Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Sleeping

-

Transit

-

JR Pass

- Types of JR Passes

- How to buy a JR Pass

- Using a JR Pass for JR Trains

- Dear Google: PLEASE Add a “JR Pass Only” or “Exclude Nozomi and Mizuho” Option to Google Maps

- Dear Google: While You’re At It, Japanese is Not Chinese

- Other Places to use a JR Pass

- How To Use a JR Pass

- Why You May Not Want a JR Pass for Tokyo

- Suica (or Pasmo) Card: Get One Immediately

- Google Maps is Essential

- Metro and Trains

- City Buses

- Highway Buses

- Taxis

-

JR Pass

- How & What to Pack

- Convenience Stores, Vending Machines & Bank Machines

- Food

- Shopping

- Laundry

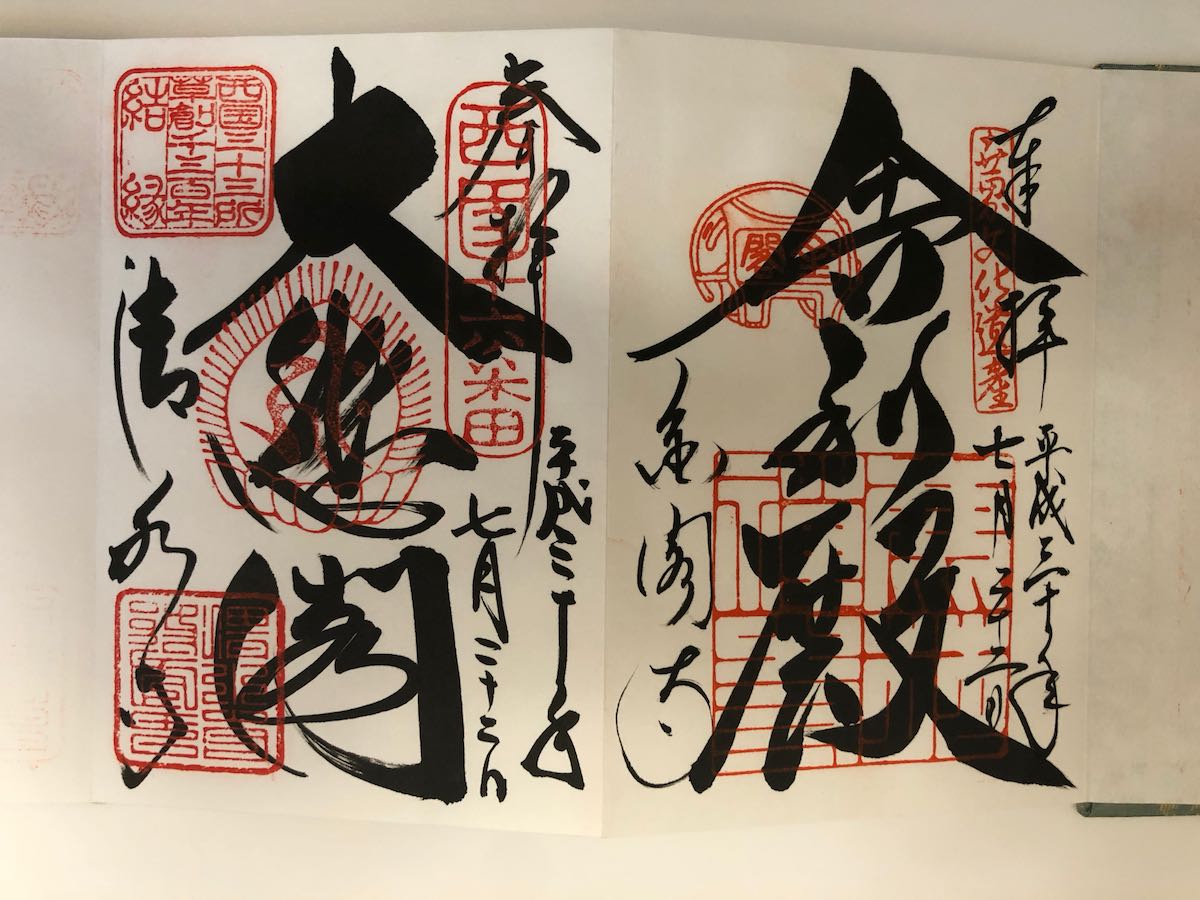

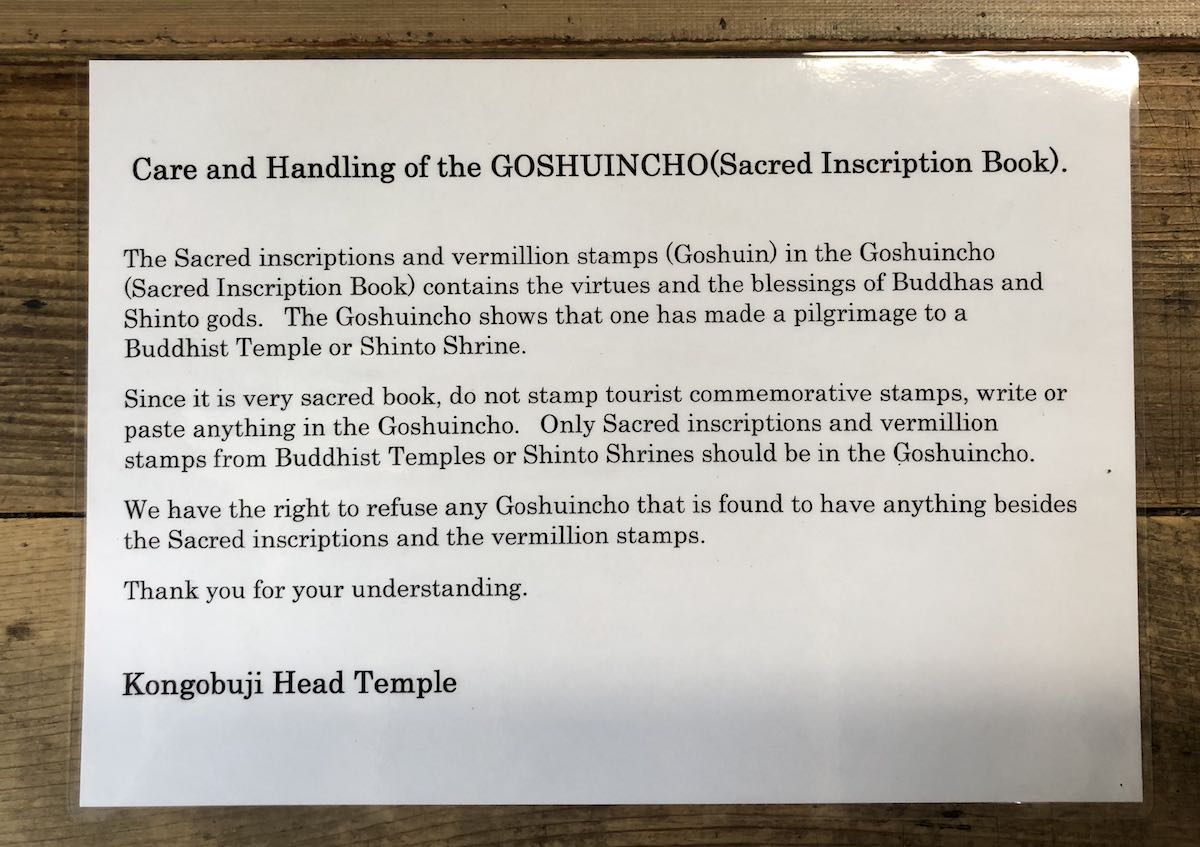

- Goshuincho and Goshuin

- Etiquette

- Communicating Without Speaking (Much) Japanese

- Itinerary Advice

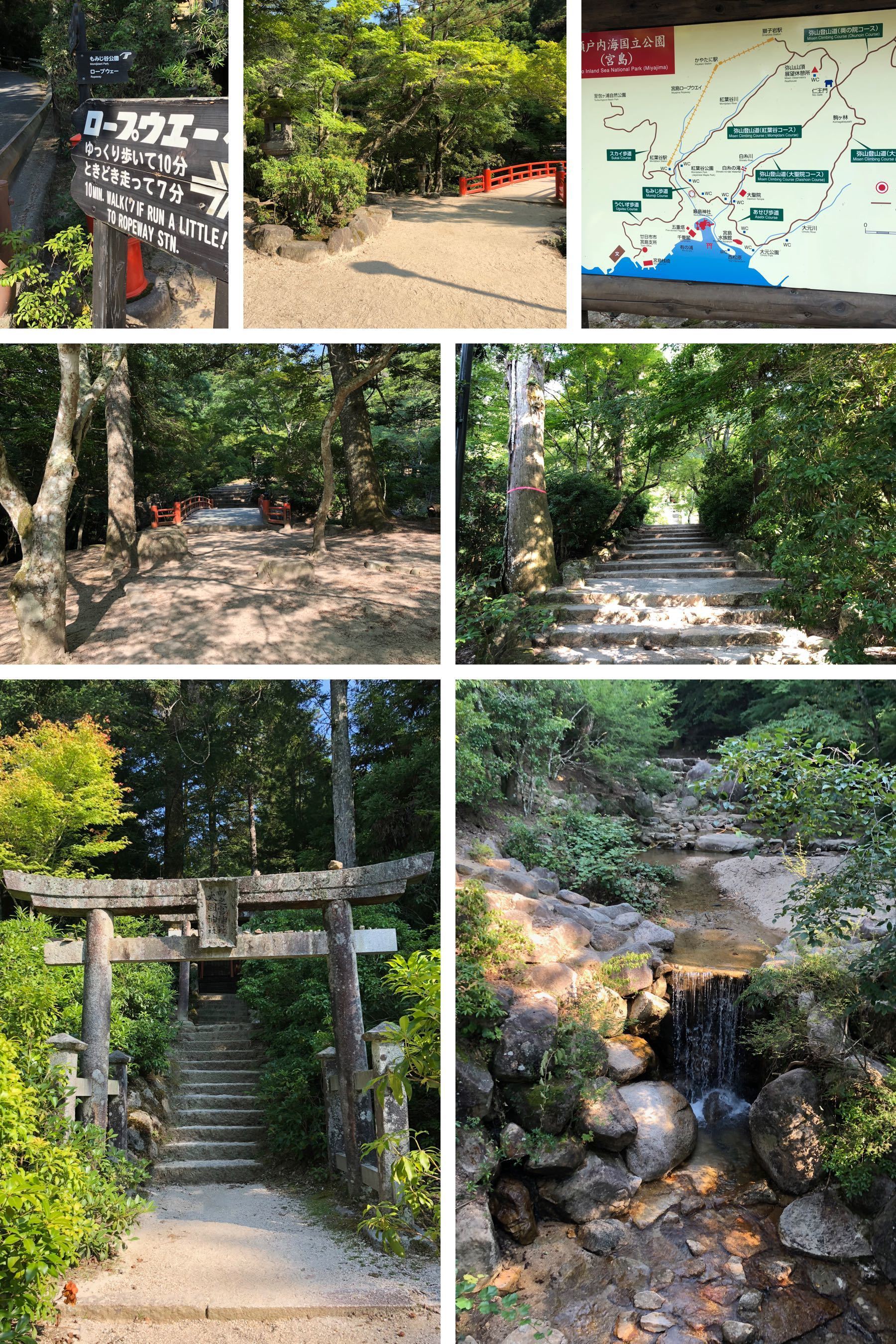

- Hiking

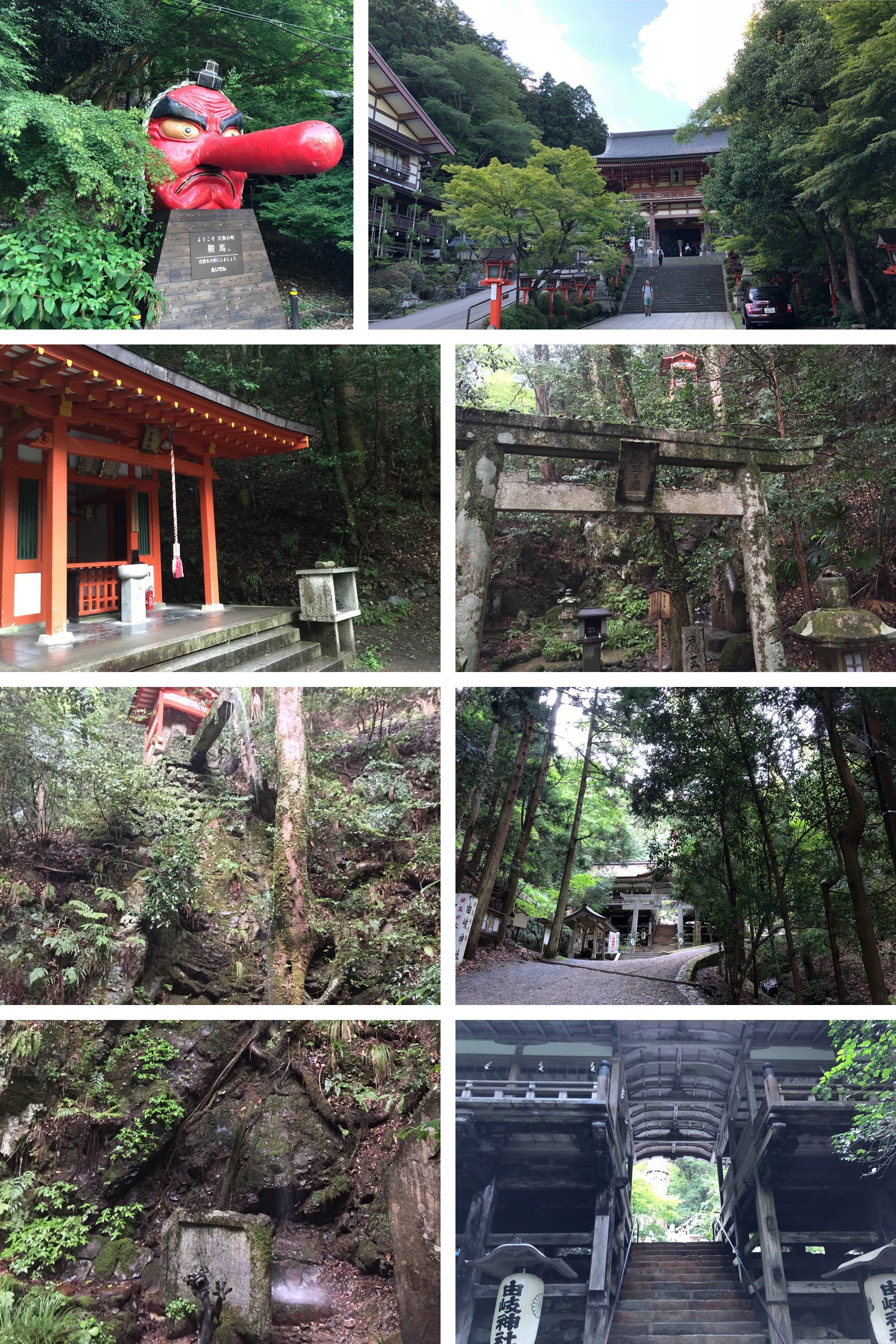

- Temples and Shrines

- Castles and Gardens

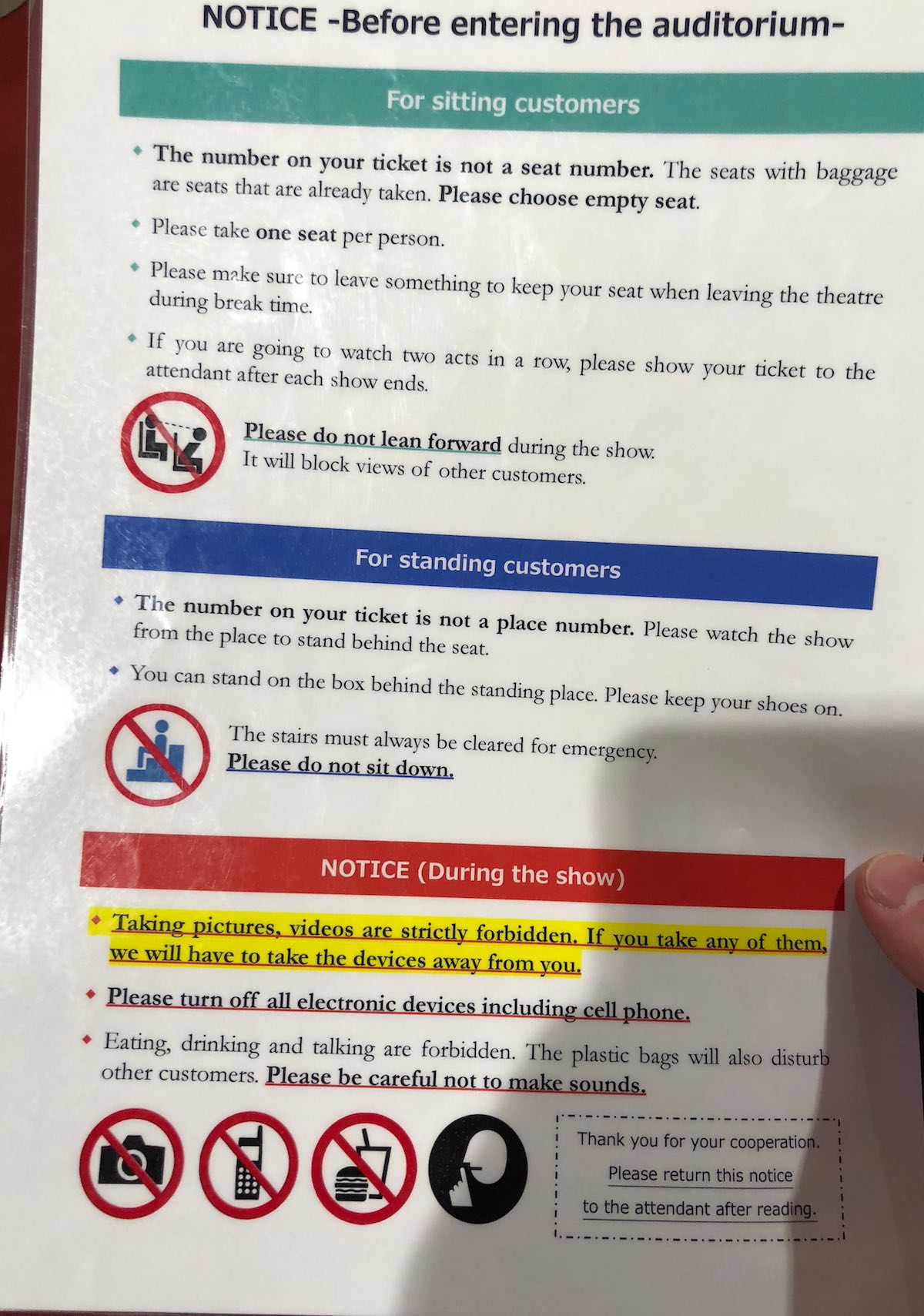

- Kabuki and Bunraku

- Onsen

- Museums

- Festivals (Matsuri)

- Advance Preparation

Introduction

I Love Japan

I love Japan.

There’s so much to see and do in Japan – there’s tons of culture and history to see (not just in Kyoto), the food is both great and varied (not just sushi, although it can be amazing), the cities are interesting and alive (especially in Tokyo and Osaka), the countryside is stunningly beautiful, and the people are extremely nice, friendly, polite and helpful.

There are three secrets about visiting Japan, however:

- It can be a lot cheaper than you expect, especially with the exchange rate on the yen and if you use Hotwire.

- It can be a great family vacation, if your kids are in middle school or high school. Japan is clean and safe–probably cleaner and safer than where you live.

- The JR pass is the best deal ever, but you don’t need it for the days you’re staying in Tokyo.

Now, you can make Japan as expensive as you want. Also, visiting Japan can be a great solo trip, or a great trip with your partner. And you can visit Japan without speaking any Japanese. But those aren’t exactly secrets now, are they?

Every day I’m in Japan I find something new to love about it. I once asked a JR employee if a specific Shinkansen train was for Yamagata or Sendai. He was very polite and helpful, even though I was asking in English. Then I realized, as I was asking, that his shirt said Driver. He was literally a Shinkansen driver. I politely thanked him (in Japanese) for his help, and walked on. About 30 seconds later, long after the interaction had ended, he came running up to me and clarified that the train I was looking at was, in fact, the Shinkansen for Yamagata, not Sendai, and that cars 16 and 17 were the non-reserved cars. He even walked with me a bit toward the end of the train, effectively ensuring I knew which was car 16 before leaving me…

Who is This Book For?

This book is for you if you…

- have never gone to Japan, and

- are considering going to Japan, either solo or with your partner and/or your kids, and you

- either haven’t started or aren’t done planning your trip.

Who is This Book NOT For?

If you haven’t been to Japan, but you’ve already fully planned your trip, booked all your hotels and ordered your exchange orders for your JR passes and read one or more guidebooks, many parts of this book are irrelevant. However, other parts may still be useful.

If you’ve already been to Japan, chances are you’ve learned much or all of what’s in this book already, maybe some of it the hard way. This book is not called Your Second Trip to Japan or A Complete Japan Guidebook, after all. However, you still may get your money’s worth just from the Hotwire tips section.

Finally, while this book is primarily intended for people who are going to Japan for a vacation, parts of it can also be useful for you if you’re going to Japan on business. Obviously the JR pass stuff won’t apply, nor will many of the itinerary suggestions.

What Does This Book Try to Accomplish?

The big idea for this book is this:

Imagine we are both stuck at a party for the next couple hours, with no one else interesting to talk to. You told me that you were considering going to Japan, and I replied that I’d been there twice, spending over 8 weeks in total. You can then use the next couple hours to learn as much as possible from my experience. Everything I would have told you, and more, is in this book. (Also, there are more pictures.)

So, this book tries to be helpful to you, both in preparing for your trip and in the trip itself.

In preparing for your trip, it focuses on the big questions, as it tries to help you…

- Decide whether to go, by reducing the amount of uncertainty. Really, that’s the biggest thing. After you read this book, you should feel a lot more comfortable.

- Plan an itinerary, whether you’re travelling alone, with your partner and/or with your family.

- Pack, whether you’re taking a backpack (preferred) or a suitcase, if you’re travelling in the summer.

- Book hotels, both in the major destinations (Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka) and in the more remote areas.

- Decide whether you need a JR pass, and for how long. (Hint: it might not be for the whole trip.)

- Get a rough idea of costs, so you can decide whether the trip you’re planning fits your budget.

- Get inspired (or get your partner and/or kids inspired) with movies, video games and (gasp!) even other books.

During your trip itself, it tries to help you with some of the basics of daily life, including how to…

- Pay for things. (Hint: usually with cash, and without ever tipping. Really.)

- Get places, taking trains (JR and non-JR), the metro (which you should use in Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka), buses (it’s different than in Canada or the US) and taxis.

- Avoid a number of the basic etiquette mistakes you might make while eating or visiting cultural sites.

- How to communicate effectively enough, even if you don’t speak essentially any Japanese.

- How to pronounce the romanized Japanese (with the same alphabet that is used for English) that you read.

- Get cash from bank machines.

- Do laundry.

This book also contains a very small set of recommendations regarding cheap but tasty food (especially for those travelling with kids), and regarding sights to see.

Frankly, for many people, the Hotwire tips or JR pass tips sections may be worth the price of the book.

What Does This Book NOT Try to Accomplish?

While it’s reasonably straightforward to list what this book is trying to accomplish, it’s impossible to list everything this book is NOT trying to accomplish–there’s just so much that I’m not trying to do.

However, it’s fun to pick some highlights, so that you’re not disappointed when you find them omitted.

This book is NOT trying to be…

- A comprehensive guidebook. The Lonely Planet Japan book is about 1000 pages, and even it omits things. This book is trying to be less than 150, and that’s with a lot of pictures. I want you to be able to read the entire thing in one sitting when you’re planning, and then have it as a reference on your phone when you’re actually in Japan. Your time is limited. Your time to plan your vacation is limited, and your time in Japan will be even more limited.

- Unbiased. Since I’m not trying to be comprehensive, I don’t even have pretend to be unbiased. This book reflects my biases. I hope that they’re helpful for you, regardless of whether you agree or disagree with them, I want to be helpful and transparent about what they are.

- An archaeological, cultural, political, literary, social or religious history of Japan or analysis of present-day Japan. I don’t know enough, and it’s not my place. Occasional references to literature or history will be sprinkled throughout the book, but from the perspective of enhancing your enjoyment of your trip, not to be scholarly.

- A guide to nightlife. I’m highly unqualified: not only am I married, I stopped drinking a couple years ago. Thankfully, in terms of nightlife recommendations, whatever your preferences or orientations are, the Lonely Planet books have a lot of recommendations to offer, as does the internet. Also, if you do drink, cold sake can be tasty, and good Japanese whiskey is amazing, even better than many brands of single malt scotch.

- A guide for parents with children under 8. If you have a limited budget and kids who are under 8, I strongly recommend waiting until they’re older. Seriously. Chances are you’ll only take them to Japan once or twice, and if they’re too young they won’t enjoy much of it or remember any of it–and you’ll possibly just remember how miserable you were.

- A guide for all seasons. The focus is on the summer time, not on spring, fall or winter. There is a simple reason for this: this is probably when you’re going to Japan, and it’s when I’ve been to Japan.

A New Guidebook in 2018?

Of all the things to do in 2018, writing a brand new travel guidebook about Japan seems like a singularly bad idea.

Much of what a travel guidebook does is now partially or entirely obsolete, thanks to the internet and the smartphone. With the combination of iPhone or an Android phone and Google Maps, Google Translate, Trip Advisor, Hotwire and Booking.com, you can now go many places in the world and be totally fine, without even thinking of reading a guidebook.

This list of places definitely includes Japan. You can go to Japan without reading a guidebook or speaking a word of Japanese and have a good enough time.

Furthermore, there are already excellent guidebooks for Japan. Specifically, the Lonely Planet guidebooks, Japan, Tokyo and Kyoto are all first-class. I’ve used all of them in my trips to Japan.

So, why would I write a brand new guidebook about Japan now?

First, I want this guidebook to help you have a great time, not just a good enough time.

Second, this book has a very specific set of skills. It knows what it is and is not trying to be, and it acknowledges its place in the ecosystem. So, it can be a lot smaller and more focused as a result.

Since this book is being created from scratch in 2018, I don’t have to write all the bits which are obsolete, let alone keep them current in future. If information is better found on Google Maps, Trip Advisor or Japan Guide, I don’t have to duplicate it. Instead of pretending those services don’t exist or only offering minimal links, I will embrace them, providing a bunch of clickable links. (These won’t be affiliate links, either: if I link to something it’s because I hope it’s helpful, not because I hope to earn a commission.) This will save you time when you use these services, both to plan in advance, and when you’re looking things up on your phone when you’re actually in Japan.

Also, since I’m publishing the book on Leanpub, I have complete control of it–I don’t have to write something because my publisher says the book needs to be a certain length, or contain things which are traditionally provided.

Next, despite the fact that there are excellent guidebooks for Japan, such as the Lonely Planet ones, the “getting started” information tends to be scattered throughout them, and the absolute basic stuff can be glossed over. So, it’s easy to make a number of avoidable mistakes, involving food, trains, buses, etc.

Another reason is that I’m a co-founder of Leanpub, a publishing startup focused on in-progress publishing. Most of our books are computer programming books, but I think that travel guidebooks are one of the ideal uses for our platform: since they can be easily updated, publishing a new version with one click, an author can keep them current a lot more easily than with other approaches. So, I’m putting my spare time where my opinion is, and writing a travel guidebook myself, in the hope that it inspires a bunch more self-published travel guidebooks on Leanpub.

Obviously, I think there’s a huge opportunity here, not just for travel guidebooks in general, but specifically for this book. I don’t do things hoping they will fail.

Finally, sincere gratitude. I have greatly enjoyed my trips to Japan, both with my family, and when I stayed afterward for some solo adventures. I want to share some of what I’ve learned and enjoyed. Furthermore, the Japanese people have been so nice to me. If this guidebook helps save them from some number of other gaijin making some of the same silly mistakes that I did, this will by my small contribution toward things being more harmonious for them. (However, my wife and I especially feel for the Japanese people with the upcoming Tokyo 2020 Olympics! Sorry in advance on behalf of our fellow Canadians…)

Are You Qualified to Write This Book?

I am not an “expert” on Japan.

First, I’m not Japanese. It’s debatable whether any non-Japanese person can truly “know” Japan. (This is actually a more complex idea than it sounds: since you are a foreigner, less is expected of you. So, even if you moved to Japan and hypothetically learned everything that a Japanese person knew, it would apply differently to you–for better, and for worse.)

Second, I don’t even live in Japan. At the time I’m writing this sentence, I’ve only spent about 8 weeks in Japan, six weeks with my wife and son and two weeks by myself. This was over a three and a half week trip in summer 2016 (when our son was 12), and a five week trip in summer 2018 (when our son was 14).

Third, I don’t even speak Japanese. I muddle by at not much better than “basic tourist” level. I took Japanese 100 in university a long time ago, but I’ve forgotten most of what I had learned.

Fourth, I don’t have a deep understanding of Japanese culture. In university, I took a second year level Japanese Culture class, writing essays comparing the Man’yoshu and Kokinshu and discussing existentialism in the works of Natsume Soseki. But these were all read in translation because, again, I don’t speak Japanese. Similarly, I’ve read Matsuo Basho in translation. I’ve also watched a reasonable amount of Japanese film, especially starring Toshiro Mifune or directed by Akira Kurosawa or ‘Beat’ Takeshi Kitano, but my knowledge of anime and manga is almost nonexistent.

So, compared to the authors of other Japan guidebooks, I am a total beginner when it comes to Japan. And because of this, I’m not qualified to write a traditional guidebook.

However, this is exactly why I am qualified to write this guidebook: there needs to be a guidebook which truly has a “beginner’s mind” about Japan.

If you’re reading this, chances are you also don’t speak Japanese or live in Japan, and chances are you’ve never been to Japan. But you are probably considering visiting Japan, either solo, with your partner, or as a family trip. Well, I’ve been there and done that.

This is where my experiences can help you. Between my trips in 2016 and 2018, I’ve made a number of mistakes, and still had a great time. But many of the mistakes, including situations which were embarrassing or where offense was inadvertently caused, were entirely avoidable. This book can help you learn from my mistakes. More important than simply avoiding mistakes, however, is to learn from the things which went well. I have lots to share there as well.

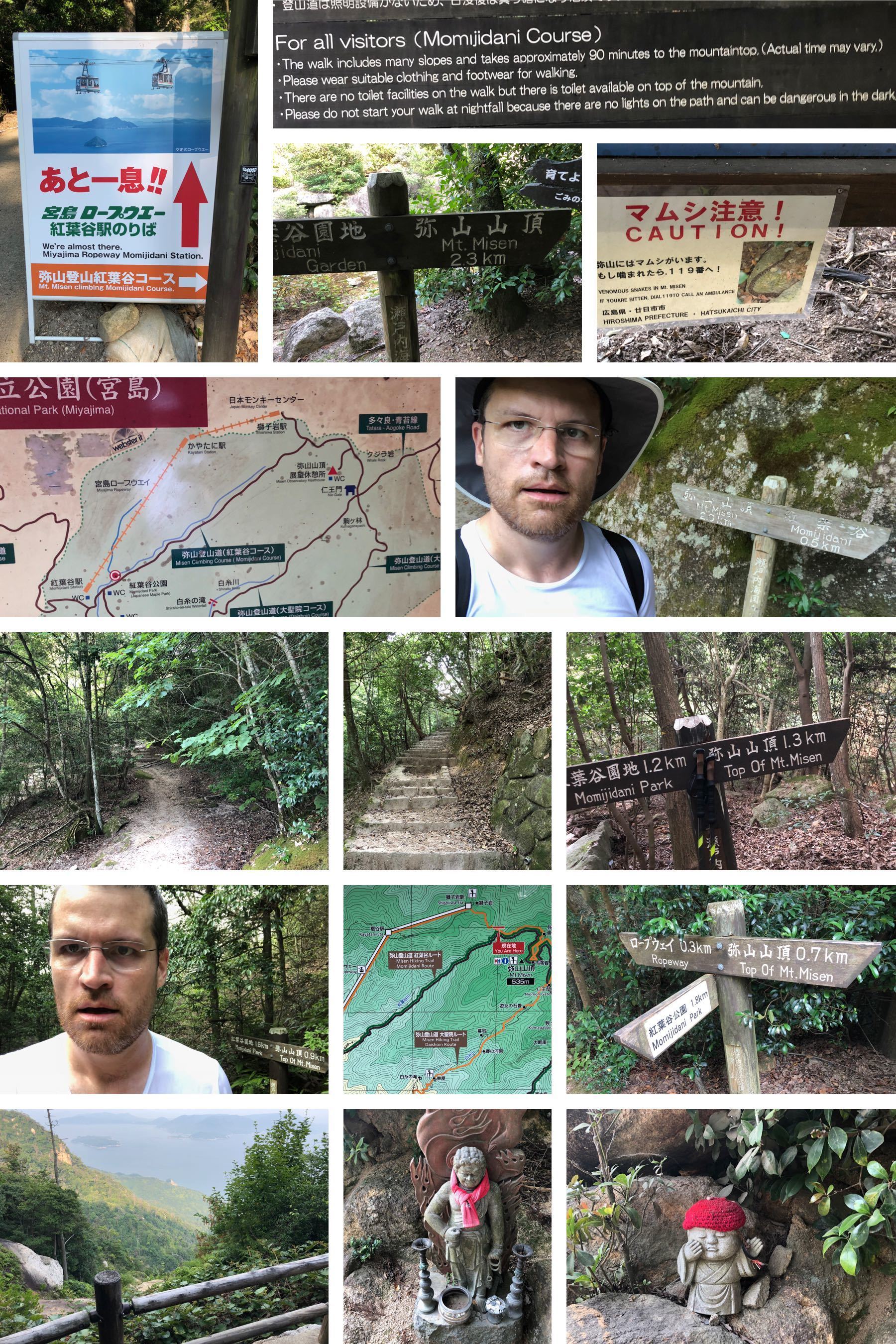

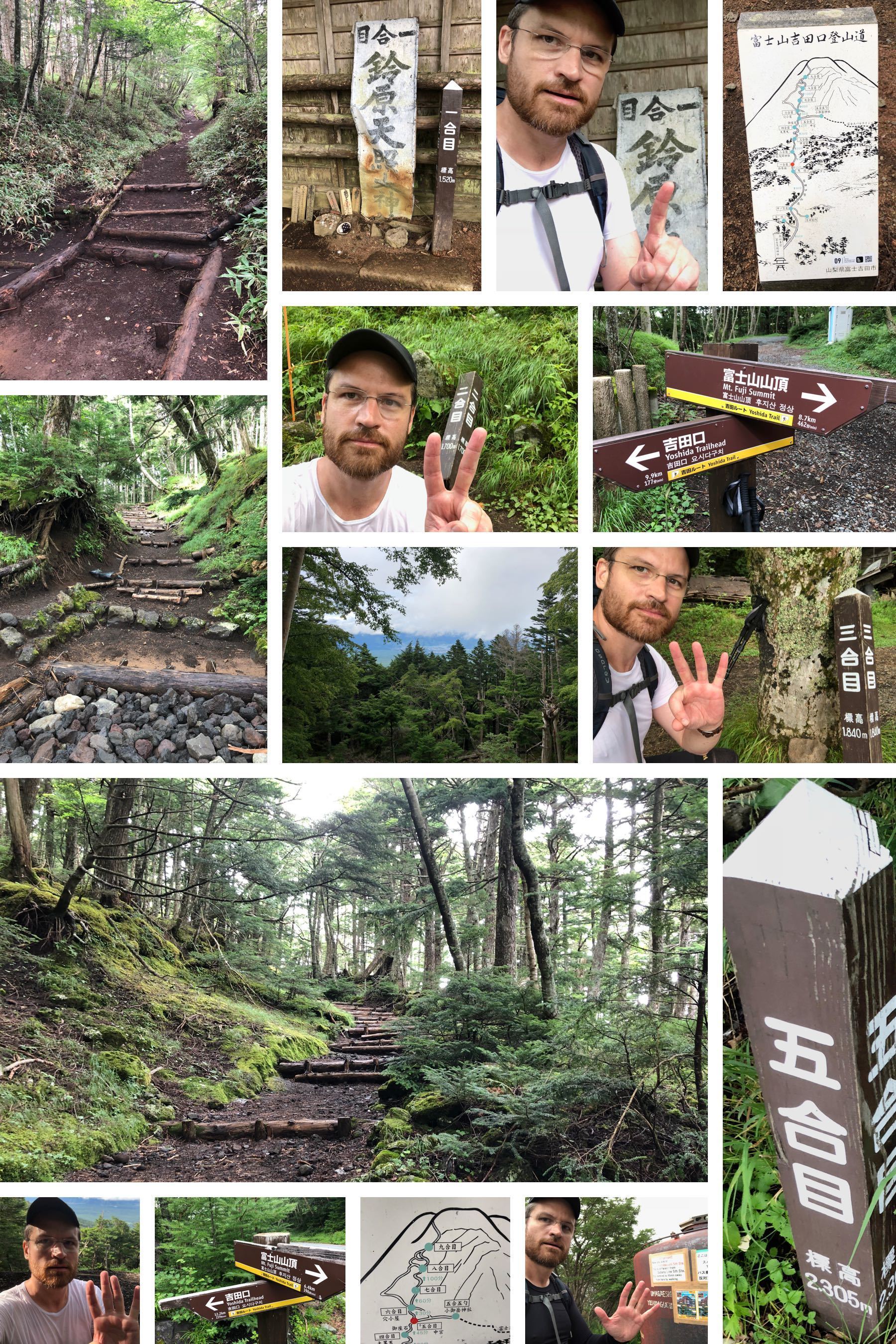

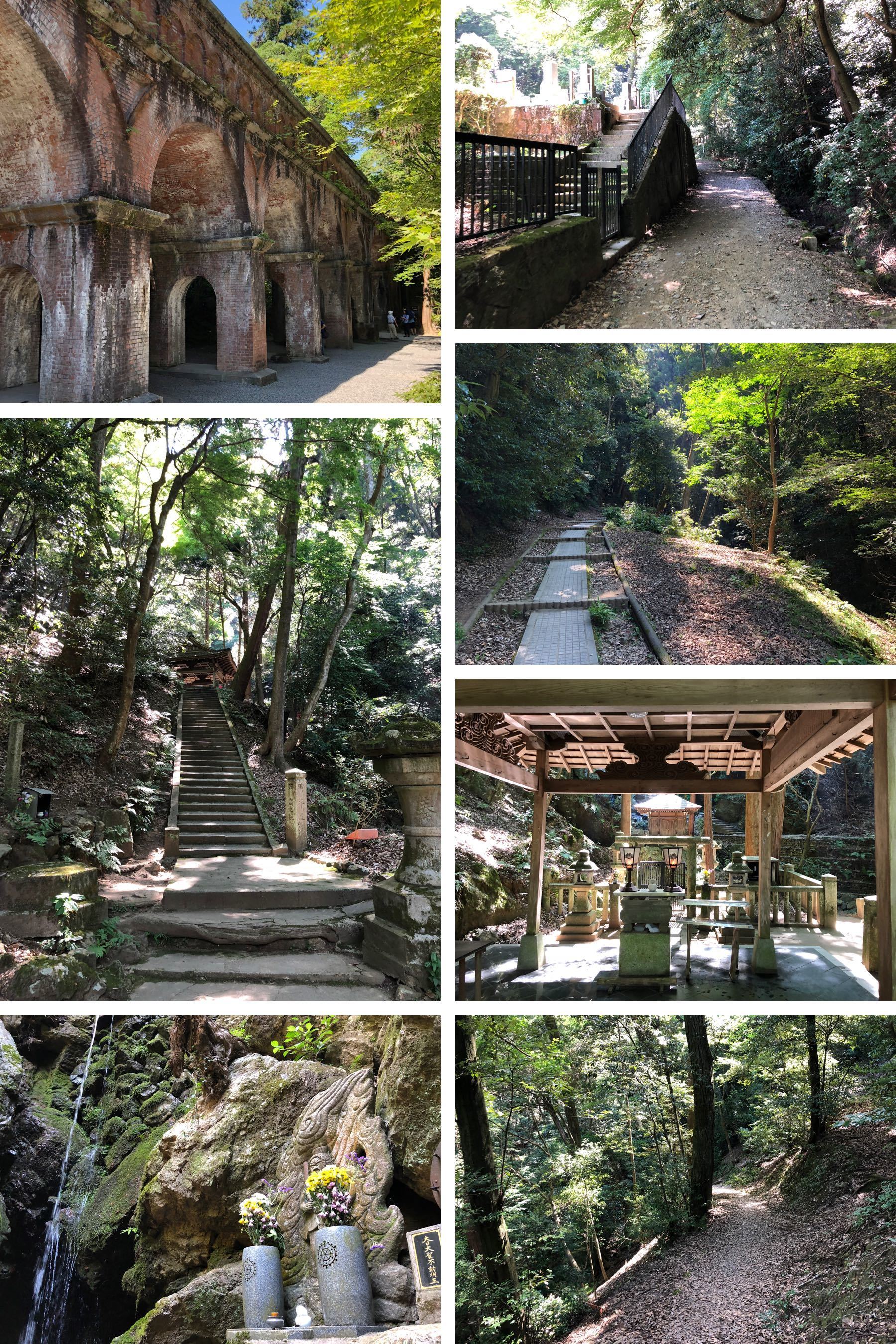

I’ve spent about 3 weeks in Tokyo, over a week in each of Kyoto and Osaka, as well as having visited Himeji, Kochi, Kanazawa, Mount Koya, Miyajima, Matsumoto, Lake Kawaguchi, Nikko, Sendai, Yamadera, Zao Onsen, Tottori, etc. I’ve walked from Magome to Tsumago along the Nakasendo, and I’ve climbed Mount Misen on Miyajima in 37 degree Celsius heat. I’ve also climbed the full Yoshidaguchi trail of Mount Fuji.

My experiences are especially relevant if you are planning a family vacation. My wife and I have taken our son to Japan when he was 12 and 14, so I have lots of experiences to share here.

My goal for this book is to give you advice which significantly improves your trip and saves you more money than the price of the book.

Now, I plan to spend a lot more time in Japan in future. But I’m writing this guidebook now, before I get too good at things, and totally forget what it’s like to be clueless. After I’ve spent a lot more time in Japan I’ll certainly know a lot more, but I may have written a worse book…

This is a Short Book

I’ve written a number of books. Over time, as I’ve gotten older, my books have gotten shorter. My first book, Flexible Rails, was almost 600 pages. My goal is for this book to be under 100 pages, and that will include a number of pictures. The simple reason for this is that it’s a travel book. Not many people have the time or inclination to read a 600 page (or 1000 page!) travel book before their trip, and during your trip you’ll be too busy.

The Photos in the Book

The photos in the book, including that on the cover, were all taken by me, on my iPhone, during my trips in 2018 and 2016. In this book, the pictures are of places, not people (unless they’re selfies)–when I take pictures of people, I try to ask their permission first, but there’s a huge difference between “some tourist took my picture” and “now I’m in an ebook”. So, some of the angles are a bit wonky, or some of the crops are a bit weird, in order to crop out people who would be surprised to find their pictures in this book!

The Prices in the Book

Where relevant, I’ll try to say what something cost, in Japanese yen (JPY). I will sometimes convert this price to what the US dollar (USD) was in 2018. I’m Canadian, but many more people have an intuitive sense of what a US dollar is worth than a Canadian dollar (CAD). In late summer 2018, 1 JPY was about 0.0090 USD, meaning that 1 USD was about 110 JPY.

Sleeping

There are a number of different ways to sleep in Japan. Besides western-style hotels, there are also…

- traditional Japanese inns (Ryokan)

- smaller, family-run establishments (Minshuku), similar to a “Pension” in Europe or a bed & breakfast in North America

- hostels, which can be clean, nice and quiet

- capsule hotels, which is something unique to Japan

There’s also still Airbnb, somewhat. However, this book does not discuss anything to do with Airbnb, due to recent events, and since I have never stayed at an Airbnb in Japan.

Types of Accommodation

Hotels

Hotels are the typical western-style hotels that you’re used to in other countries. In major cities, you can score great deals booking these with Hotwire. In smaller cities, sites like Booking.com or Orbitz work well. See the discussion of Hotwire below.

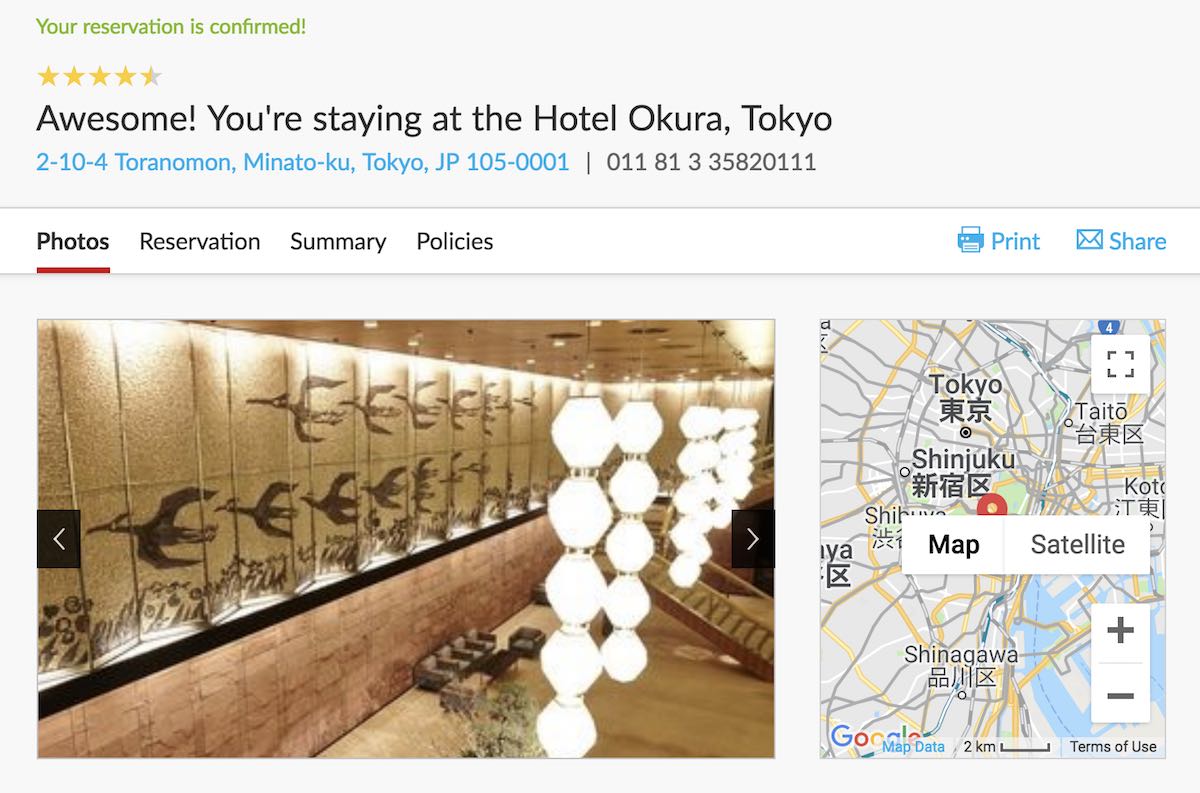

Hotel Okura in Tokyo

Thanks to Hotwire (discussed below), I’ve managed to stay at the Hotel Okura in Tokyo three times, for twelve nights in total. It is amazing, and it would have been way out of my budget without Hotwire.

Even though the Main Wing was demolished in 2015 (they’re building two new enormous wings of it, in preparation for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics) and you are now staying in the South Wing–you feel like a cross between James Bond and Don Draper. (I’ve seen photographs of the old Main Wing, the South Wing is very similar–the South Wing was built in 1973, whereas the Main Wing had been built in 1962, but it seems that some of what was loved about the Main Wing has been moved into the South Wing before the Main Wing was demolished.)

I normally hate swimming pools in general, and hotel swimming pools in particular, but even their swimming pool is fantastic. In terms of their attention to detail: they have two digital thermometers on the wall, the temperature of the air and the temperature of the water. These were kept within one degree each other whenever I was there.

Ryokan

These are traditional Japanese inns. Ryokan often come with dinner and breakfast. Dinner can be simple and delicious in a common dining area, or it can be a fancy kaiseki affair served in your room. I highly recommend that you stay in a ryokan at least once in Japan.

One of the best things about ryokan is that many feature an onsen (a public bath for use by the guests), typically either segmented with one area for male guests and another for female guests, or else done in a way where you and your partner can reserve the onsen for yourselves for, say, a half hour period.

For example, we stayed at the amazing Guesthouse Sakuya in the Lake Kawaguchiko area near Mount Fuji, and we had the onsen to ourselves for half an hour. This is the view of Mount Fuji from the onsen.

Minshuku

These are the similar to a “Pension” in Europe or bed & breakfast in North America. I tried to book a number of these for a planned hike of the Nakahechi route of the Kumano Kodo, but I picked the wrong week (Obon, a week for honouring one’s ancestors, and when many Japanese travel home) to try to do it! Minshuku are smaller than a ryokan and typically don’t feature an onsen, but the hospitality is supposedly really good.

Capsule Hotels

Capsule hotels are a Japanese invention, and they are something that work well in Japan. I’m not sure how well they would work outside Japan.

The pods are stacked two or three high, with a number in a room. You have a sleeping pod for yourself, and a locker in a separate room for your stuff.

I stayed in a capsule hotel fittingly called The Beehive in Tottori. The cost was about 2500 yen (about $23 USD), which is a very good value. (They sold extra things like face masks and ear plugs, but I had my own.) The room I was in had 52 pods in it (the sign on the door said 401-452).

It was actually very clean, quite comfortable and quiet. (I always sleep with earplugs, so this helped.)

There is a screen by your feet, which keeps most of the light out. (I also always sleep with a facemask, so this was totally fine.)

The bathrooms were nice, kind of like what you would find at a nice health club.

Overall, a capsule hotel is fine for a solo one-night stay somewhere, and it’s definitely an experience which is almost unique to Japan.

Hostels

Japan is clean and safe, and that includes hostels. Some have private rooms. My family stayed in a private room in the Thank You Hippopotamus Hostel in Matsumoto, and it was really nice for a hostel. The owner was friendly and helpful, he had produced a hand-drawn map of the town with restaurant recommendations, and there was even laundry to use and air conditioning in the room. (The bathroom was shared, but the door locked.) Also, the location couldn’t be beat: we were basically across the street from Matsumoto castle.

Booking Accommodation

Hotwire: Great for Hotels in Major Cities

In major cities in Japan, Hotwire can be amazing, for two simple reasons:

- Hotwire can save you lots of money. Hotwire has saved my family thousands of dollars in our trips to Japan.

- Hotwire can get you into hotels you would not have afforded otherwise. If it wasn’t for Hotwire, my family would never have stayed in the Hotel Okura in Tokyo.

So, I always look at Hotwire first when booking in a major city in Japan.

One issue with Hotwire is that they often don’t serve smaller cities and towns. However, they do serve Fujikawaguchiko, for example–we booked our stay in Guesthouse Sakuya via Hotwire.

Note, however, that there are a couple of larger issues with Hotwire, which are more of a problem in Japan than, say, Canada or the USA. These are booking with children, and smoking rooms.

Booking With Children

This issue happened when my wife and I used Hotwire to book hotels throughout Japan, both in 2016 and 2018. It’s not an issue with one specific hotel. I don’t think this is so much a problem with Hotwire as a cultural disconnect between Hotwire and Japan.

So, when you book a hotel in Japan on Hotwire for 2 adults and one child, you can often get one queen bed or two double beds. This may have worked when our son was a baby, but it absolutely did not work when our son was 12 or 14–he’s now almost 6 feet tall!

Now, when this happened, the hotels were almost always accommodating, and could typically find a rollaway bed to quickly set up or change the room assignment. However, it was a systemic problem. Maybe by the time you read this it will be fixed, who knows.

However, there’s a simple solution here: if you are booking a room for 2 adults and one child, book it for 3 adults. This way, you will almost always get 3 single beds, or get 2 beds and a rollaway bed already set up. Now, sometimes there’s a cost discrepancy between the 3 adult price and the price for 2 adults and one child, but in that situation, chances are the beds may have been gotten wrong with the 2 adults + one child situation anyway.

If you are travelling as 2 adults and 2 children, you can either search for 4 adults or try your luck with the 2 adults and 2 children combination.

If you are travelling with more than 4 people, such as 2 adults and 3 children, then you need to book 2 rooms: Hotwire only works for a maximum of 4 people in one room.

Smoking Rooms and Non-Smoking Rooms

In Japan, some hotels have smoking rooms and non-smoking rooms. These are segmented by the floor of the hotel.

Now, with Hotwire, they can list non-smoking rooms as an amenity of the hotel. However, just because a hotel has non-smoking rooms does not mean that all its rooms are non-smoking–just that some of them are. When Hotwire books a room, it can often be booked as a smoking room. (At the time of this writing, there is no ability on Hotwire to require that a room be non-smoking.)

In some nicer hotels this is not really an issue, but in some smaller and cheaper hotels this can be terrible. And sometimes, when you show up, the hotel may be completely out of non-smoking rooms for that night. Or, for a longer stay, they may be out of non-smoking rooms for a few nights.

In one situation (not at the Okura), I booked a hotel room for 10 nights, and the hotel only had a non-smoking room for the last 6 nights. Ironically, I had never booked a room for that length of time with Hotwire before, and it was the most smoky Japanese hotel room I had ever been in. I suffered through the first night, and then I just went somewhere else for the next 3 nights, before checking back in to the non-smoking room for the last 6 nights. So, at the end of the day, the cost savings were totally wiped out on that reservation.

So, if you are concerned about this, presumably you can simply phone the hotel later in the day after you make the reservation, to kindly request that your reservation be for a non-smoking room.

Booking.com: Great for Everything

If you can’t find what you want on Hotwire, or if you just want more certainty, Booking.com works great for almost everywhere in Japan. The only time I couldn’t find something suitable on Booking.com were for certain parts of the Kumano Kodo, an ancient pilgrimage route. (However, it turned out that during that week those just weren’t available with any service I tried, so it may be that Booking.com would have worked then as well.)

Besides western-style hotels, I’ve used Booking.com with capsule hotels (e.g. the Beehive in Tottori), hostels (e.g. Thank You Hippopotamus Hostel in Matsumoto) and Ryokan (e.g. Itoya in Zao Onsen).

Orbitz

If, for some reason, you can’t find something suitable on Hotwire or Booking.com, Orbitz also works well in Japan. Also, if you fly a lot, you may have Orbitz’s reward points (“Orbucks”) to use. So, my advice would be to do all your Hotwire bookings first, and then use your Orbucks to book something that you otherwise would have booked on Booking.com. What you don’t want to do is just waste Orbucks on something you could have gotten possibly much cheaper on Hotwire…

Using Rewards Points, like SPG and/or Marriott Points

If you do a lot of business travel, you may have accumulated rewards points with one or more hotel chain. If you’re serious about points, there’s a high probability that this is Marriott and/or SPG. (They’re being combined soon, but it’s not done yet, and I don’t know what the name of the points will be.) Now, until recently, I had a decent amount of Marriott/SPG points. There are both expensive and cheaper places to use these points.

On the luxury end, if you have a ton of points, there are some very nice options in Tokyo where you can possibly get the most bang for your points buck. On the non-luxury end, the Courtyard Shin-Osaka Station is probably the most convenient hotel of them all. Osaka is a great base for day trips as close as Kyoto (12 minutes by Shinkansen), farther away as Himeji and Nara, and even as far as Miyajima and Ise. If you’re planning to do a bunch of day trips from Osaka and have a medium amount of Marriott or SPG points to spend, staying at the Courtyard Shin-Osaka can be a great choice: you literally are attached to the Shin-Osaka station by an overhead walkway.

In terms of how to use rewards points, it kind of varies based on your budget. There are two valid ways to do the math:

- How much dollar value am I getting for my points? (This way is the most fun, and “saves” you the most money.)

- How much am I saving compared to what I actually would have spent? (This way is less fun, but can be the correct way based on your budget at the time.)

Sometimes these result in the same decision, other times they result in different decisions. Both decisions have their merits, and you absolutely shouldn’t go through life only making decision #2!

Time Zones

I live in Victoria, BC, Canada, This means I’m normally on Pacific Time. If you’re also on Pacific Time, jet lag can work in your favour for sightseeing in Japan. When I’m in Japan, I wake up naturally between 5 AM and 6 AM, and it’s like I’ve slept in. So, you can hit the ground running, and see some sights before it gets too hot.

Now, returning back home is tougher, however. I messed it up this most recent time, even though I tried my usual trick of fasting before and during the flight.

Transit

JR Pass

The JR pass is one of the world’s great deals. However, there are two caveats:

- You don’t need it for the days you’re staying in Tokyo. This is discussed later.

- You can’t use it on Nozomi or Mizuho trains. So, you’ll still be riding bullet trains (Shinkansen), but they’ll be the slightly slower ones (e.g. Hikari and Kodama) which make more stops along the way.

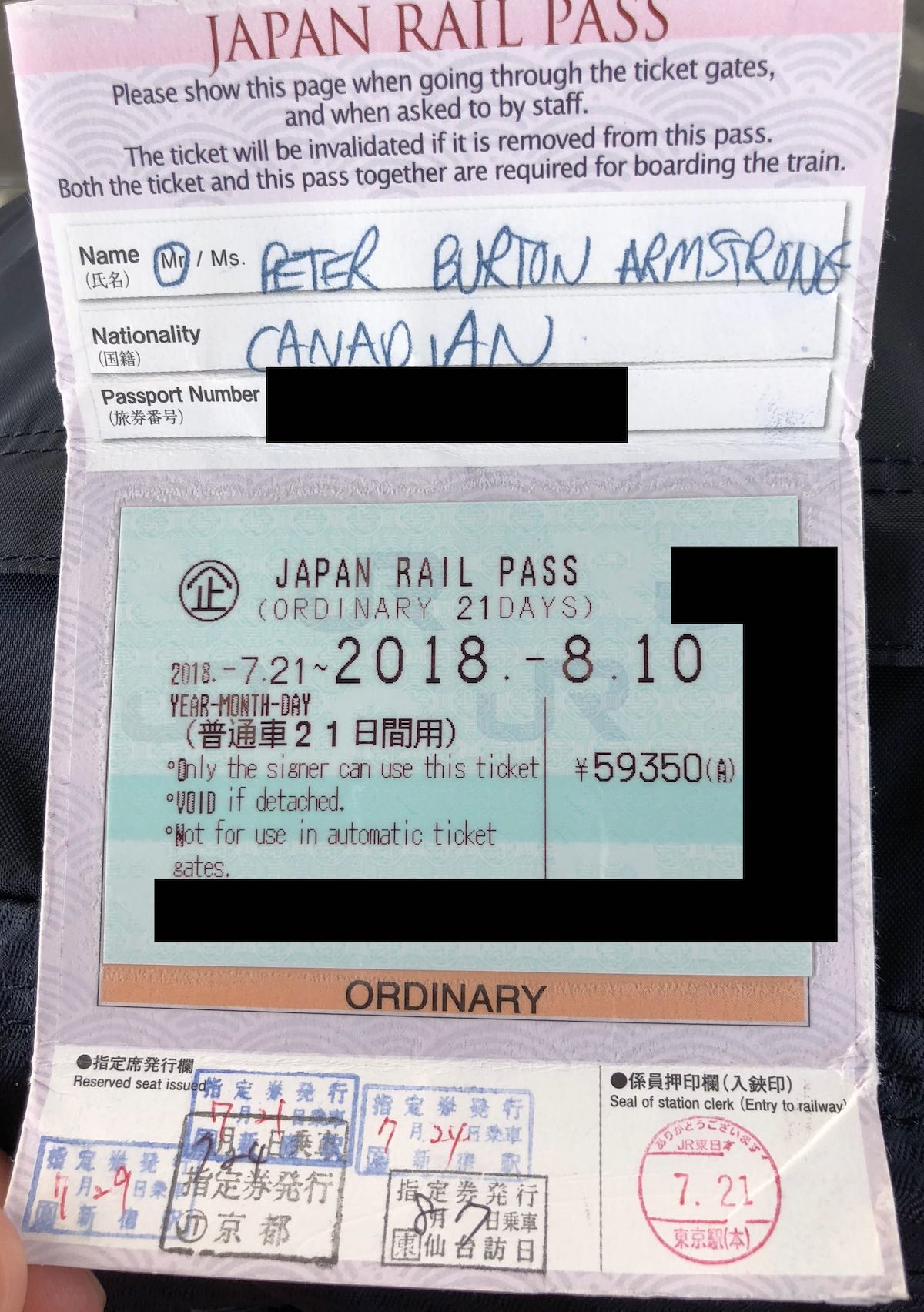

Types of JR Passes

There are actually many different types of JR pass. If you are staying in a reasonably small area, you can possibly save money by buying a regional JR pass. In my trips to Japan, I’ve been traveling for long enough, and in a large enough area, that I just bought the Nationwide JR pass. In fact, the Nationwide JR pass is typically synonymous with “JR pass” for most visitors. Unless you’re planning a very short, very small trip, it’s what you want. So, in this book, when I say “JR pass”, I mean the Nationwide JR pass.

If you are doing any meaningful amount of travel outside of Tokyo, the JR pass is almost certainly for you.

Ordinary vs. Green JR Passes

Finally, there are two types of Nationwide JR pass: Ordinary and Green. The Ordinary gets you access to the ordinary cars; the Green gets you access to the ordinary and green cars.

Neither gets you access to the Nozomi and Mizuho trains. (If there was, I’d pay a few hundred dollars extra for one of those magical passes!)

Anyway, the JR trains are so nice, just save your money and get Ordinary. There’s not that much difference between the cars (I’ve walked through a Green car, just to see), and even the Ordinary cars on many Shinkansen have power outlets. Also, the big reason to just get Ordinary is that booking seats is a hassle, and it’s much simpler and easier to just show up and get a seat in a non-reserved car. But all the non-reserved cars are Ordinary, not Green, so if you use your Green JR pass to sit in an Ordinary car you’re just wasting your money.

Some Trains (e.g. Hayabusa from Tokyo to Hakodate) Are Only Reserved Seats

The JR pass works on all trains except Nozomi or Mizuho trains, and normally you just walk onto a non-reserved train car.

However, there are some trains like the Hayabusa from Tokyo to Hakodate (specifically, to Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto in Hokkaido) which are entirely composed of reserved seats. (That’s a fantastic train, by the way: from Tokyo to Hokkaido in just over 4 hours!)

So, if you have a JR pass and want to go to Hokkaido, make sure you get a Reserved Seat Ticket from a JR ticket office or travel service center. If you know your itinerary, you may want to do this when you convert your exchange order into a JR pass, to save a trip. (If you change your mind about the ticket, make sure you hand in your old ticket when getting a new one, so as to not cost JR a seat.)

How to buy a JR Pass

A JR pass can only be bought before you arrive in Japan. Here’s how you buy a JR pass:

- Buy an exchange order up to 3 months beforehand. You get this from a travel agency on the internet. The one I always use is JTB. I’m Canadian, so the website I used was this one; their US website is here. If for some reason you don’t want to use JTB, there are other choices. Note that you MUST turn in the exchange order within 3 months of ordering it. For example, an Exchange Order which was issued on April 22, 2019 would need to be turned in for a JR pass by July 21, 2019. So, don’t try to order your JR pass 4 or 5 months in advance! (If you do try to order your JR pass, say, 4 months in advance, a good travel agency such as JTB should tell you to wait and try again. However, the better thing to do is just wait until, say, 2 months in advance before ordering your JR pass exchange order.)

- Your exchange order will be sent to you. Do NOT forget to bring it with you to Japan!

- After you arrive in Japan (and have gotten a good sleep and gotten cleaned up), you go to one of the larger JR stations to exchange the exchange order for an actual JR pass. Everyone who is picking up a JR pass will need to show their passport, so if you’re travelling with your family, the act of getting the JR passes will be something you do together. If you’re picking up your JR pass in Tokyo, a good place to do it is the JR Shinjuku station. Not only is there a convenient office there, but you’re also near lots of shopping–including BAKE cheese tarts!

Note that it’s at the point that you exchange your exchange order for your JR pass that you pick the exact days that your JR pass will be valid for. You don’t need to choose this when getting your exchange order. However, whether you’re getting a 1-week, 2-week or 3-week pass, they need to be consecutive. Note that you do NOT need to have your JR pass have its first day be the day you pick it up. You can pick it up on the first day of your trip, but have its first day start, say, a week later. (If you’re going to spend your first week in, say, Tokyo, this is probably the best idea.) A JR pass is smaller to carry around than the exchange order, so you might as well.

Make sure to keep your JR pass safe–if you lose it, it cannot be replaced. It’s a bit big to fit in a normal wallet, but if you have a passport wallet you can fold it a bit and be fine.

Since the days of a JR pass need to be consecutive, and since you’re probably flying to Japan into and out of Tokyo, you’ll want your JR pass to end when you return to Tokyo and fly home. However, when your JR pass starts is a different matter–it could be that the best first day for your JR pass is the last day that you’re in Tokyo, not the first day of your trip.

Using a JR Pass for JR Trains

Obviously, the main things you use a JR pass for is to ride JR trains. This includes all the normal JR trains, and many of the Shinkansen. However, you can’t use the JR pass on two best types of Shinkansen: the Nozomi and Mizuho trains. (Note that I say “JR trains” since there are a number of smaller railway companies in Japan, and the JR pass does not work for them.)

So, when you go to a JR train station, you’ll be choosing a Shinkansen (e.g. Hikari and Kodama) which makes more stops along the way. Or, if you’re going somewhere off the beaten path, you’ll take a normal (non-Shinkansen) train. There are lots of different types of non-Shinkansen trains. Some are still amazingly fast and nice (e.g. the Super Azusa), others are old and slow. Google Maps is your friend here: it will route you on the fastest routes, and suggest the fastest trains to take.

This is usually a good thing, with one enormous caveat.

Dear Google: PLEASE Add a “JR Pass Only” or “Exclude Nozomi and Mizuho” Option to Google Maps

I love Google Maps. It’s essential for a trip to Japan. However, one absolutely infuriating thing about it is that you cannot exclude Nozomi and Mizuho trains.

As you now know, you can’t take them with a JR pass. But Google doesn’t know this. All it knows is that these are the best trains, since they make the fewest stops. So, Google Maps will happily route you on Nozomi and Mizuho trains. Worse, since these routes are so clearly the best routes, Google Maps will often not even show you the Hikari and Kodama trains that you can take, since there is a better Nozomi or Mizuho option.

What to do? Well, there’s a site called HyperDia which lets you choose every possible transport option, and exclude Nozomi and Mizuho trains, etc. It’s amazingly powerful and complex. It’s so complex, in fact, that using it takes a long time.

So, what I actually did was simple: I just assumed that if there was a Nozomi or Mizuho train, there would also be a worse one later, and just went to the train station and figured it out when I got there. (They run a lot of Shinkansen in Japan.)

Dear Google: While You’re At It, Japanese is Not Chinese

Here’s another random Google Maps complaint: when you’re getting directions to somewhere, and that place name is written only in Kanji, Google Maps will often assume it is Chinese, and start speaking the name in Mandarin or Cantonese.

Now, making this 100% accurate is presumably very difficult (since there would be false positives with place names which actually were in Chinese), but right now Google Maps gets it wrong in a lot of situations where it could get it right.

Other Places to use a JR Pass

JR does even operate some ferries, for example the one to Miyajima, and the JR pass does work on those.

Finally, to state the obvious: the JR pass works on the local trains which JR operates. So, if you do have a JR pass, you can find lots of ways to use it, even in the Tokyo area. It’s not just for travelling between cities.

How To Use a JR Pass

Using a JR Pass with Reserved and Non Reserved Seats

There are two ways to use a JR Pass:

- Get (free) reserved tickets for trains. You get your JR pass first, and take it to the ticket office to get tickets. They stamp the bottom of your JR pass when you do this. This is almost always a total waste of time, as there are so many Shinkansen to choose from on a given day. Basically, do this if your partner wants you to, or for the first one or two Shinkansen trips if you don’t feel like a pro yet. (Or, if you want to pick a specific side of the train to sit on–say if you want to try to get a glimpse of Mount Fuji from the Shinkansen–you can get a reserved ticket for this purpose as well.)

- Show up and take non-reserved cars in any train. Every train has non-reserved cars, and you can just show up and almost always find a seat. In a non-reserved car, anyone can sit in any seat. (Even if you can’t find a seat on a train, you can stand.) This is what you should do. The hassle of getting a reserved seat is not worth it. Again, all the non-reserved cars are Ordinary–you don’t have to worry about sitting in a non-reserved Green Car: those don’t exist.

What To Do at the Station

Instead of walking through the turnstiles or using your Suica card (discussed later), what you do is you walk up to the manned booth on one of the sides of the turnstiles. Just show your pass to one of the helpful attendants there, and walk through. Note that some station entrances don’t handle JR passes; you may need to take a short walk. Also, there can sometimes be a small line of a few tourists showing their JR passes and being confused, so it can take a couple minutes to get through here.

If you do not know which train you are catching (because Google Maps is showing you only hours of Nozomi trains, for example), what you can do is ask. For example, in Tokyo Station you can just show your JR pass to the person and say “Osaka?” and they will quickly look at a complex book or sheet and say something like “Platform 22”. The platforms are clearly numbered, so you can just head right there. Or you can go look at a sign board to see the time that your Shinkansen or normal JR train is leaving. You may even have enough time to get some rice triangles and iced coffee.

At the Platform

First, make sure you get to your platform on time–some of the larger train stations can, in fact, be large, and it can take a number of minutes to get through them.

Second, many train platforms have vending machines, and many of the Shinkansen platforms have mini convenience stores in them. So, if you need an iced coffee, water or a rice triangle to keep going, you can get one right on the platform. So, get to your platform a few minutes early.

Finally, every train car has a separate separate line for it. Each car is either reserved or non-reserved. Every Shinkansen has a few cars of non-reserved seating. These are either at the front or the back of the train (not both). Which cars are non-reserved is indicated on the sign for the train. If you have a reserved seat, then line up by your car. If you have a non-reserved seat, go to the group of non-reserved cars and line up at the shortest line. Note that this can take a minute of walking just on the train platform–some of the Shinkansen have 16 cars!

Why You May Not Want a JR Pass for Tokyo

The JR pass is one of the world’s great deals. However, you don’t need it for the days you’re staying in Tokyo.

In Tokyo, there are three main ways to get around on underground and above-ground train tracks:

- The Tokyo Metro

- Toei subway

- JR train lines

If you just use Google Maps on your phone and select the public transit option, it will conveniently route you for the most convenient and fastest way to where you are going.

However, the JR pass only works on JR train lines, not on the Tokyo metro or Toei subway. For those, you need a Suica (or Pasmo) card. (Yes, technically you can buy paper tickets to stick into the machines. Don’t do that. It’s way more convenient to use a Suica card.)

Now, you could mess around and try to find the JR lines instead of the Tokyo Metro or Toei subway, but that’s a waste of time to save not much money.

Furthermore, using a JR pass is a bit awkward at some JR gates in Tokyo–it’s a lot faster to just walk through the turnstiles by swiping your Suica card, just like everyone else.

So, if your Japan itinerary starts with Tokyo, my recommendation is the following: get a JR pass, but have its first day be the day you are leaving Tokyo.

On my first trip to Japan, I got a JR pass which started on my first day in Tokyo. On my second trip to Japan, I got a JR pass which started on my last day in Tokyo.

With almost any advice, there are exceptions, however. If, say, you are planning a 2-week trip to Japan, and you are spending just the first 4 days in Tokyo, then just get a 2-week JR pass and pick it up on the first day. You will still want a Suica card, and you won’t use the JR pass much in Tokyo, but you will still want a 2-week JR pass, since you don’t want to be paying for Shinkansen a-la-carte. So, in that case, you might as well pick up your JR pass on the first day–having one will save you some yen, so you might as well.

Suica (or Pasmo) Card: Get One Immediately

I got a Suica card, and it worked everywhere that took an IC card. (An IC card stands for Integrated Circuit, i.e. it’s a chip card. You use them by tapping, not swiping, just like a credit card with a chip.)

The alternative to Suica is Pasmo. Both work basically everywhere that takes an IC card, but if you’re way out of the major urban centers, Suica might be a bit better for you, so I got one of those. In this book I’ll just say Suica card instead of IC card.

Getting a Suica card is reasonably straightforward.

You can use a Suica card tons of places. It works with the various metros and the various JR and non-JR trains in Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka, of course. It also works with many buses, lockers, vending machines, convenience stores and even taxis. Really. (However, as discussed later, always carry enough cash that you can pay for something with cash!)

(Yes, you can technically use paper tickets with the various metro and train lines, but seriously: don’t do it. The Suica card is so much more convenient than paper tickets, and it’s also supposedly a bit cheaper per ride. With paper tickets you need to figure out how far you are going, and pay accordingly, and this means you lose a few minutes each time you need to buy paper tickets. Even if you’re only going to be in Japan for a week, you seriously need to buy a Suica card.)

Typically you’ll want to load between 5000 and 10,000 yen on it. Since you can pay for so much stuff with it, typically you’ll be reloading it more than you expect.

Treat it like cash, and don’t lose it. Use it for all travel that you can’t pay for with a JR pass.

Everyone In Your Family Needs Their Own Suica

The way you use a Suica card is you tap it at a turnstile in the subway or train station. On each turnstile, there’s a large IC rectangle that you tap your Suica card on. You tap when you enter, and tap again when you exit.

Because of this, every person in your family needs their own Suica card. No, you cannot share and tap twice–this would not work. (Speaking of things that don’t work, if you tap your Suica card to go through a turnstile, and then realize you went to the wrong place, don’t try to tap your Suica card at the same station to get out. This also won’t work, and you’ll need to talk to an attendant to explain what happenend and get let out.)

Google Maps is Essential

Despite the fact that Google Maps does not know how to exclude Nozomi and Mizuho trains, it’s essential. Just choose to start at your current location, say where you want to go, choose transit, and you’re done.

You can also choose to depart at a certain time, which is useful for planning your next day. And if you’re out and about, it’s useful to say that you’re departing sometime in the evening, to see when the last train back from somewhere is. (This can be wrong, however, so check at the station if you’re concerned.)

Google doesn’t get everything exactly right, so you still need to pay attention when travelling. However, it gets most things right. It’s worth it to have an iPhone or Android phone with a data plan in Japan just for Google Maps.

Metro and Trains

Trains and subways are excellent in Japan. However, they are a patchwork of local metro, JR and non-JR trains.

Your Suica card will work on all of these. Your JR pass only works on JR trains.

Sometimes with special trains, like some of the Mount Fuji trains from Otsuki to Mount Fuji station, you will need to purchase an additional ticket as well as swiping your Suica card or showing your JR pass. Also, sometimes on some (non-Shinkansen) trains which you think are entirely JR, there are portions of the route which need a separate ticket. If you get on to the train using a JR pass, you can typically buy this extra ticket on the train from the conductor, so have cash.

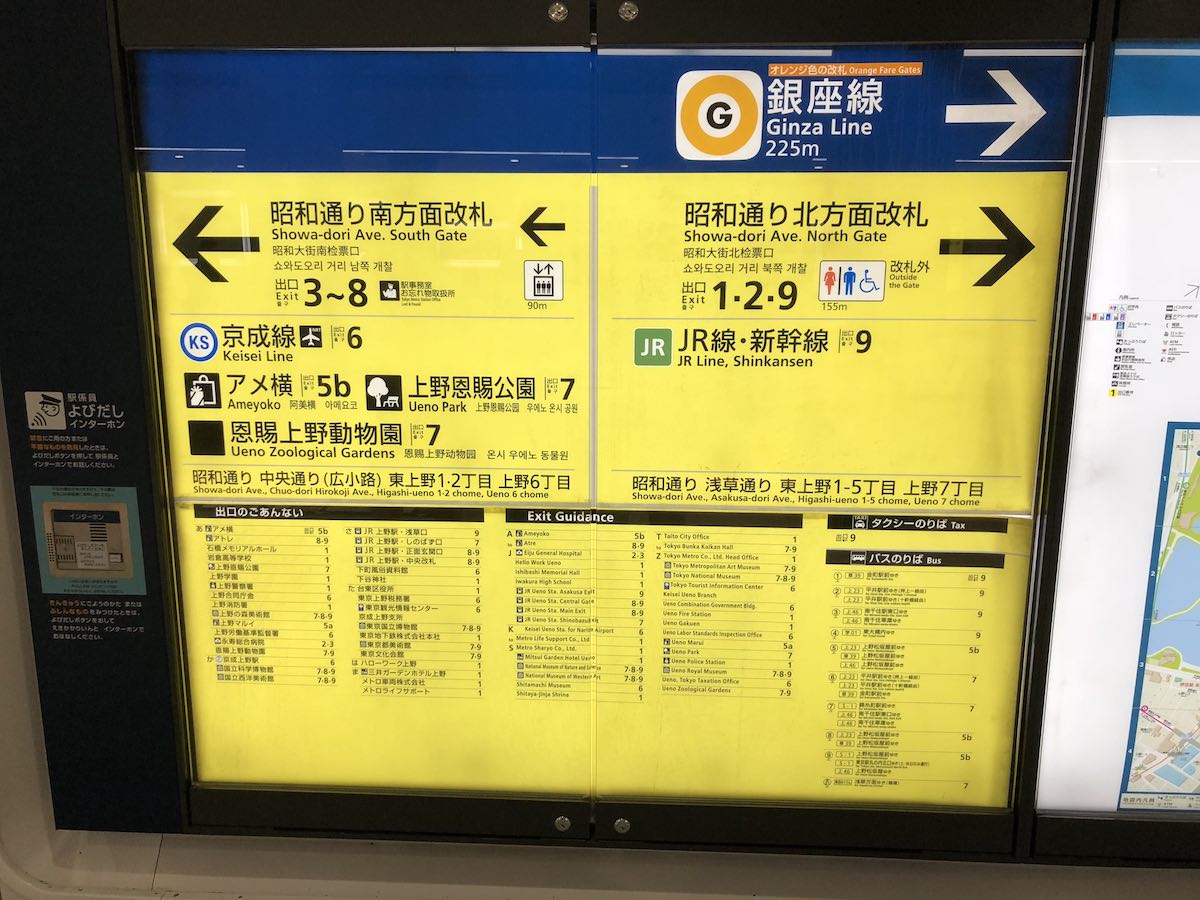

Pay Attention to the Exits

When leaving a subway station or train station, pay attention to the exits–especially in Tokyo. One subway station can have, say, 14 exits. Taking the right one can save 5-15 minutes of walking in the heat outside. Sometimes there are helpful signs, which list a lot of the popular destinations in both Japanese and English, and show the exit you should take. Here’s an example from the Ginza line; note how exits 1, 2 and 9 are in one direction, whereas exits 3-8 are in the other direction:

If you’re often using a subway station near your hotel, you’ll end up remembering which exit it is. Or, if you are concerned, just take a picture of the exit number with your phone when you enter, and look at it when you return.

City Buses

City buses are a good way to get around parts of Kyoto and other smaller cities. Specifically, for Kyoto, many of the temples or shrines you’ll want to see are (deliberately) near the outskirts of Kyoto, presumably so the monks could get some peace and quiet. (City buses do exist in Tokyo and Osaka, but I’ve never taken them there–everything I needed to get to was a short enough walk from a metro or train station.)

City buses, like basically everything else in Japan, are clean and safe. They work exactly backward from in North America, however, as they are based on honesty (the system assumes that people will pay) and intelligence (the system assumes that people will have the cash to do so):

- You get on in the back door, and leave out the front door.

- You pay when you leave, not when you board.

The way this works is when you board, you take a ticket, which has a number on it. The number is for the stop that you boarded. Then, when you leave, you put the ticket in the machine at the front of the bus. It will tell you the fare, and you pay it.

Now, you don’t need to wait until you are leaving to figure out the fare. Instead, as the bus is moving, it shows each stop, and the current price you will pay if you get off at the next stop, having boarded at each stop. These numbers increase as the bus trip continues.

Finally, as with any bus, if you sit above the wheels you have a bumpy ride.

Highway Buses

These can be cheaper than trains, if you don’t have a JR pass. They are also more convenient than trains in certain situations. For example, if you book in advance, the highway bus to and from Mount Fuji can be a good choice; from Shinjuku station to Mount Fuji, it can be cheaper and faster than trains. Go to https://highway-buses.jp/ to book tickets for Mount Fuji from Shinjuku, and arrive early at the train station to find the buses.

I actually took the train from Tokyo to and from Mount Fuji–it was a bit slower (because you need to make a connection to a slower train halfway through the journey) and a tiny bit more expensive, but I enjoy riding on trains more than buses, and I was staying far enough from Shinjuku in Tokyo that the train made sense. Also, I didn’t want to have to book my return ticket, because I wasn’t sure of my itinerary. I did try to get a highway bus back to Tokyo from Mount Fuji, but the tickets were all sold out when I asked at the train station.

Highway buses are typically taken from the train station, but they make other stops. You buy a ticket in advance for them–you don’t just show up and take a number, like a city bus. There are multiple highway bus lines, not just https://highway-buses.jp/; I took some different branded one from Yamagata to Zao Onsen, and I just bought a ticket for it with cash when boarding the bus, since I was getting it at a roadside stop, not at the train station. On the way back, I bought the ticket in advance at the Zao Onsen bus station, using the machine.

Taxis

Taxis can be really expensive. However, for short distances (e.g. in Kyoto) or Osaka they can be not that much worse than transit for a family. Basically, in Tokyo you should take the metro or train everywhere, or walk. But for Kyoto, especially for a family going to a temple or shrine in the heat, a taxi can be a smart exchange of money for time.

For fun, I asked how much it would cost to get a taxi from Mount Fuji’s Fuji Subaru Line 5th Station down to the train station at Lake Kawaguchiko. The answer was over 12,000 yen, or over $100 USD. Thankfully there was excellent highway bus service, for about 10% of that price. That bus ride takes a surprisingly long time, by the way–almost an hour, even though it makes hardly any stops.

How & What to Pack

Take a Backpack, Not a Suitcase or Rollaboard

You should take a backpack, preferably a good one, by Osprey, Deuter or Gregory.

In the absolute worst case, take a rollaboard. Don’t take a larger suitcase.

In our trips to Japan, I took a backpack, and my wife and son both took rollaboard style suitcases. (They’re both as stubborn and opinionated as I am!) Now, for normal business travel, a rollaboard (either the one true version with 2 big wheels, or the 4 wheel spinner version) is obviously a good solution. When travelling, it’s always nicer to never check luggage.

However, for a vacation in Japan, you’re much better off with a smaller backpack, like Osprey’s Farpoint 40 or Fairview 40, than a rollaboard. (Both have been advocated for by women, but the Fairview is the women-specific version of the Farpoint.

There’s a really simple reason why you should take a backpack instead of a rollaboard:

Trains and subways.

Trains and subways are not magical things which you teleport into from your hotel room. Instead, you walk to them. So, while it’s fine to take a rollaboard on a business trip, since you typically take a cab from the airport to and from your hotel, in Japan you really don’t want to be lugging a rollaboard around. Even if you only go to Tokyo, the trains and subways are so good that you will even want to use them to get to and from the airport, regardless of whether you’re flying out of Haneda or Narita. Now, a rollaboard is superior in the airport terminal, but it is decidedly inferior in, say, a 600m or 800m walk from a metro station to your hotel. Pulling a rollaboard over that type of distance can result in a sore shoulder!

Now, if you are actually visiting multiple places in Japan, you will be much better off with a backpack than a rollaboard. Train and subway stations typically have multiple floors, and you will need to get between those floors. There are typically escalators in the larger stations, but not always, especially in the smaller stations. Quite often you will encounter 10-30 stairs. Yes, there will be elevators, but you waste a lot of time having to find them and wait for them. They are typically small and slow, and there are often a lot of tourists with suitcases waiting for them as well. So, you’re stuck either carrying your rollaboard or waiting for an elevator–and in both cases, wishing it was a backpack.

In terms of specific backpacks, I have two Osprey packs, a Farpoint 40 and an Atmos 65. The Farpoint 40 fits in carry-on, and the Atmos 65 does not. However, I took the Atmos 65 on my 2018 trip instead of the Farpoint 40 for three reasons:

- I would have to check my luggage anyway, as I was bringing trekking poles. You can’t bring trekking poles in carry-on luggage.

- I do all the laundry when we travel (I wake up early), and my Atmos 65 would have more room for 3 people’s clothes than my Farpoint 40 would.

- Between my technical clothes for the Mount Fuji hike and the lighter summer clothes for the rest Japan, it was easier to fit everything. The Mount Fuji clothes occupied the entire bottom section of the Atmos 65, so in reality, I was travelling pretty light once you exclude that. (This is especially true since I was going to be in Japan for a month, so I also needed my laptop in order to stay in touch with my team effectively.)

With no laptop and/or no Mount Fuji, it would have been really easy to just bring a Farpoint 40. This would have been especially true if I had packed correctly for the summer season–see the Clothing section later.)

Bring a Daypack

I have a collapsible nylon/polyester backpack from MUJI called the Paraglider Cloth Collapsible Backpack, which serves as a really great daypack. It weighs almost nothing and collapses into a size of a fist when packed, but expands into a 21 liter pack when in use. It’s the perfect daypack–especially if you’re doing things like buying 2L water bottles at 7-11 or Family Mart, and carrying things like an extra shirt (in case you sweat through your first one), hat, sunglasses, etc.

My wife just carried a purse instead of a daypack, since she didn’t want to go full tourist. But when you’re in Japan, and you’re not Japanese, trust me: you look like a tourist. (Or, if you want to look like an expat with an office job, wear dark grey or black dress pants, a white undershirt and a white dress shirt. But that’s a bad idea, since people may speak Japanese to you and expect you to understand it!)

Clothing (Summer Edition)

Summer is hot and humid. I typically dress in “west coast Canadian” (e.g. Lululemon cotton blends), which turns into “stinky sweaty gaijin” in a Japanese summer. Thankfully there are lots of Uniqlo locations in Tokyo, so if you don’t have appropriate clothes or a Uniqlo in your city, just pack very light and go shopping when you get there. (There are also lots of MUJI locations and, of course, a million other stores too.) In Tokyo, you can do all your shopping in Shinjuku or Shibuya. If you’re fancy, you may want to go to Ginza.

In terms of specific recommendations, I will make recommendations which apply to men in the summer:

- Japanese men wear long pants; shorts seem to be for children only. So, if you have a couple pairs of very light, breathable pants, bring those. Now, since you’re a tourist, you can also wear shorts of course. If you don’t have any light, breathable pants, you can buy some at Uniqlo. However, when buying clothes, make sure you try them on.

- It’s hot and humid, so if you are wearing heavy cotton T-shirts, you will sweat through them. So, wear light T-shirts (synthetic or blended) that you expect to sweat in. If everything you own is heavy and gets sweaty, Uniqlo is your best choice: they sell tons of T-shirts, polo shirts and linen shirts. Also, Uniqlo’s Airism brand is particularly suited to the Japanese summer, and is for everything from T-shirts, underwear, athletic wear and dress pants.

- It is warm even in the evening. Unless you are climbing Mount Fuji, you actually don’t need to bring any warm clothing. Imagine you’re packing for Hawaii. (If you are climbing Mount Fuji, then you will be packing two separate sets of clothes: your hot summer clothes, and your Mount Fuji clothes.)

I wouldn’t dream of making clothing recommendations for women, other than to pack light. (Well, I’ll make one: bring a pair of comfortable shoes–you’ll be doing a lot of walking!)

Trekking Poles

If you are going to climb Mount Misen or especially Mount Fuji, you absolutely need trekking poles.

Also, even if you think trekking poles are self-explanatory, you need to watch this video on how to use trekking poles correctly. I watched this video before climbing Mount Fuji, and I realized I had both been holding my poles wrong, and using them wrong.

In Tokyo, there’s a store called L Breath in Shinjuku which has a good selection. I bought an amazing pair of Black Diamond FLZ aluminum poles there. I highly recommend these poles: they worked perfectly for me on Mount Fuji. I chose aluminum poles, since carbon fiber poles can snap, and I absolutely did not want that to happen halfway up Mount Fuji.

Finally, make sure the trekking poles fit your height! I’m 6’3”, and in Japan it’s reasonably difficult to get trekking poles which are long enough. Most of the poles, even in L Breath, were a maximum of 120 cm. These poles went from 120 cm to 140 cm in length, which was perfect for my height: it was very helpful to shorten them to below 125 cm on parts of the ascent, and then to have them above 135 cm on parts of the descent.

Insoles

I swear by my Superfeet blue insoles; my wife and son love their Samurai insoles. You will do a lot of walking in Japan, so premium insoles are worth the money.

Medicine (including Immodium)

Some medicine which is easily available over the counter in North America is hard to find in Japan.

This is especially true of Immodium (loperamide), so bring a supply to save yourself the hassle of trying to find alternatives in case the need arises. My son got some nasty food poisoning on our first trip to Japan (ironically, from Indian food), and it was made far worse by not being able to find suitable medicine. (We were in a fairly remote area, and got some herbal thing which helped a little bit, but he still suffered for a while.)

It’s also difficult to find Polysporin. However, even if you do bring Polysporin, you may wish to pick up some Oronine at a drugstore, since it’s good for a lot of things.

Deodorant

Pack enough deodorant for your entire trip. Japanese deodorant does not work very well, since it is made for Japanese people who don’t stink when they sweat nearly as much as I do when I sweat. I’m serious, by the way–it turns out there are two types of sweat glands, the stinky kind attached to hairs and the not stinky kind, and there are genetic differences here. (I have lots of the stinky kind.)

Power Adapters

Japan has largely 2-prong outlets, and the voltage is 100 volt, not 120 volt like North America.

So, bring an adapter, if you’re bringing anything electrical which is not 2 prong. Also, ensure that it can handle 100 volt power.

If you have a Mac laptop with the power configuration for North America, this is the one time where the 2 prong connector to the power brick will actually be useful, and the 3 prong extension cord will be useless. So, just bring your 2 prong connector, and leave the 3 prong one at home.

If you have an iPhone / iPad / Android phone or tablet, chances are the 2 prong plug will just work and handle the 100 volt power just fine. But in the case of Android, check. I have no idea.

Finally, a note: there are power outlets on the Shinkansen, so if you’re doing a day trip somewhere, consider bringing a power cord for your phone to charge it.

Convenience Stores, Vending Machines & Bank Machines

Convenience Stores

In Japan, the convenience stores are great. The three most prominent ones are 7-11 (aka SEVEN & i HOLDINGS), Family Mart, and Lawson Station (aka Natural Lawson). All three of these typically have cash machines in every branch, which you can use to get cash from your credit card. Now, not every bank machine will work with every credit card; I’ve found the 7-11 bank machines to work best with my credit cards.

Besides getting cash at convenience stores, you can also get quick food at them, especially rice triangles (Onigiri). If you are running around seeing things, getting cash and some rice triangles from 7-11, Family Mart or Lawson Station is a great and quick way to refuel. For me, lots of my walks in Japan have been after my wife, son and I have done some sightseeing and they wanted a break. So, I’d just go to 7-11 or Family Mart and then head out on an adventure.

(Ironically, the train behind me in the photo is a Nozomi, which is one of the kind you can’t take with a JR pass!)

You can also get bottles of iced coffee and water at convenience stores, as well as sparkling water, iced green tea and (non-alcoholic) cider such as Mitsuya Cider.

The price of iced coffee isn’t much different than at a vending machine (typically between 100 and 140 yen for an iced coffee. However, if you want to save money and are wearing a small backpack as a daypack, you can save money on water: at both Family Mart or 7-11, the 2 liter size of water is typically cheaper (about 93 yen) than the 500ml water (about 100 yen). So, if you buy a 2L bottle and carry it around, you’re saving over 300 yen compared to four 500 ml water bottles.

Besides food and beverages and cash, in a pinch you can also buy things like clothes: you’ll often find undershirts and dress shirts at 7-11, Family Mart, and Lawson Station. Sometimes these are house brands, but other times they’re MUJI. However, note that the sizes are very Japanese: I have long arms, and the MUJI XL dress shirts absolutely do not fit my arms.

Getting Cash from Bank Machines

A credit card cash advance is the simplest way of getting cash in Japan. The best bank machines, in terms of accepting your credit card, are at 7-11. Family Mart and Lawson Station can work too, but can be hit & miss.

Take out as much cash as you can at a time. There is a small fee (about 100 to 250 yen) for cash advances at the machine, and your bank may also charge you a surcharge for each credit card cash advance, so you want to minimize the number of transactions. Depending on your daily cash advance limit and what the machine will dispense, this may be something between 40,000 yen and 100,000 yen.

Vending Machines

Vending machines selling cold water, sports drinks, iced coffee and iced green tea are everywhere in Japan.

They take 1000 yen notes, as well as 10, 50, 100 and 500 yen coins. So, they’re great for quenching thirst and getting laundry change. They’re also a great way to get rid of the handful of 10 yen coins you’ll inevitably accumulate.

Iced Coffee

There are a number of brands of iced coffee in Japan. The most prominent is, of course, Suntory BOSS. Now, there are many types of BOSSes.

Like all iced coffee, it’s sweetened unless it says BLACK. My personal go-to was the “PREMIUM BOSS Black”, but it may be an acquired taste–I like my coffee cold and bitter.

If you’re new to vending machine coffee, I recommend trying the BOSS Rainbow Mountain Blend or Wonda Gold. (Wonda is made by Asahi, and anything with ‘Beat’ Takeshi Kitano promoting it has to be good, right?)

There’s also Tully’s (by Keurig) and Georgia Premium (by Coca-Cola), both of which are reasonably good.

Iced Green Tea

You’ll find lots of iced green tea in vending machines and convenience stores. Ito En has good unsweetened green tea, either in the normal or rich (stronger taste) flavour. There’s also a rich green tea by Kirin which is good.

Water

I don’t need to explain water. There are lots of brands of water in Japan, including ones such as Suntory and Asahi which you might associate with beer (Asahi) or whiskey (Suntory). All the flat water tastes good, of course, but the Suntory water (“from the Minami Alps”) is particularly refreshing.

One thing to note is that vending machines typically only sell flat water. So, if you want sparkling water or larger sizes than 500 ml or 600 ml, you’ll need to go to 7-11, Family Mart or Lawson Station.

Sports Drinks

There are a few brands of sports drinks you’ll find throughout Japan, both at vending machines and convenience stores:

- Pocari Sweat - This is similar to Gatorade, but more subtle in taste. (It contains 25 calories per 100 ml, so a 500 ml bottle is 125 calories.)

- Pocari Sweat Ion Water - This is the low-calorie version of Pocari Sweat, which still gives you the electrolytes you need. (It contains 11 calories per 100 ml, so a 500 ml bottle is 55 calories.)

- Aquarius - This is a competitor to Pocari Sweat, made by Coca-Cola.

- Kirin Loves Sports - Breweries like Kirin also make sports drinks.

Pocari Sweat and Ion Water are actually really good, and so is Aquarius. Summer in Japan can get very hot and humid, and heat stroke is a concern. In 2018 we were in Kyoto during a newsworthy heat wave, and temperatures climbed to 38 degrees Celsius for multiple days. During that heat wave especially, it was important for us to drink lots of sports drinks as well as normal water, as well as to use common sense.

Food

There’s lots of delicious food in Japan. Before I get into it, one important tip:

Bring Enough Cash When You Go to a Restaurant

You should assume that all restaurants are cash-only. Many are. You don’t want to be short of cash at a restaurant. My wife and I did this once (we both assumed each other still had enough cash), and after stuffing ourselves with delicious food, I had to sprint around Kanazawa looking for an ATM which worked. (The nearby Lawson Station one did not, but the 7-11 one did.)

Sushi

You can get great sushi in Japan, of course. However, in case you were worried: no, Japanese food isn’t all sushi. In fact, you can travel to Japan and not eat sushi once.

Now, that would be a shame, of course, because sushi can be amazing! You don’t need to go to Tokyo’s Tsukiji market for great sushi. (Frankly, many places in Tsukiji’s outer market are tourist traps in comparison to sushi in other places in Tokyo.)

Sushi Yuu

The best sushi I have ever had, not just in Tokyo but in my entire life, was at a small restaurant called Sushi Yuu, located in a dark backstreet in Roppongi. This isn’t somewhere you take kids: reservations are required, and it’s certainly not cheap. But if you like real sushi, go there and you won’t be disappointed. (You don’t order specific food, you just sit at the counter and trust chef Daisuke (who speaks fluent English) to present you with about ten of the best pieces of sushi of your life, each served in its own artfully-prepared course.)

Ramen

There is amazing ramen all over Japan.

Besides the fact that it’s amazing, ramen is also cheap. A bowl of ramen at Ichiran with no toppings or extras is only 890 yen (about $8 USD), and it might be the best ramen of your life. (With the typical extras, it will cost you about 1500 yen, or $13 USD–still a bargain!)

To get you started, however, I’m going to highlight two of the best ramen chain restaurants in Japan: Ichiran and Ippudo. Both of these chains are Hakata style ramen (Hakata is the alternate name for Fukuoka, on Kyushu). Both of these have locations in Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka. If your itinerary starts as Tokyo ⇒ Kyoto ⇒ Osaka, my advice would be to go to Ichiran in Tokyo and Ippudo in Kyoto. (The Kyoto Ippudo location is right in the train station.) In Osaka, you may be busy eating other things.

Ichiran

Ichiran may or may not make the best tonkotsu ramen in the world, but it’s certainly the best tonkotsu ramen from a chain.

It’s all they do. There are no other types of ramen at Ichiran. Just tonkotsu. There is no other food at Ichiran, either–just tonkotsu ramen, and toppings for it.

Seriously. They don’t even make gyoza. I love gyoza, but this single-minded focus on perfecting one thing is truly laudable.

Since Ichiran is so great, and has locations in Shinjuku, Roppongi and Shinbashi, it should be your first choice for ramen in Tokyo. (However, if you do go to Ichiran, skip the Asakusa location. Ichiran is all about eating ramen at a counter booth, and the Asakusa location has a combination of tables and booths. If you are in a group, as I was with my wife and son in August 2019, chances are you’ll end up at a table. The problem with eating Ichiran at a table is that you’re surrounded by annoying, noisy tourists, and the kaedama extra noodle service takes a lot longer than at a counter booth. Since you need to save some soup for the kaedama, this means you’re eating half a bowl of lukewarm soup.)

Note that tonkotsu is pork broth, so if you’re vegetarian, don’t go to Ichiran. There’s literally no point, since every customer must order tonkotsu ramen.

The way that eating (and it’s definitely eating, not dining) at Ichiran works is unique:

First, you line up. At busy times, the line often spills out the restaurant and up the stairs to the outside.

Next, you buy tickets using cash at a vending machine. Everyone must purchase the “Ramen” ticket, for 890 yen. You then buy other tickets for toppings or for “Kaedama” (extra noodles).

Typically before you get to the vending machine, you will indicate your preferences by circling choices on two pieces of paper. Every person gets their own sheets of paper for preferences, since every person’s preferences are different. There are staff in the line who will give you the paper and help you with this. You indicate how rich you want your broth, how firm you want your noodles, etc. (Pro tip: if you choose different firmness for the Kaedama noodles and the normal noodles, say if you are trying two types of firmness, the staff will just assume you made a mistake and give you the firmness that you chose with the original noodles.)

Make sure to buy all the tickets which correspond to what you selected on page 2 of the preference sheet!

Everyone eats in individual cubicles. This way there’s no talking or socializing, just a single-minded focus on the ramen. (Hey, they have been focusing on perfecting it for decades, they want you to pay attention!) There’s even a tap of cold water in each cubicle.

There is a screen in front of you. It is initially raised, so that you can give your tickets and preference sheet to the staff member. They take it, say some stuff to you (no need to understand or respond), and then they close the screen. A couple minutes later, the screen is raised, and you will get probably the best bowl of ramen you’ve had in your life.

(Note that the red sauce is normally artfully in the center. I started to stir it in, before remembering I needed to actually take a picture of it for once!)

Next, you eat! Slurp your noodles. You need to do this since the soup is piping hot, and you need to start eating right away so the noodles are at the correct firmness. (If you have ordered extra toppings like extra pork or seaweed, it is presented to you on a side plate. Just add it to the bowl of ramen right away, and dig in.)

If you have ordered Kaedama (either a half-order or a full order), make sure to prioritize eating noodles over soup, so that there is enough broth for the Kaedama. When you have about 1/3 of your noodles left, push the button in front of you. A staff member will raise the screen, and take your Kaedama token. About 30 seconds later, you’ll have a plate with your extra noodles, at the correct firmness. (The reason that Kaedama is done this way is that if all the noodles were added to the soup at the beginning, they wouldn’t be at the correct firmness by the end of the bowl.)

Ippudo

Ippudo has both the Hakata Classic tonkotsu ramen and Akamaru Modern miso ramen. Both are good; you should try both to decide which you prefer.

Frankly, if I want classic tonkotsu ramen, I just go to Ichiran. However, Ippudo has one thing that Ichiran does not have–gyoza. If you’ve never had gyoza, they’re the Japanese version of Chinese potsticker pork dumplings.

Ippudo doesn’t just have gyoza, they’re some of the best gyoza I’ve ever had. They’re mini gyoza–about half the size of the gyoza you’re used to, and 10 of them on a plate, instead of the normal 5. They are perfectly cooked–not underdone like some gyoza can be.

The Kyoto location of Ippudo is very convenient–right in the central train station.

Tempura

Many of the foods which are popular throughout Japan are twists on food which originated elsewhere. Just as gyoza are the Japanese take on Chinese potsticker dumplings, tempura originated with a green bean dish imported by Portuguese sailors in the 1500s.

Now, tempura has come a long way since then. You can find it everywhere. It goes particularly well with udon or soba noodle soup, which you can get either hot or cold. I like my udon hot, but cold soba noodles can be delicious on a hot day!

Curry Rice

Another import food which has a unique version in Japan is curry. Curry rice is one of the great fast foods, and you will find Japanese curry places serving cheap pork or beef curry throughout Japan. This is a great alternative to western fast-food chains, and if you are travelling with kids, chances are they will love it.

CoCo Curry

There is a great chain in Japan called CURRY HOUSE CoCo ICHIBANYA. It’s sometimes shortened on signs to CoCoICHI.

What it’s informally called is CoCo Curry. CoCo Curry is actually a really good chain which your kids will probably love. (Frankly, for a quick meal, I love it too: it’s tasty, consistent, basically everywhere, English-friendly and reasonably-priced.)

CoCo Curry has a variety of curries, including their standard pork curry with a chicken cutlet.

All of the curries can have their spice level modified, from three levels of mild all the way up to spice level 10. (However, they won’t let you order above spice level 5 unless you can prove you’ve eaten spice level 5 first.) Now, I have no idea what spice level 5 tastes like–I love spicy food, but even spice level 4 is too spicy for me. I typically eat spice level 2, and sometimes spice level 1 and spice level 3.

You can also get beef curry and other types of curry. And besides a chicken cutlet, you can get calamari, a shrimp cutlet, etc. They also have special curries occasionally. During the summer of 2018 they were celebrating their 40th anniversary with a special curry containing stewed chicken, which was actually pretty good. Here’s a picture of it, with a chicken cutlet added as well:

Now, a pro-tip about CoCo Curry is that you can make it taste even better with a hand-breaded chicken cutlet. This brings CoCo Curry up a quality level, for not that much more money. Just ask for a hand-breaded cutlet instead of a normal one when ordering.

The photo on the next page shows the standard pork curry with a chicken cutlet, the special curry with a chicken cutlet, and the same special curry with a hand-breaded chicken cutlet. I strongly recommend the hand-breaded chicken cutlet, with the special curry if it’s available.

Cheese Tarts

One common sight in train stations in Japan is stores selling cheese tarts. I’m not going to write much about common cheese tarts, however–I’m going to write about the BAKE cheese tart.

BAKE cheese tart

This is by far the best cheese tart I have ever eaten in Japan.

Technically, there are other cheese tart shops in Japan (there are a lot of Pablo locations in Osaka, for example), but in my opinion, you should just go to BAKE. I highly recommend that you do not have a cheese tart anywhere else but BAKE until you have tried theirs. If you do have a cheese tart somewhere else, you may decide that you don’t understand the hype, and you may not try BAKE.