Don’t worry too much about story format

There is plenty of advice out there about different formats of story cards. Some argue that putting the business value statement first focuses delivery on business value, some argue that ‘So that I can’ is a much better start than ‘In order to’, and we’ve heard passionate presentations about how ‘I suggest’ is better than ‘I want’. We’re going to swim against the current here and offer a piece of controversial advice: don’t worry too much about the format!

There are three main reasons why you shouldn’t trouble yourselves too much with the exact structure of a user story, as long as the key elements are there:

- A story card is ideally just a token for a conversation. Assuming the information on the card is not false, any of the formats is good enough to start the discussion. If the information on the card is false, they are all equally bad.

- Although we’ve read and heard plenty of arguments for different card types, there wasn’t a single clear proof that choosing one format over another improved team performance by a significant amount. Show us where reordering statements on a story card improved profit by more than 1% and we’ll talk.

- As an industry, we love syntax wars. If you ever need proof that IT is full of obsessive-compulsive types, look up on the web the best indentation level, the undoubted superiority of tabs over spaces, or the most productive position for curly braces. Beyond the obvious argument about personal preference, there is value in choosing one standard way for writing code for the entire team, regardless of what gets chosen. But code is a long-term artefact, and user stories are discussion reminders that have served their purpose after a conversation. So the standardisation argument does not really apply here.

The Connextra card template (‘As a… I want … So that’) is a great structure for a discussion token. It proposes a deliverable and puts it in the context of a stakeholder benefit, which helps immensely with the discussion. But that’s not the only way to start a good conversation. As long as the story card stimulates a good discussion, it serves its purpose. Write down who wants something and why they want it in any way you see fit, and do something more productive with the rest of your time than filling in a template just because you have to. For example, make sure that the person in question is actually a stakeholder, and that they actually want what the card says.

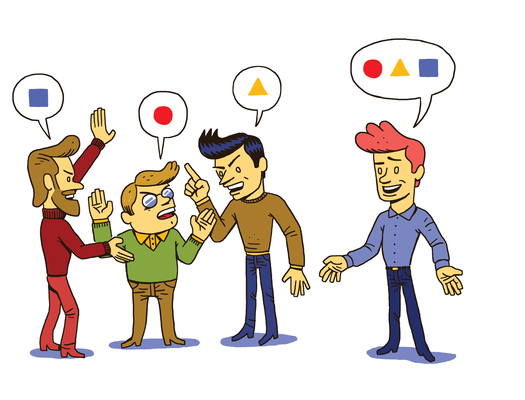

An interesting take on this is to experiment with different formats to see if something new comes out during discussion. For example:

- Name stories early, add details later

- Avoid spelling out obvious solutions

- Think about more than one stakeholder who would be interested in the item – this opens up options for splitting the story

- Use a picture instead of words

- Ask a question

Chris Matts, one of the agile business analysis thought-leaders, has a nice example:

My favourite story card had the Japanese Kanji characters Ni and Hon (the name for Japan in native script) on it. Nothing else. It was the card for Japanese language translation.

When we wrote this, Gojko was working on a product milestone that was mostly about helping users obtain information more easily. Most user stories for the milestone were captured as examples of questions people would be able to answer, such as: ‘How much potential cash is there in blocked projects?’ and ‘What is the average time spent on sales?’. These are perfectly good stories, as they fulfil both important roles nicely: they allow delivery teams to schedule things and they spark a good discussion. Each question is just an example, and leads to a discussion on the best way of providing information to users to answer a whole class of related questions. Forcing the stories into a three-clause template just for the sake of it would not give the team any more benefit, and it might even mislead the discussion as it would limit it to only one solution.

Key benefits

Letting go of a template, and trying out different formats, can help to shake up the discussion. This also helps to prevent fake stories. Following a template just for the sake of it is a great way to build a cargo cult. This is where stories such as ‘As a trader I want to trade because I want to trade’ come from, as well as ‘As a System I want the … report’.

By trying out different formats, you might wake up some hidden creativity in the team, or discover a different perspective during the discussion about a story.

How to make it work

The one thing you really have to do to make this work is to avoid feature requests. If you have only a short summary on a card, it must not be a solution without context. So, ‘How much potential cash is in blocked projects?’ is a valid summary, but a ‘Cash report’ isn’t. The potential cash question actually led to a pop-up dialog that presented a total of cash by status for any item in the document, not to a traditional tabular report.

Focus on the problem statement, the user side of things, instead of on the software implementation. The way to avoid trouble is to describe a behaviour change as the summary. For example ‘Get a profit overview faster’, or ‘Manage deliveries more accurately’.