Introduction

Who is Building Conduit for?

This book is written for anyone who has an interest in CQRS/ES and Elixir.

It assumes the reader will already be familiar with the broad concepts of CQRS/ES. You will be introduced to the building blocks that comprise an application built following this pattern, and shown how to implement them in Elixir.

The reader should be comfortable reading Elixir syntax and understand the basics of its actor concurrency model, implemented as processes and message passing.

What does it cover?

You will learn an approach to implementing the CQRS/ES pattern in a real world Elixir application. You will build a Medium.com clone, called Conduit, using the Phoenix web framework. Conduit is a real world blogging platform allowing users to publish articles, follow authors, and browse and read articles.

The inspiration for this example web application comes from the RealWorld project:

See how the exact same Medium.com clone (called Conduit) is built using any of our supported frontends and backends. Yes, you can mix and match them, because they all adhere to the same API spec.

While most “todo” demos provide an excellent cursory glance at a framework’s capabilities, they typically don’t convey the knowledge & perspective required to actually build real applications with it.

RealWorld solves this by allowing you to choose any frontend (React, Angular 2, & more) and any backend (Node, Django, & more) and see how they power a real world, beautifully designed fullstack app called “Conduit”.

By building a backend in Elixir and Phoenix that adheres to the RealWorld API specs, you can choose to pair it with any of the available frontends. Some of the most popular current implementations are:

You can view a live demo of Conduit that’s powered by React and Redux with a Node.js backend, to get a feel for what we’ll be building.

Many thanks to Eric Simons for pioneering the idea and founding the RealWorld project.

Before we start building Conduit, let’s briefly cover some of the concepts related to command query responsibility segregation and event sourcing.

What is CQRS?

At its simplest, CQRS is the separation of commands from queries.

- Commands are used to mutate state in a write model.

- Queries are used to retrieve a value from a read model.

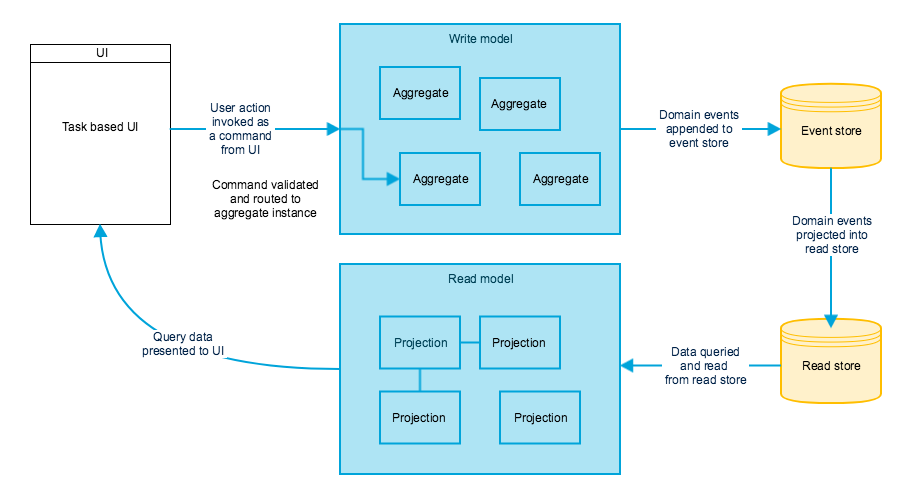

In a typical layered architecture you have a single model to service writes and reads, whereas in a CQRS application the read and write models are different. They may also be separated physically by using a different database or storage mechanism. CQRS is often combined with event sourcing where there’s an event store for persisting domain events (write model) and at least one other data store for the read model.

Commands

Commands are used to instruct an application to do something, they are named in the imperative:

- Register account

- Transfer funds

- Mark fraudulent activity

Commands have one, and only one, receiver: the code that fulfils the command request.

Domain events

Domain events indicate something of importance has occurred within a domain model. They are named in the past tense:

- Account registered

- Funds transferred

- Fraudulent activity detected

Domain events describe your system activity over time using a rich, domain-specific language. They are an immutable source of truth for the system. Unlike commands which are restricted to a single handler, domain events may be consumed by multiple subscribers - or potentially no interested subscribers.

Often commands and events come in pairs: a successful register account command results in an account registered event. It’s also possible that a command can be successfully executed and result in many or no domain events.

Queries

Domain events from the write model are used to build and update a read model. I refer to this process as projecting events into a read model projection.

The read model is optimised for querying therefore the data is often stored denormalized to support faster querying performance. You can use whatever technology is most appropriate to support the querying your application demands, and take advantage of multiple different types of storage as appropriate:

- Relational database.

- In-memory store.

- Disk-based file store.

- NoSQL database.

- Full-text search index.

What is event sourcing?

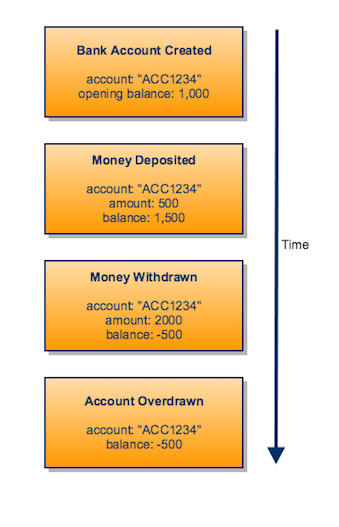

Any state changes within your domain are driven by domain events. Therefore your entire application’s state changes are modelled as a stream of domain events:

An aggregate’s state is built by applying its domain events to some initial empty state. State is further mutated by applying a created domain to the current state:

Domain events are persisted in order – as a logical stream – for each aggregate. The event stream is the canonical source of truth, therefore it is a perfect audit log.

All other state in the system may be rebuilt from these events. Read models are projections of the event stream. You can rebuild the read model by replaying every event from the beginning of time.

What are the costs of using CQRS?

Domain events provide a history of your poor design decisions and they are immutable.

It’s an alternative, and less common, approach to building applications than basic CRUD1. Modelling your application using domain events demands a rich understanding of the domain. It can be more complex to deal with the eventual consistency between the write model and the read model.

Recipe for building a CQRS/ES application in Elixir

- A domain model containing aggregates, commands, and events.

- Hosting of an aggregate root instance and a way to send it commands.

- An event store to persist the created domain events.

- A Read model store for querying.

- Event handlers to build and update the read model.

- An API to query the read model data and to dispatch commands to the write model.

An aggregate

An aggregate defines a consistency boundary for transactions and concurrency. Aggregates should also be viewed from the perspective of being a “conceptual whole”. They are used to enforce invariants in a domain model and to guard against business rule violations.

This concept fits naturally within Elixir’s actor concurrency model. An Elixir GenServer enforces serialised concurrent access and processes communicate by sending messages (commands and events).

An event sourced aggregate

Must adhere to these rules:

- Public API functions must accept a command and return any resultant domain events, or an error.

- Its internal state may only be modified by applying a domain event to its current state.

- Its internal state can be rebuilt from an initial empty state by replaying all domain events in the order they were raised.

Here’s an example event sourced aggregate in Elixir:

defmodule ExampleAggregate do

# Aggregate's state

defstruct [:uuid, :name]

# Public command API

def create(%ExampleAggregate{}, uuid, name) do

%CreatedEvent{

uuid: uuid,

name: name,

}

end

# State mutator

def apply(%ExampleAggregate{} = aggregate, %CreatedEvent{uuid: uuid, name: name}) do

%ExampleAggregate{aggregate | uuid: uuid, name: name}

end

end

It is preferable to implement aggregates using pure functions2. Why might this be a good rule to follow? Because a pure function is highly testable: you will focus on behaviour rather than state.

By using pure functions in your domain model, you also decouple your domain from the framework’s domain. Allowing you to build your application separately first, and layer the external interface on top. The external interface in our application will be the RESTful API powered by Phoenix.

Unit testing an aggregate

An aggregate function can be tested by executing a command and verifying the expected events are returned.

The following example demonstrates a BankAccount aggregate being tested for opening an account:

defmodule BankAccountTest do

use ExUnit.Case, async: true

alias BankAccount.Commands.OpenAccount

alias BankAccount.Events.BankAccountOpened

describe "opening an account with a valid initial balance"

test "should be opened" do

account = %BankAccount{}

open_account = %OpenAccount{

account_number: "ACC123",

initial_balance: 100,

}

event = BankAccount.open_account(account, open_account)

assert event == %BankAccountOpened{

account_number: "ACC123",

initial_balance: 100,

}

end

end

end