressing

An absolute pathname will always start at the root directory (/). It’s an interesting quirk that people often identify the root directory as the forward slash, when it actually refers to a directory which has no name which exists on the left hand side of the / mark (remember that there can be no use of the / in directory or file names).

The following is an absolute pathname to the file foo.txt which is inside the directory pi which is itself inside the directory home which is in the root directory.

Relative Path Name Addressing

A relative pathname is one where the location of the file or directory is taken relative to the current directory the user is in.

For example, if we were in the directory home/pi (the ‘pi’ users home directory) and we wanted to list (ls) the file foo.txt we could use absolute addressing to reach the file by typing;

However, since we are in the directory /home/pi we could use relative addressing and simply type in;

To use relative addressing effectively we need to be able to let the computer know when we want to move up the directory hierarchy (moving down is done by simply typing the name of the directory). Moving up to a parent directory is accomplished by using the .. (dot dot) characters. If we imagine ourselves in the /home/pi directory again and want to list the file bar.txt which is in the /home/raspberry directory, we can type the following;

Here the .. characters first jumped up into the home directory and then went into the raspberry directory.

The ‘home’ short-cut

The tilde (~) character is used as a short cut to designate the home directory for a user. Therefore assuming that the ‘pi’ user has the home directory of /home/pi, but the directory that we (as the ‘pi’ user) are in is the /tmp directory, we can list the foo.txt file using the following relative path and the home shortcut character;

Everything is a file in Linux

A phrase that will often come up in Linux conversation is that;

Everything is a file

For someone new to Linux this sounds like some sort of ‘in joke’ that is designed to scare off the unwary and it can sometimes act as a barrier to a deeper understanding of the philosophy behind the approach taken in developing Linux.

The explanation behind the statement is that Linux is designed to be a system built of a group of interacting parts and the way that those parts can work together is to communicate using a common method. That method is to use a file as a common building block and the data in a file as the communications mechanism.

The trick to understanding what ‘Everything is a file’ means, is to broaden our understanding of what a file can be.

Traditional Files

The traditional concept of a file is an object with a specific name in a specific location with a particular content. For example, we might have a file named foo.txt which is in the directory /home/pi/ and it could contain a couple of lines of text similar to the following;

Directories

As unusual as it sounds a directory is also a file. The special aspect of a directory is that is is a file which contains a list of information about which files (and / or subdirectories) it contains. So when we want to list the contents of a directory using the ls command what is actually happening is that the operating system is getting the appropriate information from the file that represents the directory.

System Information

However, files can also be conduits of information. The /proc/ directory contains files that represent system and process information. If we want to determine information about the type of CPU that the computer is using, the file cpuinfo in the /proc/ directory can list it. By running the command `cat /proc/cpuinfo’ we can list a wealth of information about our CPU (the following is a subset of that information by the way);

Now that might not mean a lot to us at this stage, but if we were writing a program that needed a particular type of CPU in order to run successfully it could check this file to ensure that it could operate successfully. There are a wide range of files in the /proc/ directory that represent a great deal of information about how our system is operating.

Devices

When we use different devices in a Linux operating system these are also represented as a file. In the /dev/ directory we have files that represent a range of physical devices that are part of our computer. In larger computer systems with multiple disks they could be represented as /dev/sda1 and /dev/sda2, so that when we wanted to perform an action such as formatting a drive we would use the command mkfs on the /dev/sda1 file.

The /dev/ directory also holds some curious files that are used as tools for generating or managing data. For example /dev/random is an interface to the kernels random number device. /dev/zero represents a file that will constantly stream zeros (while this might sound weird, imagine a situation where you want to write over an area of disk with data to erase it). The most well known of these unusual files is probably /dev/nul. This will act as a ‘null device’ that will essentially discard any information sent to it.

Linux files and inodes

Having already established that everything is a file in a Linux operating system we find ourselves in the situation where files are suddenly slightly more interesting and mysterious, and it’s useful to get a better understanding of how files are represented in a Linux operating system so that the context of other functions can be better understood (thinking of links).

Linux files can be best understood by thinking of them as being described by three parts;

- The file name

- An inode

- The data

The file name

Individual file names are typically restricted to 255 characters and can be made up of almost any combination of characters. The only ‘special’ or ‘reserved’ character when assigning a file name is the forward slash (/). This character is used solely to separate directories and file names as appropriate.

The other component of a file name is an inode number. This is a number assigned by the operating system which acts as a pointer to an inode (Index Node) which is an object that can be thought of as an entry in a database that stores information specifically about that file.

We can list the inode numbers associated with files by using the -i option when listing files. For example;

The output (reproduced in edited form below) shows;

The numbers to the left of the file names are the associated inode numbers.

The file name and associated inode is in the directory that the file is contained in. Each directory (which is itself just a file) contains a table of the files it contains with the associated inode numbers.

The inode

Each file has an associated inode (index node). The inode is analogous to a database entry that describes a range of attributes of the file. These attributes include;

- The unique inode number

- Access Control List (ACL)

- Extended attributes such as append only or immutability

- Disk block location

- Number of blocks

- File access, change and modification time

- File deletion time

- File generation number

- File size

- File type

- Group

- Number of links

- Owner

- Permissions

- Status flags

You may well ask what the point of having numbered inodes is. Good question. They have a range of uses including being used when there are files to be deleted with complex file names that cannot be easily reproduced at the command line or enabling linking.

Interestingly, space for inodes must be assigned when an operating system is installed. Within any file-system, the maximum number of inodes, and hence the maximum number of files, is set when the file-system is created.

Therefore there are two ways in which a file-system can run out of space;

- It can consume all the space for adding new data (i.e. run out of hard drive space), or

- It can use up all the inodes.

Running out of inodes will bring a computer to a halt because exhaustion of the inodes prohibits the creation of additional files. Even if sufficient hard drive space exists. It is particularly easy to run out of inodes if a file-system contains a very large number of very small files.

links

A link in a Linux file system provides a mechanism for making a connection between files. While comparisons can be made to shortcuts in Windows, this is not terribly accurate as linking in Linux has a lot more utility.

To get the full benefit from the description of links we should be passingly familiar with the previous discussion on files and inodes. We should recall that a Linux file consists of three parts;

- The filename and it’s associated inode number

- An inode that describes the attributes of the file

- The data associated with the file.

The file name and inode number point to an inode that has all the information about the file and in turn points to the data stored on the hard drive.

Links can be identified when listing files with ls -l by a l that appears as the first character in the listing for th file and by the arrow (->) at the end that illustrates the link. For example by executing the following list command we can see (as only one amongst many files) that the file /etc/vtrgb is a link to the file /etc/alternatives/vtrgb.

Note the leading l and link sign for vtrgb in the output.

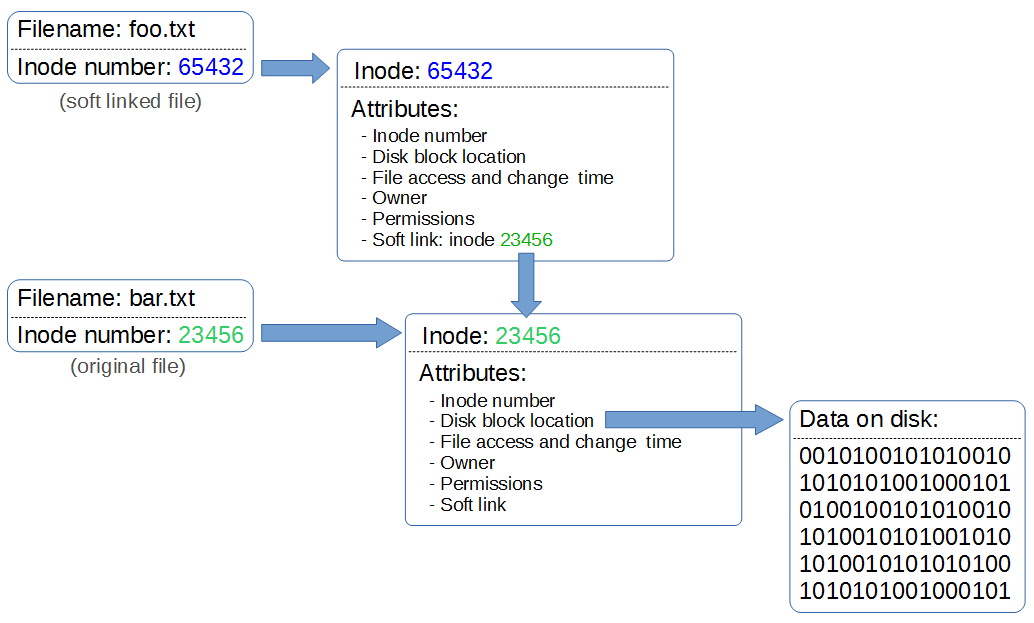

Soft Links (aka symbolic links, aka symlinks)

A soft link can also be referred to as a symbolic link, but is probably more frequently called a ‘symlink’. A symlink has a file name and inode number that points to it’s own inode, but in the inode there is a path that redirects to another inode that in turn points to a data block.

Because inodes are restricted to the partition they are created on, a symbolic link allows redirecting to a path that can cross partitions.

If we edit the linked file, the original file will be edited. If we delete the linked file, the original file will not be deleted. But if we delete the original file without deleting the link, we will be left with an orphaned link.

Soft links can link to directories and files but if the file is moved the link will no longer work.

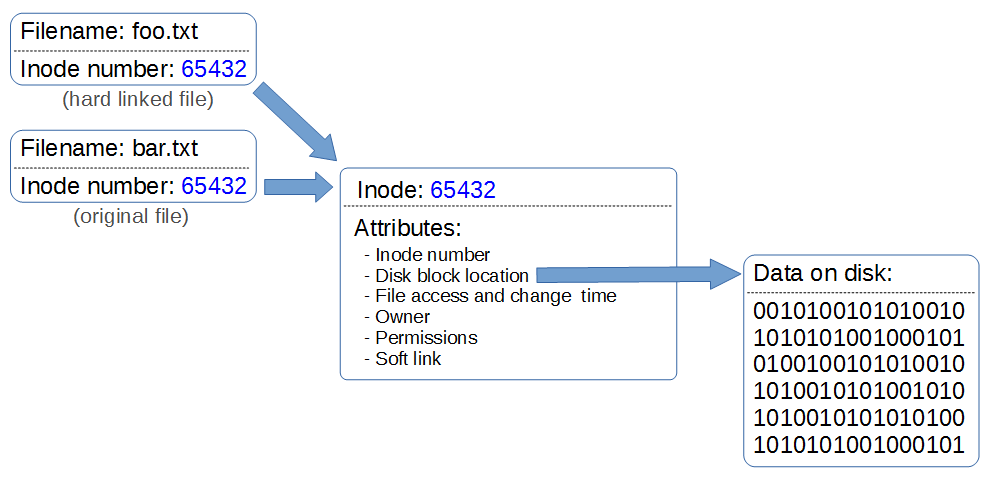

Hard Links

A hard link is one where more than one file name links to an inode.

This means that two file names are essentially sharing the same inode and data block, however they will behave as independent files. For example if we then delete one of the files the link is broken, but the inode and data block will remain until all the file names that link to the inode are deleted.

Hard links only link to a file (no directories), cannot span partitions and will still link to a file even if it is moved.

Links Compared

Hard links

- Will only link to a file (no directories)

- Will not link to a file on a different hard drive / partition

- Will link to a file even when it is moved

- Links to an inode and a physical location on the disk

Soft links (or symbolic links or symlinks)

- Will link to directories or files

- Will link to a file or directory on a different hard drive / partition

- Links will remain if the original file is deleted

- Links will not connect to the file if it is moved

- Links connect via abstract (hence symbolic) conventions, not physical locations on the disk. They have their own inode

File Editing

Working in Linux is an exercise in understanding the concepts that Linux uses as its foundations such as ‘Everything is a file’ and the use of wildcards, pipes and the directory structure.

While working at the command line there will very quickly come the realisation that there is a need to know how to edit a file. Linux being what it is, there are many ways that files can be edited.

An outstanding illustration of this is via the excellent cartoon work of the xkcd comic strip (Buy his stuff, it’s awesome!).

For a taste of the possible options available Wikipedia has got our back. Inevitably where there is choice there are preferences and where there are preferences there is bias. Everyone will have a preference towards a particular editor and don’t let a particular bias influence you to go down a particular direction without considering your options. Speaking from personal experience I was encouraged to use ‘vi’ as it represented the preference of the group I was in, but because I was a late starter to the command line I struggled for the longest time to try and become familiar with it. I know I should have tried harder, but I failed. For a while I wandered in the editor wilderness trying desperately to cling to the GUI where I could use ‘gedit’ or ‘geany’ and then one day I was introduced to ‘nano’.

This has become my preference and I am therefore biased towards it. Don’t take my word for it. Try alternatives. I’ll describe ‘nano’ below, but take that as a possible path and realise that whatever editor works for you will be the right one. The trick is simply to find one that works for you.

The nano Editor

The nano editor can be started from the command line using just the command and the /path/name of the file.

If the file requires administrator permissions it can be executed with ‘sudo`.

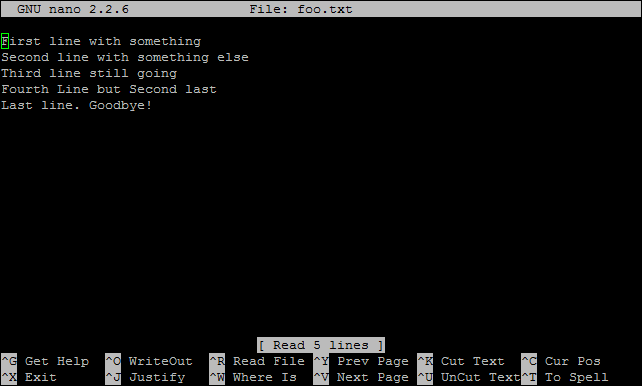

When it opens it presents us with a working space and part of the file and some common shortcuts for use at the bottom of the console;

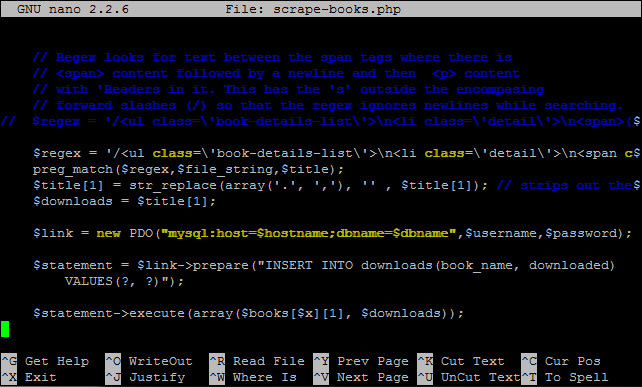

It includes some simple syntax highlighting for common file formats;

This can be improved if desired (cue Google).

There is a swag of shortcuts to make editing easier, but the simple ones are as follows;

- CTRL-x - Exit the editor. If we are in the middle of editing a file we will be asked if we want to save our work

- CTRL-r - Read a file into our current working file. This enables us to add text from another file while working from within a new file.

- CTRL-k - Cut text.

- CTRL-u - Uncut (or Paste) text.

- CTRL-o - Save file name and continue working.

- CTRL-t - Check the spelling of our text.

- CTRL-w - Search the text.

- CTRL-a - Go to the beginning of the current working line.

- CTRL-e - Go to the end of the current working line.

- CTRL-g - Get help with nano.

Scripting

A shell script is a file containing a series of commands. The process of scripting is the writing of those commands in the file. The shell can read this file and act on the commands as if they were typed at the keyboard.

Because there are many commands available to use we can realise the real power of computing and the reduction of repetitive tasks by automating processes.

Think of shell scripts as program commands which are chained together and which the system can execute as a scripted event. They make use of functions such as command substitution where we can invoke a command, like date, and use it’s output as part of a file-naming scheme. Scripts are programs in their own right which use programming functions such as loops, variables and if/then/else statements. The beauty of scripting is that we don’t have to learn another programming language to script effectively, we simply use the commands we use at the command line.

To successfully write a script to do something we have to do three things;

- Write a script (a file with a ‘.sh’ extension) that uses common commands.

- Set the permissions on the file so that it can be executed

- Place the file somewhere that the shell can locate it when it’s invoked

Writing our Script

The script itself is just a text file. The only thing fancy about it is that it contains commands and we’re going to make it executable.

We can start with a simple example that demonstrates echoing a simple message to the screen.

Starting in our home directory (/home/pi) we can use the nano editor to create our script by running the following command;

This will open the nano editor and we can type in something like the following;

#!/bin/bash

# Hello World Script

echo "Hello World!"

The first line of the script is important because it provides information to the shell about what program should be used to interpret and run the script. The line starts with a ‘shebang’ (#!) and then the path to the program (in this case /bin/bash).

The second line is a comment that we would place in a script to tell ourselves or others that open the file what is going on. Anything that appears after a # mark (except for on the first line with the ‘shebang’) will be ignored by the script and is entered to make notes for the reader.

The last line is the command we will run. In this case it only one command, but it could also be any number. The command in this case is a very simple echo command to print the words ‘Hello World!’ to the screen.

Once finished we can close and save the file (CTRL-x to close and say ‘y’ to save);

That’s our script written.

Make the script executable

If we list the properties of our file sayhello.sh with ls as follows;

… we will see the details of the file something like this;

1 pi pi 54 Feb 17 17:18 sayhello.sh

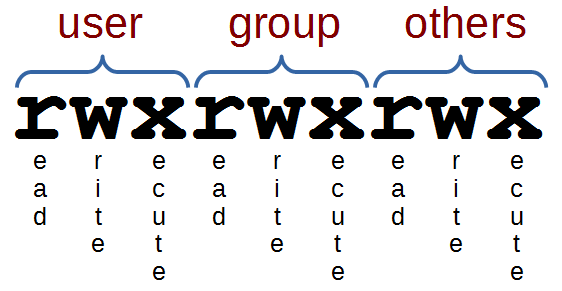

Linux permissions specify what the owning user can do, what a member of the owning group can do and what other users can do with the file. For any given user, we need three bits to specify access permissions: the first to denote read (r) access, the second to denote (w) access and the third to denote execute (x) access.

We also have three levels of ownership: ‘user’, ‘group’ and ‘others’ so we need a triplet (three sets of three) for each, resulting in nine bits.

The following diagram shows how this grouping of permissions can be represented on a Linux system where the user, group and others had full read, write and execute permissions;

The permissions of our sayhello.sh file tell us that the user can read and write the file, members of the group and anyone else can read the file. What we need to do is to make it executable using the chmod command

If we check again with ls -l sayhello.sh we should see something similar to this;

1 pi pi 54 Feb 17 17:18 sayhello.sh

Here everyone has execute permissions and the ‘pi’ user and the ‘pi’ group have read and write permissions.

Place the script somewhere that the shell can find it

Currently we’re working in the ‘pi’ home directory where we’ve saved our file. This should be the easiest example of making the script accessible and as such we should be able to simply run the command directly from the command line as follows;

The output from the command should look something like this;

The ./ notation in front of the script designates the path to the file being our current directory. We could have also provided the full path as follows;

(Since /home/pi/ is the directory that the file is currently in.)

So that works, but in the perfect world we wouldn’t need to designate a path to the script in order to execute it. We can make that happen by placing the script in one of the directories in the users ‘PATH’.

PATH is an environmental variable that tells the shell which directories to search for executable files. It should not be confused with the term ‘path’ which refers to a file’s or directory’s address in a files system

A user’s PATH consists of a series of colon-separated absolute paths. When we type in a command at the command line that is not distributed with the operating system or which does not include its absolute path and then the shell searches through the directories in PATH, which constitute the our search path, until it finds an executable file with that name.

We can check what the paths available are by echo-ing the PATH variable to the screen like so;

This will then report PATH to the screen something like the following

We can therefore add our script to any of those directories and it will work like a normal command. However, this will make it available to all users on the system and if we want to only make it available to ourselves as the current user we will need to add a new path to PATH.

The good news is that this is simple to do and in Debian Jessie all we need to do is to create a directory in our home directory (if we are logged in as the ‘pi’ user, that would be /home/pi) called bin. We can place any script that we want to be available to the ‘pi’ user in there and they will have access to it. The reason they will have access is that while it doesn’t appear in PATH at the moment, when we add the bin directory to our home directory, there is a script called .profile which gets checked whenever we start our bash shell. If .profile sees that we have a bin directory in our home directory it adds it to our PATH.

So if we add the directory using mkdir as follows;

… we will be set up with a new path in PATH the next time we start our shell.

Let’s not forget that we should move our file into our new directory with mv as follows;

If we open a new terminal and log on as our user (it’s ‘pi’ in the example) we can how go anywhere (cd) in the directory structure and simply run the command;

… and get the response;

That’s the completion of our simple first example. More advanced work with loops, variables and if/then/else statements will have to be an exercise for the reader. Hopefully that’s ‘Just Enough’ to get you started.