Introduction

The Fantastic Feeling of Delivery

Wow! You made it!

The project just closed with delivery on time, or at least with an acceptable minor delay. You are exhausted and exhilirated and you just want to kiss your team mates and the world.

What looked like impossible a few weeks ago has been achieved by your team, raising to the challenge and working together like never before. The dispute about the seating arrangement was forgotten. The irritation between the senior guy and the new lady was set aside. The previously stiff control freak handling the quality assurance has loosened up and has given great suggestions to the team where to focus to ensure the critical elements and maybe review the less important aspects later. How did this happen?

This book is about the many little things that makes international projects successful.

What is a Project?

“A project is a temporary endeavor designed to produce a unique product, service or result with a defined beginning and end.”, Wikipedia 2015 [^WikipediaProject]

There is a project leader who takes responsibility for the delivery and who has the authority to lead the people involved and to decide how to use the alotted resources.

The vocabulary around workplace projects took form during the last century. Pioneers like Henry Gantt (who invented the Gantt Charts to illustrate scheduled activities) laid a foundation in the early 1900s. After the World War II, the large industrial projects in the US were formed into formal projects for governance and control. Gantt charts became a commonplace tool to identify dependecies and to find the shortest possible time to finish a project - the critical path.

During the 1960’s, project management became formalized in many organizations. At IBM, that era’s world leader in computer hardware and software, Frederick Brooks led the development of System/360. It became that time’s most successful computer system that completely dominated the market. Brooks described his experiences in the essay collection The Mythical Man-Month[^BrooksMythicalManMonth]. He identified two critical problems in software development projects: learning and communication. Therefore, adding people in the middle of a project often leads to a longer duration of the project. The title of the book alludes to the fallacy of top managers to think that adding a person to the team automatically reduces the lead-time of a project. In reality, the new person needs training which takes energy away from the project and it increases communication complexity.

During the 2000’s, there are two conflicting trends: detail vs. flexibility. On one hand, some project planners are ecstatic about the advanced computer tools that allow detailed activity description of every work package before the project starts - which is excellent when there is high complexity and little uncertainty. Examples are often seen in building/construction business and the automotive sector when you do an upgrade of an existing vehicle. Hundreds of people will be involved at specific times and the complexity is overwhelming. However, the description of end goal can be quite detailed and accurate. This kind of projects are well served by classic project management methods like PRINCE2 [^WikipediaPrince2] or the Waterfall Method [^WikipediaWaterfall].

On the other hand, other projects run with high uncertainty and cannot be planned upfront. The exact details of the solution are not known. In those cases there are other methods (e.g. Agile [^AgileManifesto]) that help to converge to delivery. Typical examples are theatre productions or development of new computer software. When the details are less clear, a significant part of the project is to clarify the unknowns, and thereby converge to a solution based on the time/resources available.

In this book there are examples of projects of both kinds. Think about your organization - what kind of projects do you run? Which methods do you use? Are they suitable for your projects? Where are the pain points?

Sometimes the end-goal is not crystal clear. Detailed planning up front does not help in this case.

A Project or a Process?

Some organizations try to organize everything as a project. I think this is a mistake, since there are certain disadvantages with the project form for an activity.

Every project is inherently inefficient, since it is a one-off activity. Everything that is done once needs a lot of learning, many decisions and will inevitably lead to waiting times. One-off activities like projects contain lots of waste (in the Lean[^WomackLeanThinking]-parlance). Projects as a whole are impractical to automate.

Whenever an organization has repetitive work, it is better to convert it into a well defined process - where you can use all the Lean tools to continuously improve efficiency and effectiveness, and reduce the number of decision points.

Therefore, whenever you work on a project, look at which of the activities you do are likely to occur again. What can you describe as a process? What can you document? What can you automate? The process definition is then a deliverable of your project, so that it will run smoother next time.

Whenever your project creates a good process, this process will continue to generate value for the organization year after year, long after the closure of the project. A process is the result of an investment in time and effort. In a certain sense, an established process is a form of intellectual capital that generates value over and over again. A good process is as valuable as a good machine to generate value. The same holds for creation of training material, work instructions and software tools that will be used again and again.

The Lean philosophy to increase customer value and reducing waste in the process is well established for manufacturing processes [^LikerToyotaWay]. It has been recently introduced for start-ups [^RiesLeanStartup]. For projects, there is not yet a formalized “lean method”, but the same thinking is relevant. When you get your team to agree on what is customer value and how this is embodied in your delivery, you are already more than half-way.

The Project Leader

In this book, we call the person who runs the project the project leader, but in your organization it may be called project manager or lead engineer or something else. This book focuses on the role of the project leader but there are observations that can be useful for everyone in the project team. It is quite useful to run a training on project leadership for all participants in your project, so that you all use the same words - every training is part language, part content. You can also use a book (like this one) as prescribed reading, so that you mean the same thing when you talk about a “sponsor” or a “red flag”.

In some organizations, there is a formal project structure with well-defined roles and responsibilities [^DinsmoreTheRightProject]. In other places, the projects have less formal support and the project leader needs to clarify the responsibilities. Sometimes projects are not even called projects. (One example was when I established a product development team in China. This was a three year long project with the goal to have a working team in place with the right processes and getting real products to the market. This was not a “project” in the company vocabulary. Nevertheless, I ran it as a project.)

In your organization - do you have dedicated, designated project leaders? Or is this a side-job?

Sponsor

We call the person who wants the project to happen the sponsor. The sponsor ensures that there is budget and officially appoints the project leader. There is a symbiosis between the sponsor and project leader, you are dependent on each other.

Often, the project leader develops the project plan and gets agreement from the sponsor. The sponsor is the first escalation point for any deviation that the project cannot handle internally. For small projects a sponsor is enough for governance. For medium size projects, especially when the team consists of people from different departments, it is useful to collect their managers into a steering committee.

We will come back to the sponsor and the steering committee in the chapter about The Matrix.

Phases and Gates

When projects grow in size and in time, it is useful to break it down into separate blocks, here called phases. At the onset of each new phase, collect your steering committee and team members to review the plan for the next phase and hold a gate meeting. The main objective is to ensure that the project moves in the right direction into the next phase. Sometimes this is called a gate opening meeting, implying that the gate into the next phase is closed until you all agree to open it and continue.

In some organizations, the tollgate meetings are held to check that you have done what you promised in the previous phase, but that is typically a sign of distrust and a waste of smart people’s time. It is better to use the access you have to senior management in your steering committee to get their best advice on how to move forward, so that you are aligned with the de facto strategy of your organization.

The temptation is strong to look back and present everything that you have done, to show your hard work, your achievements and to get recognition. Think again and see how you can use the limited time available to get decisions that help you to reach final delivery faster.

Why Projects Fail

There are powerful, invisible forces in play that work against every project. Project team members change jobs or lose interest. Reorganizations shuffle stakeholders around. You get dragged into other activities. Political interests shift and the project budget is reduced.

This is the dark side of working in large organizations and not often openly discussed. You hear the complaints around the water cooler and over lunch. Cynical remarks about top managers decision making. Some people turn bitter when their favourite projects are neglected after years of dedicated toil. Still, it is the project leader who has to defend the lack of delivery in the next performance review.

However, I do not believe that there is an intentional sabotage on the part of the line management, it is just a systemic disadvantage that projects have to handle. Resource management and allocated budgets are typically part of the line organization and projects therefore implicitly get second priority.

Nevertheless, to enjoy project management it is important to be aware of the uphill struggle to the finishing line. The more you know about potential pitfalls, the more agile you can act. The sooner you identify possible problems, the more you can do to avoid them. If you are the first person to identify a certain risk, you can manage expectations, modify the scope and lead your project to a complete conclusion. The real-life examples in this book illustrate typical project problems and this can help you to identify issues in your own projects as early as possible.

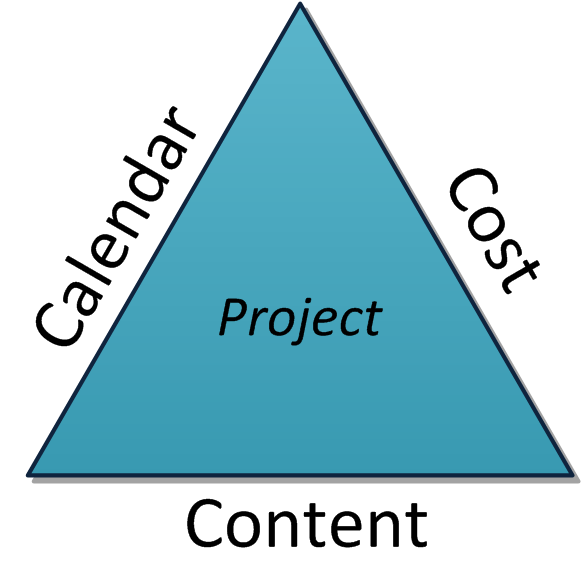

Project with triple-constraints. Most projects are initially over-constrained, describing an impossible combination of calendar/content/cost. One of your jobs is to get your project into the triangle.

Sometimes a project is defined as an operation within triple-constraints of calendar-cost-content (or scope-cost-time). The objective is to deliver the right product content (scope) within the given calendar time at the right cost. In reality, projects are often over-constrained, so that it is impossible to deliver the complete scope in time and within budget. Therefore is your responsibility to bring this into the light as early as possible to sharpen the scope or extend budget and time.

Project Management Dimensions

This book is about achieving Delivery and avoiding disaster. It is organized in four sections, describing four different aspects of a project. We start with the end in mind [^CoveySevenHabits].

Therefore we start with a focus on the Delivery in the first section. We look at critical factors to ensure customer acceptance and how to converge to a closure. The main takeaway is the value of clear, indisputable targets based on what the customer values. These targets are useful at the outset and indispensable at the end.

Section two is about the Team, the engine of your project and your main concern. Your people make it happen and are your most valuable resource. (This sounds like a cliché, but it is really true. Alone you can do nothing.) Most of your attention during the course of the project will be on your team. This is an additional challenge for international projects when your team is spread across several nationalities and locations.

We then zoom out to the Matrix, the organizational force field in which you operate. Being project leader gives you much freedom to influence, even though your formal authority is minimal. Therefore, the methods of indirect power allow you to build momentum to push your project over hurdles that may arise. The mix of managers and reporting lines often delay decisions and cloud clarity, so your consistent, convincing communication into this fog can free your team from frustrations.

Finally, we look at you, the Project Leader. Where do your values and personality come to full bloom? When do your eyes glisten from enthusiasm? This chapter gives you tools to search for your grounding and to get going in a direction that matters to you.

Each chapter is dotted with real life stories from international projects that illustrate the material. World class project managers from different backgrounds have contributed with their insights and tips. Many of the stories are from the projects I led in Sweden, Russia, France, Holland and China.

The observations help you to identify problematic situations when they arise in your projects. Hopefully, you will be faster to react and have more time to develop constructive solutions.

Privacy and Names

Throughout the book, there are numerous stories from real-life projects. I would like to thank all the interesting people I have had the privilege to work with over the years. To respect your privacy I have chosen to change the names of everybody. Nevertheless, I am sure that you recognize yourself…

In the contributions from the international experts, some sensitive company details have been changed to protect competitive advantage and to avoid embarrassment.

Additional Material

Additional material and discussion about international project management is found at the companion website: www.deliver-book.com

Please join the discussion and share your stories from your projects. We can learn a lot from each others’ experiences, success stories and disasters.